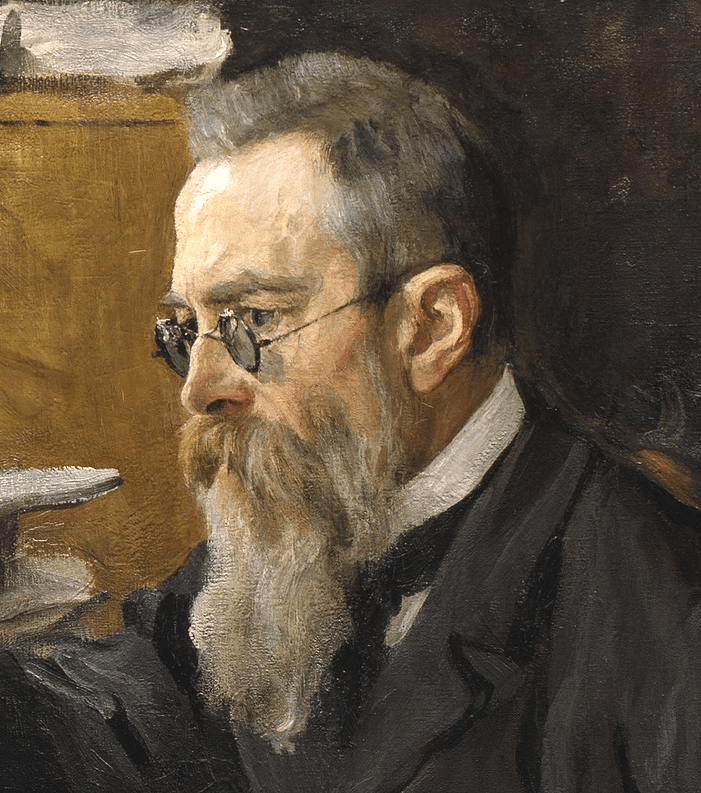

Nikolai Andreevich Rimsky-Korsakov |

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Neither his talent, nor his energy, nor his boundless benevolence towards his students and comrades, ever weakened. The glorious life and deeply national activity of such a person should be our pride and joy. … how much can be pointed out in the entire history of music of such high natures, such great artists and such extraordinary people as Rimsky-Korsakov? V. Stasov

Almost 10 years after the opening of the first Russian conservatory in St. Petersburg, in the fall of 1871, a new professor of composition and orchestration appeared within its walls. Despite his youth – he was in his twenty-eighth year – he had already gained fame as the author of original compositions for orchestra: Overtures on Russian themes, Fantasies on the themes of Serbian folk songs, a symphonic picture based on the Russian epic “Sadko” and a suite on the plot of an oriental fairy tale “Antar” . In addition, many romances were written, and work on the historical opera The Maid of Pskov was in full swing. No one could have imagined (least of all the director of the conservatory, who invited N. Rimsky-Korsakov) that he became a composer with almost no musical training.

Rimsky-Korsakov was born into a family far from artistic interests. Parents, according to family tradition, prepared the boy for service in the Navy (the uncle and older brother were sailors). Although musical abilities were revealed very early, there was no one to seriously study in a small provincial town. Piano lessons were given by a neighbor, then a familiar governess and a student of this governess. Musical impressions were supplemented by folk songs performed by an amateur mother and uncle and cult singing in the Tikhvin Monastery.

In St. Petersburg, where Rimsky-Korsakov came to enroll in the Naval Corps, he visits the opera house and at concerts, recognizes Ivan Susanin and Glinka’s Ruslan and Lyudmila, Beethoven’s symphonies. In St. Petersburg, he finally has a real teacher – an excellent pianist and educated musician F. Canille. He advised the gifted student to compose music himself, introduced him to M. Balakirev, around whom young composers grouped – M. Mussorgsky, C. Cui, later A. Borodin joined them (Balakirev’s circle went down in history under the name “Mighty Handful”).

None of the “Kuchkists” did not take a course of special musical training. The system by which Balakirev prepared them for independent creative activity was as follows: he immediately proposed a responsible topic, and then, under his leadership, in joint discussions, in parallel with the study of the works of major composers, all the difficulties that arose in the process of composing were solved.

Seventeen-year-old Rimsky-Korsakov was advised by Balakirev to start with a symphony. Meanwhile, the young composer, who graduated from the Naval Corps, was supposed to set off on a round-the-world voyage. He returned to music and art friends only after 3 years. Genius talent helped Rimsky-Korsakov quickly master the musical form, and bright colorful orchestration, and composing techniques, bypassing the school foundations. Having created complex symphonic scores and working on an opera, the composer did not know the very basics of musical science and was not familiar with the necessary terminology. And suddenly an offer to teach at the conservatory! .. “If I learned even a little bit, if I knew even a little bit more than I really knew, then it would be clear to me that I cannot and have no right to take up the proposed the point is that becoming a professor would be both stupid and unscrupulous on my part, ”recalled Rimsky-Korsakov. But not dishonesty, but the highest responsibility, he showed, starting to learn the very foundations that he was supposed to teach.

The aesthetic views and worldview of Rimsky-Korsakov were formed in the 1860s. under the influence of the “Mighty Handful” and its ideologist V. Stasov. At the same time, the national basis, the democratic orientation, the main themes and images of his work were determined. In the next decade, Rimsky-Korsakov’s activities are multifaceted: he teaches at the conservatory, improves his own composing technique (writes canons, fugues), holds the position of inspector of brass bands of the Naval Department (1873-84) and conducts symphony concerts, replaces the director of the Free Music School Balakirev and prepares for publication (together with Balakirev and Lyadov) the scores of both Glinka’s operas, records and harmonizes folk songs (the first collection was published in 1876, the second – in 1882).

An appeal to Russian musical folklore, as well as a detailed study of Glinka’s opera scores in the process of preparing them for publication, helped the composer overcome the speculativeness of some of his compositions, which arose as a result of intensive studies in composition technique. Two operas written after The Maid of Pskov (1872) — May Night (1879) and The Snow Maiden (1881) — embodied Rimsky-Korsakov’s love for folk rituals and folk song and his pantheistic worldview.

Creativity of the composer of the 80s. mainly represented by symphonic works: “The Tale” (1880), Sinfonietta (1885) and Piano Concerto (1883), as well as the famous “Spanish Capriccio” (1887) and “Scheherazade” (1888). At the same time, Rimsky-Korsakov worked in the Court Choir. But he devotes most of his time and energy to preparing for the performance and publication of the operas of his late friends – Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina and Borodin’s Prince Igor. It is likely that this intense work on opera scores led to the fact that Rimsky-Korsakov’s own work developed during these years in the symphonic sphere.

The composer returned to the opera only in 1889, having created the enchanting Mlada (1889-90). Since the mid 90s. one after another is followed by The Night Before Christmas (1895), Sadko (1896), the prologue to The Maid of Pskov — the one-act Boyar Vera Sheloga and The Tsar’s Bride (both 1898). In the 1900s The Tale of Tsar Saltan (1900), Servilia (1901), Pan Governor (1903), The Tale of the Invisible City of Kitezh (1904) and The Golden Cockerel (1907) are created.

Throughout his creative life, the composer also turned to vocal lyrics. In 79 of his romances, the poetry of A. Pushkin, M. Lermontov, A. K. Tolstoy, L. May, A. Fet, and from foreign authors J. Byron and G. Heine are presented.

The content of Rimsky-Korsakov’s work is diverse: it also revealed the folk-historical theme (“The Woman of Pskov”, “The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh”), the sphere of lyrics (“The Tsar’s Bride”, “Servilia”) and everyday drama (“Pan Voyevoda”), reflected the images of the East (“Antar”, “Scheherazade”), embodied the features of other musical cultures (“Serbian Fantasy”, “Spanish Capriccio”, etc.). But more characteristic of Rimsky-Korsakov are fantasy, fabulousness, diverse connections with folk art.

The composer created a whole gallery of unique in its charm, pure, gently lyrical female images – both real and fantastic (Pannochka in “May Night”, Snegurochka, Martha in “The Tsar’s Bride”, Fevronia in “The Tale of the Invisible City of Kitezh”) , images of folk singers (Lel in “The Snow Maiden”, Nezhata in “Sadko”).

Formed in the 1860s. the composer remained faithful to progressive social ideals all his life. On the eve of the first Russian revolution of 1905 and in the period of reaction that followed it, Rimsky-Korsakov wrote the operas Kashchei the Immortal (1902) and The Golden Cockerel, which were perceived as a denunciation of the political stagnation that reigned in Russia.

The creative path of the composer lasted more than 40 years. Entering it as a successor to the traditions of Glinka, he and in the XX century. adequately represents Russian art in world musical culture. Rimsky-Korsakov’s creative and musical-public activities are multifaceted: composer and conductor, author of theoretical works and reviews, editor of works by Dargomyzhsky, Mussorgsky and Borodin, he had a strong influence on the development of Russian music.

Over 37 years of teaching at the conservatory, he taught more than 200 composers: A. Glazunov, A. Lyadov, A. Arensky, M. Ippolitov-Ivanov, I. Stravinsky, N. Cherepnin, A. Grechaninov, N. Myaskovsky, S. Prokofiev and others. The development of oriental themes by Rimsky-Korsakov (“Antar”, “Scheherazade”, “Golden Cockerel”) was of inestimable importance for the development of national musical cultures of Transcaucasia and Central Asia, and diverse seascapes (“Sadko”, “Sheherazade”, “The Tale of Tsar Saltan”, the cycle of romances “By the Sea”, etc.) determined a lot in the plein-air sound painting of the Frenchman C. Debussy and the Italian O. Respighi.

E. Gordeeva

The work of Nikolai Andreevich Rimsky-Korsakov is a unique phenomenon in the history of Russian musical culture. The point is not only in the enormous artistic significance, colossal volume, rare versatility of his work, but also in the fact that the composer’s work almost entirely covers a very dynamic era in Russian history – from the peasant reform to the period between revolutions. One of the first works of the young musician was the instrumentation of Dargomyzhsky’s just completed The Stone Guest, the last major work of the master, The Golden Cockerel, dates back to 1906-1907: the opera was composed simultaneously with Scriabin’s Poem of Ecstasy, Rachmaninov’s Second Symphony; only four years separate the premiere of The Golden Cockerel (1909) from the premiere of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, two from Prokofiev’s debut as a composer.

Thus, the work of Rimsky-Korsakov, purely in chronological terms, constitutes, as it were, the core of Russian classical music, connecting the link between the era of Glinka-Dargomyzhsky and the XNUMXth century. Synthesizing the achievements of the St. Petersburg school from Glinka to Lyadov and Glazunov, absorbing much from the experience of Muscovites – Tchaikovsky, Taneyev, composers who performed at the turn of the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries, it was always open to new artistic trends, domestic and foreign.

A comprehensive, systematizing character is inherent in any direction of Rimsky-Korsakov’s work – composer, teacher, theorist, conductor, editor. His life activity as a whole is a complex world, which I would like to call the “Rimsky-Korsakov cosmos”. The purpose of this activity is to collect, focus the main features of the national musical and, more broadly, artistic consciousness, and ultimately to recreate an integral image of the Russian worldview (of course, in its personal, “Korsakovian” refraction). This gathering is inextricably linked with the personal, author’s evolution, just as the process of teaching, educating – not only direct students, but the entire musical environment – with self-education, self-education.

A. N. Rimsky-Korsakov, the composer’s son, speaking of the constantly renewing variety of tasks solved by Rimsky-Korsakov, successfully described the artist’s life as a “puffer-like interweaving of threads.” He, reflecting on what made the brilliant musician devote an unreasonably large part of his time and energy to “side” types of educational work, pointed to “a clear consciousness of his duty to Russian music and musicians.” “Service“- the key word in the life of Rimsky-Korsakov, just as “confession” – in the life of Mussorgsky.

It is believed that Russian music of the second half of the 1860th century clearly tends to assimilate the achievements of other arts contemporary to it, especially literature: hence the preference for “verbal” genres (from romance, song to opera, the crown of the creative aspirations of all composers of the XNUMXs generation), and in instrumental – a broad development of the principle of programming. However, it is now becoming more and more obvious that the picture of the world created by Russian classical music is not at all identical to those in literature, painting or architecture. The features of the growth of the Russian composer school are connected both with the specifics of music as an art form and with the special position of music in the national culture of the XNUMXth century, with its special tasks in understanding life.

The historical and cultural situation in Russia predetermined a colossal gap between the people who, according to Glinka, “create music” and those who wanted to “arrange” it. The rupture was profound, tragically irreversible, and its consequences are felt to this day. But, on the other hand, the multi-layered cumulative auditory experience of Russian people contained inexhaustible possibilities for the movement and growth of art. Perhaps, in music, the “discovery of Russia” was expressed with the greatest force, since the basis of its language – intonation – is the most organic manifestation of the individual human and ethnic, a concentrated expression of the spiritual experience of the people. The “multiple structure” of the national intonation environment in Russia in the middle of the century before last is one of the prerequisites for the innovation of the Russian professional music school. Gathering in a single focus of multidirectional trends – relatively speaking, from pagan, Proto-Slavic roots to the latest ideas of Western European musical romanticism, the most advanced techniques of musical technology – is a characteristic feature of Russian music of the second half of the XNUMXth century. During this period, it finally leaves the power of applied functions and becomes a worldview in sounds.

Often talking about the sixties of Mussorgsky, Balakirev, Borodin, we seem to forget that Rimsky-Korsakov belongs to the same era. Meanwhile, it is difficult to find an artist more faithful to the highest and purest ideals of his time.

Those who knew Rimsky-Korsakov later – in the 80s, 90s, 1900s – never tired of being surprised at how harshly he prosaiced himself and his work. Hence the frequent judgments about the “dryness” of his nature, his “academicism”, “rationalism”, etc. In fact, this is typical of the sixties, combined with the avoidance of excessive pathos in relation to one’s own personality, characteristic of a Russian artist. One of Rimsky-Korsakov’s students, M. F. Gnesin, expressed the idea that the artist, in a constant struggle with himself and with those around him, with the tastes of his era, at times seemed to harden, becoming in some of his statements even lower than himself. This must be kept in mind when interpreting the composer’s statements. Apparently, the remark of another student of Rimsky-Korsakov, A.V. Ossovsky, deserves even more attention: the severity, captiousness of introspection, self-control, which invariably accompanied the path of the artist, were such that a person of lesser talent simply could not stand those “breaks”, those experiments that he constantly set on himself: the author of The Maid of Pskov, like a schoolboy, sits down to problems in harmony, the author of The Snow Maiden does not miss a single performance of Wagner operas, the author of Sadko writes Mozart and Salieri, professor the academician creates Kashchei, etc. And this, too, came from Rimsky-Korsakov not only from nature, but also from the era.

His social activity was always very high, and his activity was distinguished by complete disinterestedness and undivided devotion to the idea of public duty. But, unlike Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov is not a “populist” in the specific, historical sense of the term. In the problem of the people, he always, starting with The Maid of Pskov and the poem Sadko, saw not so much the historical and social as the indivisible and eternal. Compared to the documents of Tchaikovsky or Mussorgsky in the letters of Rimsky-Korsakov, in his Chronicle there are few declarations of love for the people and for Russia, but as an artist he had a colossal sense of national dignity, and in the messianism of Russian art, in particular music, he was no less confident than Mussorgsky.

All Kuchkists were characterized by such a feature of the sixties as an endless inquisitiveness to the phenomena of life, an eternal anxiety of thought. In Rimsky-Korsakov, it focused to the greatest extent on nature, understood as the unity of the elements and man, and on art as the highest embodiment of such unity. Like Mussorgsky and Borodin, he steadily strove for “positive”, “positive” knowledge about the world. In his desire to thoroughly study all areas of musical science, he proceeded from the position – in which (like Mussorgsky) he believed very firmly, sometimes to the point of naivety – that in art there are laws (norms) that are just as objective, universal as in science. not just taste preferences.

As a result, the aesthetic and theoretical activity of Rimsky-Korsakov embraced almost all areas of knowledge about music and developed into a complete system. Its components are: the doctrine of harmony, the doctrine of instrumentation (both in the form of large theoretical works), aesthetics and form (notes of the 1890s, critical articles), folklore (collections of arrangements of folk songs and examples of creative comprehension of folk motives in compositions), teaching about mode (a large theoretical work on ancient modes was destroyed by the author, but a brief version of it has survived, as well as examples of the interpretation of ancient modes in arrangements of church chants), polyphony (considerations expressed in letters, in conversations with Yastrebtsev, etc., and also creative examples), musical education and organization of musical life (articles, but mainly educational and pedagogical activities). In all these areas, Rimsky-Korsakov expressed bold ideas, the novelty of which is often obscured by a strict, concise form of presentation.

“The creator of the Pskovityanka and the Golden Cockerel was not a retrograde. He was an innovator, but one who strove for classical completeness and proportionality of musical elements ”(Zuckerman V.A.). According to Rimsky-Korsakov, anything new is possible in any field under the conditions of a genetic connection with the past, logic, semantic conditionality, and architectonic organization. Such is his doctrine of the functionality of harmony, in which logical functions can be represented by consonances of various structures; such is his doctrine of instrumentation, which opens with the phrase: “There are no bad sonorities in the orchestra.” The system of musical education proposed by him is unusually progressive, in which the mode of learning is associated primarily with the nature of the student’s giftedness and the availability of certain methods of live music-making.

The epigraph to his book about the teacher M. F. Gnesin put the phrase from Rimsky-Korsakov’s letter to his mother: “Look at the stars, but do not look and do not fall.” This seemingly random phrase of a young cadet of the Naval Corps remarkably characterizes the position of Rimsky-Korsakov as an artist in the future. Perhaps the gospel parable of two messengers fits his personality, one of whom immediately said “I will go” – and did not go, and the other at first said “I will not go” – and went (Matt., XXI, 28-31).

In fact, during the course of Rimsky-Korsakov’s career, there are many contradictions between “words” and “deeds”. For example, no one so fiercely scolded Kuchkism and its shortcomings (suffice it to recall the exclamation from a letter to Krutikov: “Oh, Russian compositeоry – Stasov’s emphasis – they owe their lack of education to themselves! ”, A whole series of offensive statements in the Chronicle about Mussorgsky, about Balakirev, etc.) – and no one was so consistent in upholding, defending the basic aesthetic principles of Kuchkism and all his creative achievements: in 1907, a few months before his death, Rimsky-Korsakov called himself “the most convinced Kuchkist.” Few people were so critical of the “new times” in general and fundamentally new phenomena of musical culture at the turn of the century and at the beginning of the 80th century – and at the same time so deeply and fully answered the spiritual demands of the new era (“Kashchey”, “Kitezh”, ” The Golden Cockerel” and others in the later works of the composer). Rimsky-Korsakov in the 90s – early XNUMXs sometimes spoke very harshly about Tchaikovsky and his direction – and he constantly learned from his antipode: the work of Rimsky-Korsakov, his pedagogical activity, undoubtedly, was the main link between St. Petersburg and Moscow schools. Korsakov’s criticism of Wagner and his operatic reforms is even more devastating, and meanwhile, among Russian musicians, he most profoundly accepted Wagner’s ideas and creatively responded to them. Finally, none of the Russian musicians so consistently emphasized their religious agnosticism in words, and few managed to create such deep images of folk faith in their work.

The dominants of Rimsky-Korsakov’s artistic worldview were the “universal feeling” (his own expression) and the broadly understood mythologism of thinking. In the chapter from the Chronicle dedicated to The Snow Maiden, he formulated his creative process as follows: “I listened to the voices of nature and folk art and nature and took what they sang and suggested as the basis of my work.” The artist’s attention was most focused on the great phenomena of the cosmos – the sky, the sea, the sun, the stars, and on the great phenomena in people’s lives – birth, love, death. This corresponds to all the aesthetic terminology of Rimsky-Korsakov, in particular his favorite word – “contemplation“. His notes on aesthetics open with the assertion of art as a “sphere of contemplative activity”, where the object of contemplation is “the life of the human spirit and nature, expressed in their mutual relations“. Together with the unity of the human spirit and nature, the artist affirms the unity of the content of all types of art (in this sense, his own work is certainly syncretic, although on different grounds than, for example, the work of Mussorgsky, who also argued that the arts differ only in material, but not in tasks and purposes). Rimsky-Korsakov’s own words could be put as a motto for all the work of Rimsky-Korsakov: “The representation of the beautiful is the representation of infinite complexity.” At the same time, he was not alien to the favorite term of early Kuchkism – “artistic truth”, he protested only against the narrowed, dogmatic understanding of it.

Features of the aesthetics of Rimsky-Korsakov led to the discrepancy between his work and public tastes. In relation to him, it is just as legitimate to speak of incomprehensibility, as in relation to Mussorgsky. Mussorgsky, more than Rimsky-Korsakov, corresponded to his era in terms of the type of talent, in the direction of interests (generally speaking, the history of the people and the psychology of the individual), but the radicalism of his decisions turned out to be beyond the capacity of his contemporaries. In Rimsky-Korsakov’s misunderstanding was not so acute, but no less profound.

His life seemed to be very happy: a wonderful family, excellent education, an exciting trip around the world, the brilliant success of his first compositions, an unusually successful personal life, the opportunity to devote himself entirely to music, subsequently universal respect and joy to see the growth of talented students around him. Nevertheless, starting from the second opera and up to the end of the 90s, Rimsky-Korsakov was constantly faced with a misunderstanding of both “his” and “them”. The Kuchkists considered him a non-opera composer, not proficient in dramaturgy and vocal writing. For a long time there was an opinion about the lack of original melody in him. Rimsky-Korsakov was recognized for his skill, especially in the field of the orchestra, but nothing more. This protracted misunderstanding was, in fact, the main reason for the severe crisis experienced by the composer in the period after the death of Borodin and the final collapse of the Mighty Handful as a creative direction. And only from the end of the 90s, the art of Rimsky-Korsakov became more and more in tune with the era and met with recognition and understanding among the new Russian intelligentsia.

This process of mastering the ideas of the artist by the public consciousness was interrupted by subsequent events in the history of Russia. For decades, the art of Rimsky-Korsakov was interpreted (and embodied, if we are talking about the stage realizations of his operas) in a very simplistic way. The most valuable thing in it – the philosophy of the unity of man and the cosmos, the idea of worshiping the beauty and mystery of the world remained buried under the falsely interpreted categories of “nationality” and “realism”. The fate of Rimsky-Korsakov’s heritage in this sense is, of course, not unique: for example, Mussorgsky’s operas were subjected to even greater distortions. However, if in recent times there have been disputes around the figure and work of Mussorgsky, the legacy of Rimsky-Korsakov has been in honorable oblivion in recent decades. It was recognized for all the merits of an academic order, but it seemed to fall out of the public consciousness. Rimsky-Korsakov’s music is played infrequently; in those cases when his operas hit the stage, most of the dramatizations – purely decorative, leafy or popular-fabulous – testify to a decisive misunderstanding of the composer’s ideas.

It is significant that if there is a huge modern literature on Mussorgsky in all major European languages, then serious works on Rimsky-Korsakov are very few. In addition to the old books by I. Markevich, R. Hoffmann, N. Giles van der Pals, popular biographies, as well as several interesting articles by American and English musicologists on particular issues of the composer’s work, one can name only a number of works by the main Western specialist on Rimsky-Korsakov, Gerald Abraham . The result of his many years of study was, apparently, an article about the composer for the new edition of Grove’s Encyclopedic Dictionary (1980). Its main provisions are as follows: as an opera composer, Rimsky-Korsakov suffered from a complete lack of dramatic flair, an inability to create characters; instead of musical dramas, he wrote delightful musical and stage fairy tales; instead of characters, charming fantastic dolls act in them; his symphonic works are nothing more than “very brightly colored mosaics”, while he did not master vocal writing at all.

In her monograph on Glinka, O. E. Levasheva notes the same phenomenon of incomprehension in relation to Glinka’s music, classically harmonious, collected and full of noble restraint, very far from primitive ideas about “Russian exoticism” and seeming “not enough national” to foreign critics. Domestic thought about music, with a few exceptions, not only does not fight against such a point of view regarding Rimsky-Korsakov – quite common in Russia as well – but often aggravates it, emphasizing the imaginary academicism of Rimsky-Korsakov and cultivating a false opposition to Mussorgsky’s innovation.

Perhaps the time of world recognition for the art of Rimsky-Korsakov is still ahead, and the era will come when the works of the artist, who created an integral, comprehensive image of the world arranged according to the laws of rationality, harmony and beauty, will find their own, Russian Bayreuth, which Rimsky-Korsakov’s contemporaries dreamed of on the eve of 1917.

M. Rakhmanova

- Symphonic creativity →

- Instrumental creativity →

- Choral art →

- Romances →