Solmization |

Solmization (from the name of musical sounds salt и E), solfeggio, solfegging

ital. solmisazione, solfeggio, solfeggiare, French. solmisation, solfege, solfier, нем. Solmisation, solfeggioren, solmisieren, English. solmization, sol-fa

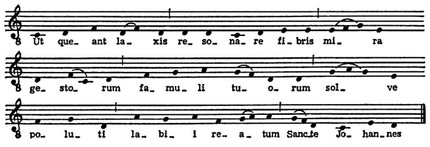

1) In the narrow sense – Middle Ages. Western European the practice of singing melodies with the syllables ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la, introduced by Guido d’Arezzo to indicate the steps of the hexachord; in a broad sense – any method of singing melodies with syllabic names. steps k.-l. scale (relative S.) or with the name. sounds corresponding to their absolute pitch (absolute pitch); learning to sing from music. The most ancient systems of syllables—Chinese (pentatonic), Indian (seven-step), Greek (tetrachordic), and Guidonian (hexachordic)—were relative. Guido used the hymn of St. John:

He used the initial syllables of each of the “lines” of the text as a name. steps of the hexachord. The essence of this method was to develop strong associations between the names and auditory representations of the steps of the hexachord. Subsequently, Guido’s syllables in a number of countries, including the USSR, began to be used to denote the absolute height of sounds; in the system of Guido himself, the syllabic name. not associated with one definition. height; for example, the syllable ut served as a name. I steps several. hexachords: natural (c), soft (f), hard (g). In view of the fact that melodies rarely fit within the limits of one hexachord, with S. it was often necessary to switch to another hexachord (mutation). This was due to the change in syllabic names. sounds (for example, the sound a had the name la in the natural hexachord, and mi in the soft hexachord). Initially, mutations were not considered an inconvenience, since the syllables mi and fa always indicated the place of the semitone and ensured the correct intonation (hence the winged definition of the Middle Ages of music theory: “Mi et fa sunt tota musica” – “Mi and fa are all music”) . The introduction of the syllable si to designate the seventh degree of the scale (X. Valrant, Antwerp, circa 1574) made mutations within one key superfluous. The seven-step “gamma through si” was used “starting from the sound of any letter designation” (E. Lullier, Paris, 1696), that is, in a relative sense. Such solmization became called. “transposing”, in contrast to the former “mutating”.

Increasing role of instr. music led in France to the use of the syllables ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la, si to denote the sounds c, d, e, f, g, a, h, and thus to the emergence of a new, absolute way of C., to- ry received the name. natural solfegging (“solfier au naturel”), since accidentals were not taken into account in it (Monteclair, Paris, 1709). In natural S., the combination of the syllables mi – fa could mean not only a small second, but also a large or increased one (ef, e-fis, es-f, es-fis), therefore the Monteclair method required the study of the tone value of the intervals, not excluding, in In case of difficulties, the use of “transposing” S. Natural S. became widespread after the appearance of the capital work “Solfeggia for teaching at the Conservatory of Music in Paris”, compiled by L. Cherubini, F. J. Gossec, E. N. Megul and others ( 1802). Here, only absolute S. was used with obligatory. instr. accompaniment, iotated in the form of a digital bass. The mastering of the skills of singing from notes was served by numerous. training exercises of two types: rhythmic. variants of scales and sequences from intervals, first in C-dur, then in other keys. Correct intonation was achieved through singing with accompaniment.

“Solfeggia” helped to navigate the system of keys; they corresponded to the major-minor, functional warehouse of modal thinking that had taken shape by that time. Already J. J. Rousseau criticized the system of natural rhythm because it neglected the names of the modal steps, did not contribute to the awareness of the tone value of the intervals, and the development of hearing. “Solfeggia” did not eliminate these shortcomings. In addition, they were intended for future professionals and provided for very time-consuming training sessions. For school singing lessons and training of amateur singers who participated in the choir. mugs, a simple method was needed. These requirements were met by the Galen-Paris-Cheve method, created on the basis of Rousseau’s ideas. The school teacher of mathematics and singing P. Galen at the initial stage of education used the improved Rousseau digital notation, in which the major scales were designated by the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, the minor scales by the numbers 6, 7, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, increased and reduced steps – with crossed out numbers (e.g. respectively  и

и  ), tonality – with a corresponding mark at the beginning of the recording (for example, “Ton Fa” meant the tonality of F-dur). Notes indicated by numbers had to be sung with the syllables ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la, si. Galen introduced modified syllables to denote alteriers. steps (ending in a vowel and in the case of an increase and in the vowel eu in the case of a decrease). However, he used digital notation only as a preparation for the study of the generally accepted five-linear notation. His student E. Pari enriched the rhythmic system. syllables (“la langue des durées” – “the language of durations”). E. Sheve, author of a number of methodical. manuals and textbooks, for 20 years the choir led circles. singing, improved the system and achieved its recognition. In 1883, the Galen-Paris-Cheve system was officially recommended for the beginning. schools, in 1905 and for cf. schools in France. In the 20th century in the conservatories of France, natural S. is used; in general education. Schools use ordinary notes, but most often they are taught to sing by ear. Around 1540, the Italian theorist G. Doni replaced the syllable ut with the syllable do for the first time for the convenience of singing. In England in the 1st half. 19th century S. Glover and J. Curwen created the so-called. “Tonic Sol-fa method” of teaching music. Supporters of this method use relative S. with syllables do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti (doh, ray, me, fah, sol, lah, te) and alphabetic notation with the initial letters of these syllables: d, r, m, f, s, 1, t. An increase in steps is expressed with the vowel i; a decrease with the help of the vowel o at the end of syllables; altered names in notation. written out in full. To determine the tonality, traditions are preserved. letter designations (for example, the mark “Key G” prescribes performance in G-dur or e-moll). First of all, characteristic intonations are mastered in the order corresponding to the modal functions of the steps: 1st stage – steps I, V, III; 2nd — steps II and VII; 3rd – steps IV and VI major; after that, the major scale as a whole, intervals, simple modulations, types of minor, alteration are given. Ch. Curwen’s work “The standard course of lessons and exercises in the Tonic Sol-fa method of teaching music” (1858) is a systematic. choir school. singing. In Germany, A. Hundegger adapted the Tonic Sol-fa method to the features of it. language, giving it a name. “Tonic Do” (1897; natural steps: do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, raised – ending in i, lowered – in and). The method became widespread after World War I (1–1914) (F. Jode in Germany and others). Further development after World War II (18–2) was carried out in the GDR by A. Stir and in Switzerland by R. Schoch. In Germany, the “Union of Tonic Do” works.

), tonality – with a corresponding mark at the beginning of the recording (for example, “Ton Fa” meant the tonality of F-dur). Notes indicated by numbers had to be sung with the syllables ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la, si. Galen introduced modified syllables to denote alteriers. steps (ending in a vowel and in the case of an increase and in the vowel eu in the case of a decrease). However, he used digital notation only as a preparation for the study of the generally accepted five-linear notation. His student E. Pari enriched the rhythmic system. syllables (“la langue des durées” – “the language of durations”). E. Sheve, author of a number of methodical. manuals and textbooks, for 20 years the choir led circles. singing, improved the system and achieved its recognition. In 1883, the Galen-Paris-Cheve system was officially recommended for the beginning. schools, in 1905 and for cf. schools in France. In the 20th century in the conservatories of France, natural S. is used; in general education. Schools use ordinary notes, but most often they are taught to sing by ear. Around 1540, the Italian theorist G. Doni replaced the syllable ut with the syllable do for the first time for the convenience of singing. In England in the 1st half. 19th century S. Glover and J. Curwen created the so-called. “Tonic Sol-fa method” of teaching music. Supporters of this method use relative S. with syllables do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti (doh, ray, me, fah, sol, lah, te) and alphabetic notation with the initial letters of these syllables: d, r, m, f, s, 1, t. An increase in steps is expressed with the vowel i; a decrease with the help of the vowel o at the end of syllables; altered names in notation. written out in full. To determine the tonality, traditions are preserved. letter designations (for example, the mark “Key G” prescribes performance in G-dur or e-moll). First of all, characteristic intonations are mastered in the order corresponding to the modal functions of the steps: 1st stage – steps I, V, III; 2nd — steps II and VII; 3rd – steps IV and VI major; after that, the major scale as a whole, intervals, simple modulations, types of minor, alteration are given. Ch. Curwen’s work “The standard course of lessons and exercises in the Tonic Sol-fa method of teaching music” (1858) is a systematic. choir school. singing. In Germany, A. Hundegger adapted the Tonic Sol-fa method to the features of it. language, giving it a name. “Tonic Do” (1897; natural steps: do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, raised – ending in i, lowered – in and). The method became widespread after World War I (1–1914) (F. Jode in Germany and others). Further development after World War II (18–2) was carried out in the GDR by A. Stir and in Switzerland by R. Schoch. In Germany, the “Union of Tonic Do” works.

In addition to these basic S. systems, in the 16-19 centuries. in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, a number of others have been put forward. Among them – species relates. S. with names of numbers: in Germany – eins, zwei, drei, vier, fünf, sechs, sieb’n (!) (K. Horstig, 1800; B. Natorp, 1813), in France – un, deux, trois, quatr’ (!), cinq, six, sept (G. Boquillon, 1823) without taking into account alters. steps. Among the absolute systems, S. retain the meaning of Clavisieren or Abecedieren, that is, singing with letter designations used in German countries. language from the 16th century. The system of K. Eitz (“Tonwortmethode”, 1891) was distinguished by melodiousness and logic, reflecting both chromaticity, diatonicity, and anharmonism of European. sound system. On the basis of certain principles of Eitz and the Tonic Do method, a new relative S. “YALE” by R. Münnich (1930) was created, which in 1959 was officially recommended in the GDR for use in general education. schools. In Hungary, Z. Kodai adapted the system “Tonic Sol-fa” – “Tonic Do” to pentatonic. Hungarian nature. nar. songs. He and his students E. Adam and D. Kerenyi in 1943-44 published the School Songbook, singing textbooks for general education. schools, methodical a guide for teachers using relative C. (Hungarian syllables: du, rй, mi, fb, szу, lb, ti; the increase in steps is expressed through the ending “i”, the decrease – through the ending “a”.) The development of the system is continued by E Sönyi, Y. Gat, L. Agochi, K. Forrai and others. education on the basis of the Kodaly system in the Hungarian People’s Republic was introduced in all levels of the Nar. education, starting with kindergartens and ending with the Higher Music. school them. F. List. Now, in a number of countries, music is being organized. education based on the principles of Kodály, based on the nat. folklore, with the use of relative S. Institutes named after. Kodai in the USA (Boston, 1969), Japan (Tokyo, 1970), Canada (Ottawa, 1976), Australia (1977), Intern. Kodai Society (Budapest, 1975).

Gvidonova S. penetrated into Russia through Poland and Lithuania along with a five-line notation (songbook “Songs of praise of Boskikh”, compiled by Jan Zaremba, Brest, 1558; J. Lyauksminas, “Ars et praxis musica”, Vilnius, 1667). Nikolai Diletsky’s “Grammar of Musician Singing” (Smolensk, 1677; Moscow, 1679 and 1681, ed. 1910, 1970, 1979) contains circles of fourths and fifths with the movement of the same melodies. revolutions in all major and minor keys. In con. 18th century absolute “natural solfeggio” became known in Russia thanks to the Italian. vocalists and composers-teachers who worked Ch. arr. in St. Petersburg (A. Sapienza, J. and V. Manfredini, etc.), and began to be used in the Pridv. chanter chapel, in the chapel of Count Sheremetev and other serf choirs, in noble uch. institutions (for example, in the Smolny Institute), in private music. schools that arose from the 1770s. But church. songbooks were published in the 19th century. in the “cephout key” (see Key). Since the 1860s absolute S. is cultivated as a compulsory subject in St. Petersburg. and Mosk. conservatories, but refers. S., associated with the digital system Galen – Paris – Sheve, in St. Petersburg. Free music. school and free simple choir classes. singing Moscow. departments of the RMS. Application refers. Music was supported by M. A. Balakirev, G. Ya. Lomakin, V. S. Serova, V. F. Odoevsky, N. G. Rubinshtein, G. A. Larosh, K. K. Albrecht, and others. methodical manuals were published both in five-linear notation and absolute C., and in digital notation and relates. C. Starting from 1905, P. Mironositsky promoted the Tonic Sol-fa method, which he adapted to Russian. language.

In the USSR, for a long time they continued to use exclusively traditional absolute S., however, in the Sov. time, the purpose of S.’s classes, music has changed significantly. material, teaching methods. The goal of S. was not only acquaintance with musical notation, but also the mastery of the laws of music. speeches on the material of Nar. and prof. creativity. By 1964 H. Kalyuste (Est. SSR) developed a system of music. education with the use of relates. S., based on the Kodai system. In view of the fact that the syllables do, re, mi, fa, salt, la, si serve in the USSR to denote the absolute height of sounds, Caljuste delivered a new series of syllabic names. steps of the major mode: JO, LE, MI, NA, SO, RA, DI with the designation of the minor tonic through the syllable RA, the rise of the steps through the ending of syllables into the vowel i, the decrease through the endings into the vowel i. In all est. schools in music lessons uses refers. S. (according to the textbooks of H. Kaljuste and R. Päts). In Latv. The SSR has done similar work (authors of textbooks and manuals on C are A. Eidins, E. Silins, A. Krumins). Experiences of application relates. S. with the syllables Yo, LE, VI, NA, 30, RA, TI are held in the RSFSR, Belarus, Ukraine, Armenia, Georgia, Lithuania, and Moldova. The purpose of these experiments is to develop more effective methods for the development of muses. hearing, the best development of folk-song culture of each nationality, raising the level of music. literacy of students.

2) Under the term “S.” sometimes they understand reading notes without intonation, in contrast to the term “solfeggio” – singing sounds with the corresponding names (for the first time by K. Albrecht in the book “Course of Solfeggio”, 1880). Such an interpretation is arbitrary, not corresponding to any historical. meaning, nor modern intl. use of the term “C”.

References: Albrecht K. K., Guide to choral singing according to the Sheve digital method, M., 1868; Miropolsky S., On the musical education of the people in Russia and Western Europe, St. Petersburg, 1881, 1910; Diletsky Nikolai, Musician Grammar, St. Petersburg, 1910; Livanova T. N., History of Western European music until 1789, M.-L., 1940; Apraksina O., Musical education in the Russian secondary school, M.-L., 1948; Odoevsky V.P., Free class of simple choral singing of the RMS in Moscow, Den, 1864, No 46, the same, in his book. Musical and literary heritage, M., 1956; his own, ABC music, (1861), ibid.; his, Letter to V. S. Serova dated 11 I 1864, ibid.; Lokshin D. L., Choral singing in the Russian pre-revolutionary and Soviet school, M., 1957; Weiss R., Absolute and relative solmization, in the book: Questions of the method of educating hearing, L., 1967; Maillart R., Les tons, ou Discours sur les modes de musique…, Tournai, 1610; Solfèges pour servir a l’tude dans le Conservatoire de Musique a Pans, par les Citoyens Agus, Catel, Cherubini, Gossec, Langlé, Martini, Méhul et Rey, R., An X (1802); Chevé E., Paris N., Méthode élémentaire de musique vocale, R., 1844; Glover SA, A manual of the Norwich sol-fa system, 1845; Сurwen J., The standard course of lessons and exercises m the tonic sol-fa method of teaching music, L., 1858; Hundoegger A., Leitfaden der Tonika Do-Lehre, Hannover, 1897; Lange G., Zur Geschichte der Solmisation, “SIMG”, Bd 1, B., 1899-1900; Kodaly Z., Iskolai nekgyjtemny, köt 1-2, Bdpst, 1943; his own, Visszatekintйs, köt 1-2, Bdpst, 1964; Adam J., Mudszeres nektanitbs, Bdpst, 1944; Szцnyi E., Azenei нrвs-olvasбs mуdszertana, kцt. 1-3, Bdpst, 1954; S’ndor F., Zenei nevel’s Magyarorsz’gon, Bdpst, 1964; Stier A., Methodik der Musikerziehung. Nach den Grundsätzen der Tonika Do-Lehre, Lpz., 1958; Handbuch der Musikerziehung, Tl 1-3, Lpz., 1968-69.

P. F. Weiss