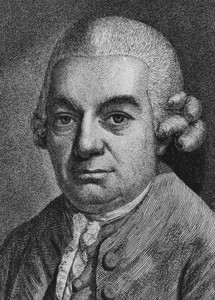

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach) |

Carl Philipp Emmanuel Bach

Of the piano works of Emanuel Bach, I have only a few pieces, and some of them should undoubtedly serve every true artist, not only as an object of high pleasure, but also as material for study. L. Beethoven. Letter to G. Hertel July 26, 1809

Of the entire Bach family, only Carl Philipp Emanuel, the second son of J.S. Bach, and his younger brother Johann Christian achieved the title of “great” during their lifetime. Although history makes its own adjustments to contemporaries’ assessment of the significance of this or that musician, now no one disputes the role of F. E. Bach in the process of the formation of classical forms of instrumental music, which reached its peak in the work of I. Haydn, W. A. Mozart and L. Beethoven. The sons of J.S. Bach were destined to live in a transitional era, when new paths were outlined in music, connected with the search for its inner essence, an independent place among other arts. Many composers from Italy, France, Germany and the Czech Republic were involved in this process, whose efforts prepared the art of the Viennese classics. And in this series of seeking artists, the figure of F. E. Bach stands out especially.

Contemporaries saw the main merit of Philippe Emanuel in the creation of an “expressive” or “sensitive” style of clavier music. The pathos of his Sonata in F minor was subsequently found to be consonant with the artistic atmosphere of Sturm und Drang. The listeners were touched by the exhilaration and elegance of Bach’s sonatas and improvisational fantasies, “talking” melodies, and the author’s expressive manner of playing. The first and only music teacher of Philip Emanuel was his father, who, however, did not consider it necessary to specially prepare his left-handed son, who played only keyboard instruments, for a career as a musician (Johann Sebastian saw a more suitable successor in his first-born, Wilhelm Friedemann). After graduating from the St. Thomas School in Leipzig, Emanuel studied law at the universities of Leipzig and Frankfurt/Oder.

By this time he had already written numerous instrumental compositions, including five sonatas and two clavier concertos. After graduating from the university in 1738, Emanuel devoted himself without hesitation to music and in 1741 received a job as a harpsichordist in Berlin, at the court of Frederick II of Prussia, who had recently ascended the throne. The king was known in Europe as an enlightened monarch; like his younger contemporary, the Russian Empress Catherine II, Friedrich corresponded with Voltaire and patronized the arts.

Shortly after his coronation, an opera house was built in Berlin. However, the entire court musical life was regulated to the smallest detail by the tastes of the king (to the point that during opera performances the king personally followed the performance from the score – over the shoulder of the bandmaster). These tastes were peculiar: the crowned music lover did not tolerate church music and fugue overtures, he preferred the Italian opera to all kinds of music, the flute to all types of instruments, his flute to all flutes (according to Bach, apparently, the true musical affections of the king were not limited to it). ). The well-known flutist I. Kvanz wrote about 300 flute concertos for his august student; every evening during the year, the king in the Sanssouci palace performed all of them (sometimes also his own compositions), without fail in the presence of courtiers. Emanuel’s duty was to accompany the king. This monotonous service was only occasionally interrupted by any incidents. One of them was the visit in 1747 to the Prussian court of J.S. Bach. Being already elderly, he literally shocked the king with his art of clavier and organ improvisation, who canceled his concert on the occasion of the arrival of old Bach. After the death of his father, F. E. Bach carefully kept the manuscripts he inherited.

The creative achievements of Emanuel Bach himself in Berlin are quite impressive. Already in 1742-44. 12 harpsichord sonatas (“Prussian” and “Württemberg”), 2 trios for violins and bass, 3 harpsichord concertos were published; in 1755-65 – 24 sonatas (total approx. 200) and pieces for harpsichord, 19 symphonies, 30 trios, 12 sonatas for harpsichord with orchestra accompaniment, approx. 50 harpsichord concertos, vocal compositions (cantatas, oratorios). The clavier sonatas are of the greatest value – F. E. Bach paid special attention to this genre. The figurative brightness, creative freedom of composition of his sonatas testify to both innovation and the use of musical traditions of the recent past (for example, improvisation is an echo of J. S. Bach’s organ writing). The new thing that Philippe Emanuel introduced to clavier art was a special type of lyrical cantilena melody, close to the artistic principles of sentimentalism. Among the vocal works of the Berlin period, the Magnificat (1749) stands out, akin to the masterpiece of the same name by J. S. Bach and at the same time, in some themes, anticipating the style of W. A. Mozart.

The atmosphere of the court service undoubtedly burdened the “Berlin” Bach (as Philippe Emanuel eventually began to be called). His numerous compositions were not appreciated (the king preferred the less original music of Quantz and the Graun brothers to them). Being respected among the prominent representatives of the intelligentsia of Berlin (including the founder of the Berlin literary and musical club H. G. Krause, musical scientists I. Kirnberger and F. Marpurg, writer and philosopher G. E. Lessing), F. E. Bach in At the same time, he did not find any use for his forces in this city. His only work, which received recognition in those years, was theoretical: “The experience of the true art of playing the clavier” (1753-62). In 1767, F. E. Bach and his family moved to Hamburg and settled there until the end of his life, taking the post of city music director by competition (after the death of H. F. Telemann, his godfather, who had been in this position for a long time). Having become a “Hamburg” Bach, Philippe Emanuel achieved full recognition, such as he lacked in Berlin. He leads the concert life of Hamburg, supervises the performance of his works, in particular choral ones. Glory comes to him. However, the undemanding, provincial tastes of Hamburg upset Philip Emanuel. “Hamburg, once famous for its opera, the first and most famous in Germany, has become musical Boeotia,” writes R. Rolland. “Philippe Emanuel Bach feels lost in it. When Bernie visits him, Philippe Emanuel tells him: “You came here fifty years later than you should have.” This natural feeling of annoyance could not overshadow the last decades of the life of F. E. Bach, who became a world celebrity. In Hamburg, his talent as a composer-lyricist and performer of his own music manifested itself with renewed vigor. “In the pathetic and slow parts, whenever he needed to give expressiveness to a long sound, he managed to extract from his instrument literally cries of sorrow and complaints, which can only be obtained on the clavichord and, probably, only to him alone,” wrote C. Burney . Philip Emanuel admired Haydn, and contemporaries evaluated both masters as equals. In fact, many of the creative discoveries of F. E. Bach were picked up by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven and raised to the highest artistic perfection.

D. Chekhovych