Phrase |

from the Greek prasis – expression, way of expression

1) Any small relatively complete musical turnover.

2) In the study of musical form, a construction that occupies an intermediate position between motive and sentence.

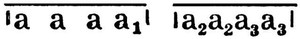

Representing a separate unit of music. speech, F. is separated from neighboring constructions by caesura, expressed by means of melody, harmony, metrorhythm, texture, but differs from sentences and periods by relatively less completeness: if the sentence ends with a clearly pronounced harmonic. cadenza, then F. “can end on any chord with any bass” (I. V. Sposobin). It includes two or more motives, but it can also be a continuous construction, not divided or only conditionally divided into motives. The sentence, in turn, may consist not only of 2 F., but of more or less of them, or not be divided into F.

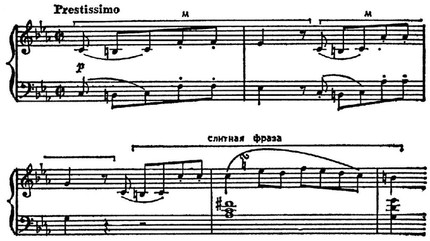

L. Beethoven. Sonata for piano, op. 7, part II.

Motive structure of phrases.

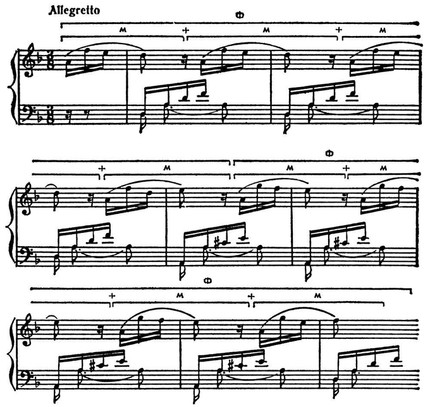

G. Rossini “The Barber of Seville”, act II, quintet.

Motive structure of phrases.

L. Beethoven. Sonata for piano, op. 10, No 1, part III.

From the point of view of the psychology of perception, F., depending on the scale and context, can be attributed to both the first (phonic) and the second (syntactic) scale levels of perception (E. Nazaikinsky, 1972).

The term “F.” was borrowed from the doctrine of verbal speech in the 18th century, when the questions of dismemberment of the muses. forms received a wide theoretical. justification as in connection with the development of a new homophonic harmonic. style, and with the tasks of performing practice – the requirement for meaningful correct phrasing. This issue acquired particular urgency in the Baroque era, because. in the dominant until the 17th century. wok. caesura’s music means. The measure was determined by the structure of the text, the ending of the verbal phrase (line), which, in turn, was associated with the length of the chant. breathing. In instr. music, which developed rapidly in the 17-18 centuries, the performer in matters of phrasing could rely only on his own. arts. flair.

L. Beethoven. Sonata for piano, op. 31. No 2, part III.

Motive structure of phrases.

M. I. Glinka. “Ivan Susanin”, Vanya’s song.

This fact was noted by F. Couperin, who in the preface to the 3rd notebook “Pièces de Clavecin” (1722) first used the term “F.” to designate a small structural unit of music. speech, emphasizing that it can be delimited by more than a pause, and introducing a special character (‘) to delimit phrases. A broader theoretical development of questions of dismemberment of muses. speeches received in the works of I. Mattezona. “Music dictionary” Ж. G. Rousseau (R., 1768) defines F. as “an uninterrupted harmonic or melodic progression which has a more or less complete meaning and ends with a stop at a more or less perfect cadenza”. AND. Mattezon, I. A. AP Schultz and J. Kirnberger expressed the idea of several stages of unification of constructions from small to larger ones. G. TO. Koch put forward a number of positions on the structure of the muses that have become classic. speech. In his works, a more accurate delimitation of the scale units of the muses appears. speech and awareness of the internal division of a 4-bar sentence into the smallest one-bar constructions, which he calls “unvollkommenen Einschnitten”, and larger two-bar structures, formed from one-bar ones, or indivisible ones, defined as “vollkommenen Einschnitten”. At 19 in. understanding F. as a two-bar structure, intermediate between a one-bar motif and a 4-bar sentence, becomes characteristic of the traditions. music theory (L. Busler, E. Prout, A. C. Arensky). A new stage in the study of the structure of music. speech is associated with the name X. Riemann, who put the questions of its dismemberment in close connection with the system of muses. rhythms and metrics. In his works F. for the first time treated as a metric. unity (a group of two one-bar motifs with one heavy beat). Despite the historical progressiveness, the doctrine of dismemberment acquired in the works of Riemann several. scholastic a character not free from one-sidedness and dogmatism. From Rus. scientists on the structure of music. speech was paid attention to S. AND. Taneev, G. L. Cathar, I. AT. Sopoyn, L. A. Mazel, Yu. N. Tyulin, W. A. Zuckerman. In their works, as in modern hem. musicology, there has been a departure from the narrow, purely metrical understanding of F. and a broader view of this concept, based on a real-life dismemberment. Even Taneev and Katuar pointed out that F. may represent an internally indivisible construction and have a non-square structure (for example, a three-cycle). As shown in the works of Tyulin, F. can follow one after another, without uniting in higher order formations, which is characteristic of wok. music, as well as development sections in instr. music. T. o., in contrast to the periods and sentences characteristic of the exposition, F. turn out to be more “ubiquitous”, penetrating all the muses. prod. Mazel and Zuckerman spoke in favor of understanding F. as thematic-syntax. unity; like Tyulin, they emphasized the inevitability of cases when the length of the designation of a given muses. segment, you can use both the term “motive” and the term “F.”. Such cases arise when continuous constructions with a length of more than one measure are the first stage of articulation within a sentence. The differences lie in the point of view from which this phenomenon is considered: the term “motive” speaks rather of music. turnover in the meaning of the original unit of the subsequent thematic.

L. Beethoven. Sonata for piano, op. 106, part I.

References: Arensky A., Guide to the study of the forms of instrumental and vocal music, M., 1893, 1921; Catuar G., Musical form, part 1, M., 1934; Sposobin I., Musical form, M. – L., 1947, M., 1972; Mazel L., Structure of musical works, M., 1960, 1979; Tyulin Yu., The structure of musical speech, L., 1962; Mazel L., Zukkerman V., Analysis of musical works, M., 1967; Nazaikinsky K., On the psychology of musical perception, M., 1972.

I. V. Lavrentieva