Martti Talvela (Martti Talvela) |

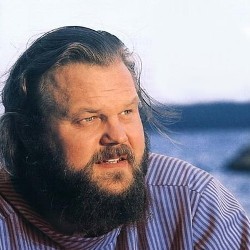

Martti Talvela

Finland has given the world a lot of singers and singers, from the legendary Aino Akte to the star Karita Mattila. But the Finnish singer is first and foremost a bass, the Finnish singing tradition from Kim Borg is passed down from generation to generation with basses. Against the Mediterranean “three tenors”, Holland put up three countertenors, Finland – three basses: Matti Salminen, Jaakko Ryuhanen and Johan Tilly recorded a similar disc together. In this chain of tradition, Martti Talvela is the golden link.

Classical Finnish bass in appearance, voice type, repertoire, today, twelve years after his death, he is already a legend of the Finnish opera.

Martti Olavi Talvela was born on February 4, 1935 in Karelia, in Hiitol. But his family did not live there for long, because as a result of the “winter war” of 1939-1940, this part of Karelia turned into a closed border zone on the territory of the Soviet Union. The singer never managed to visit his native places again, although he visited Russia more than once. In Moscow, he was heard in 1976, when he performed in a concert at the celebration of the 200th anniversary of the Bolshoi Theater. Then, a year later, he came again, sang in the performances of the theater of two monarchs – Boris and Philip.

Talvela’s first profession is a teacher. By the will of fate, he received a teacher’s diploma in the city of Savonlinna, where in the future he had to sing a lot and for a long time lead the largest opera festival in Scandinavia. His singing career began in 1960 with a victory at a competition in the city of Vasa. Having made his debut in the same year in Stockholm as Sparafucile, Talvela sang there for two years at the Royal Opera, while continuing his studies.

Martti Talvela’s international career began rapidly – the Finnish giant immediately became an international sensation. In 1962, he performed in Bayreuth as Titurel – and Bayreuth became one of his main summer residences. In 1963 he was Grand Inquisitor at La Scala, in 1965 he was King Heinrich at the Vienna Staatsoper, in 19 he was Hunding in Salzburg, in 7 he was Grand Inquisitor at the Met. From now on, for more than two decades, his main theaters are the Deutsche Oper and the Metropolitan Opera, and the main parts are the Wagnerian kings Mark and Daland, Verdi’s Philip and Fiesco, Mozart’s Sarastro.

Talvela sang with all the major conductors of his time – with Karajan, Solti, Knappertsbusch, Levine, Abbado. Karl Böhm should be especially singled out – Talvela can rightfully be called a Böhm singer. Not only because the Finnish bass often performed with Böhm and made many of his best opera and oratorio recordings with him: Fidelio with Gwyneth Jones, The Four Seasons with Gundula Janowitz, Don Giovanni with Fischer-Dieskau, Birgit Nilsson and Martina Arroyo, Rhine Gold, Tristan und Isolde with Birgit Nilsson, Wolfgang Windgassen and Christa Ludwig. The two musicians are very close to each other in their performing style, the type of expression, precisely found a combination of energy and restraint, some kind of innate craving for classicism, for an impeccably harmonious performance dramaturgy, which each one built on his own territory.

Foreign triumphs of Talvela responded at home with something more than blind reverence for the illustrious compatriot. For Finland, the years of Talvela’s activity are the years of the “opera boom”. This is not only the growth of the listening and watching public, the birth of small semi-private semi-state companies in many cities and towns, the flourishing of a vocal school, the debut of a whole generation of opera conductors. This is also the productivity of composers, which has already become familiar, self-evident. In 2000, in a country of 5 million people, 16 premieres of new operas took place – a miracle that arouses envy. In the fact that it happened, Martti Talvela played a significant role – by his example, his popularity, his wise policy in Savonlinna.

The summer opera festival in the 500-year-old Olavinlinna fortress, which is surrounded by the town of Savonlinna, was started back in 1907 by Aino Akte. Since then, it has been interrupted, then resumed, struggling with rain, wind (there was no reliable roof over the fortress courtyard where performances are held until last summer) and endless financial problems – it is not so easy to gather a large opera audience among forests and lakes. Talvela took over the festival in 1972 and directed it for eight years. This was a decisive period; Savonlinna has been the opera mecca of Scandinavia ever since. Talvela acted here as a playwright, gave the festival an international dimension, included it in the world opera context. The consequences of this policy are the popularity of performances in the fortress far beyond the borders of Finland, the influx of tourists, which today ensures the festival’s stable existence.

In Savonlinna, Talvela sang many of his best roles: Boris Godunov, the prophet Paavo in Jonas Kokkonen’s The Last Temptation. And another iconic role: Sarastro. The production of The Magic Flute, staged in Savonlinna in 1973 by director August Everding and conductor Ulf Söderblom, has since become one of the symbols of the festival. In today’s repertoire, The Flute is the most venerable performance that is still being revived (despite the fact that a rare production lives here for more than two or three years). The imposing Talvela-Sarastro in an orange robe, with a sun on his chest, is now seen as the legendary patriarch of Savonlinna, and he was then 38 years old (he first sang Titurel at 27)! Over the years, the idea of Talvel has been formed as a monumental, immovable block, as if related to the walls and towers of Olavinlinna. The notion is false. Fortunately, there are videos of a nimble and agile artist with great, instant reactions. And there are audio recordings that give the true image of the singer, especially in the chamber repertoire – Martti Talvela sang chamber music not from time to time, between theatrical engagements, but constantly, continuously giving concerts all over the world. His repertoire included songs by Sibelius, Brahms, Wolf, Mussorgsky, Rachmaninoff. And how did you have to sing in order to conquer Vienna with the songs of Schubert in the mid-1960s? Probably the way he later recorded The Winter Journey with pianist Ralph Gotoni (1983). Talvela demonstrates here the cat’s flexibility of intonation, incredible sensitivity and amazing speed of reaction to the smallest details of the musical text. And enormous energy. Listening to this recording, you physically feel how he leads the pianist. The initiative behind him, reading, subtext, form and dramaturgy are from him, and in every note of this exciting lyrical interpretation one can feel the wise intellectualism that has always distinguished Talvela.

One of the best portraits of the singer belongs to his friend and colleague Yevgeny Nesterenko. Once Nesterenko was visiting a Finnish bass in his house in Inkilyanhovi. There, on the shore of the lake, there was a “black bathhouse”, built about 150 years ago: “We took a steam bath, then somehow naturally got into a conversation. We sit on the rocks, two naked men. And we are talking. About what? That’s the main thing! Martti asks, for example, how I interpret Shostakovich’s Fourteenth Symphony. And here is Mussorgsky’s Songs and Dances of Death: you have two recordings – the first you did in this way, and the second in another way. Why, what explains it. And so on. I confess that in my life I have not had occasion to talk about art with singers. We talk about anything, but not about the problems of art. But with Martti we talked a lot about art! Moreover, we were not talking about how to perform something technologically, better or worse, but about the content. This is how we spent time after the bath.”

Perhaps this is the most correctly captured image – a conversation about a Shostakovich symphony in a Finnish bath. Because Martti Talvela, with his broadest horizons and great culture, in his singing combined the German meticulousness of the presentation of the text with the Italian cantilena, remained a somewhat exotic figure in the opera world. This image of him is brilliantly used in “Abduction from the Seraglio” directed by August Everding, where Talvela sings Osmina. What do Turkey and Karelia have in common? Exotic. There is something primal, powerful, raw and awkward about Osmin Talvely, his scene with Blondchen is a masterpiece.

This exotic for the West, barbaric image, latently accompanying the singer, did not disappear over the years. On the contrary, it stood out more and more clearly, and next to the Wagnerian, Mozartian, Verdiian roles, the role of the “Russian bass” was strengthened. In the 1960s or 1970s, Talvela could be heard at the Metropolitan Opera in almost any repertoire: sometimes he was the Grand Inquisitor in Don Carlos under the baton of Abbado (Philippa was sung by Nikolai Gyaurov, and their bass duet was unanimously recognized as a classic) , then he, along with Teresa Stratas and Nikolai Gedda, appears in The Bartered Bride directed by Levine. But in his last four seasons, Talvela came to New York only for three titles: Khovanshchina (with Neeme Jarvi), Parsifal (with Levine), Khovanshchina again and Boris Godunov (with Conlon). Dositheus, Titurel and Boris. More than twenty years of cooperation with the “Met” ends with two Russian parties.

On December 16, 1974, Talvela triumphantly sang Boris Godunov at the Metropolitan Opera. The theater then turned to Mussorgsky’s original orchestration for the first time (Thomas Schippers conducted). Two years later, this edition was first recorded in Katowice, conducted by Jerzy Semkow. Surrounded by the Polish troupe, Martti Talvela sang Boris, Nikolai Gedda sang the Pretender.

This entry is extremely interesting. They have already resolutely and irrevocably returned to the author’s version, but they still sing and play as if the score was written by Rimsky-Korsakov’s hand. The choir and orchestra sound so beautifully combed, so filled, so roundly perfect, the cantilena is so sung, and Semkov often, especially in Polish scenes, drags everything out and drags out the tempo. Academic “Central European” well-being blows up none other than Martti Talvela. He is building his part again, like a playwright. In the coronation scene, a regal bass sounds – deep, dark, voluminous. And a bit of “national color”: a little bit of dashing intonations, in the phrase “And there to call the people to a feast” – valiant prowess. But then Talvela parted with both royalty and boldness easily and without regret. As soon as Boris is face to face with Shuisky, the manner changes dramatically. This is not even Chaliapin’s “talk”, Talvela’s dramatic singing – rather Sprechgesang. Talvela immediately begins the scene with Shuisky with the highest exertion of forces, not for a second weakening the heat. What will happen next? Further, when the chimes start to play, a perfect phantasmagoria in the spirit of expressionism will begin, and Jerzy Semkov, who changes unrecognizably in the scenes with Talvela-Boris, will give us such Mussorgsky as we know today – without the slightest touch of academic averageness.

Around this scene is a scene in a chamber with Xenia and Theodore, and a scene of death (again with Theodore), which Talvela unusually brings together with each other with the timbre of his voice, that special warmth of sound, the secret of which he owned. By singling out and connecting with each other both scenes of Boris with children, he seems to endow the tsar with traits of his own personality. And in conclusion, he sacrifices the beauty and fullness of the upper “E” (which he had was magnificent, at the same time light and full) for the sake of the truth of the image … And through Boris’s speech, no, no, yes, Wagner’s “stories” peep through – one inadvertently recalls that Mussorgsky played by heart the scene of Wotan’s farewell to Brunnhilde.

Of today’s Western bassists who sing a lot of Mussorgsky, Robert Hall is perhaps closest to Talvela: the same curiosity, the same intent, intense peering into every word, the same intensity with which both singers search for meaning and adjust rhetorical accents. Talvela’s intellectualism forced him to check every detail of the role analytically.

When Russian basses still rarely performed in the West, Martti Talvela seemed to replace them in his signature Russian parts. He had unique data for this – a gigantic growth, a powerful build, a huge, dark voice. His interpretations testify to what extent he penetrated the secrets of Chaliapin – Yevgeny Nesterenko has already told us how Martti Talvela was able to listen to the recordings of his colleagues. A man of European culture and a singer who brilliantly mastered the universal European technique, Talvela may have embodied our dream of an ideal Russian bass in something better, more perfect than our compatriots can do. And after all, he was born in Karelia, on the territory of the former Russian Empire and the current Russian Federation, in that short historical period when this land was Finnish.

Anna Bulycheva, Big Magazine of the Bolshoi Theatre, No. 2, 2001