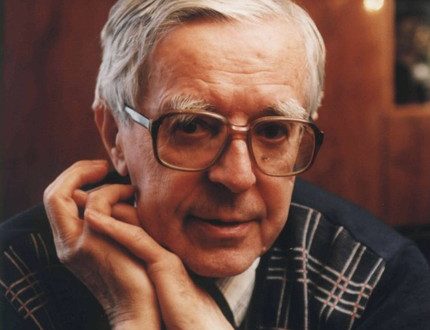

Shura Cherkassky |

Shura Cherkassky

At the concerts of this artist, listeners often have a strange feeling: it seems that it is not an experienced artist who is performing before you, but a young child prodigy. The fact that on the stage at the piano there is a small man with a childish, diminutive name, almost childish height, with short arms and tiny fingers – all this only suggests an association, but it is born by the artist’s performing style itself, marked not only by youthful spontaneity, but sometimes downright childish naivete. No, his game cannot be denied a kind of unique perfection, or attractiveness, even fascination. But even if you get carried away, it is difficult to give up the idea that the world of emotions into which the artist immerses you does not belong to a mature, respectable person.

Meanwhile, the artistic path of Cherkassky is calculated for many decades. A native of Odessa, he was inseparable from music from early childhood: at the age of five he composed a grand opera, at ten he conducted an amateur orchestra and, of course, played the piano for many hours a day. He received his first music lessons in the family, Lidia Cherkasskaya was a pianist and played in St. Petersburg, taught music, among her students is the pianist Raymond Leventhal. In 1923, the Cherkassky family, after long wanderings, settled in the United States, in the city of Baltimore. Here the young virtuoso soon made his debut before the public and had a stormy success: all tickets for subsequent concerts were sold out in a matter of hours. The boy amazed the audience not only with his technical skill, but also with the poetic feeling, and by that time his repertoire already included more than two hundred works (including concertos by Grieg, Liszt, Chopin). After his debut in New York (1925), the World newspaper observed: “With careful upbringing, preferably in one of the musical greenhouses, Shura Cherkassky can grow in a few years into the piano genius of his generation.” But neither then nor later did Cherkassky study systematically anywhere, except for a few months of studies at the Curtis Institute under the guidance of I. Hoffmann. And from 1928 he devoted himself completely to concert activity, encouraged by the favorable reviews of such luminaries of pianism as Rachmaninov, Godovsky, Paderevsky.

Since then, for more than half a century, he has been in continuous “swimming” on the concert sea, again and again striking listeners from different countries with the originality of his playing, causing heated debate among them, taking upon himself a hail of critical arrows, from which sometimes he cannot protect and armor of audience applause. It cannot be said that his playing did not change at all over time: in the fifties, gradually, he began to more and more persistently master previously inaccessible areas – sonatas and major cycles of Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms. But still, on the whole, the general contours of his interpretations remain the same, and the spirit of a kind of carefree virtuosity, even recklessness, hovers over them. And that’s all – “it turns out”: despite the short fingers, despite the seeming lack of strength …

But this inevitably entails reproaches – for superficiality, self-will and striving for external effects, neglecting all and sundry traditions. Joachim Kaiser, for example, believes: “A virtuoso like the diligent Shura Cherkassky, of course, is capable of causing surprise and applause from the ingenuous listeners – but at the same time, to the question of how we play the piano today, or how the modern culture correlates with the masterpieces of piano literature, Cherkassky’s brisk diligence is unlikely to give an answer.

Critics talk – and not without reason – about the “taste of cabaret”, about the extremes of subjectivism, about liberties in handling the author’s text, about stylistic imbalance. But Cherkassky does not care about the purity of style, the integrity of the concept – he just plays, plays the way he feels the music, simply and naturally. So what, then, is the attraction and fascination of his game? Is it only technical fluency? No, of course, no one is surprised by this now, and besides, dozens of young virtuosos play both faster and louder than Cherkassky. His strength, in short, is precisely in the spontaneity of feeling, the beauty of sound, and also in the element of surprise that his playing always carries, in the pianist’s ability to “read between the lines.” Of course, in large canvases this is often not enough – it requires scale, philosophical depth, reading and conveying the author’s thoughts in all their complexity. But even here in Cherkassky one sometimes admires moments full of originality and beauty, striking finds, especially in the sonatas of Haydn and early Mozart. Closer to his style is the music of romantics and contemporary authors. This is full of lightness and poetry “Carnival” by Schumann, sonatas and fantasies by Mendelssohn, Schubert, Schumann, “Islamei” by Balakirev, and finally, sonatas by Prokofiev and “Petrushka” by Stravinsky. As for piano miniatures, here Cherkassky is always in his element, and in this element there are few equals to him. Like no one else, he knows how to find interesting details, highlight side voices, set off charming danceability, achieve incendiary brilliance in the plays of Rachmaninoff and Rubinstein, Poulenc’s Toccata and Mann-Zucca’s “Training the Zuave”, Albéniz’s “Tango” and dozens of other spectacular “little things”.

Of course, this is not the main thing in the art of pianoforte; the reputation of a great artist is not usually built on this. But such is Cherkassky – and he, as an exception, has the “right to exist.” And once you get used to his playing, you involuntarily begin to find attractive aspects in his other interpretations, you begin to understand that the artist has his own, unique and strong personality. And then his playing no longer causes irritation, you want to listen to him again and again, even being aware of the artistic limitations of the artist. Then you understand why some very serious critics and connoisseurs of the piano put it so highly, call it, like R. Kammerer, “heir to the mantle of I. Hoffman”. For this, right, there are reasons. “Cherkassky,” wrote B. Jacobs in the late 70s is one of the original talents, he is a primordial genius and, like some others in this small number, is much closer to what we are only now re-realizing as the true spirit of the great classics and romantics than many “stylish” creations of the dried taste standard of the middle of the XNUMXth century. This spirit presupposes a high degree of creative freedom of the performer, although this freedom should not be confused with the right to arbitrariness. Many other experts agree with such a high assessment of the artist. Here are two more authoritative opinions. Musicologist K. AT. Kürten writes: “His breathtaking keyboarding is not of the kind that has more to do with sports than art. His stormy strength, impeccable technique, piano artistry are entirely at the service of flexible musicality. Cantilena blossoms under Cherkassky’s hands. He is able to color slow parts in fantastic sound colors, and, like few others, knows a lot about rhythmic subtleties. But in the most stunning moments, he retains that vital brilliance of piano acrobatics, which makes the listener wonder in surprise: where does this small, frail man get such extraordinary energy and intense elasticity that allow him to victoriously storm all the heights of virtuosity? “Paganini Piano” is rightly called Cherkassky for his magical art. The strokes of the portrait of a peculiar artist are complemented by E. Orga: “At his best, Cherkassky is a consummate piano master, and he brings to his interpretations a style and manner that is simply unmistakable. Touché, pedalization, phrasing, a sense of form, the expressiveness of secondary lines, the nobility of gestures, poetic intimacy – all this is in his power. He merges with the piano, never letting it conquer him; he speaks in a leisurely voice. Never seeking to do anything controversial, he nevertheless does not skim the surface. His calmness and poise complete this XNUMX% ability to make a big impression. Perhaps he lacks the harsh intellectualism and absolute power that we find in, say, Arrau; he does not have the incendiary charm of Horowitz. But as an artist, he finds a common language with the public in a way that even Kempf is inaccessible. And in his highest achievements he has the same success as Rubinstein. For example, in pieces like Albéniz’s Tango, he gives examples that cannot be surpassed. Не слышать, как Черкасский играет эти пьесы, значит, упустить нечто такое, что просто невозможно описать словами.

Repeatedly – both in the pre-war period and in the 70-80s, the artist came to the USSR, and Russian listeners could experience his artistic charm for themselves, objectively assess what place belongs to this unusual musician in the colorful panorama of the pianistic art of our days.

Since the 1950s Cherkassky settled in London, where he died in 1995. Buried at Highgate Cemetery in London.

Grigoriev L., Platek Ya.