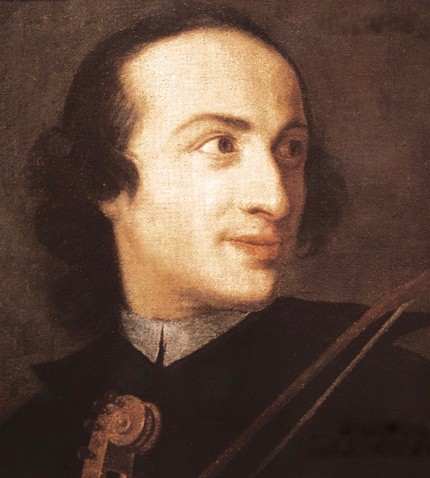

Giuseppe Tartini (Giuseppe Tartini) |

Giuseppe Tartini

Tartini. Sonata g-moll, “Devil’s Trills” →

Giuseppe Tartini is one of the luminaries of the Italian violin school of the XNUMXth century, whose art has retained its artistic significance to this day. D. Oistrakh

The outstanding Italian composer, teacher, virtuoso violinist and musical theorist G. Tartini occupied one of the most important places in the violin culture of Italy in the first half of the XNUMXth century. Traditions coming from A. Corelli, A. Vivaldi, F. Veracini and other great predecessors and contemporaries merged in his art.

Tartini was born into a family belonging to the noble class. Parents intended their son to the career of a clergyman. Therefore, he first studied at the parish school in Pirano, and then in Capo d’Istria. There Tartini began to play the violin.

The life of a musician is divided into 2 sharply opposite periods. Windy, intemperate by nature, looking for dangers – such is he in his youthful years. Tartini’s self-will forced his parents to give up the idea of sending their son on a spiritual path. He goes to Padua to study law. But Tartini also prefers fencing to them, dreaming of the activity of a fencing master. In parallel with fencing, he continues to more and more purposefully engage in music.

A secret marriage to his student, the niece of a major clergyman, dramatically changed all of Tartini’s plans. The marriage aroused the indignation of the aristocratic relatives of his wife, Tartini was persecuted by Cardinal Cornaro and was forced to hide. His refuge was the Minorite monastery in Assisi.

From that moment began the second period of Tartini’s life. The monastery not only sheltered the young rake and became his haven during the years of exile. It was here that Tartini’s moral and spiritual rebirth took place, and here his true development as a composer began. In the monastery, he studied music theory and composition under the guidance of the Czech composer and theorist B. Chernogorsky; independently studied the violin, reaching true perfection in mastering the instrument, which, according to contemporaries, even surpassed the game of the famous Corelli.

Tartini stayed in the monastery for 2 years, then for another 2 years he played at the opera house in Ancona. There the musician met with Veracini, who had a significant influence on his work.

Tartini’s exile ended in 1716. From that time until the end of his life, with the exception of short breaks, he lived in Padua, leading the chapel orchestra in the Basilica of St. Antonio and performing as a violin soloist in various cities of Italy. In 1723, Tartini received an invitation to visit Prague to take part in musical celebrations on the occasion of the coronation of Charles VI. This visit, however, lasted until 1726: Tartini accepted the offer to take the position of a chamber musician in the Prague chapel of Count F. Kinsky.

Returning to Padua (1727), the composer organized a musical academy there, devoting much of his energy to teaching. Contemporaries called him “teacher of nations.” Among the students of Tartini are such outstanding violinists of the XNUMXth century as P. Nardini, G. Pugnani, D. Ferrari, I. Naumann, P. Lausse, F. Rust and others.

The musician’s contribution to the further development of the art of playing the violin is great. He changed the design of the bow, lengthening it. The skill of conducting the bow of Tartini himself, his extraordinary singing on the violin began to be considered exemplary. The composer has created a huge number of works. Among them are numerous trio sonatas, about 125 concertos, 175 sonatas for violin and cembalo. It was in Tartini’s work that the latter received further genre and stylistic development.

The vivid imagery of the composer’s musical thinking manifested itself in the desire to give programmatic subtitles to his works. The sonatas “Abandoned Dido” and “The Devil’s Trill” gained particular fame. The last remarkable Russian music critic V. Odoevsky considered the beginning of a new era in violin art. Along with these works, the monumental cycle “The Art of the Bow” is of great importance. Consisting of 50 variations on the theme of Corelli’s gavotte, it is a kind of set of techniques that has not only pedagogical significance, but also high artistic value. Tartini was one of the inquisitive musician-thinkers of the XNUMXth century, his theoretical views found expression not only in various treatises on music, but also in correspondence with major musical scientists of that time, being the most valuable documents of his era.

I. Vetlitsyna

Tartini is an outstanding violinist, teacher, scholar and deep, original, original composer; this figure is still far from being appreciated for its merits and significance in the history of music. It is possible that he will still be “discovered” for our era and his creations, most of which are gathering dust in the annals of Italian museums, will be revived. Now, only students play 2-3 of his sonatas, and in the repertoire of major performers, his famous works – “Devil’s Trills”, sonatas in A minor and G minor occasionally flash by. His wonderful concerts remain unknown, some of which could well take their rightful place next to the concerts of Vivaldi and Bach.

In the violin culture of Italy in the first half of the XNUMXth century, Tartini occupied a central place, as if synthesizing the main stylistic trends of his time in performance and creativity. His art absorbed, merging into a monolithic style, the traditions coming from Corelli, Vivaldi, Locatelli, Veracini, Geminiani and other great predecessors and contemporaries. It impresses with its versatility – the most tender lyrics in the “Abandoned Dido” (that was the name of one of the violin sonatas), the hot temperament of the melos in the “Devil’s Trills”, the brilliant concert performance in the A-dur fugue, the majestic sorrow in the slow Adagio, still retaining the pathetic declamatory the style of the masters of the musical baroque era.

There is a lot of romanticism in the music and appearance of Tartini: “His artistic nature. indomitable passionate impulses and dreams, throwing and struggles, rapid ups and downs of emotional states, in a word, everything that Tartini did, together with Antonio Vivaldi, one of the earliest forerunners of romanticism in Italian music, were characteristic. Tartini was distinguished by an attraction to programming, so characteristic of the romantics, a great love for Petrarch, the most lyrical singer of love of the Renaissance. “It is no coincidence that Tartini, the most popular among violin sonatas, has already received the completely romantic name “Devil’s Trills”.”

Tartini’s life is divided into two sharply opposite periods. The first is the youthful years before seclusion in the monastery of Assisi, the second is the rest of life. Windy, playful, hot, intemperate by nature, looking for dangers, strong, dexterous, courageous – such is he in the first period of his life. In the second, after a two-year stay in Assisi, this is a new person: restrained, withdrawn, sometimes gloomy, always concentrating on something, observant, inquisitive, intensively working, already calmed down in his personal life, but all the more tirelessly searching in the field of art , where the pulse of his naturally hot nature continues to beat.

Giuseppe Tartini was born on April 12, 1692 in Pirano, a small town located in Istria, an area bordering present-day Yugoslavia. Many Slavs lived in Istria, it “seethed with uprisings of the poor – small peasants, fishermen, artisans, especially from the lower classes of the Slavic population – against English and Italian oppression. Passions were seething. The proximity of Venice introduced the local culture to the ideas of the Renaissance, and later to that artistic progress, the stronghold of which the anti-papist republic remained in the XNUMXth century.

There is no reason to classify Tartini among the Slavs, however, according to some data from foreign researchers, in ancient times his surname had a purely Yugoslav ending – Tartich.

Giuseppe’s father – Giovanni Antonio, a merchant, a Florentine by birth, belonged to the “nobile”, that is, the “noble” class. Mother – nee Catarina Giangrandi from Pirano, apparently, was from the same environment. His parents intended his son for a spiritual career. He was to become a Franciscan monk in the Minorite monastery, and studied first at the parish school in Pirano, then at Capo d’Istria, where music was taught at the same time, but in the most elementary form. Here the young Giuseppe began to play the violin. Who exactly was his teacher is unknown. It could hardly be a major musician. And later, Tartini did not have to learn from a professionally strong violinist teacher. His skill was entirely conquered by himself. Tartini was in the true sense of the word self-taught (autodidact).

The self-will, ardor of the boy forced the parents to abandon the idea of directing Giuseppe along the spiritual path. It was decided that he would go to Padua to study law. In Padua was the famous University, where Tartini entered in 1710.

He treated his studies “slipshod” and preferred to lead a stormy, frivolous life, replete with all sorts of adventures. He preferred fencing to jurisprudence. The possession of this art was prescribed for every young man of “noble” origin, but for Tartini it became a profession. He participated in many duels and achieved such skill in fencing that he was already dreaming of the activity of a swordsman, when suddenly one circumstance suddenly changed his plans. The fact is that in addition to fencing, he continued to study music and even gave music lessons, working on the meager funds sent to him by his parents.

Among his students was Elizabeth Premazzone, niece of the all-powerful Archbishop of Padua, Giorgio Cornaro. An ardent young man fell in love with his young student and they secretly got married. When the marriage became known, it did not delight the aristocratic relatives of his wife. Cardinal Cornaro was especially angry. And Tartini was persecuted by him.

Disguised as a pilgrim so as not to be recognized, Tartini fled from Padua and headed for Rome. However, after wandering for some time, he stopped at a Minorite monastery in Assisi. The monastery sheltered the young rake, but radically changed his life. Time flowed in a measured sequence, filled with either a church service or music. So thanks to a random circumstance, Tartini became a musician.

In Assisi, fortunately for him, lived Padre Boemo, a famous organist, church composer and theorist, a Czech by nationality, before being tonsured a monk, who bore the name of Bohuslav of Montenegro. In Padua he was director of the choir at the Cathedral of Sant’Antonio. Later, in Prague, K.-V. glitch. Under the guidance of such a wonderful musician, Tartini began to develop rapidly, comprehending the art of counterpoint. However, he became interested not only in musical science, but also in the violin, and was soon able to play during services to the accompaniment of Padre Boemo. It is possible that it was this teacher who developed in Tartini the desire for research in the field of music.

A long stay in the monastery left a mark on the character of Tartini. He became religious, inclined towards mysticism. However, his views did not affect his work; Tartini’s works prove that inwardly he remained an ardent, spontaneous worldly person.

Tartini lived in Assisi for more than two years. He returned to Padua due to a random circumstance, which A. Giller told about: “When he once played the violin in the choirs during a holiday, a strong gust of wind lifted the curtain in front of the orchestra. so that the people who were in the church saw him. One Padua, who was among the visitors, recognized him and, returning home, betrayed the whereabouts of Tartini. This news was immediately learned by his wife, as well as the cardinal. Their anger subsided during this time.

Tartini returned to Padua and soon became known as a talented musician. In 1716, he was invited to participate in the Academy of Music, a solemn celebration in Venice in the palace of Donna Pisano Mocenigo in honor of the Prince of Saxony. In addition to Tartini, the performance of the famous violinist Francesco Veracini was expected.

Veracini enjoyed worldwide fame. The Italians called his playing style “completely new” because of the subtlety of emotional nuances. It was really new compared to the majestic pathetic style of play that prevailed in Corelli’s time. Veracini was the forerunner of the “preromantic” sensibility. Tartini had to face such a dangerous opponent.

Hearing Veracini play, Tartini was shocked. Refusing to speak, he sent his wife to his brother in Pirano, and he himself left Venice and settled in a monastery in Ancona. In seclusion, away from the bustle and temptations, he decided to achieve the mastery of Veracini through intensive studies. He lived in Ancona for 4 years. It was here that a deep, brilliant violinist was formed, whom the Italians called “II maestro del la Nazioni” (“World Maestro”), emphasizing his unsurpassedness. Tartini returned to Padua in 1721.

Tartini’s subsequent life was spent mainly in Padua, where he worked as a violin soloist and accompanist of the chapel of the temple of Sant’Antonio. This chapel consisted of 16 singers and 24 instrumentalists and was considered one of the best in Italy.

Only once did Tartini spend three years outside Padua. In 1723 he was invited to Prague for the coronation of Charles VI. There he was heard by a great music lover, philanthropist Count Kinsky, and persuaded him to stay in his service. Tartini worked in the Kinsky chapel until 1726, then homesickness forced him to return. He did not leave Padua again, although he was repeatedly called to his place by high-ranking music lovers. It is known that Count Middleton offered him £3000 a year, at that time a fabulous sum, but Tartini invariably rejected all such offers.

Having settled in Padua, Tartini opened here in 1728 the High School of Violin Playing. The most prominent violinists of France, England, Germany, Italy flocked to it, eager to study with the illustrious maestro. Nardini, Pasqualino Vini, Albergi, Domenico Ferrari, Carminati, the famous violinist Sirmen Lombardini, the Frenchmen Pazhen and Lagusset and many others studied with him.

In everyday life, Tartini was a very modest person. De Brosse writes: “Tartini is polite, amiable, without arrogance and whims; he talks like an angel and without prejudice about the merits of French and Italian music. I was very pleased with both his acting and his conversation.”

His letter (March 31, 1731) to the famous musician-scientist Padre Martini has been preserved, from which it is clear how critical he was to the assessment of his treatise on combinational tone, considering it exaggerated. This letter testifies to the extreme modesty of Tartini: “I cannot agree to be presented before scientists and exquisitely intelligent people as a person with pretensions, full of discoveries and improvements in the style of modern music. God save me from this, I only try to learn from others!

“Tartini was very kind, helped the poor a lot, worked for free with gifted children of the poor. In family life, he was very unhappy, due to the intolerably bad character of his wife. Those who knew the Tartini family claimed that she was the real Xanthippe, and he was kind like Socrates. These circumstances of family life further contributed to the fact that he completely went into art. Until a very old age, he played in the Basilica of Sant’Antonio. They say that the maestro, already at a very advanced age, went every Sunday to the cathedral in Padua to play the Adagio from his sonata “The Emperor”.

Tartini lived to the age of 78 and died of scurbut or cancer in 1770 in the arms of his favorite student, Pietro Nardini.

Several reviews have been preserved about the game of Tartini, moreover, containing some contradictions. In 1723 he was heard in the chapel of Count Kinsky by the famous German flutist and theorist Quantz. Here is what he wrote: “During my stay in Prague, I also heard the famous Italian violinist Tartini, who was in the service there. He was truly one of the greatest violinists. He produced a very beautiful sound from his instrument. His fingers and his bow were equally subject to him. He performed the greatest difficulties effortlessly. A trill, even a double one, he beat with all fingers equally well and played willingly in high positions. However, his performance was not touching and his taste was not noble and often clashed with a good manner of singing.

This review can be explained by the fact that after Ancona Tartini, apparently, was still at the mercy of technical problems, worked for a long time to improve his performing apparatus.

In any case, other reviews say otherwise. Grosley, for example, wrote that Tartini’s game did not have brilliance, he could not stand it. When Italian violinists came to show him their technique, he listened coldly and said: “It’s brilliant, it’s alive, it’s very strong, but,” he added, raising his hand to his heart, “it didn’t tell me anything.”

An exceptionally high opinion of Tartini’s playing was expressed by Viotti, and the authors of the violin Methodology of the Paris Conservatory (1802) Bayot, Rode, Kreutzer noted harmony, tenderness, and grace among the distinctive qualities of his playing.

Of the creative heritage of Tartini, only a small part received fame. According to far from complete data, he wrote 140 violin concertos accompanied by a quartet or string quintet, 20 concerto grosso, 150 sonatas, 50 trios; 60 sonatas have been published, about 200 compositions remain in the archives of the chapel of St. Antonio in Padua.

Among the sonatas are the famous “Devil’s Trills”. There is a legend about her, allegedly told by Tartini himself. “One night (it was in 1713) I dreamed that I had sold my soul to the devil and that he was in my service. Everything was done at my behest – my new servant anticipated my every desire. Once the thought occurred to me to give him my violin and see if he could play something good. But what was my surprise when I heard an extraordinary and charming sonata and played so excellently and skillfully that even the most daring imagination could not imagine anything like it. I was so carried away, delighted and fascinated that it took my breath away. I woke up from this great experience and grabbed the violin to keep at least some of the sounds I heard, but in vain. The sonata I then composed, which I called the “Devil’s Sonata”, is my best work, but the difference from the one that brought me such delight is so great that if I could only deprive myself of the pleasure that the violin gives me, I immediately I would have broken my instrument and gone away from music forever.

I would like to believe in this legend, if not for the date – 1713 (!). To write such a mature essay in Ancona, at the age of 21?! It remains to be assumed that either the date is confused, or the whole story belongs to the number of anecdotes. The autograph of the sonata has been lost. It was first published in 1793 by Jean-Baptiste Cartier in the collection The Art of the Violin, with a summary of the legend and a note from the publisher: “This piece is extremely rare, I owe it to Bayo. The admiration of the latter for the beautiful creations of Tartini convinced him to donate this sonata to me.

In terms of style, Tartini’s compositions are, as it were, a link between pre-classical (or rather “pre-classical”) forms of music and early classicism. He lived in a transitional time, at the junction of two eras, and seemed to close the evolution of Italian violin art that preceded the era of classicism. Some of his compositions have programmatic subtitles, and the absence of autographs introduces a fair amount of confusion into their definition. Thus, Moser believes that “The Abandoned Dido” is a sonata Op. 1 No. 10, where Zellner, the first editor, included Largo from the sonata in E minor (Op. 1 No. 5), transposing it into G minor. The French researcher Charles Bouvet claims that Tartini himself, wanting to emphasize the connection between the sonatas in E minor, called “Abandoned Dido”, and G major, gave the latter the name “Inconsolable Dido”, placing the same Largo in both.

Until the middle of the 50th century, XNUMX variations on the theme of Corelli, called by Tartini “The Art of the Bow”, were very famous. This work had a predominantly pedagogical purpose, although in the edition of Fritz Kreisler, who extracted several variations, they became concert.

Tartini wrote several theoretical works. Among them is the Treatise on Jewelry, in which he tried to comprehend the artistic significance of the melismas characteristic of his contemporary art; “Treatise on Music”, containing research in the field of acoustics of the violin. He devoted his last years to a six-volume work on the study of the nature of musical sound. The work was bequeathed to the Padua professor Colombo for editing and publication, but disappeared. So far, it has not been found anywhere.

Among the pedagogical works of Tartini, one document is of the utmost importance – a letter-lesson to his former student Magdalena Sirmen-Lombardini, in which he gives a number of valuable instructions on how to work on the violin.

Tartini introduced some improvements to the design of the violin bow. A true heir to the traditions of Italian violin art, he attached exceptional importance to the cantilena – “singing” on the violin. It is with the desire to enrich the cantilena that Tartini’s lengthening of the bow is connected. At the same time, for the convenience of holding, he made longitudinal grooves on the cane (the so-called “fluting”). Subsequently, fluting was replaced by winding. At the same time, the “gallant” style that developed in the Tartini era required the development of small, light strokes of a graceful, dance character. For their performance, Tartini recommended a shortened bow.

A musician-artist, an inquisitive thinker, a great teacher – the creator of a school of violinists who spread his fame to all the countries of Europe at that time – such was Tartini. The universality of his nature involuntarily brings to mind the figures of the Renaissance, of which he was the true heir.

L. Raaben, 1967