Seriality, serialism |

French musique serielle, German. serielle Musik – serial, or serial, music

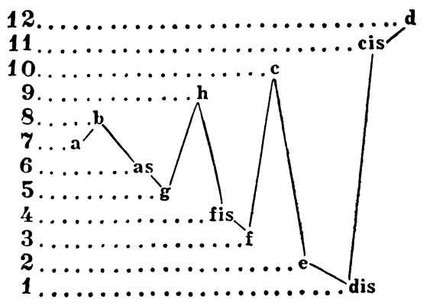

One of the varieties of serial technology, with which a series of decomp. parameters, eg. series of pitches and rhythm or pitches, rhythm, dynamics, articulation, agogics and tempo. S. should be distinguished from polyseries (where two or more series of one, usually high-altitude, parameter are used) and from seriality (which means the use of serial technique in the broad sense, as well as the technique of only a high-altitude series). An example of one of the simplest types of S.’s technique: the succession of pitches is regulated by a series chosen by the composer (pitch), and the duration of sounds is regulated by a series of durations freely chosen or derived from a pitch series (i.e., a series of another parameter). Thus, a series of 12 pitches can be turned into a series of 12 durations – 7, 8, 6, 5, 9, 4, 3, 10, 2, 1, 11, 12, imagining that each digit indicates the number of sixteenths (eighths, thirty-seconds) in the given duration:

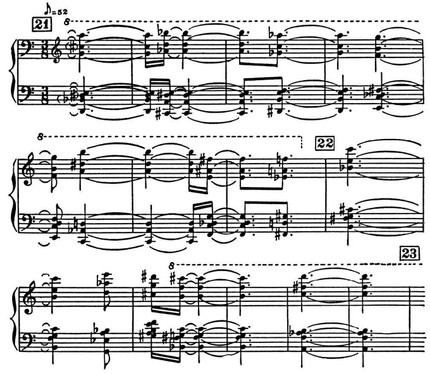

When a pitch series is superimposed on a rhythmic one, not a serial, but a serial fabric arises:

A. G. Schnittke. Concerto No 2 for violin and orchestra.

S. arose as an extension of the principles of serial technique (high-pitched series) to other parameters that remained free: duration, register, articulation, timbre, etc. At the same time, the question of the relationship between parameters arises in a new way: in the organization of music. material, the role of numerical progressions, numerical proportions increases (for example, in the 3rd part of E. V. Denisov’s cantata “The Sun of the Incas”, the so-called organizing numbers are used – 6 sounds of the series, 6 dynamic. shades, 6 timbres). There is a tendency towards the consistent and total use of the entire range of means of each of the parameters or to “interchromatic”, i.e. to the merging of different parameters – harmony and timbre, pitch and duration (the latter is conceived as a correspondence of numerical structures, proportions; see the example above) . K. Stockhausen put forward the idea of joining 2 aspects of muses. time – microtime, represented by the pitch of the sound, and macrotime, represented by its duration, and accordingly stretched both into one line, dividing the area of durations into “long octaves” (Dauernoktaven; pitch octaves, where the pitches are related as 2: 1, continue in long octaves , where the durations are related in the same way). The transition to even larger time units denotes relationships that develop into muses. form (where the manifestation of the 2:1 ratio is the ratio of squareness). The extension of the principle of seriality to all the parameters of music is called total symphony (an example of multidimensional symphony is Stockhausen’s Groups for Three Orchestras, 1957). However, the action of even the same series in different parameters is not perceived as identical, therefore the relationship of the parameters with each other b. h. turns out to be a fiction, and the increasingly strict organization of parameters, especially with total S., in fact means a growing danger of incoherence and chaos, the automatism of the composition process, and the loss of the composer’s auditory control over his work. P. Boulez warned against “replacing the work with organization.” Total S. means the end of the very original idea of the series and serialization, leads to a seemingly unexpected transition into the field of free, intuitive music, opens the way to aleatorics and electronics (technical music; see Electronic music).

One of the first experiences S. can be considered strings. trio by E. Golyshev (published in 1925), where, in addition to 12-tone complexes, rhythmic was used. row. A. Webern came to the idea of S., who, however, was not a serialist in the exact sense of the word; in a number of serial works. he uses complement. organizing means – register (for example, in the 1st part of the symphony op. 21), dynamic-articulatory (“Variations” for piano op. 27, 2nd part), rhythmic (quasi-series of rhythm 2, 2, 1 , 2 in “Variations” for orchestra, op.30). Consciously and consistently S. applied O. Messiaen in “4 rhythmic studies” for piano. (e.g., in Fire Island II, No 4, 1950). Further, Boulez turned to S. (“Polyphony X” for 18 instruments, 1951, “Structures”, 1a, for 2 fp., 1952), Stockhausen (“Cross Play” for an ensemble of instruments, 1952; “Counterpoints” for an ensemble of instruments, 1953; Groups for three orchestras, 1957), L. Nono (Meetings for 24 instruments, 1955, cantata Interrupted Song, 1956), A. Pusser (Webern Memory Quintet, 1955), and others. in production owls. composers, for example. by Denisov (No 4 from the vocal cycle “Italian Songs”, 1964, No 3 from “5 Stories about Mr. Keuner” for voice and ensemble of instruments, 1966), A. A. Pyart (2 parts from 1 and 2 th symphony, 1963, 1966), A. G. Schnittke (“Music for chamber orchestra”, 1964; “Music for piano and chamber orchestra”, 1964; “Pianissimo” for orchestra, 1968).

References: Denisov E. V., Dodecaphony and problems of modern composing technique, in: Music and Modernity, vol. 6, M., 1969; Shneerson G. M., Serialism and aleatorics – “the identity of opposites”, “SM”, 1971; no 1; Stockhausen K., Weberns Konzert für 9 Instrumente op. 24, “Melos”, 1953, Jahrg. 20, H. 12, the same, in his book: Texte…, Bd l, Köln, (1963); his own, Musik im Raum, in the book: Darmstädter Beiträge zur neuen Musik, Mainz, 1959, (H.) 2; of his own, Kadenzrhythmik bei Mozart, ibid., 1961, (H.) 4 (Ukrainian translation – Stockhausen K., Rhythmichni kadansi by Mozart, in collection: Ukrainian musicology, v. 10, Kipv, 1975, p. 220 -71); his own, Arbeitsbericht 1952/53: Orientierung, in his book: Texte…, Bd 1, 1963; Gredinger P., Das Serielle, in Die Reihe, 1955, (H.) 1; Pousseur H., Zur Methodik, ibid., 1957, (H.) 3; Krenek E., Was ist “Reihenmusik”? “NZfM”, 1958, Jahrg. 119, H. 5, 8; his own, Bericht über Versuche in total determinierter Musik, “Darmstädter Beiträge”, 1958, (H.) 1; his, Extents and limits of serial techniques “MQ”, 1960, v. 46, No 2. Ligeti G., Pierre Boulez: Entscheidung und Automatik in der Structure Ia, in Die Reihe, 1958, (N.) 4 of the same, Wandlungen der musikalischen Form, ibid., 1960, (H. ) 7; Nono L., Die Entwicklung der Reihentechnik, “Darmstädter Beiträge”, 1958, (H.) 1; Schnebel D., Karlheinz Stockhausen, in Die Reihe, 1958, (H.) 4; Eimert H., Die zweite Entwicklungsphase der Neuen Musik, Melos, 1960, Jahrg. 27, H. 12; Zeller HR, Mallarmé und das serielle Denken, in Die Reihe, 11, (H.) 1960; Wolff Chr., Ber Form, ibid., 6, (H.) 1960; Buyez P., Die Musikdenken heute 7, Mainz – L. – P. – NY, (1); Kohoutek C., Novodobé skladebné teorie zbpadoevropské hudby, Praha, 1, under the title: Novodobé skladebné smery n hudbl, Praha, 1963 (Russian translation — Kohoutek Ts., Technique of Composition in Music of the 1962th Century, M., 1965); Stuckenschmidt HH, Zeitgenössische Techniken in der Musik, “SMz”, 1976, Jahrg. 1963; Westergaard P., Webern and “Total organization”: an analysis of the second movement of Piano Variations, op. 103, “Perspectives of new music”, NY – Princeton, 27 (v. 1963, No 1); Heinemann R., Untersuchungen zur Rezeption der seriellen Musik, Regensburg, 2; Deppert H., Studien zur Kompositionstechnik im instrumentalen Spätwerk Anton Weberns, (Darmstadt, 1966); Stephan R., Bber Schwierigkeiten der Bewertung und der Analyze neuester Musik, “Musica”, 1972, Jahrg 1972, H. 26; Vogt H., Neue Musik seit 3, Stuttg., (1945); Fuhrmann R., Pierre Boulez (1972), Structures 1925 (1), in Perspektiven neuer Musik, Mainz. (1952); Karkoschka E., Hat Webern seriell komponiert?, TsMz, 1974, H. 1975; Oesch H., Pioniere der Zwölftontechnik, in Forum musicologicum, Bern, (11).

Yu. H. Kholopov