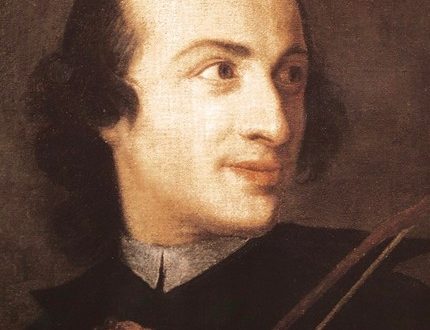

Gaetano Pugnani |

Gaetano Pugnani

At the beginning of the XNUMXth century, Fritz Kreisler published a series of classical plays, among them Pugnani’s Prelude and Allegro. Subsequently, it turned out that this work, which immediately became extremely popular, was written not by Punyani at all, but by Kreisler, but the name of the Italian violinist, by that time thoroughly forgotten, had already attracted attention. Who is he? When he lived, what was his legacy really, what was he like as a performer and composer? Unfortunately, it is impossible to give an exhaustive answer to all these questions, because history has preserved too few documentary materials about Punyani.

Contemporaries and later researchers, who evaluated the Italian violin culture of the second half of the XNUMXth century, counted Punyani among its most prominent representatives.

In Fayol’s Communication, a small book about the greatest violinists of the XNUMXth century, Pugnani’s name is placed immediately after Corelli, Tartini and Gavignier, which confirms what a high place he occupied in the musical world of his era. According to E. Buchan, “the noble and majestic style of Gaetano Pugnani” was the last link in the style, the founder of which was Arcangelo Corelli.

Pugnani was not only a wonderful performer, but also a teacher who brought up a galaxy of excellent violinists, including Viotti. He was a prolific composer. His operas were staged in the largest theaters in the country, and his instrumental compositions were published in London, Amsterdam, and Paris.

Punyani lived at a time when the musical culture of Italy was beginning to fade. The spiritual atmosphere of the country was no longer the one that once surrounded Corelli, Locatelli, Geminiani, Tartini – the immediate predecessors of Punyani. The pulse of a turbulent social life now beat not here, but in neighboring France, where Punyani’s best student, Viotti, would not in vain rush. Italy is still famous for the names of many great musicians, but, alas, a very significant number of them are forced to seek employment for their forces outside their homeland. Boccherini finds shelter in Spain, Viotti and Cherubini in France, Sarti and Cavos in Russia… Italy is turning into a supplier of musicians for other countries.

There were serious reasons for this. By the middle of the XNUMXth century, the country was fragmented into a number of principalities; heavy Austrian oppression was experienced by the northern regions. The rest of the “independent” Italian states, in essence, also depended on Austria. The economy was in deep decline. The once lively trading city-republics turned into a kind of “museums” with a frozen, motionless life. Feudal and foreign oppression led to peasant uprisings and mass emigration of peasants to France, Switzerland, and Austria. True, foreigners who came to Italy still admired its high culture. And indeed, in almost every principality and even the town lived wonderful musicians. But few of the foreigners really understood that this culture was already leaving, conserving past conquests, but not paving the way for the future. Musical institutions consecrated by age-old traditions were preserved – the famous Academy of the Philharmonic in Bologna, orphanages – “conservatories” at the temples of Venice and Naples, famous for their choirs and orchestras; among the broadest masses of the people, a love for music was preserved, and often even in remote villages one could hear the playing of excellent musicians. At the same time, in the atmosphere of court life, music became more and more subtly aesthetic, and in churches – secularly entertaining. “The church music of the eighteenth century, if you will, is secular music,” wrote Vernon Lee, “it makes saints and angels sing like opera heroines and heroes.”

The musical life of Italy flowed measuredly, almost unchanged over the years. Tartini lived in Padua for about fifty years, playing weekly in the collection of St. Anthony; For over twenty years, Punyani was in the service of the King of Sardinia in Turin, performing as a violinist in the court chapel. According to Fayol, Pugnani was born in Turin in 1728, but Fayol is clearly mistaken. Most other books and encyclopedias give a different date – November 27, 1731. Punyani studied violin playing with the famous student of Corelli, Giovanni Battista Somis (1676-1763), who was considered one of the best violin teachers in Italy. Somis passed on to his student much of what was brought up in him by his great teacher. All of Italy admired the beauty of the sound of Somis’s violin, marveled at his “endless” bow, singing like a human voice. Commitment to the vocalized violin style, deep violin “bel canto” inherited from him and Punyani. In 1752, he took the place of the first violinist in the Turin court orchestra, and in 1753 he went to the musical Mecca of the XNUMXth century – Paris, where musicians from all over the world rushed at that time. In Paris, the first concert hall in Europe operated – the forerunner of the future philharmonic halls of the XNUMXth century – the famous Concert Spirituel (Spiritual Concert). The performance at the Concert Spirituel was considered very honorable, and all the greatest performers of the XNUMXth century visited its stage. It was difficult for the young virtuoso, because in Paris he encountered such brilliant violinists as P. Gavinier, I. Stamitz and one of the best students of Tartini, the Frenchman A. Pagen.

Although his game was received very favorably, however, Punyani did not stay in the French capital. For some time he traveled around Europe, then settled in London, getting a job as an accompanist of the orchestra of the Italian Opera. In London, his skill as a performer and composer finally matures. Here he composes his first opera Nanette and Lubino, performs as a violinist and tests himself as a conductor; from here, consumed by homesickness, in 1770, taking advantage of the invitation of the king of Sardinia, he returned to Turin. From now until his death, which followed on July 15, 1798, Punyani’s life is connected mainly with his native city.

The situation in which Pugnani found himself is beautifully described by Burney, who visited Turin in 1770, that is, shortly after the violinist moved there. Burney writes: “A gloomy monotony of daily repeated solemn parades and prayers reigns at court, which makes Turin the most boring place for foreigners …” “The king, the royal family and the whole city, apparently, constantly listen to mass; on ordinary days, their piety is silently embodied in Messa bassa (i.e., “Silent Mass” – morning church service. – L.R.) during a symphony. On holidays Signor Punyani plays solo… The organ is located in the gallery opposite the king, and the chief of the first violinists is also there.” “Their salary (i.e., Punyani and other musicians. – L. R.) for the maintenance of the royal chapel is slightly more than eight guineas a year; but the duties are very light, since they only play solo, and even then only when they please.

In music, according to Burney, the king and his retinue understood a little, which was also reflected in the activities of the performers: “This morning, Signor Pugnani played a concert in the royal chapel, which was jam-packed for the occasion … I personally do not need to say anything about the game of Signor Pugnani ; his talent is so well known in England that there is no need for it. I only have to remark that he seems to make little effort; but this is not surprising, for neither His Majesty of Sardinia, nor anyone from the large royal family at the present time seems to be interested in music.

Little employed in the royal service, Punyani launched an intensive teaching activity. “Pugnani,” writes Fayol, “founded a whole school of violin playing in Turin, like Corelli in Rome and Tartini in Padua, from which came the first violinists of the late eighteenth century—Viotti, Bruni, Olivier, etc.” “It is noteworthy,” he further notes, “that Pugnani’s students were very capable orchestra conductors,” which, according to Fayol, they owed to the conducting talent of their teacher.

Pugnani was considered a first-class conductor, and when his operas were performed at the Turin Theater, he always conducted them. He writes with feeling about Punyani Rangoni’s conducting: “He ruled over the orchestra like a general over soldiers. His bow was the baton of the commander, which everyone obeyed with the greatest precision. With one blow of the bow, given in time, he either increased the sonority of the orchestra, then slowed it down, then revived it at will. He pointed out to the actors the slightest nuances and brought everyone to that perfect unity with which the performance is animated. Perspicaciously noticing in the object the main thing that every skillful accompanist must imagine, in order to emphasize and make noticeable the most essential in parts, he grasped the harmony, character, movement and style of the composition so instantly and so vividly that he could at the same moment convey this feeling to souls. singers and every member of the orchestra. For the XNUMXth century, such a conductor’s skill and artistic interpretive subtlety were truly amazing.

As for the creative heritage of Punyani, information about him is contradictory. Fayol writes that his operas were performed in many theaters in Italy with great success, and in Riemann’s Dictionary of Music we read that their success was average. It seems that in this case it is necessary to trust Fayol more – almost a contemporary of the violinist.

In the instrumental compositions of Punyani, Fayol notes the beauty and liveliness of the melodies, pointing out that his trio was so striking in the grandeur of style that Viotti borrowed one of the motives for his concerto from the first, in E-flat major.

In total, Punyani wrote 7 operas and a dramatic cantata; 9 violin concertos; published 14 sonatas for one violin, 6 string quartets, 6 quintets for 2 violins, 2 flutes and basses, 2 notebooks for violin duets, 3 notebooks for trios for 2 violins and bass and 12 “symphonies” (for 8 voices – for a string quartet, 2 oboes and 2 horns).

In 1780-1781, Punyani, together with his student Viotti, made a concert tour of Germany, ending with a visit to Russia. In St. Petersburg, Punyani and Viotti were favored by the imperial court. Viotti gave a concert in the palace, and Catherine II, fascinated by his playing, “tried in every possible way to keep the virtuoso in St. Petersburg. But Viotti did not stay there long and went to England. Viotti did not give public concerts in the Russian capital, demonstrating his art only in the salons of patrons. Petersburg heard the performance of Punyani in the “performances” of French comedians on March 11 and 14, 1781. The fact that “the glorious violinist Mr. Pulliani” would play in them was announced in the St. Petersburg Vedomosti. In No. 21 for 1781 of the same newspaper, Pugnani and Viotti, musicians with a servant Defler, are on the list of those leaving, “they live near the Blue Bridge in the house of His Excellency Count Ivan Grigorievich Chernyshev.” Travel to Germany and Russia was the last in the life of Punyani. All other years he spent without a break in Turin.

Fayol reports in an essay on Punyani some curious facts from his biography. At the beginning of his artistic career, as a violinist already gaining fame, Pugnani decided to meet Tartini. For this purpose, he went to Padua. The illustrious maestro received him very graciously. Encouraged by the reception, Punyani turned to Tartini with a request to express his opinion about his playing in all frankness and began the sonata. However, after a few bars, Tartini decisively stopped him.

– You play too high!

Punyani started again.

“And now you’re playing too low!”

The embarrassed musician put down the violin and humbly asked Tartini to take him as a student.

Punyani was ugly, but this did not affect his character at all. He had a cheerful disposition, loved jokes, and there were many jokes about him. Once he was asked what kind of bride he would like to have if he decided to marry – beautiful, but windy, or ugly, but virtuous. “Beauty causes pain in the head, and ugly damages visual acuity. This, approximately, – if I had a daughter and wanted to marry her, it would be better to choose a person for her without money at all, than money without a person!

Once Punyani was in a society where Voltaire read poetry. The musician listened with lively interest. The mistress of the house, Madame Denis, turned to Punyani with a request to perform something for the assembled guests. The maestro readily agreed. However, starting to play, he heard that Voltaire continued to talk loudly. Stopping the performance and putting the violin in the case, Punyani said: “Monsieur Voltaire writes very good poetry, but as far as music is concerned, he does not understand the devil in it.”

Punyani was touchy. Once, the owner of a faience factory in Turin, who was angry with Punyani for something, decided to take revenge on him and ordered his portrait to be engraved on the back of one of the vases. The offended artist called the manufacturer to the police. Arriving there, the manufacturer suddenly pulled out of his pocket a handkerchief with the image of King Frederick of Prussia and calmly blew his nose. Then he said: “I don’t think Monsieur Punyani has more right to be angry than the King of Prussia himself.”

During the game, Punyani sometimes came into a state of complete ecstasy and completely ceased to notice his surroundings. Once, while performing a concerto in a large company, he became so carried away that, forgetting everything, he advanced to the middle of the hall and came to his senses only when the cadenza was over. Another time, having lost his cadence, he turned quietly to the artist who was next to him: “My friend, read a prayer so that I can come to my senses!”).

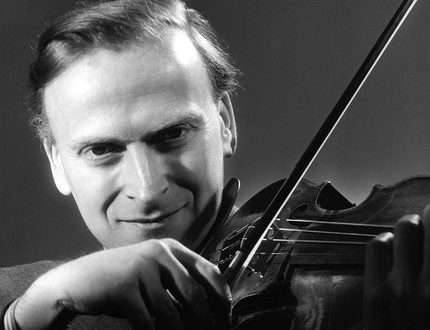

Punyani had an imposing and dignified posture. The grandiose style of his game fully corresponded to it. Not grace and gallantry, so common in that era among many Italian violinists, up to P. Nardini, but Fayol emphasizes strength, power, grandiosity in Pugnani. But it is these qualities that Viotti, Pugnani’s student, whose playing was regarded as the highest expression of the classical style in the violin performance of the late XNUMXth century, will especially impress the listeners with. Consequently, much of Viotti’s style was prepared by his teacher. For contemporaries, Viotti was the ideal of violin art, and therefore the posthumous epitaph expressed about Pugnani by the famous French violinist J. B. Cartier sounds like the highest praise: “He was Viotti’s teacher.”

L. Raaben