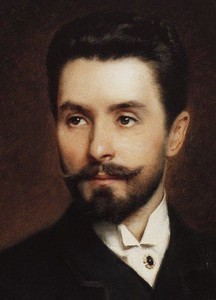

Nikolai Nikolaevich Figner (Nicolai Figner) |

Nicolai Figner

Russian singer, entrepreneur, vocal teacher. The husband of the singer M. I. Figner. The art of this singer played an important role in the development of the entire national opera theater, in the formation of the type of singer-actor who became a remarkable figure in the Russian opera school.

Once Sobinov, referring to Figner, wrote: “Under the spell of your talent, even cold, callous hearts trembled. Those moments of high uplift and beauty will not be forgotten by anyone who has ever heard you.”

And here is the opinion of the remarkable musician A. Pazovsky: “Having a characteristic tenor voice that is by no means remarkable for the beauty of the timbre, Figner nevertheless knew how to excite, sometimes even shock, with his singing the most diverse audience, including the most demanding in matters of vocal and stage art.”

Nikolai Nikolayevich Figner was born in the city of Mamadysh, Kazan province, on February 21, 1857. At first he studied at the Kazan gymnasium. But, not allowing him to finish the course there, his parents sent him to the St. Petersburg Naval Cadet Corps, where he entered on September 11, 1874. From there, four years later, Nikolai was released as a midshipman.

Enrolled in the naval crew, Figner was assigned to sail on the Askold corvette, on which he circumnavigated the world. In 1879, Nikolai was promoted to midshipman, and on February 9, 1881, he was dismissed due to illness from service with the rank of lieutenant.

His maritime career came to an abrupt end under unusual circumstances. Nikolai fell in love with an Italian Bonn who served in the family of his acquaintances. Contrary to the rules of the military department, Figner decided to marry immediately without the permission of his superiors. Nikolai secretly took Louise away and married her.

A new stage, decisively unprepared by the previous life, began in Figner’s biography. He decides to become a singer. He goes to the St. Petersburg Conservatory. At the conservatory test, the famous baritone and singing teacher I.P. Pryanishnikov takes Figner to his class.

However, first Pryanishnikov, then the famous teacher K. Everardi made him understand that he did not have vocal abilities, and advised him to abandon this idea. Figner obviously had a different opinion about his talent.

In the short weeks of study, Figner comes to a certain conclusion, however. “I need time, will and work!” he says to himself. Taking advantage of the material support offered to him, he, together with Louise, who was already expecting a child, leaves for Italy. In Milan, Figner hoped to find recognition from renowned vocal teachers.

“Having reached the Christopher Gallery in Milan, this singing exchange, Figner falls into the clutches of some charlatan from the “singing professors”, and he quickly leaves him not only without money, but also without a voice, Levick writes. – Some supernumerary choirmaster – the Greek Deroxas – finds out about his sad situation and extends a helping hand to him. He takes him on full dependency and prepares him for the stage at six months. In 1882 N.N. Figner will make his debut in Naples.

Starting a career in the West, N.N. Figner, as a perspicacious and intelligent person, carefully looks at everything. He is still young, but already mature enough to understand that in the path of one sweet-voiced singing, even in Italy, he may have many more thorns than roses. The logic of creative thinking, the realism of performance – these are the milestones that he focuses on. First of all, he begins to develop in himself a sense of artistic proportion and determine the boundaries of what is called good taste.

Figner notes that, for the most part, Italian opera singers almost do not own recitative, and if they do, they do not attach due importance to it. They expect arias or phrases with a high note, with an ending suitable for filleting or all sorts of sound fading, with an effective vocal position or a cascade of seductive sounds in tessitura, but they are clearly switched off from the action when their partners sing. They are indifferent to ensembles, that is, to places that essentially express the culmination of a particular scene, and they almost always sing them in a full voice, mainly so that they can be heard. Figner realized in time that these features by no means testify to the merits of the singer, that they are often harmful to the overall artistic impression and often run counter to the composer’s intentions. Before his eyes are the best Russian singers of his time, and the beautiful images of Susanin, Ruslan, Holofernes created by them.

And the first thing that distinguishes Figner from his initial steps is the presentation of recitatives, unusual for that time on the Italian stage. Not a single word without maximum attention to the musical line, not a single note out of touch with the word… The second feature of Figner’s singing is the correct calculation of light and shadow, juicy tone and subdued semitone, the brightest contrasts.

As if anticipating Chaliapin’s ingenious sound “economy”, Figner was able to keep his listeners under the spell of a finely pronounced word. A minimum of overall sonority, a minimum of each sound separately – exactly as much as is necessary for the singer to be equally well heard in all corners of the hall and for the listener to reach timbre colors.

Less than six months later, Figner made his successful debut in Naples in Gounod’s Philemon and Baucis, and a few days later in Faust. He was immediately noticed. They got interested. Tours began in different cities of Italy. Here is just one of the enthusiastic responses of the Italian press. The newspaper Rivista (Ferrara) wrote in 1883: “The tenor Figner, although he does not have a voice of great range, attracts with the richness of phrasing, impeccable intonation, grace of execution and, most of all, the beauty of high notes, which sound clean and energetic with him, without the slightest efforts. In the aria “Hail to you, sacred shelter”, in a passage in which he is excellent, the artist gives a chest “do” so clear and sonorous that it causes the most stormy applause. There were good moments in the challenge trio, in the love duet and in the final trio. However, since his means, although not unlimited, still provide him with this opportunity, it is desirable that other moments be saturated with the same feeling and the same enthusiasm, in particular the prologue, which required a more passionate and convincing interpretation. The singer is still young. But thanks to the intelligence and excellent qualities with which he is generously endowed, he will be able – provided a carefully selected repertoire – to advance far on his path.

After touring Italy, Figner performs in Spain and tours South America. His name quickly became widely known. After South America, performances in England follow. So Figner for five years (1882-1887) becomes one of the notable figures in the European opera house of that time.

In 1887, he was already invited to the Mariinsky Theater, and on unprecedented favorable terms. Then the highest salary of an artist of the Mariinsky Theater was 12 thousand rubles a year. The contract concluded with the Figner couple from the very beginning provided for payment of 500 rubles per performance with a minimum rate of 80 performances per season, that is, it amounted to 40 thousand rubles a year!

By that time, Louise had been abandoned by Figner in Italy, and his daughter had also remained there. On tour, he met a young Italian singer, Medea May. With her, Figner returned to St. Petersburg. Soon Medea became his wife. The married couple formed a truly perfect vocal duet that adorned the capital’s opera stage for many years.

In April 1887, he first appeared on the stage of the Mariinsky Theater as Radamès, and from that moment until 1904 he remained the leading soloist of the troupe, its support and pride.

Probably, in order to perpetuate the name of this singer, it would be enough that he was the first performer of Herman’s parts in The Queen of Spades. So the famous lawyer A.F. Koni wrote: “N.N. Figner did amazing things as Herman. He understood and presented Herman as a whole clinical picture of a mental disorder … When I saw N.N. Figner, I was amazed. I was amazed at the extent to which he accurately and deeply depicted madness … and how it developed in him. If I were a professional psychiatrist, I would say to the audience: “Go see N.N. Figner. He will show you a picture of the development of madness, which you will never meet and never find!.. Like N.N. Figner played it all! When we looked at the presence of Nikolai Nikolayevich, at the gaze fixed on one point and at complete indifference to others, it became scary for him … Whoever saw N.N. Figner in the role of Herman, he could follow the stages of madness on his game. This is where his great work comes into play. I did not know Nikolai Nikolayevich at that time, but later I had the honor of meeting him. I asked him: “Tell me, Nikolai Nikolayevich, where did you study madness? Did you read the books or did you see them?’ — ‘No, I didn’t read or study them, it just seems to me that it should be so.’ This is intuition…”

Of course, not only in the role of Herman showed his remarkable acting talent. Just as breathtakingly truthful was his Canio in Pagliacci. And in this role, the singer skillfully conveyed a whole gamut of feelings, achieving in a short period of one act of a huge dramatic increase, culminating in a tragic denouement. The artist left the strongest impression in the role of Jose (Carmen), where everything in his game was thought out, internally justified and at the same time lit up with passion.

Music critic V. Kolomiytsev wrote at the end of 1907, when Figner had already completed his performances:

“During his twenty-year stay in St. Petersburg, he sang a lot of parts. Success did not change him anywhere, but that particular repertoire of “cloak and sword”, which I spoke about above, was especially suited to his artistic personality. He was the hero of strong and spectacular, albeit operatic, conditional passions. Typically Russian and German operas in most cases were less successful for him. In general, to be fair and impartial, it should be said that Figner did not create various stage types (in the sense that, for example, Chaliapin creates them): almost always and in everything he remained himself, that is, all the same elegant, nervous and passionate first tenor. Even his make-up hardly changed – only the costumes changed, the colors thickened or weakened accordingly, certain details were shaded. But, I repeat, the personal, very bright qualities of this artist were very suitable for the best parts of his repertoire; moreover, it should not be forgotten that these specifically tenor parts themselves are, in their essence, very homogeneous.

If I’m not mistaken, Figner never appeared in Glinka’s operas. He did not sing Wagner either, except for an unsuccessful attempt to portray Lohengrin. In Russian operas, he was undoubtedly magnificent in the image of Dubrovsky in the opera Napravnik and especially Herman in Tchaikovsky’s The Queen of Spades. And then it was the incomparable Alfred, Faust (in Mephistopheles), Radames, Jose, Fra Diavolo.

But where Figner left a truly indelible impression was in the roles of Raoul in Meyerbeer’s Huguenots and Othello in Verdi’s opera. In these two operas, he many times gave us enormous, rare pleasure.

Figner left the stage at the height of his talent. Most listeners believed that the reason for this was the divorce from his wife in 1904. Moreover, Medea was to blame for the breakup. Figner found it impossible to perform with her on the same stage …

In 1907, the farewell benefit performance of Figner, who was leaving the opera stage, took place. “Russian Musical Newspaper” wrote in this regard: “His star rose somehow suddenly and immediately blinded both the public and the management, and, moreover, high society, whose goodwill raised Figner’s artistic prestige to a height hitherto unknown Russian opera singers… Figner stunned. He came to us, if not with an outstanding voice, then with an amazing manner of adapting the part to his vocal means and even more amazing vocal and dramatic playing.

But even after ending his career as a singer, Figner remained in the Russian opera. He became the organizer and leader of several troupes in Odessa, Tiflis, Nizhny Novgorod, led an active and versatile public activity, performed in public concerts, and was the organizer of a competition for creating opera works. The most noticeable mark in the cultural life was left by his activity as the head of the opera troupe of the St. Petersburg People’s House, where Figner’s outstanding directing abilities also manifested themselves.

Nikolai Nikolaevich Figner passed away on December 13, 1918.