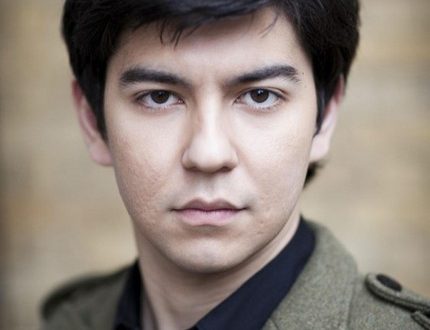

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli) |

Arturo Benedetti by Michelangelo

None of the notable musicians of the XNUMXth century had so many legends, so many incredible stories told. Michelangeli received the titles “Man of Mystery”, “Tangle of Secrets”, “The Most Incomprehensible Artist of Our Time”.

“Bendetti Michelangeli is an outstanding pianist of the XNUMXth century, one of the largest figures in the world of performing arts,” writes A. Merkulov. – The brightest creative individuality of the musician is determined by a unique fusion of heterogeneous, sometimes seemingly mutually exclusive features: on the one hand, the amazing penetration and emotionality of the utterance, on the other hand, the rare intellectual fullness of ideas. Moreover, each of these basic qualities, internally multi-component, is brought in the art of the Italian pianist to new degrees of manifestation. Thus, the boundaries of the emotional sphere in Benedetti’s play range from scorching openness, piercing trepidation and impulsiveness to exceptional refinement, refinement, sophistication, sophistication. Intellectuality is also manifested in the creation of deep philosophical performance concepts, and in the impeccable logical alignment of interpretations, and in a certain detachment, coldish contemplation of a number of his interpretations, and in minimizing the improvisational element in playing on stage.

- Piano music in the Ozon online store →

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli was born on January 5, 1920 in the city of Brescia, in northern Italy. He received his first music lessons at the age of four. At first he studied the violin, and then began to study the piano. But since in childhood Arturo had been ill with pneumonia, which turned into tuberculosis, the violin had to be left.

The poor health of the young musician did not allow him to carry a double load.

Michelangeli’s first mentor was Paulo Kemeri. At the age of fourteen, Arturo graduated from the Milan Conservatory in the class of the famous pianist Giovanni Anfossi.

It seemed that the future of Michelangeli was decided. But suddenly he leaves for the Franciscan monastery, where he works as an organist for about a year. Michelangeli did not become a monk. At the same time, the environment influenced the worldview of the musician.

In 1938, Michelangeli participated in the International Piano Competition in Brussels, where he took only seventh place. Competition jury member S. E. Feinberg, probably referring to the salon-romantic liberties of the best Italian contestants, wrote then that they play “with external brilliance, but very mannered”, and that their performance “is distinguished by the complete lack of ideas in the interpretation of the work” .

Fame came to Michelangeli after winning the competition in Geneva in 1939. “A new Liszt was born,” music critics wrote. A. Cortot and other jury members gave an enthusiastic assessment of the young Italian’s game. It seemed that now nothing would prevent Michelangeli from developing success, but World War II soon began. – He takes part in the resistance movement, mastering the profession of a pilot, fighting against the Nazis.

He is wounded in the hand, arrested, put in prison, where he spends about 8 months, seizing the opportunity, he escapes from prison – and how he runs! on a stolen enemy plane. It is difficult to say where is the truth and where is fiction about Michelangeli’s military youth. He himself was extremely reluctant to touch on this topic in his conversations with journalists. But even if there is at least half the truth here, it remains only to be amazed – there was nothing like this in the world either before Michelangeli or after him.

“At the end of the war, Michelangeli is finally returning to music. The pianist performs on the most prestigious stages in Europe and the USA. But he wouldn’t be Michelangeli if he did everything like others. “I never play for other people,” Michelangeli once said, “I play for myself And for me, in general, it doesn’t matter if there are listeners in the hall or not. When I am at the piano keyboard, everything around me disappears.

There is only music and nothing but music.”

The pianist went on stage only when he felt in shape and was in the mood. The musician also had to be completely satisfied with the acoustic and other conditions associated with the upcoming performance. It is not surprising that often all the factors did not coincide, and the concert was canceled.

No one has probably had such a large number of announced and canceled concerts as Michelangeli’s. Detractors even claimed that the pianist canceled more concerts than gave them! Michelangeli once turned down a performance at Carnegie Hall itself! He didn’t like the piano, or maybe its tuning.

In fairness, it must be said that such refusals cannot be attributed to a whim. An example can be given when Michelangeli got into a car accident and broke his rib, and after a few hours he went on stage.

After that, he spent a year in the hospital! The pianist’s repertoire consisted of a small number of works by different authors:

Scarlatti, Bach, Busoni, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Chopin, Schumann, Brahms, Rachmaninov, Debussy, Ravel and others.

Michelangeli could learn a new piece for years before including it in his concert programs. But even later, he returned to this work more than once, finding new colors and emotional nuances in it. “When referring to music that I have played maybe tens or hundreds of times, I always start from the beginning,” he said. It’s like it’s completely new music for me.

Every time I start with ideas that occupy me at the moment.

The musician’s style completely excluded the subjectivist approach to the work:

“My task is to express the intention of the author, the will of the author, to embody the spirit and letter of the music I perform,” he said. — I try to read the text of a piece of music correctly. Everything is there, everything is marked. Michelangeli strived for one thing – perfection.

That is why he toured the cities of Europe for a long time with his piano and tuner, despite the fact that the costs in this case often exceeded the fees for his performances. in terms of craftsmanship and the finest workmanship of sound “products,” Tsypin notes.

The well-known Moscow critic D. A. Rabinovich wrote in 1964, after the pianist’s tour in the USSR: “Michelangeli’s technique belongs to the most amazing among those that have ever existed. Taken to the limits of what is possible, it is beautiful. It causes delight, a feeling of admiration for the harmonious beauty of “absolute pianism”.

At the same time, an article by G. G. Neuhaus “Pianist Arturo Benedetti-Michelangeli” appeared, which said: “For the first time, the world-famous pianist Arturo Benedetti-Michelangeli came to the USSR. His first concerts in the Great Hall of the Conservatory immediately proved that the loud fame of this pianist was well-deserved, that the huge interest and impatient expectation shown by the audience that filled the concert hall to capacity were justified – and received complete satisfaction. Benedetti-Michelangeli turned out to be truly a pianist of the highest, highest class, next to whom only rare, few units can be placed. It is difficult in a brief review to list everything that he so captivates the listener about him, I want to talk a lot and in detail, but even so, at least briefly, I will be allowed to note the main thing. First of all, it is necessary to mention the unheard-of perfection of his performance, a perfection that does not allow any accidents, fluctuations of the minute, no deviations from the ideal of performance, once recognized by him, established and worked out by enormous ascetic labor. Perfection, harmony in everything – in the general concept of the work, in technique, in sound, in the smallest detail, as well as in general.

His music resembles a marble statue, dazzlingly perfect, designed to stand for centuries without change, as if not subject to the laws of time, its contradictions and vicissitudes. If I may say so, its fulfillment is a kind of “standardization” of an extremely high and difficult to implement ideal, an extremely rare thing, almost unattainable, if we apply to the concept of “ideal” the criterion that P. I. Tchaikovsky applied to him, who believed that in all there are almost no perfect works in world music, that perfection is achieved only in the rarest cases, in fits and starts, despite the multitude of beautiful, excellent, talented, brilliant compositions. Like any very great pianist, Benedetti-Michelangeli has an unimaginably rich sound palette: the basis of music – time-sound – is developed and used to the limit. Here is a pianist who knows how to reproduce the first birth of sound and all its changes and gradations up to fortissimo, always remaining within the boundaries of grace and beauty. The plasticity of his game is amazing, the plasticity of a deep bas-relief, which gives a captivating play of chiaroscuro. Not only the performance of Debussy, the greatest painter in music, but also of Scarlatti and Beethoven abounded in the subtleties and charms of the sound fabric, its dissection and clarity, which are extremely rare to hear in such perfection.

Benedetti-Michelangeli not only listens and hears himself perfectly, but you have the impression that he thinks music while playing, you are present at the act of musical thinking, and therefore, it seems to me, his music has such an irresistible effect on the listener. He just makes you think along with him. This is what makes you listen and feel the music at his concerts.

And one more property, extremely characteristic of the modern pianist, is extremely inherent in him: he never plays himself, he plays the author, and how he plays! We heard Scarlatti, Bach (Chaconne), Beethoven (both early – the Third Sonata, and late – the 32nd Sonata), and Chopin, and Debussy, and each author appeared before us in his own unique individual originality. Only a performer who has comprehended the laws of music and art to the depths with his mind and heart can play like that. Needless to say, this requires (except for the mind and heart) the most advanced technical means (the development of the motor-muscular apparatus, the ideal symbiosis of the pianist with the instrument). In Benedetti-Michelangeli, it is developed in such a way that, listening to him, one admires not only his great talent, but also the enormous amount of work required in order to bring his intentions and his abilities to such perfection.

Along with performing activities, Michelangeli was also successfully engaged in pedagogy. He started in the pre-war years, but took up teaching seriously in the second half of the 1940s. Michelangeli taught piano classes at the conservatories of Bologna and Venice and some other Italian cities. The musician also founded his own school in Bolzano.

In addition, during the summer he organized international courses for young pianists in Arezzo, near Florence. The financial possibilities of the student interested Michelangeli almost in the least. Moreover, he is even ready to help talented people. The main thing is to be interesting with the student. “In this vein, more or less safely, outwardly, in any case, Michelangeli’s life flowed until the end of the sixties,” Tsypin writes. car racing, he was, by the way, almost a professional race car driver, received prizes in competitions. Michelangeli lived modestly, unpretentiously, he almost always walked in his favorite black sweater, his dwelling was not much different in decoration from the monastery cell. He played the piano most often at night, when he could completely disconnect from everything extraneous, from the external environment.

“It is very important not to lose contact with your own self,” he once said. “Before going out to the public, the artist must find a way to himself.” They say that Michelangeli’s work rate for the instrument was quite high: 7-8 hours a day. However, when they spoke to him on this topic, he answered somewhat irritably that he worked all 24 hours, only part of this work was done behind the piano keyboard, and part outside it.

In 1967-1968, the record company, with which Michelangeli was associated with some financial obligations, unexpectedly went bankrupt. The bailiff seized the musician’s property. “Michelangeli runs the risk of being left without a roof over his head,” the Italian press wrote these days. “The pianos, on which he continues the dramatic pursuit of perfection, no longer belong to him. The arrest also extends to income from his future concerts.”

Michelangeli bitterly, without waiting for help, leaves Italy and settles in Switzerland in Lugano. There he lived until his death on June 12, 1995. Concerts he recently gave less and less. Playing in various European countries, he never played again in Italy.

The majestic and stern figure of Benedetti Michelangeli, undoubtedly the greatest Italian pianist of the middle of our century, rises like a lonely peak in the mountain range of giants of world pianism. His whole appearance on the stage radiates sad concentration and detachment from the world. No posture, no theatricality, no fawning over the audience and no smile, no thanks for the applause after the concert. He does not seem to notice the applause: his mission is accomplished. The music that had just connected him to the people ceased to sound, and the contact ceased. Sometimes it seems that the audience even interferes with him, irritates him.

No one, perhaps, does so little to pour out and “present” himself in the music performed, as Benedetti Michelangeli. And at the same time – paradoxically – few people leave such an indelible imprint of personality on every piece they perform, on every phrase and in every sound, as he does. His playing impresses with its impeccability, durability, thorough thoughtfulness and finishing; it would seem that the element of improvisation, surprise is completely alien to her – everything has been worked out over the years, everything is logically soldered, everything can only be this way and nothing else.

But why, then, does this game capture the listener, involve him in its course, as if in front of him on the stage the work is being born anew, moreover, for the first time?!

The shadow of a tragic, some kind of inevitable fate hovers over the genius of Michelangeli, overshadowing everything that his fingers touch. It is worth comparing his Chopin with the same Chopin performed by others – the greatest pianists; it is worth listening to what a deep drama Grieg’s concerto appears in him – the very one that shines with beauty and lyrical poetry in other of his colleagues, in order to feel, almost to see with your own eyes this shadow, strikingly, improbably transforming the music itself. And Tchaikovsky’s First, Rachmaninoff’s Fourth – how different is this from everything you’ve heard before?! Is it any wonder after this that the experienced expert in piano art D. A. Rabinovich, who probably heard all the pianists of the century, having heard Benedetti Michelangeli on the stage, admitted; “I have never met such a pianist, such a handwriting, such an individuality – both extraordinary, and deep, and irresistibly attractive – I have never met in my life” …

Rereading dozens of articles and reviews about the Italian artist, written in Moscow and Paris, London and Prague, New York and Vienna, amazingly often, you will inevitably come across one word – one magic word, as if destined to determine his place in the world of contemporary art of interpretation. , is perfection. Indeed, a very accurate word. Michelangeli is a true knight of perfection, striving for the ideal of harmony and beauty all his life and every minute at the piano, reaching heights and constantly dissatisfied with what he has achieved. Perfection is in virtuosity, in the clarity of intention, in the beauty of sound, in the harmony of the whole.

Comparing the pianist with the great Renaissance artist Raphael, D. Rabinovich writes: “It is the Raphael principle that is poured into his art and determines its most important features. This game, characterized primarily by perfection – unsurpassed, incomprehensible. It makes itself known everywhere. Michelangeli’s technique is one of the most amazing that has ever existed. Brought to the limits of the possible, it is not intended to “shake”, “crush”. She is beautiful. It evokes delight, a feeling of admiration for the harmonious beauty of absolute pianism… Michelangeli knows no barriers either in technique as such or in the sphere of color. Everything is subject to him, he can do whatever he wants, and this boundless apparatus, this perfection of form is completely subordinated to one task only – to achieve the perfection of the inner. The latter, despite the seemingly classical simplicity and economy of expression, impeccable logic and interpretative idea, is not easily perceived. When I listened to Michelangeli, at first it seemed to me that he played better from time to time. Then I realized that from time to time he pulled me more strongly into the orbit of his vast, deep, most complex creative world. Michelangeli’s performance is demanding. She is waiting to be listened to attentively, tensely. Yes, these words explain a lot, but even more unexpected are the words of the artist himself: “Perfection is a word that I never understood. Perfection means limitation, a vicious circle. Another thing is evolution. But the main thing is respect for the author. This does not mean that one should copy the notes and reproduce these copies by one’s performance, but one should try to interpret the author’s intentions, and not put his music in the service of one’s own personal goals.

So what is the meaning of this evolution that the musician speaks of? In constant approximation to the spirit and letter of what was created by the composer? In a continuous, “lifelong” process of overcoming oneself, the torment of which is so acutely felt by the listener? Probably in this as well. But also in that inevitable projection of one’s intellect, one’s mighty spirit onto the music being performed, which is sometimes capable of raising it to unprecedented heights, sometimes giving it a significance greater than that originally contained in it. This was once the case with Rachmaninoff, the only pianist whom Michelangeli bows to, and this happens with him himself, say, with B. Galuppi’s Sonata in C Major or many sonatas by D. Scarlatti.

You can often hear the opinion that Michelangeli, as it were, personifies a certain type of pianist of the XNUMXth century – the machine era in the development of mankind, a pianist who has no place for inspiration, for a creative impulse. This point of view has found supporters in our country as well. Impressed by the artist’s tour, G. M. Kogan wrote: “Michelangeli’s creative method is the flesh of the flesh of the ‘recording age’; the Italian pianist’s playing is perfectly adapted to her requirements. Hence the desire for “one hundred percent” accuracy, perfection, absolute infallibility, which characterizes this game, but also the decisive expulsion of the slightest elements of risk, breakthroughs into the “unknown”, what G. Neuhaus aptly called the “standardization” of performance. In contrast to the romantic pianists, under whose fingers the work itself seems immediately created, born anew, Michelangeli does not even create a performance on the stage: everything here is created in advance, measured and weighed, cast once and for all into an indestructibly magnificent form. From this finished form, the performer in the concert, with concentration and care, fold by fold, removes the veil, and an amazing statue appears in front of us in its marble perfection.

Undoubtedly, the element of spontaneity, spontaneity in the game of Michelangeli is absent. But does this mean that internal perfection is achieved once and for all, at home, in the course of quiet office work, and everything that is offered to the public is a kind of copy from a single model? But how can copies, no matter how good and perfect they are, again and again kindle inner awe in the listeners – and this has been happening for many decades?! How can an artist copying himself year after year stay on top?! And, finally, why is it then that the typical “recording pianist” so rarely and reluctantly, with such difficulty, records, why even today his records are negligible compared to the records of other, less “typical” pianists?

It is not easy to answer all these questions, to solve the riddle of Michelangeli to the end. Everyone agrees that we have before us the greatest piano artist. But something else is just as clear: the very essence of his art is such that, without leaving listeners indifferent, it is able to divide them into adherents and opponents, into those to whom the artist’s soul and talent are close, and those to whom he is alien. In any case, this art cannot be called elitist. Refined – yes, but elite – no! The artist does not aim to talk only with the elite, he “talks” as if to himself, and the listener – the listener is free to agree and admire or argue – but still admire him. It is impossible not to listen to the voice of Michelangeli – such is the imperious, mysterious power of his talent.

Perhaps the answer to many questions lies partly in his words: “A pianist should not express himself. The main thing, the most important thing, is to feel the spirit of the composer. I tried to develop and educate this quality in my students. The trouble with the current generation of young artists is that they are completely focused on expressing themselves. And this is a trap: once you fall into it, you find yourself in a dead end from which there is no way out. The main thing for a performing musician is to merge with the thoughts and feelings of the person who created the music. Learning music is just the beginning. The pianist’s true personality begins to reveal itself only when he comes into deep intellectual and emotional communication with the composer. We can talk about musical creativity only if the composer has completely mastered the pianist … I do not play for others – only for myself and for the sake of serving the composer. It makes no difference to me whether to play for the public or not. When I sit down at the keyboard, everything around me ceases to exist. I think about what I’m playing, about the sound I’m making, because it’s a product of the mind.”

Mysteriousness, mystery envelop not only the art of Michelangeli; many romantic legends are connected with his biography. “I am a Slav by origin, at least a particle of Slavic blood flows in my veins, and I consider Austria to be my homeland. You can call me a Slav by birth and an Austrian by culture,” the pianist, who is known all over the world as the greatest Italian master, who was born in Brescia and spent most of his life in Italy, once told a correspondent.

His path was not strewn with roses. Having started studying music at the age of 4, he dreamed of becoming a violinist until the age of 10, but after pneumonia he fell ill with tuberculosis and was forced to “retrain” on the piano, since many movements associated with playing the violin were contraindicated for him. However, it was the violin and the organ (“Speaking of my sound,” he notes, “we should not talk about the piano, but about the combination of organ and violin”), according to him, helped him find his method. Already at the age of 14, the young man graduated from the Milan Conservatory, where he studied with Professor Giovanni Anfossi (and along the way he studied medicine for a long time).

In 1938 he received the seventh prize at an international competition in Brussels. Now this is often written about as a “strange failure”, a “fatal mistake of the jury”, forgetting that the Italian pianist was only 17 years old, that he first tried his hand at such a difficult competition, where the rivals were exceptionally strong: many of them also became soon stars of the first magnitude. But two years later, Michelangeli easily became the winner of the Geneva competition and got the opportunity to start a brilliant career, if the war had not interfered. The artist does not recall those years too readily, but it is known that he was an active participant in the Resistance movement, escaped from a German prison, became a partisan, and mastered the profession of a military pilot.

When the shots died down, Michelangeli was 25 years old; The pianist lost 5 of them during the war years, 3 more – in a sanatorium where he was treated for tuberculosis. But now bright prospects opened before him. However, Michelangeli is far from the type of modern concert player; always doubtful, unsure of himself. It hardly “fits” into the concert “conveyor” of our days. He spends years learning new pieces, canceling concerts every now and then (his detractors claim he canceled more than he played). Paying special attention to sound quality, the artist preferred to travel with his piano and his own tuner for a long time, which caused irritation of administrators and ironic remarks in the press. As a result, he spoils relations with entrepreneurs, with record companies, with newspapermen. Ridiculous rumors are spread about him, and a reputation for being a difficult, eccentric and intractable person is assigned to him.

Meanwhile, this person sees no other goal in front of him, except for selfless service to art. Traveling with the piano and the tuner cost him a good deal of the fee; but he gives many concerts only to help young pianists get a full-fledged education. He leads piano classes at the conservatories of Bologna and Venice, holds annual seminars in Arezzo, organizes his own school in Bergamo and Bolzano, where he not only receives no fees for his studies, but also pays scholarships to students; organizes and for several years holds international festivals of piano art, among the participants of which were the largest performers from different countries, including the Soviet pianist Yakov Flier.

Michelangeli reluctantly, “through force” is recorded, although firms pursue him with the most profitable offers. In the second half of the 60s, a group of businessmen drew him into the organization of his own enterprise, BDM-Polyfon, which was supposed to release his records. But commerce is not for Michelangeli, and soon the company goes bankrupt, and with it the artist. That is why in recent years he has not played in Italy, which failed to appreciate his “difficult son”. He does not play in the USA either, where a commercial spirit reigns, deeply alien to him. The artist also stopped teaching. He lives in a modest apartment in the Swiss town of Lugano, breaking this voluntary exile with tours – increasingly rare, since few of the impresario dare to conclude contracts with him, and illnesses do not leave him. But each of his concerts (most often in Prague or Vienna) turns into an unforgettable event for listeners, and each new recording confirms that the artist’s creative powers do not decrease: just listen to two volumes of Debussy’s Preludes, captured in 1978-1979.

In his “search for lost time,” Michelangeli over the years had to somewhat change his views on the repertoire. The public, in his words, “deprived him of the possibility of searching”; if in his early years he willingly played modern music, now he focused his interests mainly on the music of the XNUMXth and early XNUMXth centuries. But his repertoire is more diverse than it seems to many: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schumann, Chopin, Rachmaninov, Brahms, Liszt, Ravel, Debussy are represented in his programs by concerts, sonatas, cycles, miniatures.

All these circumstances, so painfully perceived by the easily vulnerable psyche of the artist, give in part an additional key to his nervous and refined art, help to understand where that tragic shadow falls, which is hard not to feel in his game. But the personality of Michelangeli does not always fit into the framework of the image of a “proud and sad loner”, which is entrenched in the minds of others.

No, he knows how to be simple, cheerful and friendly, which many of his colleagues can tell about, he knows how to enjoy meeting with the public and remember this joy. The meeting with the Soviet audience in 1964 remained such a bright memory for him. “There, in the east of Europe,” he later said, “spiritual food still means more than material food: it is incredibly exciting to play there, listeners demand full dedication from you.” And this is exactly what an artist needs, like air.

Grigoriev L., Platek Ya., 1990