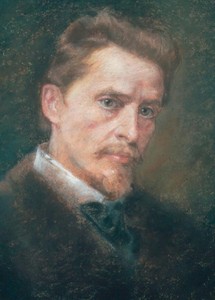

Hugo Wolf |

Contents

Hugo Wolf

In the work of the Austrian composer G. Wolf, the main place is occupied by the song, chamber vocal music. The composer strove for a complete fusion of music with the content of the poetic text, his melodies are sensitive to the meaning and intonation of each individual word, each thought of the poem. In poetry, Wolf, in his own words, found the “true source” of the musical language. “Imagine me as an objective lyricist who can whistle in any manner; to whom both the most hackneyed melody and inspired lyrical tunes are equally accessible, ”said the composer. It is not so easy to understand his language: the composer aspired to be a playwright and saturated his music, which bears little resemblance to ordinary songs, with the intonations of human speech.

Wolf’s path in life and in art was extremely difficult. Years of ascent alternated with the most painful crises, when for several years he could not “squeeze out” a single note. (“It’s truly a dog’s life when you can’t work.”) Most of the songs were written by the composer during three years (1888-91).

The composer’s father was a great lover of music, and at home, in the family circle, they often played music. There was even an orchestra (Hugo played the violin in it), popular music, excerpts from operas sounded. At the age of 10, Wolf entered the gymnasium in Graz, and at 15 he became a student at the Vienna Conservatory. There he became friends with his peer G. Mahler, in the future the largest symphonic composer and conductor. Soon, however, disappointment in the conservatory education set in, and in 1877 Wolff was expelled from the conservatory “due to a violation of discipline” (the situation was complicated by his harsh, direct nature). Years of self-education began: Wolf mastered playing the piano and independently studied musical literature.

Soon he became an ardent supporter of the work of R. Wagner; Wagner’s ideas about the subordination of music to drama, about the unity of word and music were translated by Wolff into the song genre in their own way. The aspiring musician visited his idol when he was in Vienna. For some time, composing music was combined with Wolf’s work as a conductor in the city theater of Salzburg (1881-82). A little longer was the collaboration in the weekly “Viennese Salon Sheet” (1884-87). As a music critic, Wolf defended Wagner’s work and the “art of the future” proclaimed by him (which should unite music, theater and poetry). But the sympathies of the majority of Viennese musicians were on the side of I. Brahms, who wrote music in traditional, familiar to all genres (both Wagner and Brahms had their own special path “to new shores”, supporters of each of these great composers united in 2 warring “camps “). Thanks to all this, Wolf’s position in the musical world of Vienna became rather difficult; his first writings received unfavorable reviews from the press. It got to the point that in 1883, during the performance of Wolff’s symphonic poem Penthesilea (based on the tragedy by G. Kleist), the orchestra members played deliberately dirty, distorting the music. The result of this was the almost complete refusal of the composer to create works for the orchestra – only after 7 years will the “Italian Serenade” (1892) appear.

At the age of 28, Wolf finally finds his genre and his theme. According to Wolf himself, it was as if it “suddenly dawned on him”: he now turned all his strength to composing songs (about 300 in total). And already in 1890-91. recognition comes: concerts are held in various cities of Austria and Germany, in which Wolf himself often accompanies the soloist-singer. In an effort to emphasize the significance of the poetic text, the composer often calls his works not songs, but “poems”: “Poems by E. Merike”, “Poems by I. Eichendorff”, “Poems by J. V. Goethe”. The best works also include two “books of songs”: “Spanish” and “Italian”.

Wolf’s creative process was difficult, intense – he thought about a new work for a long time, which was then entered on paper in finished form. Like F. Schubert or M. Mussorgsky, Wolf could not “divide” between creativity and official duties. Unpretentious in terms of material conditions of existence, the composer lived on occasional income from concerts and the publication of his works. He did not have a permanent angle and even an instrument (he went to friends to play the piano), and only towards the end of his life did he manage to rent a room with a piano. In recent years, Wolf turned to the operatic genre: he wrote the comic opera Corregidor (“can’t we laugh heartily anymore in our time”) and the unfinished musical drama Manuel Venegas (both based on the stories of the Spaniard X. Alarcon) . A severe mental illness prevented him from finishing the second opera; in 1898 the composer was placed in a mental hospital. The tragic fate of Wolf was in many ways typical. Some of its moments (love conflicts, illness and death) are reflected in T. Mann’s novel “Doctor Faustus” – in the life story of the composer Adrian Leverkün.

K. Zenkin

In the music of the XNUMXth century, a large place was occupied by the field of vocal lyrics. The ever-growing interest in the inner life of a person, in the transfer of the finest nuances of his psyche, the “dialectics of the soul” (N. G. Chernyshevsky) caused the flowering of the song and romance genre, which proceeded especially intensively in Austria (starting with Schubert) and Germany (starting with Schumann). ). Artistic manifestations of this genre are diverse. But two streams can be noted in its development: one is associated with the Schubert song tradition, the other – with Schumann declamatory. The first was continued by Johannes Brahms, the second by Hugo Wolf.

The initial creative positions of these two major masters of vocal music, who lived in Vienna at the same time, were different (although Wolf was 27 years younger than Brahms), and the figurative structure and style of their songs and romances were marked by unique individual features. Another difference is also significant: Brahms actively worked in all genres of musical creativity (with the exception of opera), while Wolf expressed himself most clearly in the field of vocal lyrics (he is, in addition, the author of an opera and a small number of instrumental compositions).

The fate of this composer is unusual, marked by cruel life hardships, material deprivation, and need. Having not received a systematic musical education, by the age of twenty-eight he had not yet created anything significant. Suddenly there was artistic maturity; within two years, from 1888 to 1890, Wolf composed about two hundred songs. The intensity of his spiritual burning was truly amazing! But in the 90s, the source of inspiration faded momentarily; then there were long creative pauses – the composer could not write a single musical line. In 1897, at the age of thirty-seven, Wolf was struck by incurable insanity. In the hospital for the insane, he lived another five painful years.

So, only one decade lasted the period of creative maturity of Wolf, and in this decade he composed music in total for only three or four years. However, in this short period he managed to reveal himself so fully and versatile that he was able to rightfully take one of the first places among the authors of foreign vocal lyrics of the second half of the XNUMXth century as a major artist.

* * *

Hugo Wolf was born on March 13, 1860 in the small town of Windischgraz, located in Southern Styria (since 1919, he went to Yugoslavia). His father, a leather master, a passionate lover of music, played the violin, guitar, harp, flute and piano. A large family – among eight children, Hugo was the fourth – lived modestly. Nevertheless, a lot of music was played in the house: Austrian, Italian, Slavic folk tunes sounded (the ancestors of the mother of the future composer were Slovene peasants). Quartet music also flourished: his father sat at the first violin console, and little Hugo at the second console. They also took part in an amateur orchestra, which performed mainly entertaining, everyday music.

From childhood, conflicting personality traits of Wolf appeared: with loved ones he was soft, loving, open, with strangers – gloomy, quick-tempered, quarrelsome. Such character traits made it difficult to communicate with him and, as a result, made his own life very difficult. This was the reason why he was unable to receive a systematic general and professional musical education: only four years Wolf studied at the gymnasium and only two years at the Vienna Conservatory, from which he was fired for “violation of discipline.”

The love of music awakened in him early and was initially encouraged by his father. But he got scared when the young stubborn wanted to become a professional musician. The decision, contrary to his father’s prohibition, matured after a meeting with Richard Wagner in 1875.

Wagner, the famous maestro, visited Vienna, where his operas Tannhäuser and Lohengrin were staged. A fifteen-year-old youth, who had just begun to compose, tried to acquaint him with his first creative experiences. He, without looking at them, nevertheless treated his ardent admirer favorably. Inspired, Wolf gives himself entirely to music, which is as necessary for him as “food and drink.” For the sake of what he loves, he must give up everything, limiting his personal needs to the limit.

Having left the conservatory at the age of seventeen, without paternal support, Wolf lives on odd jobs, receiving pennies for correspondence of notes or private lessons (by that time he had developed into an excellent pianist!). He has no permanent home. (So, from September 1876 to May 1879, Wolf was forced, unable to pay the expenses, to change more than twenty rooms! ..), he does not manage to dine every day, and sometimes he does not even have money for postage stamps to send a letter to his parents. But the musical Vienna, which experienced its artistic heyday in the 70s and 80s, gives the young enthusiast rich incentives for creativity.

He diligently studies the works of the classics, spends many hours in libraries for their scores. To play the piano, he has to go to friends – only by the end of his short life (since 1896) Wolf will be able to rent a room with an instrument for himself.

The circle of friends is small, but they are people sincerely devoted to him. Honoring Wagner, Wolf becomes close to young musicians – students of Anton Bruckner, who, as you know, immensely admired the genius of the author of the “Ring of the Nibelungen” and managed to instill this worship in those around him.

Naturally, with all the passion of his whole nature, joining the supporters of the Wagner cult, Wolf became an opponent of Brahms, and thus the all-powerful in Vienna, the caustically witty Hanslick, as well as other Brahmsians, including the authoritative, widely known in those years, conductor Hans Richter, as well as Hans Bülow.

Thus, even at the dawn of his creative career, irreconcilable and sharp in his judgments, Wolf acquired not only friends, but also enemies.

The hostile attitude towards Wolf from the influential musical circles of Vienna intensified even more after he acted as a critic in the fashionable newspaper Salon Leaf. As the name itself shows, its content was empty, frivolous. But this was indifferent to Wolf – he needed a platform from which, as a fanatical prophet, he could glorify Gluck, Mozart and Beethoven, Berlioz, Wagner and Bruckner, while overthrowing Brahms and all those who took up arms against the Wagnerians. For three years, from 1884 to 1887, Wolf led this unsuccessful struggle, which soon brought him severe trials. But he did not think about the consequences and in his persistent search he sought to discover his creative individuality.

At first, Wolf was attracted to big ideas – an opera, a symphony, a violin concerto, a piano sonata, and chamber-instrumental compositions. Most of them have been preserved in the form of unfinished fragments, revealing the technical immaturity of the author. By the way, he also created choirs and solo songs: in the first he followed mainly everyday samples of the “leadertafel”, while the second he wrote under the strong influence of Schumann.

The most significant works first Wolf’s creative period, which was marked by romanticism, was the symphonic poem Penthesilea (1883-1885, based on the tragedy of the same name by G. Kleist) and The Italian Serenade for string quartet (1887, in 1892 transposed by the author for orchestra).

They seem to embody two sides of the composer’s restless soul: in the poem, in accordance with the literary source telling about the legendary campaign of the Amazons against ancient Troy, dark colors, violent impulses, unbridled temperament dominate, while the music of the “Serenade” is transparent, illuminated by a clear light.

During these years, Wolf was approaching his cherished goal. Despite the need, the attacks of enemies, the scandalous failure of the performance of “Pentesileia” (The Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra in 1885 agreed to show Penthesilea at a closed rehearsal. Prior to that, Wolf was known in Vienna only as a critic of the Salon Leaflet, who embittered both the orchestra members and Hans Richter, who conducted the rehearsal, with his sharp attacks. The conductor, interrupting the performance, addressed the orchestra with the following words: “Gentlemen, we will not play this piece to the end – I just wanted to look at a person who allows himself to write about Maestro Brahms like that …”), he finally found himself as a composer. Begins second – the mature period of his work. With hitherto unprecedented generosity, Wolf’s original talent was revealed. “In the winter of 1888,” he confessed to a friend, “after long wanderings, new horizons appeared before me.” These horizons opened before him in the field of vocal music. Here Wolff is already paving the way for realism.

He tells his mother: “It was the most productive and therefore the happiest year of my life.” For nine months, Wolf created one hundred and ten songs, and it happened that in one day he composed two, even three pieces. Only an artist who devoted himself to creative work with self-forgetfulness could write like that.

This work, however, was not easy for Wolf. Indifferent to the blessings of life, to success and public recognition, but convinced of the rightness of what he did, he said: “I am happy when I write.” When the source of inspiration dried up, Wolf mournfully complained: “How difficult is the fate of the artist if he is unable to say anything new! A thousand times better for him to lie in the grave…”.

From 1888 to 1891, Wolf spoke with exceptional completeness: he completed four large cycles of songs – on the verses of Mörike, Eichendorff, Goethe and the “Spanish Book of Songs” – a total of one hundred and sixty-eight compositions and began the “Italian Book of Songs” (twenty-two works) (In addition, he wrote a number of individual songs based on poems by other poets.).

His name is becoming famous: the “Wagner Society” in Vienna begins to systematically include his compositions in their concerts; publishers print them; Wolf travels with author’s concerts outside of Austria – to Germany; the circle of his friends and admirers is expanding.

Suddenly, the creative spring stopped beating, and hopeless despair seized Wolf. His letters are full of such expressions: “There is no question of composing. God knows how it will end … “. “I have been dead for a long time … I live like a deaf and stupid animal …”. “If I can no longer make music, then you don’t have to take care of me – you should throw me in the trash …”.

There was silence for five years. But in March 1895, Wolf came to life again – in three months he wrote the clavier of the opera Corregidor based on the plot of the famous Spanish writer Pedro d’Alarcon. At the same time he completes the “Italian Book of Songs” (twenty-four more works) and makes sketches of a new opera “Manuel Venegas” (based on the plot of the same d’Alarcon).

Wolf’s dream came true – all his adult life he sought to try his hand at the genre of opera. Vocal works served him as a test in the dramatic kind of music, some of them, by the composer’s own admission, were operatic scenes. Opera and only opera! he exclaimed in a letter to a friend in 1891. “The flattering recognition of me as a song composer upsets me to the depths of my soul. What else can this mean, if not a reproach that I always compose only songs, that I have mastered only a small genre and even imperfectly, since it contains only hints of a dramatic style … “. Such an attraction to the theater permeates the whole life of the composer.

From his youth, Wolf persistently searched for plots for his operatic ideas. But having an outstanding literary taste, brought up on high poetic models, which inspired him when creating vocal compositions, he could not find a libretto that satisfied him. In addition, Wolf wanted to write a comic opera with real people and a specific everyday environment – “without Schopenhauer’s philosophy,” he added, referring to his idol Wagner.

“The true greatness of an artist,” said Wolf, “is found in whether he can enjoy life.” It was this kind of life-juicy, sparkling musical comedy that Wolf dreamed of writing. This task, however, was not entirely successful for him.

For all its particular merits, the music of the Corregidor lacks, on the one hand, lightness, elegance – its score, in the manner of Wagner’s “Meistersingers”, is somewhat heavy, and on the other, it lacks a “big touch”, purposeful dramatic development. In addition, there are many miscalculations in the stretched, insufficiently harmoniously coordinated libretto, and the very plot of d’Alarcon’s short story “The Three-Cornered Hat” (The short story tells how a humpbacked miller and his beautiful wife, passionately loving each other, deceived the old womanizer corregidor (the highest city judge, who, in accordance with his rank, wore a large triangular hat), who sought her reciprocity). The same plot formed the basis of Manuel’s ballet de Falla’s The Three-Cornered Hat (1919).) turned out to be insufficiently weighty for a four-act opera. This made it difficult for Wolf’s only musical and theatrical work to enter the stage, although the premiere of the opera still took place in 1896 in Mannheim. However, the days of the composer’s conscious life were already numbered.

For more than a year, Wolf worked furiously, “like a steam engine.” Suddenly his mind went blank. In September 1897, friends took the composer to the hospital. After a few months, his sanity returned to him for a short time, but his working capacity was no longer restored. A new attack of insanity came in 1898 – this time the treatment did not help: progressive paralysis struck Wolf. He continued to suffer for more than four years and died on February 22, 1903.

M. Druskin

- Wolf’s vocal work →

Compositions:

Songs for voice and piano (total about 275) “Poems of Mörike” (53 songs, 1888) “Poems of Eichendorff” (20 songs, 1880-1888) “Poems of Goethe” (51 songs, 1888-1889) “Spanish Book of Songs” (44 plays, 1888-1889) “Italian Book of Songs” (1st part – 22 songs, 1890-1891; 2nd part – 24 songs, 1896) In addition, individual songs on poems by Goethe, Shakespeare, Byron, Michelangelo and others.

Cantata songs “Christmas Night” for mixed choir and orchestra (1886-1889) The Song of the Elves (to words by Shakespeare) for women’s choir and orchestra (1889-1891) “To the Fatherland” (to the words of Mörike) for male choir and orchestra (1890-1898)

Instrumental works String quartet in d-moll (1879-1884) “Pentesileia”, a symphonic poem based on the tragedy by H. Kleist (1883-1885) “Italian Serenade” for string quartet (1887, arrangement for small orchestra – 1892)

Opera Corregidor, libretto Maireder after d’Alarcón (1895) “Manuel Venegas”, libretto by Gurnes after d’Alarcón (1897, unfinished) Music for the drama “Feast in Solhaug” by G. Ibsen (1890-1891)