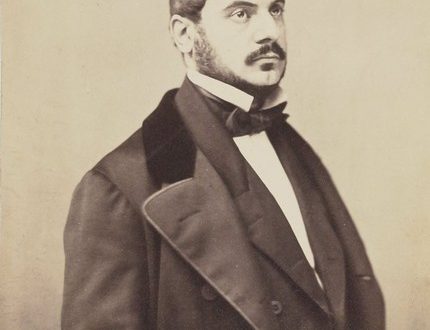

Ferdinand Laub |

Ferdinand Laub

The second half of the XNUMXth century was a time of rapid development of the liberation-democratic movement. The profound contradictions and contrasts of bourgeois society evoke passionate protests among the progressively minded intelligentsia. But the protest no longer has the character of a romantic rebellion of an individual against social inequality. Democratic ideas arise as a result of analysis and a realistically sober assessment of social life, the desire for knowledge and explanation of the world. In the sphere of art, the principles of realism are imperiously affirmed. In literature, this era was characterized by a powerful flowering of critical realism, which was also reflected in painting – the Russian Wanderers are an example of this; in music this led to psychologism, passionate people, and in the social activities of musicians – to enlightenment. The requirements for art are changing. Rushing into concert halls, wanting to learn from everything, the petty-bourgeois intelligentsia, known in Russia as “raznochintsy”, is eagerly drawn to deep, serious music. The slogan of the day is the fight against virtuosity, external showiness, salonism. All this gives rise to fundamental changes in musical life – in the repertoire of performers, in the methods of performing art.

The repertoire saturated with virtuoso works is being replaced by a repertoire enriched with artistically valuable creativity. It is not the spectacular pieces of the violinists themselves that are widely performed, but the concertos of Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and later – Brahms, Tchaikovsky. There comes a “revival” of the works of old masters of the XVII-XVIII centuries – J.-S. Bach, Corelli, Vivaldi, Tartini, Leclerc; in the chamber repertoire, particular attention is paid to Beethoven’s last quartets, which were previously rejected. In performance, the art of “artistic transformation”, “objective” transmission of the content and style of a work comes to the fore. The listener who comes to the concert is primarily interested in music, while the personality of the performer, skill is measured by his ability to convey the ideas contained in the works of composers. The essence of these changes was aphoristically accurately noted by L. Auer: “The epigraph – “music exists for the virtuoso” is no longer recognized, and the expression “virtuoso exists for music” has become the credo of a true artist of our days.”

The brightest representatives of the new artistic trend in violin performance were F. Laub, J. Joachim and L. Auer. It was they who developed the foundations of the realistic method in performance, were the creators of its principles, although subjectively Laub still connected a lot with romanticism.

Ferdinand Laub was born on January 19, 1832 in Prague. The violinist’s father, Erasmus, was a musician and his first teacher. The first performance of the 6-year-old violinist took place in a private concert. He was so small that he had to be put on the table. At the age of 8, Laub appeared before the Prague public already in a public concert, and some time later went with his father on a concert tour of the cities of his native country. The Norwegian violinist Ole Bull, to whom the boy was once brought, is delighted with his talent.

In 1843, Laub entered the Prague Conservatory in the class of Professor Mildner and graduated brilliantly at the age of 14. The performance of the young musician attracts attention, and Laub, having graduated from the conservatory, does not lack concerts.

His youth coincided with the time of the so-called “Czech Renaissance” – the rapid development of national liberation ideas. Throughout his life, Laub retained a fiery patriotism, an endless love for an enslaved, suffering homeland. After the Prague uprising of 1848, suppressed by the Austrian authorities, terror reigned in the country. Thousands of patriots are forced into exile. Among them is F. Laub, who settles for 2 years in Vienna. He plays here in the opera orchestra, taking the position of soloist and accompanist in it, improving in music theory and counterpoint with Shimon Sekhter, a Czech composer who settled in Vienna.

In 1859, Laub moved to Weimar to take the place of Josef Joachim, who had left for Hannover. Weimar – the residence of Liszt, played a big role in the development of the violinist. As a soloist and concertmaster of the orchestra, he constantly communicates with Liszt, who highly appreciates the wonderful performer. In Weimar, Laub became friends with Smetana, fully sharing his patriotic aspirations and hopes. From Weimar, Laub often travels with concerts to Prague and other cities of the Czech Republic. “At that time,” writes musicologist L. Ginzburg, “when Czech speech was persecuted even in Czech cities, Laub did not hesitate to speak his native language while in Germany. His wife later recalled how Smetana, meeting with Laub at Liszt in Weimar, was horrified by the boldness with which Laub spoke in Czech in the center of Germany.

A year after moving to Weimar, Laub married Anna Maresh. He met her in Novaya Guta, on one of his visits to his homeland. Anna Maresh was a singer and how Anna Laub rose to fame by frequently touring with her husband. She gave birth to five children – two sons and three daughters, and throughout her life was his most devoted friend. Violinist I. Grzhimali was married to one of his daughters, Isabella.

Laub’s skill was admired by the world’s greatest musicians, but in the early 50s his playing was mostly noted for virtuosity. In a letter to his brother in London in 1852, Joachim wrote: “It is amazing what a brilliant technique this man possesses; there is no difficulty for him.” Laub’s repertoire at that time was filled with virtuoso music. He willingly performs the concertos and fantasies of Bazzini, Ernst, Vietana. Later, the focus of his attention moves to the classics. After all, it was Laub who, in his interpretation of the works of Bach, concertos and ensembles of Mozart and Beethoven, was to a certain extent the predecessor and then rival of Joachim.

Laub’s quartet activities played an important role in deepening interest in the classics. In 1860, Joachim calls Laub “the best violinist among his colleagues” and enthusiastically evaluates him as a quartet player.

In 1856, Laub accepted an invitation from the Berlin court and settled in the Prussian capital. His activities here are extremely intense – he performs in a trio with Hans Bülow and Wohlers, gives quartet evenings, promotes the classics, including Beethoven’s latest quartets. Before Laub, public quartet evenings in Berlin in the 40s were held by an ensemble headed by Zimmermann; Laub’s historical merit was that his chamber concerts became permanent. The quartet operated from 1856 to 1862 and did much to educate the tastes of the public, clearing the way for Joachim. Work in Berlin was combined with concert trips, especially often to the Czech Republic, where he lived for a long time in the summer.

In 1859 Laub visited Russia for the first time. His performances in St. Petersburg with programs that included works by Bach, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, cause a sensation. Outstanding Russian critics V. Odoevsky, A. Serov are delighted with his performance. In one of the letters relating to this time, Serov called Laub “a true demigod.” “On Sunday at Vielgorsky’s I heard only two quartets (Beethoven’s in F-dur, from the Razumovskys, op. 59, and Haydn’s in G-dur), but what was that!! Even in the mechanism, Viettan outdid himself.

Serov devotes a series of articles to Laub, paying special attention to his interpretation of the music of Bach, Mendelssohn, and Beethoven. Bach’s Chaconne, again the astonishment of Laub’s bow and left hand, writes Serov, his thickest tone, the wide band of sound under his bow, which amplifies the violin four times against the usual one, his most delicate nuances in “pianissimo”, his incomparable phrasing, with deep understanding the deep style of Bach! .. Listening to this delightful music performed by Laub’s delightful performance, you begin to wonder: can there still be other music in the world, a completely different style (not polyphonic), whether the right of citizenship in a lawsuit can have a different style, — as complete as the infinitely organic, polyphonic style of the great Sebastian?

Laub impresses Serov in Beethoven’s Concerto as well. After the concert on March 23, 1859, he wrote: “This time this wonderfully transparent; he sang bright, angelically sincere music with his bow even incomparably better than in his concert in the hall of the Noble Assembly. The virtuosity is amazing! But she does not exist in Laub for herself, but for the benefit of highly musical creations. If only all virtuosos understood their meaning and purpose in this way!” “In quartets,” writes Serov, after listening to the chamber evening, “Laub seems to be even taller than in solo. It completely merges with the music being performed, which many virtuosos, including Vieuxne, cannot do.”

An attractive moment in Laub’s quartet evenings for leading Petersburg musicians was the inclusion of Beethoven’s last quartets in the number of performed works. The inclination towards the third period of Beethoven’s work was characteristic of the democratic intelligentsia of the 50s: “… and in particular we tried to get acquainted in performance with Beethoven’s last quartets,” wrote D. Stasov. After that, it is clear why Laub’s chamber concerts were received so enthusiastically.

In the early 60s, Laub spent a lot of time in the Czech Republic. These years for the Czech Republic were sometimes a rapid rise in national musical culture. The foundations of Czech musical classics are laid by B. Smetana, with whom Laub maintains the closest ties. In 1861, a Czech theater was opened in Prague, and the 50th anniversary of the conservatory was solemnly celebrated. Laub plays the Beethoven Concerto at the anniversary party. He is a constant participant in all patriotic undertakings, an active member of the national association of art representatives “Crafty conversation”.

In the summer of 1861, when Laub lived in Baden-Baden, Borodin and his wife often came to see him, who, being a pianist, loved to play duets with Laub. Laub highly appreciated Borodin’s musical talent.

From Berlin, Laub moved to Vienna and lived here until 1865, developing concert and chamber activities. “To the Violin King Ferdinand Laub,” read the inscription on the golden wreath that was presented to him by the Vienna Philharmonic Society when Laub left Vienna.

In 1865 Laub went to Russia for the second time. On March 6, he plays at the evening at N. Rubinstein’s, and the Russian writer V. Sollogub, who was present there, in an open letter to Matvey Vielgorsky, published in Moskovskie Vedomosti, devotes the following lines to him: “… Laub’s game delighted me so much that I forgot and snow, and a blizzard, and illnesses… Calmness, sonority, simplicity, severity of style, lack of pretentiousness, distinctness and, at the same time, intimate inspiration, combined with extraordinary strength, seemed to me Laub’s distinctive properties … He is not dry, like a classic, not impetuous, like romantic. He is original, independent, he has, as Bryullov used to say, a gag. He cannot be compared with anyone. A true artist is always typical. He told me a lot and asked about you. He loves you from the bottom of his heart, as everyone who knows you loves you. In his manner, it seemed to me that he was simple, cordial, ready to recognize someone else’s dignity and was not offended by them in order to elevate his own importance.

So with a few strokes, Sollogub sketched an attractive image of Laub, a man and an artist. From his letter it is clear that Laub was already familiar and close with many Russian musicians, including Count Vielgorsky, a remarkable cellist, a student of B. Romberg, and a prominent musical figure in Russia.

After Laub’s performance of Mozart’s G minor Quintet, V. Odoevsky responded with an enthusiastic article: “Whoever has not heard Laub in Mozart’s G Minor Quintet,” he wrote, “has not heard this quintet. Which of the musicians does not know by heart that wondrous poem called the Hemole Quintet? But how rare it is to hear such a performance of him that would fully satisfy our artistic sense.

Laub came to Russia for the third time in 1866. The concerts given by him in St. Petersburg and Moscow finally strengthened his extraordinary popularity. Laub was apparently impressed by the atmosphere of Russian musical life. March 1, 1866 he signs a contract to work in the Moscow branch of the Russian Musical Society; at the invitation of N. Rubinstein, he becomes the first professor of the Moscow Conservatory, which opened in the fall of 1866.

Like Venyavsky and Auer in St. Petersburg, Laub performed the same duties in Moscow: at the conservatory he taught the violin class, the quartet class, led orchestras; was concertmaster and soloist of the symphony orchestra and first violinist in the quartet of the Moscow branch of the Russian Musical Society.

Laub lived in Moscow for 8 years, that is, almost until his death; The results of his work are great and invaluable. He stood out as a first-class teacher who trained about 30 violinists, among whom were V. Villuan, who graduated from the conservatory in 1873 with a gold medal, I. Loiko, who became a concert player, Tchaikovsky’s friend I. Kotek. The well-known Polish violinist S. Bartsevich began his education with Laub.

Laub’s performing activity, especially the chamber one, was highly valued by his contemporaries. “In Moscow,” Tchaikovsky wrote, “there is such a quartet performer, whom all Western European capitals look with envy …” According to Tchaikovsky, only Joachim can compete with Laub in the performance of classical works, “surpassing Laub in the ability to instrument touchingly tender melodies, but certainly inferior to him in the power of tone, in passion and noble energy.

Much later, in 1878, after Laub’s death, in one of his letters to von Meck, Tchaikovsky wrote about Laub’s performance of Adagio from Mozart’s G-moll quintet: “When Laub played this Adagio, I always hid in the very corner of the hall, so that they don’t see what is done to me from this music.

In Moscow, Laub was surrounded by a warm, friendly atmosphere. N. Rubinstein, Kossman, Albrecht, Tchaikovsky – all major Moscow musical figures were in great friendship with him. In Tchaikovsky’s letters from 1866, there are lines that testify to close communication with Laub: “I am sending you a rather witty menu for one dinner at Prince Odoevsky, which I attended with Rubinstein, Laub, Kossmann and Albrecht, show it to Davydov.”

The Laubov Quartet in Rubinstein’s apartment was the first to perform Tchaikovsky’s Second Quartet; The great composer dedicated his Third Quartet to Laub.

Laub loved Russia. Several times he gave concerts in provincial cities – Vitebsk, Smolensk, Yaroslavl; his game was listened to in Kyiv, Odessa, Kharkov.

He lived with his family in Moscow on Tverskoy Boulevard. The flower of musical Moscow gathered in his house. Laub was easy to handle, although he always carried himself proudly and with dignity. He was distinguished by great diligence in everything related to his profession: “He played and practiced almost continuously, and when I asked him,” recalls Servas Heller, the educator of his children, “why is he still so tense when he has already reached, perhaps , the pinnacle of virtuosity, he laughed as if he took pity on me, and then said seriously: “As soon as I stop improving, it will immediately turn out that someone plays better than me, and I don’t want to.”

Great friendship and artistic interests closely connected Laub with N. Rubinstein, who became his constant partner in sonata evenings: “He and N. G. Rubinstein very much suited each other in terms of the nature of the game, and their duets were sometimes incomparably good. Hardly anyone has heard, for example, the best performance of Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata, in which both artists competed in the strength, tenderness and passion of the game. They were so sure of each other that sometimes they played things publicly unknown to them without rehearsals, directly a livre ouvert.

In the midst of Laub’s triumphs, illness suddenly overtook him. In the summer of 1874, doctors recommended that he go to Karlsbad (Karlovy Vary). As if anticipating the near end, Laub stopped along the way in the Czech villages dear to his heart – first in Křivoklát, where he planted a hazel bush in front of the house in which he once lived, then in Novaya Guta, where he played several quartets with relatives.

Treatment in Karlovy Vary did not go well and the completely ill artist was transferred to the Tyrolean Gris. Here, on March 18, 1875, he died.

Tchaikovsky, in his review of a concert by virtuoso violinist K. Sivori, wrote: “Listening to him, I thought about what was on the same stage exactly a year ago. for the last time another violinist played before the public, full of life and strength, in all the flowering of genius talent; that this violinist will no longer appear before any human audience, that no one will be thrilled by the hand that made sounds so strong, powerful and at the same time tender and caressing. G. Laub died only at the age of 43.”

L. Raaben