The history of Gregorian chant: the recitative of the prayer will respond like a chorale

Contents

Gregorian chants, Gregorian chant… Most of us automatically associate these words with the Middle Ages (and quite rightly). But the roots of this liturgical chant go back to the times of late antiquity, when the first Christian communities appeared in the Middle East.

Gregorian chants, Gregorian chant… Most of us automatically associate these words with the Middle Ages (and quite rightly). But the roots of this liturgical chant go back to the times of late antiquity, when the first Christian communities appeared in the Middle East.

The foundations of the Gregorian chant were formed during the 2nd-6th centuries under the influence of the musical structure of antiquity (odic chants), and the music of the countries of the East (ancient Jewish psalmody, melismatic music of Armenia, Syria, Egypt).

The earliest and only documentary evidence depicting Gregorian chant presumably dates back to the 3rd century. AD It concerns the recording of a Christian hymn in Greek notation on the back of a report of grain collected on papyrus found at Oxyrhynchus, Egypt.

In fact, this sacred music received the name “Gregorian” from , who basically systematized and approved the main body of official chants of the Western Church.

Features of Gregorian chant

The foundation of Gregorian chant is the speech of prayer, the mass. Based on how words and music interact in choral chants, a division of Gregorian chants arose into:

- syllabic (this is when one syllable of the text corresponds to one musical tone of the chant, the perception of the text is clear);

- pneumatic (small chants appear in them – two or three tones per syllable of the text, the perception of the text is easy);

- melismatic (large chants – an unlimited number of tones per syllable, the text is difficult to perceive).

Gregorian chant itself is monodic (that is, fundamentally one-voice), but this does not mean that the chants could not be performed by a choir. According to the type of performance, singing is divided into:

- antiphonal, in which two groups of singers alternate (absolutely all psalms are sung this way);

- responsorwhen solo singing alternates with choral singing.

The mode-intonation basis of Gregorian chant consists of 8 modal modes, called church modes. This is explained by the fact that in the early Middle Ages exclusively diatonic sound was used (the use of sharps and flats was considered a temptation from the evil one and was even prohibited for some time).

Over time, the original rigid framework for the performance of Gregorian chants began to collapse under the influence of many factors. This includes the individual creativity of musicians, always striving to go beyond the norms, and the emergence of new versions of texts for previous melodies. This unique musical and poetic arrangement of previously created compositions was called a trope.

Gregorian chant and the development of notation

Initially, chants were written down without notes in so-called tonars – something like instructions for singers – and in graduals, singing books.

Starting from the 10th century, fully notated song books appeared, recorded using non-linear non-neutral notation. Neumas are special icons, squiggles, which were placed above the texts in order to somehow simplify the life of singers. Using these icons, the musicians were supposed to be able to guess what the next melodic move would be.

By the 12th century, widespread square-linear notation, which logically completed the non-neutral system. Its main achievement can be called the rhythmic system – now the singers could not only predict the direction of the melodic movement, but also knew exactly how long a particular note should be maintained.

The importance of Gregorian chant for European music

Gregorian chant became the foundation for the emergence of new forms of secular music in the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, going from the organum (one of the forms of medieval two-voices) to the melodically rich mass of the High Renaissance.

Gregorian chant largely determined the thematic (melodic) and constructive (the form of the text is projected onto the form of the musical work) basis of Baroque music. This is truly a fertile field on which the shoots of all subsequent forms of European – in the broad sense of the word – musical culture have sprouted.

The relationship between words and music

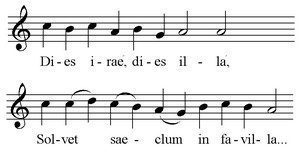

Dies Irae (Day of Wrath) – the most famous chorale of the Middle Ages

The history of Gregorian chant is inextricably linked with the history of the Christian church. Liturgical performance based on psalmody, melismatic chant, hymns and masses was already internally distinguished by genre diversity, which allowed Gregorian chants to survive to this day.

The chorales also reflected early Christian asceticism (simple psalmodic singing in early church communities) with the emphasis on words over melody.

Time has given rise to hymn performance, when the poetic text of a prayer is harmoniously combined with a musical melody (a kind of compromise between words and music). The appearance of melismatic chants – in particular the jubilees at the end of hallelujah – marked the final supremacy of musical harmony over the word and at the same time reflected the establishment of the final dominance of Christianity in Europe.

Gregorian chant and liturgical drama

Gregorian music played an important role in the development of the theater. Songs on biblical and gospel themes gave rise to dramatization of performances. These musical mysteries gradually, on church holidays, left the walls of cathedrals and entered the squares of medieval cities and settlements.

Having united with traditional forms of folk culture (costume performances of traveling acrobats, troubadours, singers, storytellers, jugglers, tightrope walkers, fire swallowers, etc.), liturgical drama laid the foundation for all subsequent forms of theatrical performance.

The most popular stories of liturgical drama are the gospel stories about the worship of the shepherds and the arrival of the wise men with gifts to the infant Christ, about the atrocities of King Herod, who ordered the extermination of all the babies of Bethlehem, and the story of the resurrection of Christ.

With its release to the “people,” liturgical drama moved from obligatory Latin to national languages, which made it even more popular. Church hierarchs already then well understood that art is the most effective means of marketing, expressed in modern terms, capable of attracting the widest segments of the population to the temple.

Gregorian chant, having given a lot to modern theatrical and musical culture, nevertheless, has lost nothing, forever remaining an undivided phenomenon, a unique synthesis of religion, faith, music and other forms of art. And to this day he fascinates us with the frozen harmony of the universe and worldview, cast in the chorale.