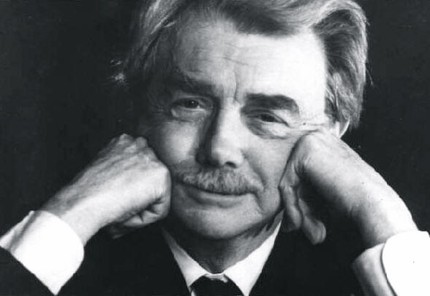

Heinrich Gustavovich Neuhaus |

Heinrich Neuhaus

Heinrich Gustavovich Neuhaus was born on April 12, 1888 in Ukraine, in the city of Elisavetgrad. His parents were well-known musicians-teachers in the city, who founded a music school there. Henry’s maternal uncle was a wonderful Russian pianist, conductor and composer F.M. Blumenfeld, and his cousin – Karol Szymanowski, later an outstanding Polish composer.

The boy’s talent manifested itself very early, but, oddly enough, in childhood he did not receive a systematic musical education. His pianistic development proceeded largely spontaneously, obeying the mighty power of the music that sounded in him. “When I was about eight or nine years old,” Neuhaus recalled, “I began to improvise on the piano a little at first, and then more and more and more and more, the more passionately I improvised on the piano. Sometimes (this was a little later) I reached the point of complete obsession: I didn’t have time to wake up, as I already heard music inside myself, my music, and so almost all day.

At the age of twelve, Henry made his first public appearance in his hometown. In 1906, the parents sent Heinrich and his older sister Natalia, also a very good pianist, to study abroad in Berlin. On the advice of F.M. Blumenfeld and A.K. Glazunov’s mentor was the famous musician Leopold Godovsky.

However, Heinrich took only ten private lessons from Godowsky and disappeared from his field of vision for almost six years. The “years of wandering” began. Neuhaus eagerly absorbed everything that the culture of Europe could give him. The young pianist gives concerts in the cities of Germany, Austria, Italy, Poland. Neuhaus is warmly received by the public and press. The reviews note the scale of his talent and express the hope that the pianist will eventually take a prominent place in the musical world.

“At sixteen or seventeen years old, I began to “reason”; the ability to comprehend, to analyze woke up, I put all my pianism, all my pianistic economy into question,” recalls Neuhaus. “I decided that I didn’t know either the instrument or my body, and I had to start all over again. For months (!) I began to play the simplest exercises and etudes, starting with five fingers, with only one goal: to adapt my hand and fingers entirely to the laws of the keyboard, to implement the principle of economy to the end, to play “rationally”, as the pianola is rationally arranged; of course, my exactingness in the beauty of sound was brought to the maximum (I always had a good and thin ear) and this was probably the most valuable thing at all the time when I, with a manic obsession, tried only to extract the “best sounds” from the piano, and music, living art, literally locked it at the bottom of the chest and did not get it out for a long, long time (the music continued its life outside the piano).

Since 1912, Neuhaus again began to study with Godowsky at the School of Masters at the Vienna Academy of Music and Performing Arts, which he graduated with brilliance in 1914. Throughout his life, Neuhaus recalled his teacher with great warmth, describing him as one of “the great virtuoso pianists of the post-Rubinstein era.” The outbreak of the First World War excited the musician: “In the event of mobilization, I had to go as a simple private. Combining my last name with a diploma from the Vienna Academy did not bode well. Then we decided at the family council that I needed to get a diploma from the Russian Conservatory. After various troubles (I nevertheless smelled the military service, but was soon released with a “white ticket”), I went to Petrograd, in the spring of 1915 I passed all the exams at the conservatory and received a diploma and the title of “free artist”. One fine morning at F.M. Blumenfeld, the phone rang: the director of the Tiflis branch of the IRMO Sh.D. Nikolaev with a proposal that I come from the autumn of this year to teach in Tiflis. Without thinking twice, I agreed. Thus, from October 1916, for the first time, I completely “officially” (since I started working in a state institution) took the path of a Russian music teacher and pianist-performer.

After a summer spent partly in Timoshovka with the Shimanovskys, partly in Elisavetgrad, I arrived in Tiflis in October, where I immediately began working at the future conservatory, which was then called the Musical School of the Tiflis Branch and the Imperial Russian Musical Society.

The students were the weakest, most of them in our time could hardly be accepted into the regional music school. With very few exceptions, my work was the same “hard labor” that I had tasted back in Elisavetgrad. But a beautiful city, the south, some pleasant acquaintances, etc. partially rewarded me for my professional suffering. Soon I began to perform solo concerts, in symphony concerts and ensembles with my colleague violinist Evgeny Mikhailovich Guzikov.

From October 1919 to October 1922 I was a professor at the Kyiv Conservatory. Despite the heavy teaching load, over the years I have given many concerts with a variety of programs (from Bach to Prokofiev and Shimanovsky). B.L. Yavorsky and F.M. Blumenfeld then also taught at the Kyiv Conservatory. In October, F.M. Blumenfeld and I, at the request of People’s Commissar A.V. Lunacharsky, were transferred to the Moscow Conservatory. Yavorsky had moved to Moscow a few months before us. Thus began the “Moscow period of my musical activity.”

So, in the fall of 1922, Neuhaus settled in Moscow. He plays in both solo and symphony concerts, performs with the Beethoven Quartet. First with N. Blinder, then with M. Polyakin, the musician gives cycles of sonata evenings. The programs of his concerts, and previously quite diverse, include works by a wide variety of authors, genres and styles.

“Who in the twenties and thirties listened to these speeches by Neuhaus,” writes Ya.I. Milstein, – he acquired something for life that cannot be expressed in words. Neuhaus could play more or less successfully (he was never an even pianist – partly due to increased nervous excitability, a sharp change in mood, partly due to the primacy of the improvisational principle, the power of the moment). But he invariably attracted, inspired and inspired with his game. He was always different and at the same time the same artist-creator: it seemed that he did not perform music, but here, on the stage, he created it. There was nothing artificial, formulaic, copied in his game. He possessed amazing vigilance and spiritual clarity, inexhaustible imagination, freedom of expression, he knew how to hear and reveal everything hidden, hidden (let us recall, for example, his love for the subtext of performance: “you need to delve into the mood – after all, it is in this, barely perceptible and amenable to musical notation, the whole essence of the idea, the whole image … “). He owned the most delicate sound colors to convey the subtlest nuances of feeling, those elusive mood swings that remain inaccessible to most performers. He obeyed what he performed and creatively recreated it. He gave himself up entirely to a feeling that at times seemed boundless in him. And at the same time, he was exactingly strict with himself, being critical of every detail of performance. He himself once admitted that “the performer is a complex and contradictory being”, that “he loves what he performs, and criticizes him, and obeys him completely, and reworks him in his own way”, that “at other times, and it is no coincidence that a stern critic with prosecutorial inclinations dominates in his soul, ”but that“ in the best moments he feels that the work being performed is, as it were, his own, and he sheds tears of joy, excitement and love for him.

The pianist’s rapid creative growth was largely facilitated by his contacts with the largest Moscow musicians – K. Igumnov, B. Yavorsky, N. Myaskovsky, S. Feinberg and others. Of great importance for Neuhaus were frequent meetings with Moscow poets, artists, and writers. Among them were B. Pasternak, R. Falk, A. Gabrichevsky, V. Asmus, N. Wilmont, I. Andronikov.

In the article “Heinrich Neuhaus”, published in 1937, V. Delson writes: “There are people whose profession is completely inseparable from their life. These are enthusiasts of their work, people of vigorous creative activity, and their life path is a continuous creative burning. Such is Heinrich Gustavovich Neuhaus.

Yes, and Neuhaus’s playing is the same as he is – stormy, active, and at the same time organized and thought out to the last sound. And at the piano, the sensations that arise in Neuhaus seem to “overtake” the course of his performance, and impatiently demanding, imperiously exclamatory accents burst into his playing, and everything (exactly everything, and not just tempos!) In this game is uncontrollably swift, filled with proud and daring “motivation,” as I. Andronikov very aptly once said.

In 1922, an event occurred that determined the entire future creative fate of Neuhaus: he became a professor at the Moscow Conservatory. For forty-two years, his pedagogical activity continued at this illustrious university, which gave remarkable results and in many ways contributed to the wide recognition of the Soviet piano school throughout the world. In 1935-1937, Neuhaus was director of the Moscow Conservatory. In 1936-1941 and from 1944 until his death in 1964, he was the head of the Department of Special Piano.

Only in the terrible years of the Great Patriotic War, he was forced to suspend his teaching activities. “In July 1942, I was sent to Sverdlovsk to work at the Ural and Kyiv (temporarily evacuated to Sverdlovsk) conservatories,” Genrikh Gustavovich writes in his autobiography. – I stayed there until October 1944, when I was returned to Moscow, to the conservatory. During my stay in the Urals (besides energetic teaching work), I gave many concerts in Sverdlovsk itself and in other cities: Omsk, Chelyabinsk, Magnitogorsk, Kirov, Sarapul, Izhevsk, Votkinsk, Perm.

The romantic beginning of the musician’s artistry was also reflected in his pedagogical system. At his lessons, a world of winged fantasy reigned, liberating the creative forces of young pianists.

Beginning in 1932, numerous pupils of Neuhaus won prizes at the most representative all-Union and international piano competitions – in Warsaw and Vienna, Brussels and Paris, Leipzig and Moscow.

The Neuhaus school is a powerful branch of modern piano creativity. What different artists came out from under his wing – Svyatoslav Richter, Emil Gilels, Yakov Zak, Evgeny Malinin, Stanislav Neigauz, Vladimir Krainev, Alexei Lyubimov. Since 1935, Neuhaus regularly appeared in the press with articles on topical issues in the development of musical art, and reviewed concerts by Soviet and foreign musicians. In 1958, his book “On the Art of Piano Playing” was published in Muzgiz. Notes of a teacher”, which was repeatedly reprinted in subsequent decades.

“In the history of Russian pianistic culture, Heinrich Gustavovich Neuhaus is a rare phenomenon,” writes Ya.I. Milstein. – His name is associated with the idea of the daring of thought, the fiery ups of feeling, the amazing versatility and at the same time the integrity of nature. Anyone who has experienced the power of his talent, it is difficult to forget his truly inspired game, which gave people so much pleasure, joy and light. Everything external receded into the background before the beauty and significance of the inner experience. There were no empty spaces, templates and stamps in this game. She was full of life, spontaneity, captivated not only with clarity of thought and conviction, but also with genuine feelings, extraordinary plasticity and relief of musical images. Neuhaus played extremely sincerely, naturally, simply, and at the same time extremely passionately, passionately, selflessly. Spiritual impulse, creative upsurge, emotional burning were integral qualities of his artistic nature. Years passed, a lot of things grew old, became faded, dilapidated, but his art, the art of a musician-poet, remained young, temperamental and inspired.