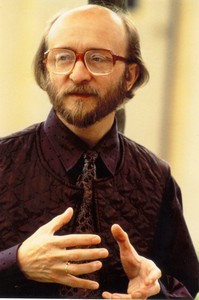

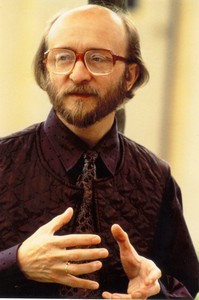

Alexey Borisovich Lyubimov (Alexei Lubimov) |

Alexei Lubimov

Aleksey Lyubimov is not an ordinary figure in the Moscow musical and performing environment. He started his career as a pianist, but today there are no less reasons to call him a harpsichordist (or even an organist). Gained fame as a soloist; now he is almost a professional ensemble player. As a rule, he does not play what others play – for example, until the mid-eighties he practically never performed the works of Liszt, he played Chopin only two or three times – but he puts into his programs that no one except him performs.

Alexei Borisovich Lyubimov was born in Moscow. It so happened that among the neighbors of the Lyubimov family at home was a well-known teacher – pianist Anna Danilovna Artobolevskaya. She drew attention to the boy, ascertained his abilities. And then he ended up at the Central Music School, among the students of A.D. Artobolevskaya, under whose supervision he studied for over ten years – from the first grade to the eleventh.

“I still remember the lessons with Alyosha Lyubimov with a joyful feeling,” said A.D. Artobolevskaya. – I remember when he first came to my class, he was touchingly naive, ingenuous, direct. Like most gifted children, he was distinguished by a lively and quick reaction to musical impressions. With pleasure, he learned various pieces that were asked to him, tried to compose something himself.

About 13-14 years old, an internal fracture began to be noticed in Alyosha. A heightened craving for the new woke up in him, which never left him later. He passionately fell in love with Prokofiev, began to peer more closely into musical modernity. I am convinced that Maria Veniaminovna Yudina had a huge influence on him in this.

M. V. Yudina Lyubimov is something like a pedagogical “grandson”: his teacher, A. D. Artobolevskaya, took lessons from an outstanding Soviet pianist in her youth. But most likely Yudina noticed Alyosha Lyubimov and singled him out among others not only for this reason. He impressed her with the very warehouse of his creative nature; in turn, he saw in her, in her activities, something close and akin to himself. “The concert performances of Maria Veniaminovna, as well as personal communication with her, served as a huge musical impulse for me in my youth,” says Lyubimov. On the example of Yudina, he learned high artistic integrity, uncompromising in creative matters. Probably, partly from her and his taste for musical innovations, fearlessness in addressing the most daring creations of modern composer thought (we will talk about this later). Finally, from Yudina and something in the manner of playing Lyubimov. He not only saw the artist on the stage, but also met with her in the house of A. D. Artobolevskaya; he knew Maria Veniaminovna’s pianism very well.

At the Moscow Conservatory, Lyubimov studied for some time with G. G. Neuhaus, and after his death with L. N. Naumov. To tell the truth, he, as an artistic individuality – and Lyubimov came to the university as an already established individuality – did not have much in common with the romantic school of Neuhaus. Nevertheless, he believes that he learned a lot from his conservative teachers. This happens in art, and often: enrichment through contacts with the creatively opposite…

In 1961, Lyubimov participated in the All-Russian competition of performing musicians and won first place. His next victory – in Rio de Janeiro at the international competition of instrumentalists (1965), – the first prize. Then – Montreal, piano competition (1968), fourth prize. Interestingly, both in Rio de Janeiro and Montreal, he receives special awards for the best performance of contemporary music; his artistic profile by this time emerges in all its specificity.

After graduating from the conservatory (1968), Lyubimov lingered for some time within its walls, accepting the position of teacher of the chamber ensemble. But in 1975 he leaves this work. “I realized that I need to focus on one thing…”

However, it is now that his life is developing in such a way that he is “dispersed”, and quite intentionally. His regular creative contacts are established with a large group of artists – O. Kagan, N. Gutman, T. Grindenko, P. Davydova, V. Ivanova, L. Mikhailov, M. Tolpygo, M. Pechersky … Joint concert performances are organized in the halls of Moscow and other cities of the country, a series of interesting, always in some way original themed evenings are announced. Ensembles of various composition are created; Lyubimov often acts as their leader or, as the posters sometimes say, “Music coordinator”. His repertory conquests are being carried out more and more intensively: on the one hand, he is constantly delving into the bowels of early music, mastering the artistic values created long before J. S. Bach; on the other hand, he asserts his authority as a connoisseur and specialist in the field of musical modernity, versed in its most diverse aspects – up to rock music and electronic experiments, inclusive. It should also be said about Lyubimov’s passion for ancient instruments, which has been growing over the years. Does all this apparent diversity of types and forms of labor have its own internal logic? Undoubtedly. There is both wholeness and organicity. In order to understand this, one must, at least in general terms, become familiar with Lyubimov’s views on the art of interpretation. At some points they diverge from the generally accepted ones.

He is not too fascinated (he does not hide it) performing as a self-contained sphere of creative activity. Here he holds, no doubt, in a special position among his colleagues. It looks almost original today, when, in the words of G. N. Rozhdestvensky, “the audience comes to a symphony concert to listen to the conductor, and to the theater – to listen to the singer or look at the ballerina” (Rozhdestvensky G. N. Thoughts on music. – M., 1975. P. 34.). Lyubimov emphasizes that he is interested in music itself – as an artistic entity, phenomenon, phenomenon – and not in a specific range of issues related to the possibility of its various stage interpretations. It is not important for him whether he should enter the stage as a soloist or not. It is important to be “inside the music”, as he once put it in a conversation. Hence his attraction to joint music-making, to the chamber-ensemble genre.

But that’s not all. There is another. There are too many stencils on today’s concert stage, Lyubimov notes. “For me, there is nothing worse than a stamp…” This is especially noticeable when applied to authors representing the most popular trends in the art of music, who wrote, say, in the XNUMXth century or at the turn of the XNUMXth. What is attractive for Lyubimov’s contemporaries – Shostakovich or Boulez, Cage or Stockhausen, Schnittke or Denisov? The fact that in relation to their work there are no interpretative stereotypes yet. “The musical performance situation develops here unexpectedly for the listener, unfolds according to laws that are unpredictable in advance …” says Lyubimov. The same, in general, in the music of the pre-Bach era. Why do you often find artistic examples of the XNUMXth-XNUMXth centuries in his programs? Because their performing traditions have long been lost. Because they require some new interpretive approaches. New – For Lyubimov, this is fundamentally important.

Finally, there is another factor that determines the direction of its activity. He is convinced that music should be performed on the instruments for which it was created. Some works are on the piano, others on the harpsichord or virginal. Today it is taken for granted to play the pieces of the old masters on a piano of modern design. Lyubimov is against this; this distorts the artistic appearance of both the music itself and those who wrote it, he argues. They remain unrevealed, many subtleties — stylistic, timbre-coloristic — which are inherent in the poetic relics of the past, are reduced to nothing. Playing, in his opinion, should be on genuine old instruments or skillfully made copies of them. He performs Rameau and Couperin on the harpsichord, Bull, Byrd, Gibbons, Farneby on the virginal, Haydn and Mozart on the hammer piano (hammerklavier), organ music by Bach, Kunau, Frescobaldi and their contemporaries on the organ. If necessary, he can resort to many other tools, as it happened in his practice, and more than once. It is clear that in the long run this distances him from pianism as a local performing profession.

From what has been said, it is not difficult to conclude that Lyubimov is an artist with his own ideas, views, and principles. Somewhat peculiar, sometimes paradoxical, taking him away from the usual, well-trodden paths in the performing arts. (It is no coincidence, we repeat once again, that in his youth he was close to Maria Veniaminovna Yudina, it is no coincidence that she marked him with her attention.) All this in itself commands respect.

Although he does not show a particular inclination to the role of a soloist, he still has to perform solo numbers. No matter how eager he is to completely immerse himself “inside the music”, to hide himself, his artistic appearance, when he is on stage, shines through the performance with all clarity.

He is restrained behind the instrument, internally collected, disciplined in feelings. Maybe a little closed. (Sometimes one has to hear about him – “closed nature”.) Alien to any impulsiveness in stage statements; the sphere of his emotions is organized as strictly as it is reasonable. Behind everything he does, there is a well-thought-out musical concept. Apparently, much in this artistic complex comes from the natural, personal qualities of Lyubimov. But not only from them. In his game – clear, carefully calibrated, rational in the highest sense of the word – one can also see a very definite aesthetic principle.

Music, as you know, is sometimes compared with architecture, musicians with architects. Lyubimov in his creative method is really akin to the latter. While playing, he seems to build musical compositions. As if erecting sound structures in space and time. Criticism noted at the time that the “constructive element” dominates in his interpretations; so it was and remains. In everything the pianist has proportionality, architectonic calculation, strict proportionality. If we agree with B. Walter that “the basis of all art is order”, one cannot but admit that the foundations of Lyubimov’s art are hopeful and strong …

Usually the artists of his warehouse emphasized objective in his approach to interpreted music. Lyubimov has long and fundamentally denied performing individualism and anarchy. (In general, he believes that the stage method, based on a purely individual interpretation of the performed masterpieces by a concert performer, will become a thing of the past, and the debatability of this judgment does not bother him in the least.) The author for him is the beginning and end of the entire interpretative process, of all the problems that arise in this connection. . An interesting touch. A. Schnittke, having once written a review of a pianist’s performance (Mozart’s compositions were in the program), “was surprised to find that she (review.— Mr. C.) not so much about Lyubimov’s concerto as about Mozart’s music” (Schnittke A. Subjective notes on objective performance // Sov. Music. 1974. No. 2. P. 65.). A. Schnittke came to a reasonable conclusion that “do not be

such a performance, the listeners would not have so many thoughts about this music. Perhaps the highest virtue of a performer is to affirm the music he plays, and not himself. (Ibid.). All of the above clearly outline the role and significance intellectual factor in the activities of Lyubimov. He belongs to the category of musicians who are remarkable primarily for their artistic thought – accurate, capacious, unconventional. Such is his individuality (even if he himself is against its overly categorical manifestations); moreover, perhaps its strongest side. E. Ansermet, a prominent Swiss composer and conductor, was perhaps not far from the truth when he stated that “there is an unconditional parallelism between music and mathematics” (Anserme E. Conversations about music. – L., 1976. S. 21.). In the creative practice of some artists, whether they write music or perform it, this is quite obvious. In particular, Lyubimov.

Of course, not everywhere his manner is equally convincing. Not all critics are satisfied, for example, by his performance of Schubert – impromptu, waltzes, German dances. We have to hear that this composer in Lyubimov is sometimes somewhat emotional, that he lacks simple-heartedness, sincere affection, warmth here … Perhaps this is so. But, generally speaking, Lyubimov is usually precise in his repertory aspirations, in the selection and compilation of programs. He knows well where his repertory possessions, and where the possibility of failure cannot be ruled out. Those authors to whom he refers, whether they are our contemporaries or old masters, usually do not conflict with his performing style.

And a few more touches to the portrait of the pianist – for a better drawing of its individual contours and features. Lyubimov is dynamic; as a rule, it is convenient for him to conduct musical speech at moving, energetic tempos. He has a strong, definite finger strike—excellent “articulation,” to use an expression usually used to denote such important qualities for performers as clear diction and intelligible stage pronunciation. He is strongest of all, perhaps, in the musical schedule. Somewhat less – in watercolor sound recording. “The most impressive thing about his playing is the electrified toccato” (Ordzhonikidze G. Spring Meetings with Music//Sov. Music. 1966. No. 9. P. 109.), one of the music critics wrote in the mid-sixties. To a large extent, this is true today.

In the second half of the XNUMXs, Lyubimov gave another surprise to listeners who seemed to be accustomed to all sorts of surprises in his programs.

Earlier it was said that he usually does not accept what most concert musicians gravitate towards, preferring little-studied, if not completely unexplored repertoire areas. It was said that for a long time he practically did not touch the works of Chopin and Liszt. So, all of a sudden, everything changed. Lyubimov began to devote almost entire clavirabends to the music of these composers. In 1987, for example, he played in Moscow and some other cities of the country three Sonnets of Petrarch, the Forgotten Waltz No. 1 and Liszt’s F-minor (concert) etude, as well as Barcarolle, ballads, nocturnes and mazurkas by Chopin; the same course was continued in the following season. Some people took this as yet another eccentricity on the part of the pianist – you never know how many of them, they say, are on his account … However, for Lyubimov in this case (as, indeed, always) there was an internal justification in what he did: “I I have been aloof from this music for a long time, that I see absolutely nothing surprising in my suddenly awakened attraction to it. I want to say with all certainty: turning to Chopin and Liszt was not some kind of speculative, “head” decision on my part – for a long time, they say, I haven’t played these authors, I should have played … No, no, I was just drawn to them. Everything came from somewhere inside, in terms of purely emotional.

Chopin, for example, has become almost a half-forgotten composer for me. I can say that I discovered it for myself – as sometimes undeservedly forgotten masterpieces of the past are discovered. Perhaps that is why I woke up such a lively, strong feeling for him. And most importantly, I felt that I did not have any hardened interpretive cliches in relation to Chopin’s music – therefore, I can play it.

The same thing happened with Liszt. Especially close to me today is the late Liszt, with its philosophical nature, its complex and sublime spiritual world, mysticism. And, of course, with its original and refined sound-coloring. It is with great pleasure that I now play Gray Clouds, Bagatelles without Key, and other works by Liszt of the last period of his work.

Perhaps my appeal to Chopin and Liszt had such a background. I have long noticed, performing the works of the authors of the XNUMXth century, that many of them bear a clearly distinguishable reflection of romanticism. In any case, I clearly see this reflection – no matter how paradoxical at first glance – in the music of Silvestrov, Schnittke, Ligeti, Berio … In the end, I came to the conclusion that modern art owes much more to romanticism than was previously believed. When I was imbued with this thought, I was drawn, so to speak, to the primary sources – to the era from which so much went, received its subsequent development.

By the way, I am attracted today not only by the luminaries of romanticism – Chopin, Liszt, Brahms … I am also of great interest to their younger contemporaries, composers of the first third of the XNUMXth century, who worked at the turn of two eras – classicism and romanticism, connecting them with each other. I have in mind now such authors as Muzio Clementi, Johann Hummel, Jan Dussek. There is also a lot in their compositions that helps to understand the further ways of development of world musical culture. Most importantly, there is a lot of bright, talented people who have not lost their artistic value even today.”

In 1987, Lyubimov played the Symphony Concerto for two pianos with Dussek’s orchestra (the part of the second piano was performed by V. Sakharov, accompanied by the orchestra conducted by G. Rozhdestvensky) – and this work, as he expected, aroused great interest among the audience.

And one more hobby of Lyubimov should be noted and explained. No less, if not more unexpected, than his fascination with Western European romanticism. This is an old romance, which the singer Viktoria Ivanovna “discovered” for him recently. “Actually, the essence is not in the romance as such. I am generally attracted by the music that sounded in the aristocratic salons of the middle of the last century. After all, it served as an excellent means of spiritual communication between people, made it possible to convey the deepest and most intimate experiences. In many ways, it is the opposite of the music that was performed on a large concert stage – pompous, loud, sparkling with dazzlingly bright, luxurious sound outfits. But in salon art – if it is really real, high art – you can feel very subtle emotional nuances that are characteristic of it. That’s why it’s precious to me.”

At the same time, Lyubimov does not stop playing music that was close to him in previous years. Attachment to distant antiquity, he does not change and is not going to change. In 1986, for example, he launched the Golden Age of the Harpsichord series of concerts, planned for several years ahead. As part of this cycle, he performed the Suite in D minor by L. Marchand, the suite “Celebrations of the great and ancient Menestrand” by F. Couperin, as well as a number of other plays by this author. Of undoubted interest to the public was the program “Gallant festivities at Versailles”, where Lyubimov included instrumental miniatures by F. Dandrieu, L. K. Daken, J. B. de Boismortier, J. Dufly and other French composers. We should also mention Lyubimov’s ongoing joint performances with T. Grindenko (violin compositions by A. Corelli, F. M. Veracini, J. J. Mondonville), O. Khudyakov (suites for flute and digital bass by A. Dornell and M. de la Barra ); one cannot but recall, finally, the musical evenings dedicated to F. E. Bach …

However, the essence of the matter is not in the amount found in the archives and played in public. The main thing is that Lyubimov today shows himself, as before, as a skillful and knowledgeable “restorer” of musical antiquity, skillfully returning it to its original form – the graceful beauty of its forms, the gallantry of sound decoration, the special subtlety and delicacy of musical statements.

… In recent years, Lyubimov has had several interesting trips abroad. I must say that earlier, before them, for quite a long time (about 6 years) he did not travel outside the country at all. And only because, from the point of view of some officials who led the musical culture in the late seventies and early eighties, he performed “not those” works that should have been performed. His predilection for contemporary composers, for the so-called “avant-garde” – Schnittke, Gubaidulina, Sylvestrov, Cage, and others – did not, to put it mildly, sympathize “at the top”. Forced domesticity at first upset Lyubimov. And who of the concert artists would not be upset in his place? However, the feelings subsided later. “I realized that there are some positive aspects in this situation. It was possible to concentrate entirely on work, on learning new things, because no distant and long-term absences from home distracted me. And indeed, during the years that I was a “travel restricted” artist, I managed to learn many new programs. So there is no evil without good.

Now, as they said, Lyubimov has resumed his normal touring life. Recently, together with the orchestra conducted by L. Isakadze, he played the Mozart Concerto in Finland, gave several solo clavirabends in the GDR, Holland, Belgium, Austria, etc.

Like every real, great master, Lyubimov has own public. To a large extent, these are young people – the audience is restless, greedy for a change of impressions and various artistic innovations. Earn sympathy such public, enjoying its steady attention for a number of years is not an easy task. Lyubimov was able to do it. Is there still a need for confirmation that his art really carries something important and necessary for people?

G. Tsypin, 1990