Sequence |

Late Lat. sequentia, lit. – what follows following, from lat. sequor – follow

1) Middle-century genre. monody, a hymn sung in the mass after the Alleluia before the reading of the Gospel. Origin of the term “S.” associated with the custom to expand the Alleluia chant, adding to it a jubilant jubilation (jubelus) on the vowels a – e – u – i – a (especially on the last of them). An added jubilee (sequetur jubilatio), originally textless, was subsequently named S. Being an insert (like a vocal “cadenza”), S. is a type of trail. The specificity of S., which distinguishes it from the usual path, is that it is relatively independent. section that performs the function of expanding the previous chant. Developing over the centuries, jubilation-S. acquired various shape. There are two different forms of S.: 1st non-textual (not called S.; conditionally – until the 9th century), 2nd – with text (from the 9th century; actually S.). The appearance of the insert-anniversary refers to approximately the 4th century, the period of the transformation of Christianity into a state. religion (in Byzantium under Emperor Constantine); then the jubilee had a joyfully jubilant character. Here, for the first time, singing (music) acquired an internal. freedom, coming out of subordination to the verbal text (extramusical factor) and rhythm, which was based on dance. or marching. “The one who indulges in jubilation does not utter words: this is the voice of the spirit dissolved in joy…,” Augustine pointed out. Form C. with the text spread to Europe in the 2nd half. 9 in. under the influence of Byzantine (and Bulgarian?) singers (according to A. Gastue, 1911, in hand. C. there are indications: graeca, bulgarica). S., resulting from the substitution of the text for the anniversary. chant, also received the name “prose” (according to one of the versions, the term “prose” comes from the inscription under the title pro sg = pro sequentia, i.e. prose). e. “instead of a sequence”; French pro seprose; however, this explanation does not quite agree with equally frequent expressions: prosa cum sequentia – “prose with a sequent”, prosa ad sequentiam, sequentia cum prosa – here “prose” is interpreted as a text to a sequent). Expansion of jubilee melisma, especially emphasizing melodic. beginning, was called longissima melodia. One of the reasons that caused the substitution of the text for the anniversary was means. difficulty remembering the “longest melody”. Establishing form C. attributed to a monk from the monastery of St. Gallen (in Switzerland, near Lake Constance) Notker Zaika. In the preface to the Book of Hymns (Liber Ymnorum, c. 860-887), Notker himself tells about the history of the S. genre: a monk arrived in St. Gallen from the devastated abbey of Jumiège (on the Seine, near Rouen), who conveyed information about S. to the St. Gallenians. On the advice of his teacher, Iso Notker subtexted the anniversaries according to the syllabic. principle (one syllable per sound of the melody). This was a very important means of clarifying and fixing the “longest melodies”, i.e. because the then dominant method of music. notation was imperfect. Next, Notker proceeded to compose a series of S. “in imitation” of the chants of this kind known to him. Historian. the significance of the Notker method is that the church. musicians and singers for the first time had the opportunity to create a new own. music (Nestler, 1962, p. 63). In the work of Notker, an original music was also developed.

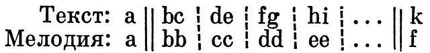

(There could be other variants of the structure of C.)

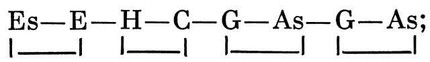

The form was based on double verses (bc, de, fg, …), the lines of which are exactly or approximately equal in length (one note – one syllable), sometimes related in content; pairs of lines are often contrasting. Most notable is the arched connection between all (or almost all) endings of the Muses. lines – either on the same sound, or even close with similar ones. turnovers.

Notker’s text does not rhyme, which is typical of the first period in the development of S. (9th-10th centuries). In Notker’s era, singing was already practiced in chorus, antiphonally (also with alternating voices of boys and men) “in order to visually express the consent of all in love” (Durandus, 13th century). S.’s structure is an important step in the development of music. thinking (see Nestler, 1962, pp. 65-66). Along with the liturgical S. also existed extraliturgical. secular (in Latin; sometimes with instr. accompaniment).

Later S. were divided into 2 types: western (Provence, northern France, England) and eastern (Germany and Italy); among samples

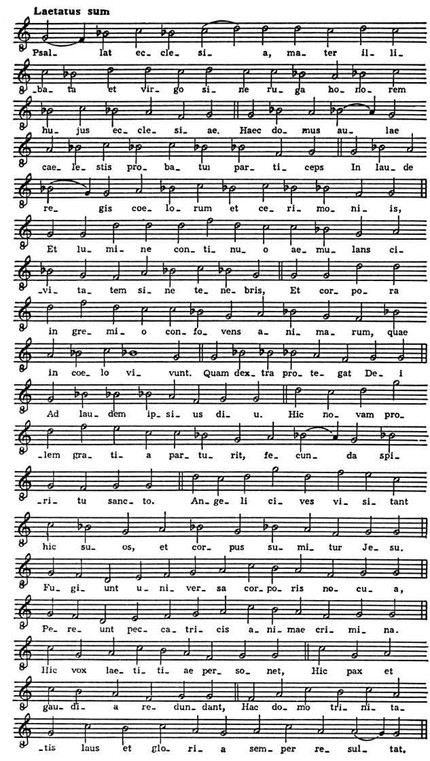

Hotker. Sequence.

initial polyphony is also found in S. (S. Rex coeli domine in Musica enchiriadis, ninth century). S. influenced the development of certain secular genres (estampie, Leich). S.’s text becomes rhymed. The second stage of S.’s evolution began in the 9th century. (the main representative is the author of popular “prose” Adam from the Parisian abbey of Saint-Victor). In form, similar syllables approach a hymn (in addition to syllabics and rhyme, there are meter in verse, periodic structure, and rhyming cadences). However, the melody of the hymn is the same for all stanzas, and in S. it is associated with double stanzas.

The stanza of the anthem usually has 4 lines, and the S. has 3; unlike the anthem, S. is intended for the mass, and not for the officio. The last period of the development of S. (13-14 centuries) was marked by a strong influence of non-liturgical. folk-song genres. Decree of the Council of Trent (1545-63) from the church. services were expelled from almost all S., with the exception of four: Easter S. “Victimae paschali laudes” (text, and possibly the melody – Vipo of Burgundy, 1st half of the 11th century; K. Parrish, J. Ole, p. 12-13, from this melody, probably from the 13th century, the famous chorale “Christus ist erstanden” originates); S. on the feast of the Trinity “Veni sancte spiritus”, which is attributed to S. Langton (d. 1228) or Pope Innocent III; S. for the feast of the Body of the Lord “Lauda Sion Salvatorem” (text by Thomas Aquinas, c. 1263; the melody was originally associated with the text of another S. – “Laudes Crucis attolamus”, attributed to Adam of St. Victor, which was used by P. Hindemith in the opera “Artist Mathis” and in the symphony of the same name); S. early. 13th c. Doomsday Dies irae, ca. 1200? (as part of the Requiem; according to the 1st chapter of the book of the prophet Zephaniah). Later, the fifth S. was admitted, on the feast of the Seven Sorrows of Mary – Stabat Mater, 2nd floor. 13th c. (text authorship unknown: Bonaventure?, Jacopone da Todi?; melody by D. Josiz – D. Jausions, d. 1868 or 1870).

See Notker.

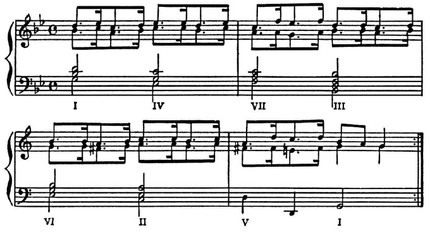

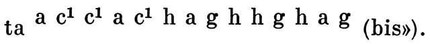

2) In the doctrine of S. harmony (German Sequenze, French marche harmonique, progression, Italian progressione, English sequence) – repetition of melodic. motive or harmonic. turnover at a different height (from a different step, in a different key), following immediately after the first conduction as its immediate continuation. Usually the entire sequence of naz. S., and its parts – links S. The motive of harmonic S. most often consists of two or more. harmonies in simple functions. relationships. The interval by which the initial construction is shifted is called. S. step (the most common shifts are by a second, a third, a fourth down or up, much less often by other intervals; the step can be variable, for example, first by a second, then by a third). Due to the predominance of authentic revolutions in the major-minor tonal system, there is often a descending S. in seconds, the link of which consists of two chords in the lower fifth (authentic) ratio. In such an authentic (according to V. O. Berkov – “golden”) S. uses all degrees of tonality in moving down fifths (up fourths):

G. F. Handel. Suite g-moll for harpsichord. Passacaglia.

S. with an upward movement in fifths (plagal) is rare (see, for example, the 18th variation of Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, bars 7-10: V-II, VI-III in Des-dur). S.’s essence is the linear and melodic movement, in Krom its extreme points have the defining functional value; within the middle links of S., variable functions predominate.

S. are usually classified according to two principles – according to their function in the composition (intratonal – modulating) and according to their belonging to k.-l. from the genera of the sound system (diatonic – chromatic): I. Monotonal (or tonal; also single-system) – diatonic and chromatic (with deviations and secondary dominants, as well as other types of chromatism); II. Modulating (multi-system) – diatonic and chromatic. Single-tone chromatic (with deviations) sequences within a period are often referred to as modulating (according to related keys), which is not true (V. O. Verkov rightly noted that “sequences with deviations are tonal sequences”). Various samples. types of S .: single-tone diatonic – “July” from “The Seasons” by Tchaikovsky (bars 7-10); single-tone chromatic – introduction to the opera “Eugene Onegin” by Tchaikovsky (bars 1-2); modulating diatonic – prelude in d-moll from volume I of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier (bars 2-3); modulating chromatic – development of the I part of Beethoven’s 3rd symphony, bars 178-187: c-cis-d; elaboration of part I of Tchaikovsky’s 4th symphony, bars 201-211: hea, adg. Chromatic modification of authentic sequence is usually the so-called. “dominant chain” (see, for example, Martha’s aria from the fourth act of the opera “The Tsar’s Bride” by Rimsky-Korsakov, number 205, bars 6-8), where the soft gravity is diatonic. secondary dominants are replaced by sharp chromatic ones (“alterative opening tones”; see Tyulin, 1966, p. 160; Sposobin, 1969, p. 23). The dominant chain can go both within one given key (in a period; for example, in the side theme of Tchaikovsky’s fantasy-overture “Romeo and Juliet”), or be modulating (development of the finale of Mozart’s symphony in g-moll, bars 139-47, 126 -32). In addition to the main criteria for S.’s classification, others are also important, for example. S.’s division into melodic. and chordal (in particular, there may be a mismatch between the types of melodic and chord S., going simultaneously, for example, in the C-dur prelude from Shostakovich’s op. chordal – diatonic), into exact and varied.

S. is also used outside the major-minor system. In symmetrical modes, sequential repetition is of particular importance, often becoming a typical form of presentation of the modal structure (for example, single-system S. in the scene of the abduction of Lyudmila from the opera Ruslan and Lyudmila – sounds

in the Stargazer solo from The Golden Cockerel, number 6, bars 2-9 – chords

modulating multi-system S. in the 9th function. Sonata by Scriabin, bars 15-19). In modern S.’s music is enriched with new chords (for example, the polyharmonic modulating S. in the theme of the linking party of the 6st part of the 24th piano of Prokofiev’s sonata, bars 32-XNUMX).

The principle of S. can manifest itself on different scales: in some cases, S. approaches the parallelism of melodic. or harmonic. revolutions, forming micro-C. (e.g., “Gypsy Song” from Bizet’s opera “Carmen” – melodic. S. is combined with the parallelism of accompaniment chords – I-VII-VI-V; Presto in the 1st sonata for solo violin by J. S. Bach, bars 9 -11: I-IV, VII-III, VI-II, V; Intermezzo op. 119 No 1 in h-moll by Brahms, bars 1-3: I-IV, VII-III; Brahms turn into parallelism). In other cases, the principle of S. extends to the repetition of large constructions in different keys at a distance, forming a macro-S. (according to the definition of B.V. Asafiev – “parallel conductions”).

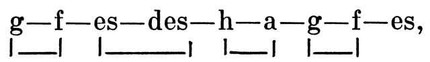

Main composition S.’s purpose is to create the effect of development, especially in developments, connecting parts (in Handel’s g-moll passacaglia, S. is associated with the descending bass g – f – es – d characteristic of the genre; this kind of S. can also be found in other works of this genre).

S. as a way of repeating small compositions. units, apparently, has always existed in music. In one of the Greek treatises (Anonymous Bellermann I, see Najock D., Drei anonyme griechische Trackate über die Musik. Eine kommentierte Neuausgabe des Bellermannschen Anonymus, Göttingen, 1972) melodic. figure with upper auxiliary. sound is stated (obviously, for educational and methodological purposes) in the form of two links S. – h1 – cis2 – h1 cis2 – d2 – cis2 (the same is in Anonymous III, in whom, like S., other melodic. figure – rise “multiple way”). Occasionally, S. is found in the Gregorian chant, for example. in the offertory Populum (V tones), v. 2:

S. is sometimes used in the melody of prof. music of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. As a special form of repetition, sequins are used by the masters of the Parisian school (12th to early 13th centuries); in the three-voice gradual “Benedicta” S. in the technique of voice exchange takes place on the organ point of the sustained lower voice (Yu. Khominsky, 1975, pp. 147-48). With the spread of the canonical technology appeared and canonical. S. (“Patrem” by Bertolino of Padua, bars 183-91; see Khominsky Yu., 1975, pp. 396-397). Principles of strict style polyphony of the 15th-16th centuries. (especially among Palestrina) are rather directed against simple repetitions and S. (and repetition at a different height in this era is primarily imitation); however, S. is still common in Josquin Despres, J. Obrecht, N. Gombert (S. can also be found in Orlando Lasso, Palestrina). In the theoretical S.’s writings are often cited as a way of systematic intervals or to demonstrate the sound of a monophonic (or polyphonic) turnover at different levels according to the ancient “methodical” tradition; see, for example, “Ars cantus mensurabilis” by Franco of Cologne (13th century; Gerbert, Scriptores…, t. 3, p. 14a), “De musica mensurabili positio” by J. de Garlandia (Coussemaker, Scriptores…, t. 1, p. 108), “De cantu mensurabili” of Anonymus III (ibid., pp. 325b, 327a), etc.

S. in a new sense – as the succession of chords (especially descending in fifths) – has become widespread since the 17th century.

References: 1) Kuznetsov K. A., Introduction to the history of music, part 1, M. – Pg., 1923; Livanova T.N., History of Western European music until 1789, M.-L., 1940; Gruber R. I., History of musical culture, vol. 1, part 1. M.-L., 1941; his own, General History of Music, part 1, M., 1956, 1965; Rosenshild K. K., History of foreign music, vol. 1 – Until the middle of the 18th century, M., 1963; Wölf F., Lber die Lais, Sequenzen und Leiche, Heidelberg, 1; Schubiger A., Die Sängerschule St. Gallens von 1841. bis 8. Jahrhundert, Einsiedeln-NY, 12; Ambros AW, Geschichte der Musik, Bd 1858, Breslau, 2; Naumann E., Illustrierte Musikgeschichte, Lfg. 1864, Stuttg., 1 (Russian translation – Hayman Em., An illustrated general history of music, vol. 1880, St. Petersburg, 1); Riemann H., Katechismus der Musikgeschichte, Tl 1897, Lpz., 2 Wagner, P., Einführung in die gregorianische Melodien, (Bd 1888), Freiburg, 2, Bd 1897, Lpz., 1928; Gastouy A., L’art grégorien, P., 1; Besseler H., Die Musik des Mittelalters und der Renaissance, Potsdam, 1895-3; Prunières H., Nouvelle histoire de la musique, pt 1921, P., 1911 Johner D., Wort und Ton im Choral, Lpz., 1931, 34; Steinen W. vd, Notker der Dichter und seine geistige Welt, Bd 1-1934, Bern, 1; Rarrish C, Ohl J., Masterpieces of music before 1937, NY, 1940, L., 1953 The Oxford History of Music, v. 1, L. – Oxf., 2, same, NY, 1948; Chominski JM, Historia harmonii i kontrapunktu, t. 1 Kr., 1750 (Ukrainian translation – Khominsky Y., History of Harmony and Counterpoint, vol. 1951, K., 1952); Nestler G., Geschichte der Musik, Gütersloh, 1975; Gagnepain V., La musigue français du moyen age et de la Renaissance, P., 2: Kohoutek C., Hudebni stylyz hlediska skladatele, Praha, 1932. 1973) Tyulin Yu. H., Teaching about harmony, M. – L. , 1, Moscow, 1958; Sposobin I. V., Lectures on the course of harmony, M., 1; Berkov V. O., Shaping means of harmony, M., 1975. See also lit. under the article Harmony.

Yu. N. Kholopov