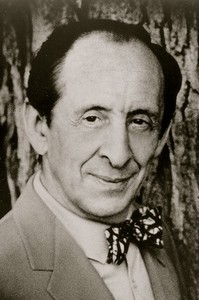

Vladimir Horowitz (Vladimir Horowitz) |

Vladimir Horowitz

A concert by Vladimir Horowitz is always an event, always a sensation. And not only now, when his concerts are so rare that anyone can be the last, but also at the time of the beginning. It’s always been that way. Since that early spring of 1922, when a very young pianist first appeared on the stages of Petrograd and Moscow. True, his very first concerts in both capitals were held at half-empty halls – the name of the debutant said little to the public. Only a few connoisseurs and specialists have heard about this amazingly talented young man who graduated from the Kyiv Conservatory in 1921, where his teachers were V. Pukhalsky, S. Tarnovsky and F. Blumenfeld. And the next day after his performances, the newspapers unanimously announced Vladimir Horowitz as a rising star on the pianistic horizon.

Having made several concert tours around the country, Horowitz set off in 1925 to “conquer” Europe. Here history repeated itself: at his first performances in most cities – Berlin, Paris, Hamburg – there were few listeners, for the next – tickets were taken from the fight. True, this had little effect on the fees: they were scanty. The beginning of the noisy glory was laid – as often happens – by a happy accident. In the same Hamburg, a breathless entrepreneur ran to his hotel room and offered to replace the ill soloist in Tchaikovsky’s First Concerto. I had to speak in half an hour. Hastily drinking a glass of milk, Horowitz rushed into the hall, where the aged conductor E. Pabst only had time to tell him: “Watch my stick, and God willing, nothing terrible will happen.” After a few bars, the stunned conductor himself watched the soloist play, and when the concert was over, the audience sold out tickets for his solo performance in an hour and a half. This is how Vladimir Horowitz triumphantly entered the musical life of Europe. In Paris, after his debut, the magazine Revue Musical wrote: “Sometimes, nevertheless, there is an artist who has a genius for interpretation – Liszt, Rubinstein, Paderevsky, Kreisler, Casals, Cortot … Vladimir Horowitz belongs to this category of artist-kings.”

New applause brought Horowitz debut on the American continent, which took place in early 1928. After performing first the Tchaikovsky Concerto and then the solo program, he was given, according to The Times newspaper, “the most stormy meeting that a pianist can count on.” In the following years, while living in the US, Paris and Switzerland, Horowitz toured and recorded extremely intensively. The number of his concerts per year reaches a hundred, and in terms of the number of released records, he soon surpasses most modern pianists. His repertoire is wide and varied; the basis is the music of the romantics, especially Liszt and Russian composers – Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov, Scriabin. The best features of Horowitz’s performing image of that pre-war period are reflected in his recording of Liszt’s Sonata in B minor, made in 1932. It impresses not only with its technical whirlwind, the intensity of the game, but also with the depth of feeling, truly Liszt scale, and the relief of details. Liszt’s rhapsody, Schubert’s impromptu, Tchaikovsky’s concertos (No. 1), Brahms (No. 2), Rachmaninov (No. 3) and much more are marked by the same features. But along with the merits, critics rightly find in Horowitz’s acting superficiality, a desire for external effects, for frapping listeners with technical escapades. Here is the opinion of the prominent American composer W. Thomson: “I do not claim that Horowitz’s interpretations are basically false and unjustified: sometimes they are, sometimes they are not. But someone who has never listened to the works he performed could easily conclude that Bach was a musician like L. Stokowski, Brahms was a kind of frivolous, nightclub-working Gershwin, and Chopin was a gypsy violinist. These words, of course, are too harsh, but such an opinion was not isolated. Horowitz sometimes made excuses, defended himself. He said: “Piano playing consists of common sense, heart and technical means. Everything must be developed equally: without common sense you will fail, without technology you are an amateur, without a heart you are a machine. So the profession is fraught with dangers. But when, in 1936, due to an appendicitis operation and subsequent complications, he was forced to interrupt his concert activity, he suddenly felt that many of the reproaches were not groundless.

The pause forced him to take a fresh look at himself, as if from the outside, to reconsider his relationship with music. “I think that as an artist I have grown during these forced holidays. In any case, I discovered a lot of new things in my music,” the pianist emphasized. The validity of these words is easily confirmed by comparing records recorded before 1936 and after 1939, when Horowitz, at the insistence of his friend Rachmaninov and Toscanini (whose daughter he is married to), returned to the instrument.

In this second, more mature period of 14 years, Horowitz expands his range considerably. On the one hand, he is from the late 40s; constantly and more often plays Beethoven’s sonatas and Schumann’s cycles, miniatures and major works by Chopin, trying to find a different interpretation of the music of great composers; on the other hand, it enriches new programs with modern music. In particular, after the war, he was the first to play Prokofiev’s 6th, 7th and 8th sonatas, Kabalevsky’s 2nd and 3rd sonatas in America, moreover, he played with amazing brilliance. Horowitz gives life to some of the works of American authors, including the Barber Sonata, and at the same time includes in concert use the works of Clementi and Czerny, which were then considered only part of the pedagogical repertoire. The activity of the artist at that time becomes very intense. It seemed to many that he was at the zenith of his creative potential. But as the “concert machine” of America again subjugated him, voices of skepticism, and often irony, began to be heard. Some call the pianist a “magician”, a “rat-catcher”; again they talk about his creative impasse, about indifference to music. The first imitators appear on the stage, or rather even Horowitz’s imitators – superbly equipped technically, but internally empty, young “technicians”. Horowitz had no students, with a few exceptions: Graffman, Jainis. And, giving lessons, he constantly urged “it is better to make your own mistakes than to copy the mistakes of others.” But those who copied Horowitz did not want to follow this principle: they were betting on the right card.

The artist was painfully aware of the signs of the crisis. And now, having played in February 1953 a gala concert on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of his debut at Carnegie Hall, he again leaves the stage. This time for a long time, for 12 years.

True, the complete silence of the musician lasted less than a year. Then, little by little, he again begins to record mainly at home, where RCA has equipped an entire studio. The records come out again one after another – sonatas by Beethoven, Scriabin, Scarlatti, Clementi, Liszt’s rhapsodies, works by Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Rachmaninoff, Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, own transcriptions of F. Sousa’s march “Stars and Stripes”, “Wedding March “Mendelssohn-Liszt, a fantasy from” Carmen “… In 1962, the artist breaks with the company RCA, dissatisfied with the fact that he provides little food for advertising, and begins to cooperate with the Columbia company. Each new record of his convinces that the pianist does not lose his phenomenal virtuosity, but becomes an even more subtle and profound interpreter.

“The artist, who is forced to constantly stand face to face with the public, becomes devastated without even realizing it. He constantly gives without receiving in return. Years of avoiding public speaking helped me finally find myself and my own true ideals. During the crazy years of concerts – there, here and everywhere – I felt myself becoming numb – spiritually and artistically, ”he will say later.

Admirers of the artist believed that they would meet with him “face to face”. Indeed, on May 9, 1965, Horowitz resumed his concert activity with a performance at Carnegie Hall. Interest in his concert was unprecedented, tickets sold out in a matter of hours. A significant part of the audience were young people who had never seen him before, people for whom he was a legend. “He looked exactly the same as when he last appeared here 12 years ago,” G. Schonberg commented. – High shoulders, the body is almost motionless, slightly inclined to the keys; only hands and fingers worked. For many young people in the audience, it was almost as if they were playing Liszt or Rachmaninov, the legendary pianist everyone talks about but nobody has heard of.” But even more important than Horowitz’s outward immutability was the deep inner transformation of his game. “Time has not stopped for Horowitz in the twelve years since his last public appearance,” wrote New York Herald Tribune reviewer Alan Rich. – The dazzling brilliance of his technique, the incredible power and intensity of performance, fantasy and colorful palette – all this has been preserved intact. But at the same time, a new dimension appeared in his game, so to speak. Of course, when he left the concert stage at the age of 48, he was a fully formed artist. But now a deeper interpreter has come to Carnegie Hall, and a new “dimension” in his playing can be called musical maturity. Over the past few years, we have seen a whole galaxy of young pianists convincing us that they can play quickly and technically confidently. And it is quite possible that Horowitz’s decision to return to the concert stage just now was due to the realization that there is something that even the most brilliant of these young people need to be reminded of. During the concert, he taught a whole series of valuable lessons. It was a lesson in extracting quivering, sparkling colors; it was a lesson in the use of rubato with impeccable taste, especially vividly demonstrated in the works of Chopin, it was a brilliant lesson in combining the details and the whole in each piece and reaching the highest climaxes (especially with Schumann). Horowitz let “we feel the doubts that plagued him all these years as he contemplated his return to the concert hall. He demonstrated what a precious gift he now possessed.

That memorable concert, which heralded the revival and even the new birth of Horowitz, was followed by four years of frequent solo performances (Horowitz has not played with the orchestra since 1953). “I’m tired of playing in front of a microphone. I wanted to play for people. The perfection of technology is also tiring, ”the artist admitted. In 1968, he also made his first television appearance in a special film for young people, where he performed many gems of his repertoire. Then – a new 5-year pause, and instead of concerts – new magnificent recordings: Rachmaninoff, Scriabin, Chopin. And on the eve of his 70th birthday, the remarkable master returned to the public for the third time. Since then, he has not performed too often, and only during the daytime, but his concerts are still a sensation. All these concerts are recorded, and the records released after that make it possible to imagine what an amazing pianistic form the artist has retained by the age of 75, what artistic depth and wisdom he has acquired; allow at least partly to understand what the style of the “late Horowitz” is. Partly “because, as American critics emphasize, this artist never has two identical interpretations. Of course, Horowitz’s style is so peculiar and definite that any more or less sophisticated listener is able to recognize him at once. A single measure of any of his interpretations on the piano can define this style better than any words. But it is impossible, however, not to single out the most outstanding qualities – a striking coloristic variety, lapidary balance of his fine technique, a huge sound potential, as well as overly developed rubato and contrasts, spectacular dynamic oppositions in the left hand.

Such is Horowitz today, Horowitz, familiar to millions of people from records and thousands from concerts. It is impossible to predict what other surprises he is preparing for the listeners. Each meeting with him is still an event, still a holiday. Concerts in big cities of the USA, with which the artist celebrated the 50th anniversary of his American debut, became such holidays for his admirers. One of them, on January 8, 1978, was especially significant as the artist’s first performance with an orchestra in a quarter of a century: Rachmaninov’s Third Concerto was performed, Y. Ormandy conducted. A few months later, Horowitz’s first Chopin evening took place at Carnegie Hall, which later turned into an album of four records. And then – evenings dedicated to his 75th birthday … And every time, going out on the stage, Horowitz proves that for a true creator, age does not matter. “I am convinced that I am still developing as a pianist,” he says. “I become calmer and more mature as the years go by. If I felt that I was unable to play, I would not dare to appear on the stage “…