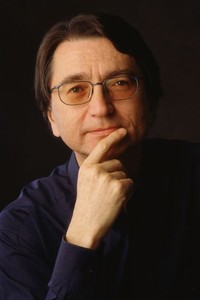

Stanislav Genrikhovich Neuhaus |

Stanislav Neuhaus

Stanislav Genrikhovich Neuhaus, the son of an outstanding Soviet musician, was ardently and devotedly loved by the public. He was always captivated by a high culture of thought and feeling – no matter what he performed, no matter what mood he was in. There are quite a few pianists who can play faster, more accurately, more spectacularly than Stanislav Neuhaus did, but in terms of the richness of psychological nuance, the refinement of musical experience, he found few equals to himself; it was once successfully said about him that his playing is a model of “emotional virtuosity.”

- Piano music in the Ozon online store →

Neuhaus was lucky: from an early age he was surrounded by an intellectual environment, he breathed the air of lively and versatile artistic impressions. Interesting people were always close to him – artists, musicians, writers. His talent was someone to notice, support, direct in the right direction.

Once, when he was about five years old, he picked up some melody from Prokofiev on the piano – he overheard it from his father. They started working with him. At first, the grandmother, Olga Mikhailovna Neigauz, a piano teacher with many years of experience, acted as a teacher; she was later replaced by the teacher of the Gnessin Music School Valeria Vladimirovna Listova. About Listova, in whose class Neuhaus spent several years, he later recalled with a sense of respect and gratitude: “He was a truly sensitive teacher … For example, from my youth I did not like the finger simulator – scales, etudes, exercises “on technique”. Valeria Vladimirovna saw this and did not try to change me. She and I knew only music – and it was wonderful … “

Neuhaus has been studying at the Moscow Conservatory since 1945. However, he entered his father’s class – the Mecca of the pianistic youth of those times – later, when he was already in his third year. Prior to that, Vladimir Sergeevich Belov worked with him.

“At first, my father did not really believe in my artistic future. But, having looked at me once at one of the student evenings, he apparently changed his mind – in any case, he took me to his class. He had a lot of students, he was always extremely overloaded with pedagogical work. I remember that I had to listen to others more often than to play myself – the line did not reach. But by the way, it was also very interesting to listen to: both new music and father’s opinion about its interpretation were recognized. His comments and remarks, to whomever they were directed, benefited the entire class.

One could often see Svyatoslav Richter in the Neuhaus house. He used to sit down at the piano and practice without leaving the keyboard for hours. Stanislav Neuhaus, an eyewitness and witness to this work, went through a kind of piano school: it was hard to wish for a better one. Richter’s classes were remembered by him forever: “Svyatoslav Teofilovich was struck by colossal perseverance in work. I would say, inhuman will. If a place did not work out for him, he fell upon it with all his energy and passion until, at last, he overwhelmed the difficulty. For those who watched him from the side, this always made a strong impression … “

In the 1950s, Neuhaus’s father and son often performed together as a piano duet. In their performance one could hear Mozart’s sonata in D major, Schumann’s Andante with variations, Debussy’s “White and Black”, Rachmaninov’s suites… father. Since graduating from the conservatory (1953), and later postgraduate studies (XNUMX), Stanislav Neuhaus has gradually established himself in a prominent place among Soviet pianists. With him met after the domestic and foreign audience.

As already mentioned, Neuhaus was close to the circles of the artistic intelligentsia from childhood; he spent many years in the family of the outstanding poet Boris Pasternak. Poems resounded around him. Pasternak himself liked to read them, and his guests, Anna Akhmatova and others, also read them. Perhaps the atmosphere in which Stanislav Neuhaus lived, or some innate, “immanent” properties of his personality, had an effect – in any case, when he entered the concert stage, the public immediately recognized him as About this, and not a prose writer, of which there were always many among his colleagues. (“I listened to poetry from childhood. Probably, as a musician, it gave me a lot …,” he recalled.) The natures of his warehouse – subtle, nervous, spiritual – most often close to the music of Chopin, Scriabin. Neuhaus was one of the best Chopinists in our country. And as it was rightly considered, one of the born interpreters of Scriabin.

He was usually rewarded with warm applause for playing Barcarolle, Fantasia, waltzes, nocturnes, mazurkas, Chopin ballads. Scriabin’s sonatas and lyrical miniatures – “Fragility”, “Desire”, “Riddle”, “Weasel in the Dance”, preludes from various opuses, enjoyed great success at his evenings. “Because it is true poetry” (Andronikov I. To music. – M., 1975. P. 258.), – as Irakli Andronikov rightly noted in the essay “Neigauz Again”. Neuhaus the concert performer had one more quality that made him an excellent interpreter of precisely the repertoire that had just been named. Quality, the essence of which finds the most precise expression in the term music making.

While playing, Neuhaus seemed to be improvising: the listener felt the live flow of the performer’s musical thought, not constrained by clichés – its variability, the exciting unexpectedness of angles and turns. The pianist, for example, often took to the stage with Scriabin’s Fifth Sonata, with etudes (Op. 8 and 42) by the same author, with Chopin’s ballads – each time these works looked somehow different, in a new way … He knew how to play unequally, bypassing stencils, playing music a la impromptu – what could be more attractive in a concertante? It was said above that in the same manner, freely and improvisationally, V. V. Sofronitsky, who was deeply revered by him, played music on the stage; his own father played in the same stage vein. Perhaps it would be difficult to name a pianist closer to these masters in terms of performance than Neuhaus Jr.

It was said on the previous pages that the improvisational style, for all its charms, is fraught with certain risks. Along with creative successes, misfires are also possible here: what came out yesterday may well not work out today. Neuhaus – what to hide? – was convinced (more than once) of the fickleness of artistic fortune, he was familiar with the bitterness of stage failure. Regulars of concert halls remember difficult, almost emergency situations at his performances – moments when the original law of performance, formulated by Bach, began to be violated: in order to play well, you need to press the right key with the right finger at the right time … This happened with Neuhaus and in Chopin’s Twenty-fourth Etude , and in Scriabin’s C-sharp minor (Op. 42) etude, and Rachmaninov’s G-minor (Op. 23) prelude. He was not classified as a solid, stable performer, but—isn’t it paradoxical?—the vulnerability of Neuhaus’s craft as a concert performer, his slight “vulnerability” had its own charm, its own charm: only the living is vulnerable. There are pianists who erect indestructible blocks of musical form even in Chopin’s mazurkas; fragile sonic moments of Scriabin or Debussy — and they harden under their fingers like reinforced concrete. Neuhaus’ play was an example of the exact opposite. Perhaps, in some ways he lost (he suffered “technical losses”, in the language of reviewers), but he won, and in an essential (I remember that in a conversation between Moscow musicians, one of them said, “You must admit, Neuhaus knows how to play a little…” A little? few know how to do it at the piano. what he can do. And that’s the main thing…”.

Neuhaus was known not only for the clavirabends. As a teacher, he once assisted his father, from the beginning of the sixties he became the head of his own class at the conservatory. (Among his students are V. Krainev, V. Kastelsky, B. Angerer.) From time to time he traveled abroad for pedagogical work, held so-called international seminars in Italy and Austria. “Usually these trips take place during the summer months,” he said. “Somewhere, in one of the European cities, young pianists from different countries gather. I select a small group, about eight or ten people, from those who seem to me worthy of attention, and begin to study with them. The rest are just present, watching the course of the lesson with notes in their hands, going through, as we would say, passive practice.

Once one of the critics asked him about his attitude to pedagogy. “I love teaching,” Neuhaus replied. “I love being among young people. Although … You have to give a lot of energy, nerves, strength another time. You see, I can’t listen to “non-music” in class. I’m trying to achieve something, achieve … Sometimes impossible with this student. In general, pedagogy is hard love. Still, I would like to feel first of all a concert performer.”

The rich erudition of Neuhaus, his peculiar approach to the interpretation of musical works, many years of stage experience – all this was of value, and considerable, for the creative youth around him. He had a lot to learn, a lot to learn. Perhaps, first of all, in the art of the piano sounding. An art in which he knew few equals.

He himself, when he was on the stage, had a wonderful piano sound: this was almost the strongest side of his performance; nowhere did the aristocracy of his artistic nature come to light with such obviousness as in sound. And not only in the “golden” part of his repertoire – Chopin and Scriabin, where one simply cannot do without the ability to choose an exquisite sound outfit – but also in any music he interprets. Let us recall, for example, his interpretations of Rachmaninoff’s E-flat major (Op. 23) or F-minor (Op. 32) preludes, Debussy’s piano watercolors, plays by Schubert and other authors. Everywhere the pianist’s playing captivated with the beautiful and noble sound of the instrument, the soft, almost unstressed manner of performance, and the velvety coloring. Everywhere you could see affectionate (you can’t say otherwise) attitude to the keyboard: only those who really love the piano, its original and unique voice, play music this way. There are quite a few pianists who demonstrate a good culture of sound in their performances; there are much fewer of those who listen to the instrument by itself. And there are not many artists with an individual timbre coloring of sound inherent to them alone. (After all, Piano Masters — and only they! — have a different sound palette, just as different light, color and coloring of great painters.) Neuhaus had his own, special piano, it could not be confused with any other.

… A paradoxical picture is sometimes observed in a concert hall: a performer who has received many awards at international competitions in his time, finds interested listeners with difficulty; at the performances of the other, who has far fewer regalia, distinctions and titles, the hall is always full. (They say it’s true: competitions have their own laws, concert audiences have their own.) Neuhaus did not have a chance to win competitions with his colleagues. Nevertheless, the place that he occupied in the philharmonic life gave him a visible advantage over many experienced competitive fighters. He was widely popular, tickets for his clavirabends were sometimes asked even on the distant approaches to the halls where he performed. He had what every touring artist dreams of: its audience. It seems that in addition to the qualities that have already been mentioned – the peculiar lyricism, charm, intelligence of Neuhaus as a musician – something else made itself felt that aroused people’s sympathy for him. He, as far as it is possible to judge from the outside, was not too concerned about the search for success …

A sensitive listener immediately recognizes this (the delicacy of the artist, stage altruism) – as they recognize, and immediately, any manifestations of vanity, posture, stage self-display. Neuhaus did not try at all costs to please the public. (I. Andronikov writes well: “In the huge hall, Stanislav Neuhaus remains as if alone with the instrument and with the music. As if there is no one in the hall. And he plays Chopin as if for himself. As his own, deeply personal…” (Andronikov I. To music. S. 258)) This was not refined coquetry or professional reception – this was a property of his nature, character. This was probably the main reason for his popularity with listeners. “… The less a person is imposed on other people, the more others are interested in a person,” the great stage psychologist Stanislavsky assured, deducing from this that “as soon as an actor ceases to reckon with the crowd in the hall, she herself begins to reach out to him (Stanislavsky K. S. Sobr. soch. T. 5. S. 496. T. 1. S. 301-302.). Fascinated by music, and only by it, Neuhaus had no time for worries about success. The more true he came to him.

G. Tsypin