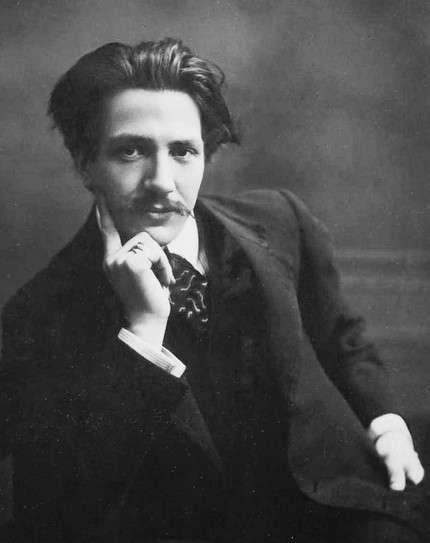

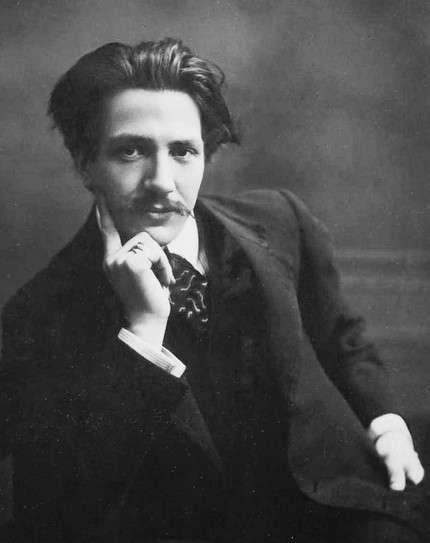

Jacques Thibaud |

Jacques Thibaud

On September 1, 1953, the music world was shocked by the news that on the way to Japan, Jacques Thibault, one of the most outstanding violinists of the XNUMXth century, the recognized head of the French violin school, died as a result of a plane crash near Mount Semet near Barcelona.

Thibaut was a true Frenchman, and if one can imagine the most ideal expression of French violin art, then it was embodied precisely in him, his playing, artistic appearance, a special warehouse of his artistic personality. Jean-Pierre Dorian wrote in a book about Thibaut: “Kreisler once told me that Thibault was the greatest violinist in the world. Undoubtedly, he was the greatest violinist in France, and when he played, it seemed that you heard a part of France itself singing.

“Thibaut was not only an inspired artist. He was a crystal-clearly honest man, lively, witty, charming – a real Frenchman. His performance, imbued with sincere cordiality, optimistic in the best sense of the word, was born under the fingers of a musician who experienced the joy of creative creation in direct communication with the audience. — This is how David Oistrakh responded to Thibault’s death.

Anyone who happened to hear the violin works of Saint-Saens, Lalo, Franck performed by Thibault will never forget this. With capricious grace he sounded the finale of Lalo’s Spanish symphony; with amazing plasticity, chased completeness of each phrase, he conveyed the intoxicating melodies of Saint-Saens; sublimely beautiful, spiritually humanized appeared before the listener Franck’s Sonata.

“His interpretation of the classics was not constrained by the framework of dry academicism, and the performance of French music was inimitable. He revealed in a new way such works as the Third Concerto, Rondo Capriccioso and Havanaise by Saint-Saens, Lalo’s Spanish Symphony, Chausson’s Poem, Fauré and Franck’s sonatas, etc. His interpretations of these works became a model for subsequent generations of violinists.

Thibault was born on September 27, 1881 in Bordeaux. His father, an excellent violinist, worked in an opera orchestra. But even before the birth of Jacques, his father’s violin career ended due to atrophy of the fourth finger of his left hand. There was nothing else to do but to study pedagogy, and not only violin, but also piano. Surprisingly, he mastered both spheres of musical and pedagogical art quite successfully. In any case, he was greatly appreciated in the city. Jacques did not remember his mother, since she died when he was only a year and a half old.

Jacques was the seventh son in the family and the youngest. One of his brothers died at 2 years old, the other at 6. The survivors were distinguished by great musicality. Alphonse Thibaut, an excellent pianist, received the first prize from the Paris Conservatory at the age of 12. For many years he was a prominent musical figure in Argentina, where he arrived shortly after completing his education. Joseph Thibaut, pianist, became professor at the conservatory in Bordeaux; he studied with Louis Diemer in Paris, Cortot found phenomenal data from him. The third brother, Francis, is a cellist and subsequently served as director of the conservatory in Oran. Hippolyte, a violinist, a student of Massard, who unfortunately died early from consumption, was exceptionally gifted.

Ironically, Jacques’ father initially (when he was 5 years old) began to teach the piano, and Joseph the violin. But soon the roles changed. After the death of Hippolyte, Jacques asked his father for permission to switch to the violin, which attracted him much more than the piano.

The family often played music. Jacques recalled the quartet evenings, where the parts of all instruments were performed by the brothers. Once, shortly before Hippolyte’s death, they played Schubert’s b-moll trio, the future masterpiece of the Thibaut-Cortot-Casals ensemble. The book of memoirs “Un violon parle” points to the extraordinary love of little Jacques for the music of Mozart, it is also repeatedly said that his “horse”, which aroused the constant admiration of the audience, was the Romance (F) of Beethoven. All this is very indicative of Thibaut’s artistic personality. The harmonious nature of the violinist was naturally impressed by Mozart with the clarity, refinement of style, and the soft lyricism of his art.

Thibaut remained all his life far from anything disharmonious in art; rough dynamics, expressionistic excitement and nervousness disgusted him. His performance invariably remained clear, humane and spiritual. Hence the attraction to Schubert, later to Frank, and from the legacy of Beethoven – to his most lyrical works – romances for the violin, in which an elevated ethical atmosphere prevails, while the “heroic” Beethoven was more difficult. If we develop further the definition of Thibault’s artistic image, we will have to admit that he was not a philosopher in music, he did not impress with the performance of Bach’s works, the dramatic tension of Brahms’ art was alien to him. But in Schubert, Mozart, Lalo’s Spanish Symphony and Franck’s Sonata, the amazing spiritual richness and refined intellect of this inimitable artist were revealed with the utmost completeness. His aesthetic orientation began to be determined already at an early age, in which, of course, the artistic atmosphere that reigned in his father’s house played a huge role.

At the age of 11, Thibault made his first public appearance. The success was such that his father took him from Bordeaux to Angers, where, after the performance of the young violinist, all music lovers enthusiastically spoke about him. Returning to Bordeaux, his father assigned Jacques to one of the city’s orchestras. Just at this time, Eugene Ysaye arrived here. After listening to the boy, he was struck by the freshness and originality of his talent. “He needs to be taught,” Izai told his father. And the Belgian made such an impression on Jacques that he began to beg his father to send him to Brussels, where Ysaye taught at the conservatory. However, the father objected, as he had already negotiated about his son with Martin Marsik, a professor at the Paris Conservatory. And yet, as Thibault himself later pointed out, Izai played a huge role in his artistic formation and he took over a lot of valuable things from him. Having already become a major artist, Thibault maintained constant contact with Izaya, often visited his villa in Belgium and was a constant partner in ensembles with Kreisler and Casals.

In 1893, when Jacques was 13 years old, he was sent to Paris. At the station, his father and brothers saw him off, and on the train, a compassionate lady took care of him, worried that the boy was traveling alone. In Paris, Thibault was waiting for his father’s brother, a dashing factory worker who built military ships. Uncle’s dwelling in the Faubourg Saint-Denis, his daily routine and the atmosphere of joyless work oppressed Jacques. Having migrated from his uncle, he rented a little room on the fifth floor on Rue Ramey, in Montmartre.

The day after his arrival in Paris, he went to the conservatory to Marsik and was accepted into his class. When asked by Marsik which of the composers Jacques loves the most, the young musician answered without hesitation – Mozart.

Thibaut studied in Marsik’s class for 3 years. He was an illustrious teacher who trained Carl Flesch, George Enescu, Valerio Franchetti and other remarkable violinists. Thibaut treated the teacher with reverence.

During his studies at the conservatory, he lived very poorly. The father could not send enough money – the family was large, and the earnings were modest. Jacques had to earn extra money by playing in small orchestras: in the cafe Rouge in the Latin Quarter, the orchestra of the Variety Theater. Subsequently, he admitted that he did not regret this harsh school of his youth and 180 performances with the Variety orchestra, where he played at the second violin console. He did not regret life in the attic of the Rue Ramey, where he lived with two conservatives, Jacques Capdeville and his brother Felix. They were sometimes joined by Charles Mancier, and they spent whole evenings playing music.

Thibaut graduated from the conservatory in 1896, winning first prize and a gold medal. His career in Parisian musical circles is then consolidated with solo performances in concerts at the Chatelet, and in 1898 with the orchestra of Edouard Colonne. From now on, he is the favorite of Paris, and the performances of the Variety Theater are forever behind. Enescu left us the brightest lines about the impression that Thibault’s game caused during this period among the listeners.

“He studied before me,” writes Enescu, “with Marsik. I was fifteen years old when I first heard it; To be honest, it took my breath away. I was beside myself with delight. It was so new, unusual!. The conquered Paris called him the Prince Charming and was fascinated by him, like a woman in love. Thibault was the first of the violinists to reveal to the public a completely new sound – the result of the complete unity of the hand and the stretched string. His playing was surprisingly tender and passionate. Compared to him, Sarasate is cold perfection. According to Viardot, this is a mechanical nightingale, while Thibaut, especially in high spirits, was a living nightingale.

At the beginning of the 1901th century, Thibault went to Brussels, where he performed in symphony concerts; Izai conducts. Here began their great friendship, which lasted until the death of the great Belgian violinist. From Brussels, Thibaut went to Berlin, where he met Joachim, and in December 29 he came to Russia for the first time to participate in a concert dedicated to the music of French composers. He performs with pianist L. Würmser and conductor A. Bruno. The concert, which took place on December 1902 in St. Petersburg, was a great success. With no less success, Thibaut gives concerts at the beginning of XNUMX in Moscow. His chamber evening with cellist A. Brandukov and pianist Mazurina, whose program included the Tchaikovsky Trio, delighted N. Kashkin: , and secondly, by the strict and intelligent musicality of his performance. The young artist eschews any specially virtuoso affectation, but he knows how to take everything possible from the composition. For example, we have not heard from anyone the Rondo Capriccioso played with such grace and brilliance, although it was at the same time impeccable in terms of the severity of the character of the performance.

In 1903, Thibault made his first trip to the United States and often gave concerts in England during this period. Initially, he played the violin by Carlo Bergonzi, later on the wonderful Stradivarius, which once belonged to the outstanding French violinist of the early XNUMXth century P. Baio.

When in January 1906 Thibaut was invited by A. Siloti to St. Petersburg for concerts, he was described as an amazingly talented violinist who showed both perfect technique and wonderful melodiousness of the bow. On this visit, Thibault completely conquered the Russian public.

Thibaut was in Russia before the First World War two more times – in October 1911 and in the 1912/13 season. In the 1911 concerts he performed Mozart’s Concerto in E flat major, Lalo’s Spanish symphony, Beethoven’s and Saint-Saens sonatas. Thibault gave a sonata evening with Siloti.

In the Russian Musical Newspaper they wrote about him: “Thibault is an artist of high merits, high flight. Brilliance, power, lyricism – these are the main features of his game: “Prelude et Allegro” by Punyani, “Rondo” by Saint-Saens, played, or rather sung, with remarkable ease, grace. Thibaut is more of a first-class soloist than a chamber performer, although the Beethoven sonata he played with Siloti went flawlessly.

The last remark is surprising, because the existence of the famous trio, founded by him in 1905 with Cortot and Casals, is connected with the name of Thibaut. Casals recalled this trio many years later with warm warmth. In a conversation with Corredor, he said that the ensemble began to work a few years before the war of 1914 and its members were united by fraternal friendship. “It was from this friendship that our trio was born. How many trips to Europe! How much joy we got from friendship and music!” And further: “We performed Schubert’s B-flat trio most often. In addition, the trio of Haydn, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Schumann and Ravel appeared in our repertoire.”

Before the First World War, another Thibault trip to Russia was planned. Concerts were scheduled for November 1914. The outbreak of war prevented the implementation of Thibault’s intentions.

During the First World War, Thibaut was drafted into the army. He fought on the Marne near Verdun, was wounded in the hand and almost lost the opportunity to play. However, fate turned out to be favorable – he saved not only his life, but also his profession. In 1916, Thibaut was demobilized and soon took an active part in the large “National Matinees”. In 1916, Henri Casadesus, in a letter to Siloti, lists the names of Capet, Cortot, Evitte, Thibaut and Riesler and writes: “We look to the future with deep faith and want, even in our wartime, to contribute to the rise of our art.”

The end of the war coincided with the master’s years of maturity. He is a recognized authority, the head of French violin art. In 1920, together with pianist Marguerite Long, he founded the Ecole Normal de Musique, a higher musical school in Paris.

The year 1935 was marked by great joy for Thibault – his student Ginette Neve won first prize at the Henryk Wieniawski International Competition in Warsaw, defeating such formidable rivals as David Oistrakh and Boris Goldstein.

In April 1936, Thibaut arrived in the Soviet Union with Cortot. The largest musicians responded to his performances – G. Neuhaus, L. Zeitlin and others. G. Neuhaus wrote: “Thibaut plays the violin to perfection. Not a single reproach can be thrown at his violin technique. Thibault is “sweet-sounding” in the best sense of the word, he never falls into sentimentality and sweetness. The sonatas of Gabriel Fauré and Caesar Franck, performed by him together with Cortot, were, from this point of view, especially interesting. Thibaut is graceful, his violin sings; Thibault is a romantic, the sound of his violin is unusually soft, his temperament is genuine, real, infectious; the sincerity of Thibaut’s performance, the charm of his peculiar manner, captivate the listener forever … “

Neuhaus unconditionally ranks Thibaut among the romantics, without explaining specifically what he feels his romanticism is. If this refers to the originality of his performing style, illuminated by sincerity, cordiality, then one can fully agree with such a judgment. Only Thibault’s romanticism is not “Listovian”, and even more so not “Pagannian”, but “Frankish”, coming from the spirituality and sublimity of Cesar Franck. His romance was in many ways consonant with Izaya’s romance, only much more refined and intellectualized.

During his stay in Moscow in 1936, Thibaut became extremely interested in the Soviet violin school. He called our capital “the city of violinists” and expressed his admiration for the playing of the then young Boris Goldstein, Marina Kozolupova, Galina Barinova and others. “the soul of performance”, and which is so unlike our Western European reality”, and this is so characteristic of Thibaut, for whom the “soul of performance” has always been the main thing in art.

The attention of Soviet critics was attracted by the playing style of the French violinist, his violin techniques. I. Yampolsky recorded them in his article. He writes that when Thibaut played, he was characterized by: mobility of the body associated with emotional experiences, a low and flat holding of the violin, a high elbow in the setting of the right hand and a sheer hold of the bow with fingers that are extremely mobile on a cane. Thiebaud played with small pieces of the bow, a dense detail, often used at the stock; I used the first position and open strings a lot.

Thibaut perceived World War II as a mockery of humanity and a threat to civilization. Fascism with its barbarism was organically alien to Thibaut, the heir and custodian of the traditions of the most refined of European musical cultures – French culture. Marguerite Long recalls that at the beginning of the war, she and Thibaut, the cellist Pierre Fournier and the concertmaster of the Grand Opera Orchestra Maurice Villot were preparing Fauré’s piano quartet for performance, a composition written in 1886 and never performed. The quartet was supposed to be recorded on a gramophone record. The recording was scheduled for June 10, 1940, but in the morning the Germans entered Holland.

“Shaken, we went into the studio,” Long recalls. – I felt the longing that gripped Thibault: his son Roger fought on the front line. During the war, our excitement reached its apogee. It seems to me that the record reflected this correctly and sensitively. The next day, Roger Thibault died a heroic death.”

During the war, Thibaut, together with Marguerite Long, remained in occupied Paris, and here in 1943 they organized the French National Piano and Violin Competition. Competitions that became traditional after the war were later named after them.

However, the first of the competitions, held in Paris in the third year of the German occupation, was a truly heroic act and had great moral significance for the French. In 1943, when it seemed that the living forces of France were paralyzed, two French artists decided to show that the soul of a wounded France was invincible. Despite the difficulties, seemingly insurmountable, armed only with faith, Marguerite Long and Jacques Thibault founded a national competition.

And the difficulties were terrible. Judging by the story of Long, transmitted in the book by S. Khentova, it was necessary to lull the vigilance of the Nazis, presenting the competition as a harmless cultural undertaking; it was necessary to get the money, which in the end was provided by the Pate-Macconi record company, which took over the organizational chores, as well as subsidizing part of the prizes. In June 1943, the competition finally took place. Its winners were pianist Samson Francois and violinist Michel Auclair.

The next competition took place after the war, in 1946. The government of France took part in its organization. The competitions have become a national and major international phenomenon. Hundreds of violinists from around the world participated in the five competitions, which took place from the moment they were founded until the death of Thibaut.

In 1949, Thibaut was shocked by the death of his beloved student Ginette Neve, who died in a plane crash. At the next competition, a prize was given in her name. In general, personalized prizes have become one of the traditions of the Paris competitions – the Maurice Ravel Memorial Prize, the Yehudi Menuhin Prize (1951).

In the post-war period, the activities of the music school, founded by Marguerite Long and Jacques Thibault, intensified. The reasons that led them to create this institution were dissatisfaction with the staging of music education at the Paris Conservatoire.

In the 40s, the School had two classes – the piano class, led by Long, and the violin class, by Jacques Thibault. They were assisted by their students. The principles of the School – strict discipline in work, a thorough analysis of one’s own game, the lack of regulation in the repertoire in order to freely develop the individuality of students, but most importantly – the opportunity to study with such outstanding artists attracted many students to the School. Pupils of the School were introduced, in addition to classical works, to all the major phenomena of modern musical literature. In Thibaut’s class, the works of Honegger, Orik, Milhaud, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Kabalevsky and others were learned.

Thibaut’s increasingly unfolding pedagogical activity was interrupted by a tragic death. He passed away full of enormous and still far from exhausted energy. The competitions he founded and the School remain an undying memory of him. But for those who knew him personally, he will still remain a Man with a capital letter, charmingly simple, cordial, kind, incorruptibly honest and objective in his judgments about other artists, sublimely pure in his artistic ideals.

L. Raaben