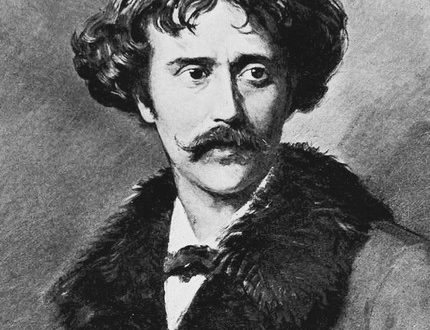

Grigory Pavlovich Pyatigorsky |

Gregor Piatigorsky

Grigory Pyatigorsky – a native of Yekaterinoslav (now Dnepropetrovsk). As he subsequently testified in his memoirs, his family had a very modest income, but did not starve. The most vivid childhood impressions for him were frequent walks with his father across the steppe near the Dnieper, visiting his grandfather’s bookshop and randomly reading the books stored there, as well as sitting in the basement with his parents, brother and sisters during the Yekaterinoslav pogrom. Gregory’s father was a violinist and, naturally, began to teach his son to play the violin. The father did not forget to give his son piano lessons. The Pyatigorsky family often attended musical performances and concerts at the local theater, and it was there that little Grisha saw and heard the cellist for the first time. His performance made such a deep impression on the child that he literally fell ill with this instrument.

He got two pieces of wood; I installed the larger one between my legs as a cello, while the smaller one was supposed to represent the bow. Even his violin he tried to install vertically so that it was something like a cello. Seeing all this, the father bought a small cello for a seven-year-old boy and invited a certain Yampolsky as a teacher. After the departure of Yampolsky, the director of the local music school became Grisha’s teacher. The boy made significant progress, and in the summer, when performers from different cities of Russia came to the city during symphony concerts, his father turned to the first cellist of the combined orchestra, a student of the famous professor of the Moscow Conservatory Y. Klengel, Mr. Kinkulkin with a request – to listen to his son. Kinkulkin listened to Grisha’s performance of a number of works, tapping his fingers on the table and maintaining a stony expression on his face. Then, when Grisha put the cello aside, he said: “Listen carefully, my boy. Tell your father that I strongly advise you to choose a profession that suits you better. Put the cello aside. You don’t have any ability to play it.” At first, Grisha was delighted: you can get rid of daily exercises and spend more time playing football with friends. But a week later, he began to look longingly in the direction of the cello that was lonely standing in the corner. The father noticed this and ordered the boy to resume his studies.

A few words about Grigory’s father, Pavel Pyatigorsky. In his youth, he overcame many obstacles to enter the Moscow Conservatory, where he became a student of the famous founder of the Russian violin school, Leopold Auer. Paul resisted the desire of his father, grandfather Gregory, to make him a bookseller (Paul’s father even disinherited his rebellious son). So Grigory inherited his craving for stringed instruments and persistence in his desire to become a musician from his father.

Grigory and his father went to Moscow, where the teenager entered the Conservatory and became a student of Gubarev, then von Glenn (the latter was a student of the famous cellists Karl Davydov and Brandukov). The financial situation of the family did not allow supporting Gregory (although, seeing his success, the directorate of the Conservatory released him from tuition fees). Therefore, the twelve-year-old boy had to earn extra money in Moscow cafes, playing in small ensembles. By the way, at the same time, he even managed to send money to his parents in Yekaterinoslav. In the summer, the orchestra with the participation of Grisha traveled outside of Moscow and toured the provinces. But in the fall, classes had to be resumed; besides, Grisha also attended a comprehensive school at the Conservatory.

Somehow, the famous pianist and composer Professor Keneman invited Grigory to take part in the concert of F.I. Chaliapin (Grigory was supposed to perform solo numbers between Chaliapin’s performances). Inexperienced Grisha, wanting to captivate the audience, played so brightly and expressively that the audience demanded an encore of the cello solo, angering the famous singer, whose appearance on stage was delayed.

When the October Revolution broke out, Gregory was only 14 years old. He took part in the competition for the position of soloist of the Bolshoi Theater Orchestra. After his performance of the Concerto for Cello and the Dvorak Orchestra, the jury, headed by the chief conductor of the theater V. Suk, invited Grigory to take the post of cello accompanist of the Bolshoi Theater. And Gregory immediately mastered the rather complex repertoire of the theater, played solo parts in ballets and operas.

At the same time, Grigory received a children’s food card! The soloists of the orchestra, and among them Grigory, organized ensembles that went out with concerts. Grigory and his colleagues performed in front of the luminaries of the Art Theater: Stanislavsky, Nemirovich-Danchenko, Kachalov and Moskvin; they participated in mixed concerts where Mayakovsky and Yesenin performed. Together with Isai Dobrovein and Fishberg-Mishakov, he performed as a trio; he happened to play in duets with Igumnov, Goldenweiser. He participated in the first Russian performance of the Ravel Trio. Soon, the teenager, who played the leading part of the cello, was no longer perceived as a kind of child prodigy: he was a full member of the creative team. When conductor Gregor Fitelberg arrived for the first performance of Richard Strauss’ Don Quixote in Russia, he said that the cello solo in this work was too difficult, so he specially invited Mr. Giskin.

Grigory modestly gave way to the invited soloist and sat down at the second cello console. But then the musicians suddenly protested. “Our cellist can play this part just as well as anyone else!” they said. Grigory was seated in his original place and performed the solo in such a way that Fitelberg hugged him, and the orchestra played carcasses!

After some time, Grigory became a member of the string quartet organized by Lev Zeitlin, whose performances were a notable success. People’s Commissar of Education Lunacharsky suggested that the quartet be named after Lenin. “Why not Beethoven?” Gregory asked in bewilderment. The performances of the quartet were so successful that he was invited to the Kremlin: it was necessary to perform Grieg’s Quartet for Lenin. After the end of the concert, Lenin thanked the participants and asked Grigory to linger.

Lenin asked if the cello was good, and received the answer – “so-so.” He noted that good instruments are in the hands of wealthy amateurs and should go into the hands of those musicians whose wealth lies only in their talent … “Is it true,” Lenin asked, “that you protested at the meeting about the name of the quartet? .. I, too, I believe that the name of Beethoven would suit the quartet better than the name of Lenin. Beethoven is something eternal…”

The ensemble, however, was named the “First State String Quartet”.

Still realizing the need to work with an experienced mentor, Grigory began to take lessons from the famous maestro Brandukov. However, he soon realized that private lessons were not enough – he was attracted to study at the conservatory. Seriously studying music at that time was possible only outside of Soviet Russia: many conservatory professors and teachers left the country. However, the People’s Commissar Lunacharsky refused the request to be allowed to go abroad: the People’s Commissar of Education believed that Grigory, as a soloist of the orchestra and as a member of the quartet, was indispensable. And then in the summer of 1921, Grigory joined the group of soloists of the Bolshoi Theater, who went on a concert tour of Ukraine. They performed in Kyiv, and then gave a number of concerts in small towns. In Volochisk, near the Polish border, they entered into negotiations with smugglers, who showed them the way to cross the border. At night, the musicians approached a small bridge across the Zbruch River, and the guides commanded them: “Run.” When warning shots were fired from both sides of the bridge, Grigory, holding the cello over his head, jumped from the bridge into the river. He was followed by the violinist Mishakov and others. The river was shallow enough that the fugitives soon reached Polish territory. “Well, we have crossed the border,” said Mishakov, trembling. “Not only,” Gregory objected, “we have burned our bridges forever.”

Many years later, when Piatigorsky arrived in the United States to give concerts, he told reporters about his life in Russia and how he left Russia. Having mixed up information about his childhood on the Dnieper and about jumping into the river on the Polish border, the reporter famously described Grigory’s cello swim across the Dnieper. I made the title of his article the title of this publication.

Further events unfolded no less dramatically. The Polish border guards assumed that the musicians who crossed the border were agents of the GPU and demanded that they play something. Wet emigrants performed Kreisler’s “Beautiful Rosemary” (instead of presenting documents that the performers did not have). Then they were sent to the commandant’s office, but on the way they managed to elude the guards and board a train going to Lvov. From there, Gregory went to Warsaw, where he met the conductor Fitelberg, who met Pyatigorsky during the first performance of Strauss’ Don Quixote in Moscow. After that, Grigory became an assistant cello accompanist in the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra. Soon he moved to Germany and finally achieved his goal: he began to study with the famous professors Becker and Klengel at the Leipzig and then Berlin conservatories. But alas, he felt that neither one nor the other could teach him anything worthwhile. In order to feed himself and pay for his studies, he joined an instrumental trio that played in a Russian cafe in Berlin. This cafe was often visited by artists, in particular, the famous cellist Emmanuil Feuerman and the no less famous conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler. Having heard the cellist Pyatigorsky play, Furtwängler, on the advice of Feuerman, offered Grigory the post of cello accompanist in the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. Gregory agreed, and that was the end of his studies.

Often, Gregory had to perform as a soloist, accompanied by the Philharmonic Orchestra. Once he performed the solo part in Don Quixote in the presence of the author, Richard Strauss, and the latter declared publicly: “Finally, I heard my Don Quixote the way I intended it!”

Having worked at the Berlin Philharmonic until 1929, Gregory decided to leave his orchestral career in favor of a solo career. This year he traveled to the USA for the first time and performed with the Philadelphia Orchestra, directed by Leopold Stokowski. He also performed solo with the New York Philharmonic under Willem Mengelberg. Pyatigorsky’s performances in Europe and the USA were a huge success. The impresarios who invited him admired the speed with which Grigory prepared new things for him. Along with the works of the classics, Pyatigorsky willingly took up the performance of opuses by contemporary composers. There were cases when the authors gave him rather raw, hastily finished works (composers, as a rule, receive an order by a certain date, a composition is sometimes added right before the performance, during rehearsals), and he had to perform the solo cello part according to the orchestral score. Thus, in the Castelnuovo-Tedesco cello concerto (1935), the parts were so carelessly scheduled that a significant part of the rehearsal consisted in their harmonization by the performers and the introduction of corrections into the notes. The conductor – and this was the great Toscanini – was extremely dissatisfied.

Gregory showed a keen interest in the works of forgotten or insufficiently performed authors. Thus, he paved the way for the performance of Bloch’s “Schelomo” by presenting it to the public for the first time (together with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra). He was the first performer of many works by Webern, Hindemith (1941), Walton (1957). In gratitude for the support of modern music, many of them dedicated their works to him. When Piatigorsky became friends with Prokofiev, who was living abroad at the time, the latter wrote the Cello Concerto (1933) for him, which was performed by Grigory with the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Sergei Koussevitzky (also a native of Russia). After the performance, Pyatigorsky drew the composer’s attention to some roughness in the cello part, apparently related to the fact that Prokofiev did not know the possibilities of this instrument well enough. The composer promised to make corrections and finalize the solo part of the cello, but already in Russia, since at that time he was going to return to his homeland. In the Union, Prokofiev completely revised the Concerto, turning it into the Concert Symphony, opus 125. The author dedicated this work to Mstislav Rostropovich.

Pyatigorsky asked Igor Stravinsky to arrange for him a suite on the theme of “Petrushka”, and this work by the master, entitled “Italian Suite for Cello and Piano”, was dedicated to Pyatigorsky.

Through the efforts of Grigory Pyatigorsky, a chamber ensemble was created with the participation of outstanding masters: pianist Arthur Rubinstein, violinist Yasha Heifetz and violist William Primroz. This quartet was very popular and recorded about 30 long-playing records. Piatigorsky also liked to play music as part of a “home trio” with his old friends in Germany: pianist Vladimir Horowitz and violinist Nathan Milstein.

In 1942, Pyatigorsky became a US citizen (before that, he was considered a refugee from Russia and lived on the so-called Nansen passport, which sometimes created inconvenience, especially when moving from country to country).

In 1947, Piatigorsky played himself in the film Carnegie Hall. On the stage of the famous concert hall, he performed the “Swan” by Saint-Saens, accompanied by harps. He recalled that the pre-recording of this piece included his own playing accompanied by only one harpist. On the set of the film, the authors of the film put almost a dozen harpists on the stage behind the cellist, who allegedly played in unison …

A few words about the film itself. I strongly encourage readers to seek out this old tape at video rental stores (Written by Karl Kamb, Directed by Edgar G. Ulmer) as it is a unique documentary of the biggest performing musicians in the United States performing in the XNUMXs and XNUMXs. The film has a plot (if you wish, you can ignore it): this is a chronicle of the days of a certain Nora, whose whole life turned out to be connected with Carnegie Hall. As a girl, she is present at the opening of the hall and sees Tchaikovsky conducting the orchestra during the performance of his First Piano Concerto. Nora has been working at Carnegie Hall all her life (first as a cleaner, later as a manager) and is in the hall during performances of famous performers. Arthur Rubinstein, Yasha Heifets, Grigory Pyatigorsky, singers Jean Pierce, Lily Pons, Ezio Pinza and Rize Stevens appear on the screen; orchestras are played under the direction of Walter Damrosch, Artur Rodzinsky, Bruno Walter and Leopold Stokowski. In a word, you see and hear outstanding musicians performing wonderful music…

Pyatigorsky, in addition to performing activities, also composed works for the cello (Dance, Scherzo, Variations on a Theme of Paganini, Suite for 2 Cellos and Piano, etc.) Critics noted that he combines innate virtuosity with a refined sense of style and phrasing. Indeed, technical perfection was never an end in itself for him. The vibrating sound of Pyatigorsky’s cello had an unlimited number of shades, its wide expressiveness and aristocratic grandeur created a special connection between the performer and the audience. These qualities were best manifested in the performance of romantic music. In those years, only one cellist could compare with Piatigorsky: it was the great Pablo Casals. But during the war he was cut off from the audience, living as a hermit in the south of France, and in the post-war period he mostly remained in the same place, in Prades, where he organized music festivals.

Grigory Pyatigorsky was also a wonderful teacher, combining performing activities with active teaching. From 1941 to 1949 he held the cello department at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, and headed the chamber music department at Tanglewood. From 1957 to 1962 he taught at Boston University, and from 1962 until the end of his life he worked at the University of Southern California. In 1962, Pyatigorsky again ended up in Moscow (he was invited to the jury of the Tchaikovsky Competition. In 1966, he went to Moscow again in the same capacity). In 1962, the New York Cello Society established the Piatigorsky Prize in honor of Gregory, which is awarded annually to the most talented young cellist. Pyatigorsky was awarded the title of honorary doctor of science from several universities; in addition, he was awarded membership in the Legion of Honor. He was also repeatedly invited to the White House to participate in concerts.

Grigory Pyatigorsky died on August 6, 1976, and is buried in Los Angeles. There are many recordings of world classics performed by Pyatigorsky or ensembles with his participation in almost all libraries in the United States.

Such is the fate of the boy who jumped in time from the bridge into the Zbruch River, along which the Soviet-Polish border passed.

Yuri Serper