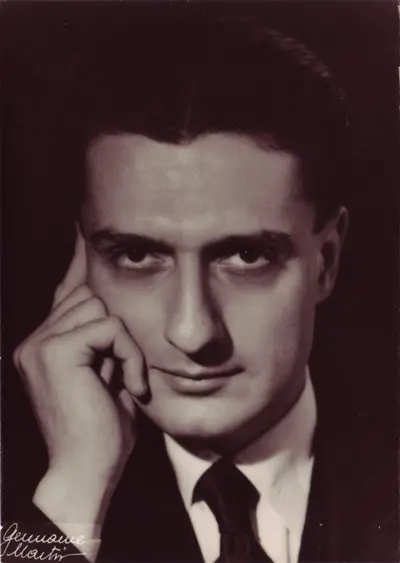

Dinu Lipatti (Dinu Lipatti) |

Dino Lipatti

His name has long become the property of history: about five decades have passed since the death of the artist. During this time, many stars have risen and set on the concert stages of the world, several generations of outstanding pianists have grown up, new trends in the performing arts have been established – those that are commonly called “modern performing style”. And meanwhile, the legacy of Dinu Lipatti, unlike the legacy of many other major artists of the first half of our century, has not been covered with a “flair of a museum”, has not lost its charm, its freshness: it turned out to be beyond fashion, and moreover, not only continues to excite listeners, but also influences new generations of pianists. His recordings are not a source of pride for collectors of old discs – they are reissued again and again, sold out instantly. All this is happening not because Lipatti could well still be among us, be in his prime, if not for a ruthless illness. The reasons are deeper – in the very essence of his ageless art, in the deep truthfulness of feeling, as if cleansed of everything external, transient, multiplying the power of the influence of the musician’s talent and at this time distance.

Few artists managed to leave such a vivid mark in the memory of people in such a short time, allotted to them by fate. Especially if we remember that Lipatti was by no means a child prodigy in the generally accepted sense of the word, and relatively late began extensive concert activity. He grew up and developed in a musical atmosphere: his grandmother and mother were excellent pianists, his father was a passionate violinist (he even took lessons from P. Sarasate and K. Flesch). In a word, it is not surprising that the future musician, not yet knowing the alphabet, freely improvised on the piano. Childish gaiety was bizarrely combined in his uncomplicated compositions with surprising seriousness; such a combination of immediacy of feeling and depth of thought remained later, becoming a characteristic feature of a mature artist.

The first teacher of the eight-year-old Lipatti was the composer M. Zhora. Having discovered exceptional pianistic abilities in a student, in 1928 he handed him over to the famous teacher Florika Muzychesk. In those same years, he had another mentor and patron – George Enescu, who became the “godfather” of the young musician, who closely followed his development and helped him. At the age of 15, Lipatti graduated with honors from the Bucharest Conservatory, and soon won the Enescu Prize for his first major work, the symphonic paintings “Chetrari”. At the same time, the musician decided to take part in the International Piano Competition in Vienna, one of the most “massive” in terms of the number of participants in the history of competitions: then about 250 artists came to the Austrian capital. Lipatti was second (after B. Kohn), but many members of the jury called him the real winner. A. Cortot even left the jury in protest; in any case, he immediately invited the Romanian youth to Paris.

Lipatti lived in the capital of France for five years. He improved with A. Cortot and I. Lefebur, attended the class of Nadia Boulanger, took conducting lessons from C. Munsch, composition from I. Stravinsky and P. Duke. Boulanger, who brought up dozens of major composers, said this about Lipatti: “A real musician in the full sense of the word can be considered one who devotes himself entirely to music, forgetting about himself. I can safely say that Lipatti is one of those artists. And that is the best explanation for my belief in him.” It was with Boulanger that Lipatti made his first recording in 1937: Brahms’ four-handed dances.

At the same time, the concert activity of the artist began. Already his first performances in Berlin and the cities of Italy attracted everyone’s attention. After his Parisian debut, critics compared him to Horowitz and unanimously predicted a bright future for him. Lipatti visited Sweden, Finland, Austria, Switzerland, and everywhere he was successful. With each concert, his talent opened up with new facets. This was facilitated by his self-criticism, his creative method: before bringing his interpretation to the stage, he achieved not only a perfect mastery of the text, but also a complete fusion with the music, which resulted in the deepest penetration into the author’s intention.

It is characteristic that only in recent years he began to turn to Beethoven’s heritage, and earlier he considered himself not ready for this. One day he remarked that it took him four years to prepare Beethoven’s Fifth Concerto or Tchaikovsky’s First. Of course, this does not speak of his limited abilities, but only of his extreme demands on himself. But each of his performances is the discovery of something new. Remaining scrupulously faithful to the author’s text, the pianist always set off the interpretation with the “colors” of his individuality.

One of these signs of his individuality was the amazing naturalness of phrasing: external simplicity, clarity of concepts. At the same time, for each composer, he found special piano colors that corresponded to his own worldview. His Bach sounded like a protest against the skinny “museum” reproduction of the great classic. “Who dares to think of the cembalo while listening to the First Partita performed by Lipatti, filled with such nervous force, such melodious legato and such aristocratic grace?” exclaimed one of the critics. Mozart attracted him, first of all, not with grace and lightness, but with excitement, even drama and fortitude. “No concessions to gallant style,” his game seems to say. This is emphasized by rhythmic rigor, mean pedaling, energetic touch. His understanding of Chopin lies in the same plane: no sentimentality, strict simplicity, and at the same time – a huge power of feeling …

The Second World War found the artist in Switzerland, on another tour. He returned to his homeland, continued to perform, compose music. But the suffocating atmosphere of fascist Romania suppressed him, and in 1943 he managed to leave for Stockholm, and from there to Switzerland, which became his last refuge. He headed the performing department and piano class at the Geneva Conservatory. But just at the moment when the war ended and brilliant prospects opened up before the artist, the first signs of an incurable disease appeared – leukemia. He writes bitterly to his teacher M. Zhora: “When I was healthy, the fight against want was tiring. Now that I’m sick, there are invitations from all countries. I signed engagements with Australia, South and North America. What an irony of fate! But I don’t give up. I will fight no matter what.”

The fight went on for years. Long tours had to be cancelled. In the second half of the 40s, he hardly left Switzerland; the exception was his trips to London, where he made his debut in 1946 together with G. Karajan, playing Schumann’s Concerto under his direction. Lipatti later traveled to England several more times to record. But in 1950, he could no longer endure even such a trip, and the firm of I-am-a sent their “team” to him in Geneva: in a few days, at the cost of the greatest effort, 14 Chopin waltzes, Mozart’s Sonata (No. 8) were recorded , Bach Partita (B flat major), Chopin’s 32nd Mazurka. In August, he performed with the orchestra for the last time: Mozart’s Concerto (No. 21) sounded, G. Karayan was at the podium. And on September 16, Dinu Lipatti said goodbye to the audience in Besançon. The concert program included Bach’s Partita in B flat major, Mozart’s Sonata, two impromptu by Schubert and all 14 waltzes by Chopin. He played only 13 – the last one was no longer strong enough. But instead, realizing that he would never again be on the stage, the artist performed the Bach Chorale, arranged for piano by Myra Hess… The recording of this concerto became one of the most exciting, dramatic documents in the musical history of our century…

After Lipatti’s death, his teacher and friend A. Cortot wrote: “Dear Dinu, your temporary stay among us not only put you forward by common consent to the first place among the pianists of your generation. In the memory of those who listened to you, you leave the confidence that if fate had not been so cruel to you, then your name would have become a legend, an example of selfless service to art. The time that has passed since then has shown that Lipatti’s art remains such an example to this day. His sound legacy is comparatively small – only about nine hours of recordings (if you count repetitions). In addition to the above-mentioned compositions, he managed to capture on records such concertos by Bach (No. 1), Chopin (No. 1), Grieg, Schumann, plays by Bach, Mozart, Scarlatti, Liszt, Ravel, his own compositions – Concertino in the classical style and Sonata for the left hands … That’s almost all. But everyone who gets acquainted with these records will certainly agree with the words of Florica Muzycescu: “The artistic speech with which he addressed people has always captured the audience, it also captures those who listen to his playing on the record.”

Grigoriev L., Platek Ya.