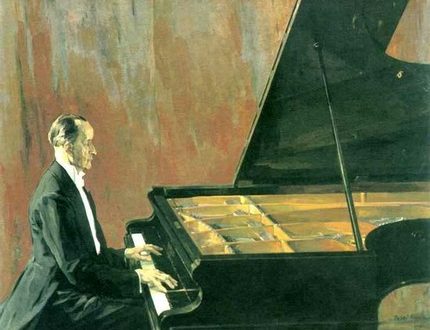

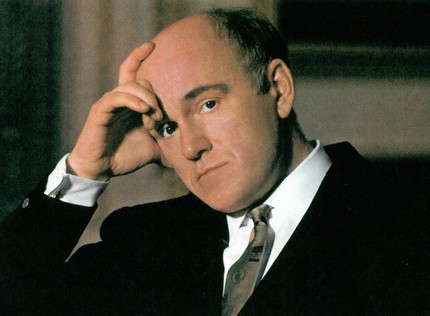

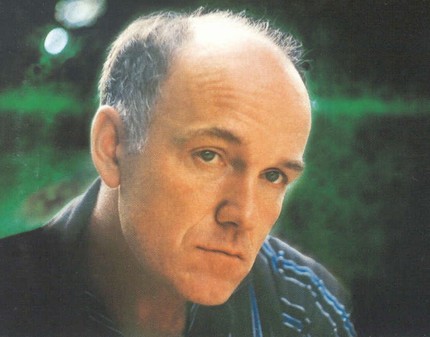

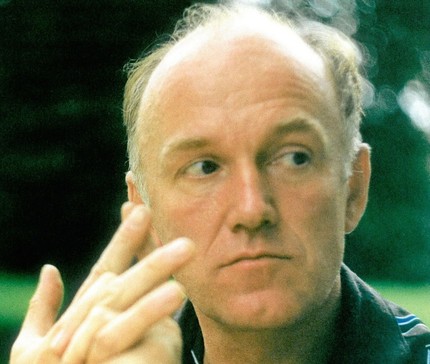

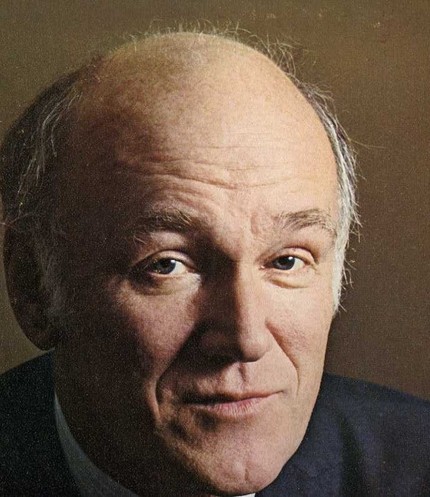

Svyatoslav Teofilovych Richter (Sviatoslav Richter) |

Sviatoslav Richter

Richter’s teacher, Heinrich Gustavovich Neuhaus, once spoke about the first meeting with his future student: “The students asked to listen to a young man from Odessa who would like to enter the conservatory in my class. “Has he already graduated from music school?” I asked. No, he didn’t study anywhere. I confess that this answer was somewhat perplexing. A person who did not receive a musical education was going to the conservatory! .. It was interesting to look at the daredevil. And so he came. A tall, thin young man, fair-haired, blue-eyed, with a lively, surprisingly attractive face. He sat down at the piano, put his big, soft, nervous hands on the keys, and began to play. He played very reservedly, I would say, even emphatically simply and strictly. His performance immediately captured me with some amazing penetration into the music. I whispered to my student, “I think he’s a brilliant musician.” After Beethoven’s Twenty-Eighth Sonata, the young man played several of his compositions, read from a sheet. And everyone present wanted him to play more and more … From that day on, Svyatoslav Richter became my student. (Neigauz G. G. Reflections, memories, diaries // Selected articles. Letters to parents. S. 244-245.).

So, the path in the great art of one of the largest performers of our time, Svyatoslav Teofilovich Richter, began not quite usually. In general, there was a lot of unusual in his artistic biography and there was not much of what is quite usual for most of his colleagues. Before meeting with Neuhaus, there was no everyday, sympathetic pedagogical care, which others feel from childhood. There was no firm hand of a leader and mentor, no systematically organized lessons on the instrument. There were no everyday technical exercises, painstakingly and long study programs, methodical progression from step to step, from class to class. There was a passionate passion for music, a spontaneous, uncontrolled search for a phenomenally gifted self-taught behind the keyboard; there was an endless reading from a sheet of a wide variety of works (mainly opera claviers), persistent attempts to compose; over time – the work of an accompanist at the Odessa Philharmonic, then at the Opera and Ballet Theater. There was a cherished dream of becoming a conductor – and an unexpected breakdown of all plans, a trip to Moscow, to the conservatory, to the Neuhaus.

In November 1940, the first performance of the 25-year-old Richter took place in front of an audience in the capital. It was a triumphant success, specialists and the public started talking about a new, striking phenomenon in pianism. The November debut was followed by more concerts, one more remarkable and more successful than the other. (For example, Richter’s performance of Tchaikovsky’s First Concerto at one of the symphony evenings in the Great Hall of the Conservatory had a great resonance.) The pianist’s fame spread, his fame grew stronger. But unexpectedly, war entered his life, the life of the whole country …

The Moscow Conservatory was evacuated, Neuhaus left. Richter remained in the capital – hungry, half-frozen, depopulated. To all the difficulties that fell to the lot of people in those years, he added his own: there was no permanent shelter, no own tool. (Friends came to the rescue: one of the first should be named an old and devoted admirer of Richter’s talent, artist A. I. Troyanovskaya). And yet it was precisely at this time that he labored at the piano harder, harder than ever before.

In the circles of musicians, it is considered: five-, six-hour exercises daily are an impressive norm. Richter works almost twice as much. Later, he will say that he “really” began to study from the beginning of the forties.

Since July 1942, Richter’s meetings with the general public have resumed. One of Richter’s biographers describes this time as follows: “The life of an artist turns into a continuous stream of performances without rest and respite. Concert after concert. Cities, trains, planes, people… New orchestras and new conductors. And again rehearsals. Concerts. Full halls. Brilliant success…” (Delson V. Svyatoslav Richter. – M., 1961. S. 18.). Surprising, however, is not only the fact that the pianist plays lot; surprised how much brought to the stage by him during this period. Richter’s seasons – if you look back at the initial stages of the stage biography of the artist – a truly inexhaustible, dazzling in its multicolor fireworks of programs. The most difficult pieces of the piano repertoire are mastered by a young musician literally in a matter of days. So, in January 1943, he performed Prokofiev’s Seventh Sonata in an open concert. Most of his colleagues would have taken months to prepare; some of the most gifted and experienced might have done it in weeks. Richter learned Prokofiev’s sonata in… four days.

By the end of the 1945s, Richter was one of the most prominent figures in the splendid galaxy of Soviet pianist masters. Behind him is a victory at the All-Union Competition of Performing Musicians (1950), a brilliant graduation from the conservatory. (A rare case in the practice of a metropolitan musical university: one of his many concerts in the Great Hall of the Conservatory was counted as a state exam for Richter; in this case, the “examiners” were the masses of listeners, whose assessment was expressed with all clarity, certainty and unanimity.) Following the all-Union world fame also comes: since XNUMX, the pianist’s trips abroad began – to Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, and later to Finland, the USA, Canada, England, France, Italy, Japan and other countries. Music criticism peers more and more closely at the artist’s art. There are many attempts to analyze this art, to understand its creative typology, specificity, main features and traits. It would seem that something simpler: the figure of Richter the artist is so large, embossed in outline, original, unlike the others … Nevertheless, the task of “diagnostics” from music criticism turns out to be far from simple.

There are many definitions, judgments, statements, etc., that could be made about Richter as a concert musician; true in themselves, each separately, they – when put together – form, no matter how surprising, a picture devoid of any characteristic. The picture “in general”, approximate, vague, inexpressive. Portrait authenticity (this is Richter, and no one else) cannot be achieved with their help. Let’s take this example: reviewers have repeatedly written about the huge, truly boundless repertoire of the pianist. Indeed, Richter plays almost all piano music, from Bach to Berg and from Haydn to Hindemith. However, is he alone? If we start talking about the breadth and richness of the repertoire funds, then Liszt, and Bülow, and Joseph Hoffmann, and, of course, the great teacher of the latter, Anton Rubinstein, who performed in his famous “Historical Concerts” from above thousand three hundred (!) works belonging to seventy nine authors. It is within the power of some of the modern masters to continue this series. No, the mere fact that on the artist’s posters you can find almost everything intended for the piano does not yet make Richter a Richter, does not determine the purely individual warehouse of his work.

Doesn’t the magnificent, impeccably cut technique of the performer, his exceptionally high professional skill, reveal his secrets? Indeed, a rare publication about Richter does without enthusiastic words about his pianistic skill, complete and unconditional mastery of the instrument, etc. But, if we think objectively, similar heights are also taken by some others. In the age of Horowitz, Gilels, Michelangeli, Gould, it would be generally difficult to single out an absolute leader in piano technique. Or, it was said above about the amazing diligence of Richter, his inexhaustible, breaking all the usual ideas of efficiency. However, even here he is not the only one of his kind, there are people in the music world who can argue with him in this respect as well. (It was said about the young Horowitz that he did not miss the opportunity to practice at the keyboard even at a party.) They say that Richter is almost never satisfied with himself; Sofronitsky, Neuhaus, and Yudina were eternally tormented by creative fluctuations. (And what are the well-known lines – it is impossible to read them without excitement – contained in one of Rachmaninov’s letters: “There is no critic in the world, more in me doubting than myself …”) What then is the key to the “phenotype” (A phenotype (phaino – I am a type) is a combination of all the signs and properties of an individual that have formed in the process of its development.), as a psychologist would say, Richter the artist? In what distinguishes one phenomenon in musical performance from another. In features the spiritual world pianist. In stock it personality. In the emotional and psychological content of his work.

Richter’s art is the art of powerful, gigantic passions. There are quite a few concert players whose playing is pleasing to the ear, pleasing with the graceful sharpness of the drawings, the “pleasantness” of sound colors. Richter’s performance shocks, and even stuns the listener, takes him out of the usual sphere of feelings, excites to the depths of his soul. So, for example, the pianist’s interpretations of Beethoven’s Appassionata or Pathetique, Liszt’s B minor sonata or Transcendental Etudes, Brahms’s Second Piano Concerto or Tchaikovsky’s First, Schubert’s Wanderer or Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition were shocking in their time. , a number of works by Bach, Schumann, Frank, Scriabin, Rachmaninov, Prokofiev, Szymanowski, Bartok… From the regulars of Richter’s concerts one can sometimes hear that they are experiencing a strange, not quite usual state at the pianist’s performances: music, long and well known, is seen as if would be in enlargement, increase, in change of scale. Everything becomes somehow bigger, more monumental, more significant… Andrei Bely once said that people, listening to music, get the opportunity to experience what the giants feel and experience; Richter’s audience is well aware of the sensations that the poet had in mind.

This is how Richter was from a young age, this is how he looked in his heyday. Once, back in 1945, he played at the All-Union competition “Wild Hunt” by Liszt. One of the Moscow musicians who was present at the same time recalls: “… Before us was a titan performer, it seemed, created to embody a powerful romantic fresco. The extreme rapidity of the tempo, flurries of dynamic increases, fiery temperament … I wanted to grab the arm of the chair in order to resist the diabolical onslaught of this music … ” (Adzhemov K. X. Unforgettable. – M., 1972. S. 92.). A few decades later, Richter played in one of the seasons a number of preludes and fugues by Shostakovich, Myaskovsky’s Third Sonata, and Prokofiev’s Eighth. And again, as in the old days, it would have been appropriate to write in a critical report: “I wanted to grab the arm of my chair…” — so strong, furious was the emotional whirlwind that raged in the music of Myaskovsky, Shostakovich, at the end of the Prokofiev cycle.

At the same time, Richter always loved, instantly and completely transformed, to take the listener into the world of quiet, detached sound contemplation, musical “nirvana”, and concentrated thoughts. To that mysterious and hard-to-reach world, where everything purely material in performance — textured covers, fabric, substance, shell — already disappears, dissolves without a trace, giving way only to the strongest, thousand-volt spiritual radiation. Such is the world of Richter’s many preludes and fugues from Bach’s Good Tempered Clavier, Beethoven’s last piano works (above all, the brilliant Arietta from opus 111), the slow parts of Schubert’s sonatas, the philosophical poetics of Brahms, the psychologically refined sound painting of Debussy and Ravel. Interpretations of these works gave grounds to one of the foreign reviewers to write: “Richter is a pianist of amazing inner concentration. Sometimes it seems that the whole process of musical performance takes place in itself. (Delson V. Svyatoslav Richter. – M., 1961. S. 19.). Critic picked up really well-aimed words.

So, the most powerful “fortissimo” of stage experiences and the bewitching “pianissimo” … From time immemorial it has been known that a concert artist, be it a pianist, violinist, conductor, etc., is interesting only insofar as his palette is interesting – wide, rich, diverse – feelings. It seems that the greatness of Richter as a concert performer is not only in the intensity of his emotions, which was especially noticeable in his youth, as well as in the period of the 50s and 60s, but also in their truly Shakespearean contrast, the gigantic scale of the swings: frenzy – profound philosophicality, ecstatic impulse – calm and daydream, active action – intense and complex introspection.

It is curious to note at the same time that there are also such colors in the spectrum of human emotions that Richter, as an artist, has always shunned and avoided. One of the most insightful researchers of his work, Leningrader L. E. Gakkel once asked himself the question: what is in the art of Richter no? (The question, at first glance, is rhetorical and strange, but in fact it is quite legitimate, because absence something sometimes characterizes an artistic personality more vividly than the presence in her appearance of such and such features.) In Richter, Gakkel writes, “… there is no sensual charm, seductiveness; in Richter there is no affection, cunning, play, his rhythm is devoid of capriciousness … ” (Gakkel L. For music and for people // Stories about music and musicians.—L .; M .; 1973. P. 147.). One could continue: Richter is not too inclined to that sincerity, confidential intimacy with which a certain performer opens his soul to the audience – let us recall Cliburn, for example. As an artist, Richter is not one of “open” natures, he does not have excessive sociability (Cortot, Arthur Rubinstein), there is no that special quality – let’s call it confession – which marked the art of Sofronitsky or Yudina. The musician’s feelings are sublime, strict, they contain both seriousness and philosophy; something else – whether cordiality, tenderness, sympathetic warmth … – they sometimes lack. Neuhaus once wrote that he “sometimes, though very rarely” lacked “humanity” in Richter, “despite all the spiritual height of performance” (Neigauz G. Reflections, memories, diaries. S. 109.). It is no coincidence, apparently, that among piano pieces there are also those with which the pianist, due to his individuality, is more difficult than with others. There are authors, the path to which has always been difficult for him; reviewers, for example, have long debated the “Chopin problem” in Richter’s performing arts.

Sometimes people ask: what dominates in the artist’s art – feeling? thought? (On this traditional “touchstone”, as you know, most of the characteristics given to performers by music criticism are tested). Neither one nor the other – and this is also remarkable for Richter in his best stage creations. He was always equally far from both the impulsiveness of romantic artists and the cold-blooded rationality with which “rationalist” performers build their sound constructions. And not only because balance and harmony are in Richter’s nature, in everything that is the work of his hands. Here is something else.

Richter is an artist of a purely modern formation. Like most major masters of the musical culture of the XNUMXth century, his creative thinking is an organic synthesis of the rational and the emotional. Just one essential detail. Not the traditional synthesis of a hot feeling and a sober, balanced thought, as was often the case in the past, but, on the contrary, the unity of a fiery, white-hot artistic thoughts with smart, meaningful feelings. (“Feeling is intellectualized, and thought heats up to such an extent that it becomes a sharp experience” (Mazel L. On the style of Shostakovich // Features of the style of Shostakovich. – M., 1962. P. 15.)– these words of L. Mazel, defining one of the important aspects of the modern worldview in music, sometimes seem to be said directly about Richter). To understand this seeming paradox means to understand something very essential in the pianist’s interpretations of the works of Bartók, Shostakovich, Hindemith, Berg.

And another distinguishing feature of Richter’s works is a clear internal organization. It was said earlier that in everything that is done by people in art – writers, artists, actors, musicians – their purely human “I” always shines through; Homo sapiens manifests itself in activities, shines through it. Richter, as others know him, is intolerant of any manifestations of negligence, sloppy attitude to business, organically does not tolerate what could be associated with “by the way” and “somehow.” An interesting touch. Behind him are thousands of public speeches, and each was taken into account by him, recorded in special notebooks: that played where and when. The same innate tendency to strict orderliness and self-discipline – in the pianist’s interpretations. Everything in them is planned in detail, weighed and distributed, everything is absolutely clear: in intentions, techniques and methods of stage embodiment. Richter’s logic of material organization is especially prominent in the works of large forms included in the artist’s repertoire. Such as Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto (famous recording with Karajan), Prokofiev’s Fifth Concerto with Maazel, Beethoven’s First Concerto with Munsch; concertos and sonata cycles by Mozart, Schumann, Liszt, Rachmaninoff, Bartok and other authors.

People who knew Richter well said that during his numerous tours, visiting different cities and countries, he did not miss the opportunity to look into the theater; Opera is especially close to him. He is a passionate fan of cinema, a good film for him is a real joy. It is known that Richter is a longtime and ardent lover of painting: he painted himself (experts assure that he was interesting and talented), spent hours in museums in front of paintings he liked; his house often served for vernissages, exhibitions of works by this or that artist. And one more thing: from a young age he was not left with a passion for literature, he was in awe of Shakespeare, Goethe, Pushkin, Blok … Direct and close contact with various arts, a huge artistic culture, an encyclopedic outlook – all this illuminates Richter’s performance with a special light, makes it phenomenon.

At the same time—another paradox in the pianist’s art!—Richter’s personified “I” never claims to be the demiurge in the creative process. In the last 10-15 years this has been especially noticeable, which, however, will be discussed later. Most likely, one sometimes thinks at the musician’s concerts, it would be to compare the individual-personal in his interpretations with the underwater, invisible part of the iceberg: it contains multi-ton power, it is the basis for what is on the surface; from prying eyes, however, it is hidden – and completely … Critics have written more than once about the artist’s ability to “dissolve” without a trace in the performed, explicit and a characteristic feature of his stage appearance. Speaking about the pianist, one of the reviewers once referred to the famous words of Schiller: the highest praise for an artist is to say that we forget about him behind his creations; they seem to be addressed to Richter – that’s who really makes you forget about himself for what he does… Apparently, some natural features of the musician’s talent make themselves felt here – typology, specificity, etc. In addition, here is the fundamental creative setting.

This is where another, perhaps the most amazing ability of Richter as a concert performer, originates – the ability to creatively reincarnate. Crystallized in him to the highest degrees of perfection and professional skill, she puts him in a special place in the circle of colleagues, even the most eminent ones; in this respect he is almost unrivaled. Neuhaus, who attributed the stylistic transformations at Richter’s performances to the category of the highest merits of an artist, wrote after one of his clavirabends: “When he played Schumann after Haydn, everything became different: the piano was different, the sound was different, the rhythm was different, the character of expression was different; and it’s so clear why – it was Haydn, and that was Schumann, and S. Richter with the utmost clarity managed to embody in his performance not only the appearance of each author, but also his era ” (Neigauz G. Svyatoslav Richter // Reflections, memories, diaries. P. 240.).

There is no need to talk about Richter’s constant successes, the successes are all the greater (the next and last paradox) because the public is usually not allowed to admire at Richter’s evenings everything that it is used to admiring at the evenings of many famous “aces” of pianism: not in instrumental virtuosity generous with effects , neither luxurious sound “decor”, nor brilliant “concert” …

This has always been characteristic of Richter’s performing style – a categorical rejection of everything outwardly catchy, pretentious (the seventies and eighties only brought this trend to the maximum possible). Everything that could distract the audience from the main and main thing in music – focus on the merits performerAnd not executable. Playing the way Richter plays is probably not enough for stage experience alone, no matter how great it may be; only one artistic culture – even unique in scale; natural talent – even a gigantic one … Here something else is required. A certain complex of purely human qualities and traits. People who know Richter closely speak with one voice about his modesty, disinterestedness, altruistic attitude towards the environment, life, and music.

For several decades, Richter has been moving forward non-stop. It would seem that he goes on easily and elatedly, but in reality he makes his way through endless, merciless, inhuman labor. Many hours of classes, which were described above, still remain the norm of his life. Little has changed here over the years. Unless more time is devoted to working with the instrument. For Richter believes that with age it is necessary not to reduce, but to increase the creative load – if you set yourself the goal of maintaining the performing “form” …

In the eighties, many interesting events and accomplishments took place in the artist’s creative life. First of all, one cannot help but recall the December Evenings – this one-of-a-kind festival of arts (music, painting, poetry), to which Richter gives a lot of energy and strength. The December Evenings, which have been held since 1981 at the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, have now become traditional; thanks to radio and television, they have found the widest audience. Their subjects are diverse: classics and modernity, Russian and foreign art. Richter, the initiator and inspirer of the “Evenings”, delves into literally everything during their preparation: from the preparation of programs and the selection of participants to the most insignificant, it would seem, details and trifles. However, there are practically no trifles for him when it comes to art. “Little things create perfection, and perfection is not a trifle” – these words of Michelangelo could become an excellent epigraph to Richter’s performance and all his activities.

At the December Evenings, another facet of Richter’s talent was revealed: together with director B. Pokrovsky, he took part in the production of B. Britten’s operas Albert Herring and The Turn of the Screw. “Svyatoslav Teofilovich worked from early morning until late at night,” recalls the director of the Museum of Fine Arts I. Antonova. “Held a huge number of rehearsals with musicians. I worked with illuminators, he checked literally every light bulb, everything to the smallest detail. He himself went with the artist to the library to select English engravings for the design of the performance. I didn’t like the costumes – I went to television and rummaged through the dressing room for several hours until I found what suited him. The whole staging part was thought out by him.

Richter still tours a lot both in the USSR and abroad. In 1986, for example, he gave about 150 concerts. The number is downright staggering. Almost twice the usual, generally accepted concert norm. Exceeding, by the way, the “norm” of Svyatoslav Teofilovich himself – previously, as a rule, he did not give more than 120 concerts a year. The routes of Richter’s tours themselves in the same 1986, which covered almost half the world, looked extremely impressive: it all started with performances in Europe, then followed by a long tour of the cities of the USSR (the European part of the country, Siberia, the Far East), then – Japan, where Svyatoslav Teofilovich had 11 solo clavirabends – and again concerts in his homeland, only now in the reverse order, from east to west. Something of this kind was repeated by Richter in 1988 – the same long series of large and not too big cities, the same chain of continuous performances, the same endless moving from place to place. “Why so many cities and these particular ones?” Svyatoslav Teofilovich was once asked. “Because I haven’t played them yet,” he replied. “I want, I really want to see the country. […] Do you know what attracts me? geographic interest. Not “wanderlust”, but that’s it. In general, I do not like to stay too long in one place, nowhere … There is nothing surprising in my trip, no feat, it’s just my desire.

Me interesting, this has motion. Geography, new harmonies, new impressions – this is also a kind of art. That’s why I’m happy when I leave some place and there will be something further new. Otherwise life is not interesting.” (Rikhter Svyatoslav: “There is nothing surprising in my trip.”: From the travel notes of V. Chemberdzhi // Sov. Music. 1987. No. 4. P. 51.).

An increasing role in Richter’s stage practice has recently been played by chamber-ensemble music-making. He has always been an excellent ensemble player, he liked to perform with singers and instrumentalists; in the seventies and eighties this became especially noticeable. Svyatoslav Teofilovich often plays with O. Kagan, N. Gutman, Yu. Bashmet; among his partners one could see G. Pisarenko, V. Tretyakov, the Borodin Quartet, youth groups under the direction of Y. Nikolaevsky and others. A kind of community of performers of various specialties was formed around him; critics began to talk, not without some pathos, about the “Richter galaxy”… Naturally, the creative evolution of musicians who are close to Richter is largely under his direct and strong influence – although he most likely does not make any decisive efforts for this. And yet… His close devotion to work, his creative maximalism, his purposefulness cannot but infect, testify the pianist’s relatives. Communicating with him, people begin to do what, it would seem, is beyond their strength and capabilities. “He has blurred the line between practice, rehearsal and concert,” says cellist N. Gutman. “Most musicians would consider at some stage that the work is ready. Richter is just starting to work on it at this very moment.”

Much is striking in the “late” Richter. But perhaps most of all – his inexhaustible passion for discovering new things in music. It would seem that with his huge repertoire accumulations – why look for something that he has not performed before? Is it necessary? … And yet in his programs of the seventies and eighties one can find a number of new works that he had not played before – for example, Shostakovich, Hindemith, Stravinsky, and some other authors. Or this fact: for over 20 years in a row, Richter participated in a music festival in the city of Tours (France). And not once during this time did he repeat himself in his programs …

Has the pianist’s style of playing changed lately? His concert-performing style? Yes and no. No, because in the main Richter remained himself. The foundations of his art are too stable and powerful for any significant modifications. At the same time, some of the tendencies characteristic of his playing in the past years have received further continuation and development today. First of all – that “implicitness” of Richter the performer, which has already been mentioned. That characteristic, unique feature of his performing manner, thanks to which the listeners get the feeling that they are directly, face to face, meeting with the authors of the performed works – without any interpreter or intermediary. And it makes an impression as strong as it is unusual. No one here can compare with Svyatoslav Teofilovich …

At the same time, it is impossible not to see that the emphasized objectivity of Richter as an interpreter – the uncomplicatedness of his performance with any subjective impurities – has a consequence and a side effect. A fact is a fact: in a number of interpretations of the pianist of the seventies and eighties, one sometimes feels a certain “distillation” of emotions, some kind of “extra-personality” (perhaps it would be more correct to say “over-personality”) of musical statements. Sometimes the internal detachment from the audience that perceives the environment makes itself felt. Sometimes, in some of his programs, Richter looked a little bit abstract as an artist, not allowing himself anything – so, at least, it seemed from the outside – that would go beyond the textbook accurate reproduction of the material. We remember that G. G. Neuhaus once lacked “humanity” in his world-famous and illustrious student – “despite all the spiritual height of performance.” Justice demands to be noted: what Genrikh Gustavovich spoke about has by no means disappeared with time. Rather the opposite…

(It is possible that everything we are talking about now is the result of Richter’s long-term, continuous and super-intensive stage activity. Even this could not but affect him.)

As a matter of fact, some of the listeners had frankly confessed before that they felt at Richter’s evenings the feeling that the pianist was somewhere at a distance from them, on some kind of high pedestal. And earlier, Richter seemed to many like the proud and majestic figure of an artist-“celestial”, an Olympian, inaccessible to mere mortals … Today, these feelings are perhaps even stronger. The pedestal looks even more impressive, grander and… more distant.

And further. On the previous pages, Richter’s tendency to creative self-deepening, introspection, “philosophicalness” was noted. (“The whole process of musical performance takes place in himself”…) In recent years, he happens to soar in such high layers of the spiritual stratosphere that it is rather difficult for the public, at least for some part of it, to catch direct contact with them. And enthusiastic applause after the performances of the artist does not change this fact.

All of the above is not criticism in the usual, commonly used sense of the word. Svyatoslav Teofilovich Richter is too significant a creative figure, and his contribution to world art is too great to be approached with standard critical standards. At the same time, there is no point in turning away from some special, only inherent features of the performing appearance. Moreover, they reveal certain patterns of his many years of evolution as an artist and a person.

At the end of the conversation about Richter of the seventies and eighties, it is impossible not to notice that the pianist’s Artistic Calculation has now become even more accurate and verified. The edges of the sound constructions constructed by him became even clearer and sharper. A clear confirmation of this is the latest concert programs of Svyatoslav Teofilovich, and his recordings, in particular pieces from Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons, Rachmaninov’s etudes-paintings, as well as Shostakovich’s Quintet with “Borodinians”.

… Richter’s relatives report that he is almost never completely satisfied with what he has done. He always feels some distance between what he really achieves on stage and what he would like to achieve. When, after some concerts, he is told – from the bottom of his heart and with full professional responsibility – that he has almost reached the limit of what is possible in musical performance, he answers – just as frankly and responsibly: no, no, I alone know how it should be …

Therefore, Richter remains Richter.

G. Tsypin, 1990