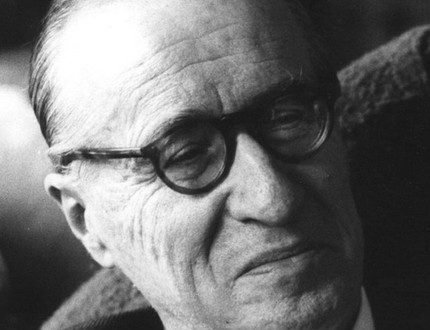

Rodion Konstantinovich Shchedrin |

Rodion Shchedrin

Oh, be our keeper, savior, music! Don’t leave us! wake up our mercantile souls more often! strike sharper with your sounds on our dormant senses! Agitate, tear them apart and drive them away, even if only for a moment, this coldly terrible egoism that is trying to take over our world! N. Gogol. From the article “Sculpture, painting and music”

In the spring of 1984, in one of the concerts of the II International Music Festival in Moscow, the premiere of “Self-portrait” – variations for a large symphony orchestra by R. Shchedrin was performed. The new composition of the musician, who has just crossed the threshold of his fiftieth birthday, burned some with a piercing emotional statement, others excited with the journalistic bareness of the theme, the ultimate concentration of thoughts about his own destiny. It is truly true that it is said: “the artist is his own supreme judge.” In this one-part composition, equal in significance and content to a symphony, the world of our time appears through the prism of the artist’s personality, presented in close-up, and through it is known in all its versatility and contradictions – in active and meditative states, in contemplation, lyrical self-deepening, in moments jubilation or tragic explosions filled with doubt. To “Self-portrait”, and it is natural, threads are pulled together from many works previously written by Shchedrin. As if from a bird’s eye view, his creative and human path appears – from the past to the future. The path of “darling of fate”? Or “martyr”? In our case, it would be wrong to say neither one nor the other. It is closer to the truth to say: the path of the daring “from the first person” …

Shchedrin was born into a musician’s family. Father, Konstantin Mikhailovich, was a famous musicologist lecturer. Music was constantly played in the Shchedrins’ house. It was live music-making that was the breeding ground that gradually formed the passions and tastes of the future composer. The family pride was the piano trio, in which Konstantin Mikhailovich and his brothers participated. The years of adolescence coincided with a great trial that fell on the shoulders of the entire Soviet people. Twice the boy fled to the front and twice was returned to his parents’ house. Later Shchedrin will remember the war more than once, more than once the pain of what he experienced will echo in his music – in the Second Symphony (1965), choirs to poems by A. Tvardovsky – in memory of a brother who did not return from the war (1968), in “Poetoria” (at st. A. Voznesensky, 1968) – an original concerto for the poet, accompanied by a female voice, a mixed choir and a symphony orchestra …

In 1945, a twelve-year-old teenager was assigned to the recently opened Choir School – now them. A. V. Sveshnikova. In addition to studying theoretical disciplines, singing was perhaps the main occupation of the pupils of the school. Decades later, Shchedrin would say: “I experienced the first moments of inspiration in my life while singing in the choir. And of course, my first compositions were also for the choir…” The next step was the Moscow Conservatory, where Shchedrin studied simultaneously at two faculties – in composition with Y. Shaporin and in the piano class with Y. Flier. A year before graduation, he wrote his First Piano Concerto (1954). This early opus attracted with its originality and lively emotional current. The twenty-two-year-old author dared to include 2 ditty motifs in the concert-pop element – the Siberian “Balalaika is buzzing” and the famous “Semyonovna”, effectively developing them in a series of variations. The case is almost unique: Shchedrin’s first concert not only sounded in the program of the next composers’ plenum, but also became the basis for admitting a 4th year student … to the Union of Composers. Having brilliantly defended his diploma in two specialties, the young musician improved himself in graduate school.

At the beginning of his journey, Shchedrin tried out different areas. These were the ballet by P. Ershov The Little Humpbacked Horse (1955) and the First Symphony (1958), the Chamber Suite for 20 violins, harp, accordion and 2 double basses (1961) and the opera Not Only Love (1961), a satirical resort cantata “Bureaucratiada” (1963) and Concerto for orchestra “Naughty ditties” (1963), music for drama performances and films. The merry march from the film “Vysota” instantly became a musical bestseller… The opera based on the story by S. Antonov “Aunt Lusha” stands out in this series, the fate of which was not easy. Turning to history, scorched by misfortune, to the images of simple peasant women doomed to loneliness, the composer, according to his confession, deliberately focused on the creation of a “quiet” opera, as opposed to the “monumental performances with grandiose extras” staged then, in the early 60s. , banners, etc.” Today it is impossible not to regret that in its time the opera was not appreciated and was not understood even by professionals. Criticism noted only one facet – humor, irony. But in essence, the opera Not Only Love is the brightest and perhaps the first example in Soviet music of the phenomenon that later received the metaphorical definition of “village prose”. Well, the way ahead of time is always thorny.

In 1966, the composer will begin work on his second opera. And this work, which included the creation of his own libretto (here Shchedrin’s literary gift manifested itself), took a decade. “Dead Souls”, opera scenes after N. Gogol – this is how this grandiose idea took shape. And unconditionally was appreciated by the musical community as innovative. The composer’s desire to “read Gogol’s singing prose by means of music, to outline the national character with music, and to emphasize the infinite expressiveness, liveliness and flexibility of our native language with music” was embodied in the dramatic contrasts between the frightening world of dealers in dead souls, all these Chichikovs, Sobeviches, Plyushkins, boxes, manilovs, who ruthlessly scourged in the opera, and the world of “living souls”, folk life. One of the themes of the opera is based on the text of the same song “Snow is not white”, which is mentioned more than once by the writer in the poem. Relying on the historically established opera forms, Shchedrin boldly rethinks them, transforms them on a fundamentally different, truly modern basis. The right to innovate is provided by the fundamental properties of the individuality of the artist, firmly based on a thorough knowledge of the traditions of the richest and unique in its achievements of domestic culture, on blood, tribal involvement in folk art – its poetics, melos, various forms. “Folk art evokes a desire to recreate its incomparable aroma, to somehow “correlate” with its wealth, to convey the feelings it gives rise to that cannot be formulated in words,” the composer claims. And above all, his music.

This process of “recreating the folk” gradually deepened in his work – from the elegant stylization of folklore in the early ballet “The Little Humpbacked Horse” to the colorful sound palette of Mischievous Chastushkas, the dramatically harsh system of “Rings” (1968), resurrecting the strict simplicity and volume of Znamenny chants; from the embodiment in music of a brightly genre portrait, a strong image of the main character of the opera “Not Only Love” to a lyrical narration about the love of ordinary people for Ilyich, about their personal innermost attitude to “the most earthly of all people who have passed through the earth” in the oratorio “Lenin in the Heart folk “(1969) – the best, we agree with the opinion of M. Tarakanov,” the musical embodiment of the Leninist theme, which appeared on the eve of the 100th anniversary of the leader’s birth. From the pinnacle of creating the image of Russia, which certainly was the opera “Dead Souls”, staged by B. Pokrovsky in 1977 on the stage of the Bolshoi Theater, the arch is thrown to “The Sealed Angel” – choral music in 9 parts according to N. Leskov (1988). As the composer notes in the annotation, he was attracted by the story of the icon painter Sevastyan, “who printed an ancient miraculous icon defiled by the powerful of this world, first of all, the idea of the imperishability of artistic beauty, the magical, uplifting power of art.” “The Captured Angel”, as well as a year earlier created for the symphony orchestra “Stikhira” (1987), based on the Znamenny chant, are dedicated to the 1000th anniversary of the baptism of Russia.

Leskov’s music logically continued a number of Shchedrin’s literary predilections and affections, emphasizing his principled orientation: “… I cannot understand our composers who turn to translated literature. We have untold wealth – literature written in Russian. In this series, a special place is given to Pushkin (“one of my gods”) – in addition to the early two choirs, in 1981 the choral poems “The Execution of Pugachev” were created on the prose text from the “History of the Pugachev Rebellion” and “Strophes of “Eugene Onegin””.

Thanks to musical performances based on Chekhov – “The Seagull” (1979) and “Lady with a Dog” (1985), as well as previously written lyrical scenes based on the novel by L. Tolstoy “Anna Karenina” (1971), the gallery of those embodied on the ballet stage was significantly enriched Russian heroines. The true co-author of these masterpieces of modern choreographic art was Maya Plisetskaya, an outstanding ballerina of our time. This community – creative and human – is already over 30 years old. Whatever Shchedrin’s music tells about, each of his compositions carries a charge of active search and reveals the features of a bright individuality. The composer keenly feels the pulse of time, sensitively perceiving the dynamics of today’s life. He sees the world in volume, grasping and capturing in artistic images both a specific object and the entire panorama. Could this be the reason for his fundamental orientation towards the dramatic method of montage, which makes it possible to more clearly outline the contrasts of images and emotional states? Based on this dynamic method, Shchedrin strives for conciseness, conciseness (“to put code information into the listener”) of the presentation of the material, for a close relationship between its parts without any connecting links. So, the Second Symphony is a cycle of 25 preludes, the ballet “The Seagull” is built on the same principle; The Third Piano Concerto, like a number of other works, consists of a theme and a series of its transformations in various variations. The lively polyphony of the surrounding world is reflected in the composer’s predilection for polyphony – both as a principle of organizing musical material, a manner of writing, and as a type of thinking. “Polyphony is a method of existence, for our life, modern existence has become polyphonic.” This idea of the composer is confirmed practically. While working on Dead Souls, he simultaneously created the ballets Carmen Suite and Anna Karenina, the Third Piano Concerto, the Polyphonic Notebook of twenty-five preludes, the second volume of 24 preludes and fugues, Poetoria, and other compositions. accompanied by Shchedrin’s performances on the concert stage as a performer of his own compositions – a pianist, and from the beginning of the 80s. and as an organist, his work is harmoniously combined with energetic public deeds.

Shchedrin’s path as a composer is always overcoming; everyday, stubborn overcoming of the material, which in the firm hands of the master turns into musical lines; overcoming the inertia, and even bias of the listener’s perception; finally, overcoming oneself, more precisely, repeating what has already been discovered, found, tested. How not to recall here V. Mayakovsky, who once remarked about chess players: “The most brilliant move cannot be repeated in a given situation in a subsequent game. Only the unexpectedness of the move knocks down the enemy.

When the Moscow audience was first introduced to The Musical Offering (1983), the reaction to Shchedrin’s new music was like a bombshell. The controversy did not subside for a long time. The composer, in his work, striving for the utmost conciseness, aphoristic expression (“telegraphic style”), suddenly seemed to have moved into a different artistic dimension. His single-movement composition for organ, 3 flutes, 3 bassoons and 3 trombones lasts… more than 2 hours. She, according to the author’s intention, is nothing more than a conversation. And not a chaotic conversation that we sometimes have, not listening to each other, in a hurry to express our personal opinion, but a conversation when everyone could tell about their sorrows, joys, troubles, revelations … “I believe that with the haste of our life, this is extremely important. Stop and think.” Let us recall that the “Musical Offering” was written on the eve of the 300th anniversary of the birth of J.S. Bach (the “Echo Sonata” for violin solo – 1984 is also dedicated to this date).

Has the composer changed his creative principles? Rather, on the contrary: with his own many years of experience in various fields and genres, he deepened what he had won. Even in his younger years, he did not seek to surprise, did not dress up in other people’s clothes, “did not run around the stations with a suitcase after the departing trains, but developed in the way … it was laid down by genetics, inclinations, likes and dislikes.” By the way, after the “Musical Offering” the proportion of slow tempos, the tempo of reflection, in Shchedrin’s music increased significantly. But there are still no empty spaces in it. As before, it creates a field of high meaning and emotional tension for perception. And responds to the strong radiation of time. Today, many artists are worried about a clear devaluation of true art, a tilt towards entertainment, simplification, and general accessibility, which testify to the moral and aesthetic impoverishment of people. In this situation of “discontinuity of culture”, the creator of artistic values becomes at the same time their preacher. In this regard, Shchedrin’s experience and his own work are vivid examples of the connection of times, “different musics”, and the continuity of traditions.

Being perfectly aware that pluralism of views and opinions is a necessary basis for life and communication in the modern world, he is an active supporter of dialogue. Very instructive are his meetings with a wide audience, with young people, in particular with fierce adherents of rock music – they were broadcast on Central Television. An example of an international dialogue initiated by our compatriot was the first in the history of Soviet-American cultural relations festival of Soviet music in Boston under the motto: “Making music together”, which unfolded a wide and colorful panorama of the work of Soviet composers (1988).

In dialogue with people with different opinions, Rodion Shchedrin always has his own point of view. In deeds and deeds – their own artistic and human conviction under the sign of the main thing: “You can’t live only for today. We need cultural construction for the future, for the benefit of future generations.”

A. Grigorieva