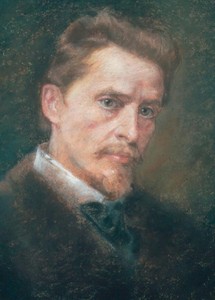

Witold Lutosławski |

Witold Lutosławski

Witold Lutosławski lived a long and eventful creative life; to his advanced years, he retained the highest demands on himself and the ability to update and vary the style of writing, without repeating his own previous discoveries. After the composer’s death, his music continues to be actively performed and recorded, confirming Lutosławski’s reputation as the main – with all due respect to Karol Szymanowski and Krzysztof Penderecki – the Polish national classic after Chopin. Although Lutosławski’s place of residence remained in Warsaw until the end of his days, he was even more than Chopin a cosmopolitan, a citizen of the world.

In the 1930s, Lutosławski studied at the Warsaw Conservatory, where his teacher of composition was a student of N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov, Witold Malishevsky (1873–1939). The Second World War interrupted Lutosławski’s successful pianistic and composing career. During the years of the Nazi occupation of Poland, the musician was forced to limit his public activities to playing the piano in Warsaw cafes, sometimes in a duet with another well-known composer Andrzej Panufnik (1914-1991). This form of music-making owes its appearance to the work, which has become one of the most popular not only in the legacy of Lutoslawsky, but also in the entire world literature for the piano duet – Variations on a Theme of Paganini (the theme for these variations – as well as for many other opuses of various composers “on a theme of Paganini” – was the beginning of the famous 24th caprice of Paganini for solo violin). Three and a half decades later, Lutosławski transcribed the Variations for Piano and Orchestra, a version that is also widely known.

After the end of the Second World War, Eastern Europe came under the protectorate of the Stalinist USSR, and for the composers who found themselves behind the Iron Curtain, a period of isolation from the leading trends in world music began. The most radical reference points for Lutoslawsky and his colleagues were the folklore direction in the work of Bela Bartok and interwar French neoclassicism, the largest representatives of which were Albert Roussel (Lutoslavsky always highly appreciated this composer) and Igor Stravinsky of the period between the Septet for Winds and the Symphony in C major. Even in conditions of lack of freedom, caused by the need to obey the dogmas of socialist realism, the composer managed to create a lot of fresh, original works (Little Suite for chamber orchestra, 1950; Silesian Triptych for soprano and orchestra to folk words, 1951; Bukoliki) for piano, 1952). The pinnacles of Lutosławski’s early style are the First Symphony (1947) and the Concerto for Orchestra (1954). If the symphony tends more towards the neoclassicism of Roussel and Stravinsky (in 1948 it was condemned as “formalist”, and its performance was banned in Poland for several years), then the connection with folk music is clearly expressed in the Concerto: methods of working with folk intonations, vividly reminiscent of Bartók’s style is masterfully applied here to the Polish material. Both scores showed features that were developed in the further work of Lutoslawski: virtuosic orchestration, abundance of contrasts, lack of symmetrical and regular structures (unequal length of phrases, jagged rhythm), the principle of constructing a large form according to the narrative model with a relatively neutral exposition, fascinating twists and turns in unfolding the plot, escalating tension and spectacular denouement.

The Thaw of the mid-1950s provided an opportunity for Eastern European composers to try their hand at modern Western techniques. Lutoslavsky, like many of his colleagues, experienced a short-term fascination with dodecaphony – the fruit of his interest in New Viennese ideas was Bartók’s Funeral Music for string orchestra (1958). The more modest, but also more original “Five Songs on Poems by Kazimera Illakovich” for a female voice and piano (1957; a year later, the author revised this cycle for a female voice with a chamber orchestra) dated from the same period. The music of the songs is notable for the wide use of twelve-tone chords, the color of which is determined by the ratio of intervals that form an integral vertical. Chords of this kind, used not in a dodecaphonic-serial context, but as independent structural units, each of which is endowed with a uniquely original sound quality, will play an important role in all of the composer’s later work.

A new stage in Lutosławski’s evolution began at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s with the Venetian Games for chamber orchestra (this relatively small four-part opus was commissioned by the 1961 Venice Biennale). Here Lutoslavsky first tested a new method of constructing an orchestral texture, in which the various instrumental parts are not fully synchronized. The conductor does not participate in the performance of some sections of the work – he only indicates the moment of the beginning of the section, after which each musician plays his part in free rhythm until the next sign of the conductor. This variety of ensemble aleatorics, which does not affect the form of the composition as a whole, is sometimes called “aleatoric counterpoint” (let me remind you that aleatorics, from Latin alea – “dice, lot”, is commonly referred to as composition methods in which the form or texture of the performed work more or less unpredictable). In most of Lutosławski’s scores, beginning with the Venetian Games, episodes performed in strict rhythm (a battuta, that is, “under the [conductor’s] wand”) alternate with episodes in aleatoric counterpoint (ad libitum – “at will”); at the same time, fragments ad libitum are often associated with static and inertia, giving rise to images of numbness, destruction or chaos, and sections a battuta – with active progressive development.

Although, according to the general compositional conception, Lutoslawsky’s works are very diverse (in each successive score he sought to solve new problems), the predominant place in his mature work was occupied by a two-part compositional scheme, first tested in the String Quartet (1964): the first fragmentary part, smaller in volume, serves a detailed introduction to the second, saturated with purposeful movement, the climax of which is reached shortly before the end of the work. Parts of the String Quartet, in accordance with their dramatic function, are called “Introductory Movement” (“Introductory part”. – English) and “Main Movement” (“Main part”. – English). On a larger scale, the same scheme is implemented in the Second Symphony (1967), where the first movement is entitled “He’sitant” (“Hesitating” – French), and the second – “Direct” (“straight” – French). The “Book for Orchestra” (1968; this “book” consists of three small “chapters” separated from each other by short interludes, and a large, eventful final “chapter”), Cello Concerto are based on modified or complicated versions of the same scheme. with orchestra (1970), Third Symphony (1983). In Lutosławski’s longest-running opus (about 40 minutes), Preludes and Fugue for thirteen solo strings (1972), the function of the introductory section is performed by a chain of eight preludes of various characters, while the function of the main movement is an energetically unfolding fugue. The two-part scheme, varied with inexhaustible ingenuity, became a kind of matrix for Lutosławski’s instrumental “dramas” abounding in various twists and turns. In the mature works of the composer, one cannot find any clear signs of “Polishness”, nor any curtsies towards neo-romanticism or other “neo-styles”; he never resorts to stylistic allusions, let alone directly quoting other people’s music. In a sense, Lutosławski is an isolated figure. Perhaps this is what determines his status as a classic of the XNUMXth century and a principled cosmopolitan: he created his own, absolutely original world, friendly to the listener, but very indirectly connected with tradition and other currents of new music.

The mature harmonic language of Lutoslavsky is deeply individual and is based on filigree work with 12-tone complexes and constructive intervals and consonances isolated from them. Starting with the Cello Concerto, the role of extended, expressive melodic lines in Lutosławski’s music increases, later elements of the grotesque and humor are intensified in it (Novelette for orchestra, 1979; finale of the Double Concerto for oboe, harp and chamber orchestra, 1980; song cycle Songflowers and song tales” for soprano and orchestra, 1990). Lutosławski’s harmonic and melodic writing excludes classical tonal relationships, but allows elements of tonal centralization. Some of Lutosławski’s later major opuses are associated with genre models of Romantic instrumental music; Thus, in the Third Symphony, the most ambitious of all the composer’s orchestral scores, full of drama, rich in contrasts, the principle of a monumental one-movement monothematic composition is originally implemented, and the Piano Concerto (1988) continues the line of brilliant romantic pianism of the “grand style”. Three works under the general title “Chains” also belong to the late period. In “Chain-1” (for 14 instruments, 1983) and “Chain-3” (for orchestra, 1986), the principle of “linking” (partial overlay) of short sections, which differ in texture, timbre and melodic-harmonic characteristics, plays an essential role ( the preludes from the cycle “Preludes and Fugue” are related to each other in a similar way). Less unusual in terms of form is Chain-2 (1985), essentially a four-movement violin concerto (introduction and three movements alternating according to the traditional fast-slow-fast pattern), a rare case when Lutoslawsky abandons his favorite two-part scheme.

A special line in the mature work of the composer is represented by large vocal opuses: “Three Poems by Henri Michaud” for choir and orchestra conducted by different conductors (1963), “Weaved Words” in 4 parts for tenor and chamber orchestra (1965), “Spaces of Sleep ” for baritone and orchestra (1975) and the already mentioned nine-part cycle “Songflowers and Song Tales”. All of them are based on French surrealist verses (the author of the text of “Weaved Words” is Jean-Francois Chabrin, and the last two works are written to the words of Robert Desnos). Lutosławski from his youth had a special sympathy for the French language and French culture, and his artistic worldview was close to the ambiguity and elusiveness of meanings characteristic of surrealism.

Lutoslavsky’s music is notable for its concert brilliance, with an element of virtuosity clearly expressed in it. It is not surprising that outstanding artists willingly collaborated with the composer. Among the first interpreters of his works are Peter Pearce (Woven Words), Lasalle Quartet (String Quartet), Mstislav Rostropovich (Cello Concerto), Heinz and Ursula Holliger (Double Concerto for oboe and harp with chamber orchestra) , Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (“Dream Spaces”), Georg Solti (Third Symphony), Pinchas Zuckermann (Partita for violin and piano, 1984), Anne-Sophie Mutter (“Chain-2” for violin and orchestra), Krystian Zimerman ( Concerto for piano and orchestra) and less known in our latitudes, but absolutely wonderful Norwegian singer Solveig Kringelborn (“Songflowers and Songtales”). Lutosławski himself possessed an uncommon conductor’s gift; his gestures were eminently expressive and functional, but he never sacrificed artistry for the sake of precision. Having limited his conducting repertoire to his own compositions, Lutoslavsky performed and recorded with orchestras from various countries.

Lutosławski’s rich and constantly growing discography is still dominated by original recordings. The most representative of them are collected in double albums recently released by Philips and EMI. The value of the first (“The Essential Lutoslawski”—Philips Duo 464 043), in my opinion, is determined primarily by the Double Concerto and the “Spaces of Sleep” with the participation of the Holliger spouses and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, respectively; the author’s interpretation of the Third Symphony with the Berlin Philharmonic that appears here, oddly enough, does not live up to expectations (the much more successful author’s recording with the British Broadcasting Corporation Symphony Orchestra, as far as I know, was not transferred to CD). The second album “Lutoslawski” (EMI Double Forte 573833-2) contains only proper orchestral works created before the mid-1970s and is more even in quality. The excellent National Orchestra of the Polish Radio from Katowice, engaged in these recordings, later, after the death of the composer, took part in the recording of an almost complete collection of his orchestral works, which has been released since 1995 on discs by the Naxos company (until December 2001, seven discs were released). This collection deserves all the praise. The artistic director of the orchestra, Antoni Wit, conducts in a clear, dynamic manner, and the instrumentalists and singers (mostly Poles) who perform solo parts in concerts and vocal opuses, if inferior to their more eminent predecessors, are very few. Another major company, Sony, released on two discs (SK 66280 and SK 67189) the Second, Third and Fourth (in my opinion, less successful) symphonies, as well as the Piano Concerto, Spaces of Sleep, Songflowers and Songtales “; in this recording, the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra is conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen (the composer himself, who is generally not prone to high epithets, called this conductor “phenomenal”1), the soloists are Paul Crossley (piano), John Shirley-Quirk (baritone), Don Upshaw (soprano)

Returning to the author’s interpretations recorded on CDs of well-known companies, one cannot fail to mention the brilliant recordings of the Cello Concerto (EMI 7 49304-2), the Piano Concerto (Deutsche Grammophon 431 664-2) and the violin concerto “Chain- 2” (Deutsche Grammophon 445 576-2), performed with the participation of the virtuosos to whom these three opuses are dedicated, that is, respectively, Mstislav Rostropovich, Krystian Zimermann and Anne-Sophie Mutter. For fans who are still unfamiliar or little familiar with the work of Lutoslawsky, I would advise you to first turn to these recordings. Despite the modernity of the musical language of all three concertos, they are listened to easily and with special enthusiasm. Lutoslavsky interpreted the genre name “concert” in accordance with its original meaning, that is, as a kind of competition between a soloist and an orchestra, suggesting that the soloist, I would say, sports (in the most noble of all possible senses of the word) valor. Needless to say, Rostropovich, Zimerman and Mutter demonstrate a truly champion level of prowess, which in itself should delight any unbiased listener, even if Lutoslavsky’s music at first seems unusual or alien to him. However, Lutoslavsky, unlike so many contemporary composers, always tried to make sure that the listener in the company of his music would not feel like a stranger. It is worth quoting the following words from a collection of his most interesting conversations with the Moscow musicologist I. I. Nikolskaya: “The ardent desire for closeness with other people through art is constantly present in me. But I do not set myself the goal of winning as many listeners and supporters as possible. I do not want to conquer, but I want to find my listeners, to find those who feel the same way as I do. How can this goal be achieved? I think, only through maximum artistic honesty, sincerity of expression at all levels – from a technical detail to the most secret, intimate depth … Thus, artistic creativity can also perform the function of a “catcher” of human souls, become a cure for one of the most painful ailments – the feeling of loneliness ” .

Levon Hakopyan