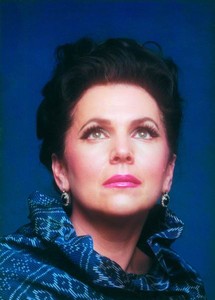

Nadezhda Zabela-Vrubel |

Nadezhda Zabela-Vrubel

Nadezhda Ivanovna Zabela-Vrubel was born on April 1, 1868 in a family of an old Ukrainian family. Her father, Ivan Petrovich, a civil servant, was interested in painting, music and contributed to the versatile education of his daughters – Catherine and Nadezhda. From the age of ten, Nadezhda studied at the Kiev Institute for Noble Maidens, from which she graduated in 1883 with a large silver medal.

From 1885 to 1891, Nadezhda studied at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, in the class of Professor N.A. Iretskaya. “Art needs a head,” said Natalia Alexandrovna. To resolve the issue of admission, she always listened to the candidates at home, got to know them in more detail.

Here is what L.G. writes. Barsova: “The whole palette of colors was built on impeccable vocals: a pure tone, as it were, endlessly and continuously flows and develops. The formation of the tone did not hinder the articulation of the mouth: “The consonants sing, they don’t lock, they sing!” Iretskaya prompted. She considered false intonation as the biggest fault, and forced singing was considered as the greatest disaster – a consequence of unfavorable breathing. The following requirements of Iretskaya were quite modern: “You must be able to hold your breath while you sing a phrase – breathe in easily, hold your diaphragm while you sing a phrase, feel the state of singing.” Zabela learned the lessons of Iretskaya perfectly … “

Already participation in the student performance “Fidelio” by Beethoven on February 9, 1891 drew the attention of specialists to the young singer who performed the part of Leonora. The reviewers noted “good school and musical understanding”, “strong and well-trained voice”, while pointing out the lack of “in the ability to stay on stage”.

After graduating from the conservatory, Nadezhda, at the invitation of A.G. Rubinstein makes a concert tour of Germany. Then she goes to Paris – to improve with M. Marchesi.

Zabela’s stage career began in 1893 in Kyiv, at the I.Ya. Setov. In Kyiv, she performs the roles of Nedda (Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci), Elizabeth (Wagner’s Tannhäuser), Mikaela (Bizet’s Carmen), Mignon (Thomas’ Mignon), Tatiana (Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin), Gorislava (Ruslan and Lyudmila” by Glinka), Crises (“Nero” by Rubinstein).

Of particular note is the role of Marguerite (Gounod’s Faust), one of the most complex and revealing in opera classics. Constantly working on the image of Margarita, Zabela interprets it more and more subtly. Here is one of the reviews from Kyiv: “Ms. Zabela, whom we met for the first time in this performance, created such a poetic stage image, she was so impeccably good in vocal terms, that from her first appearance on stage in the second act and from the first but the note of her opening recitative, sung impeccably, right up to the final scene in the dungeon of the last act, she completely captured the attention and disposition of the public.

After Kyiv, Zabela performed in Tiflis, where her repertoire included the roles of Gilda (Verdi’s Rigoletto), Violetta (Verdi’s La Traviata), Juliet (Gounod’s Romeo and Juliet), Inea (Meyerbeer’s African), Tamara ( The Demon” by Rubinstein), Maria (“Mazepa” by Tchaikovsky), Lisa (“The Queen of Spades” by Tchaikovsky).

In 1896, Zabela performed in St. Petersburg, at the Panaevsky Theater. At one of the rehearsals of Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel, Nadezhda Ivanovna met her future husband. Here is how she herself told about it: “I was amazed and even somewhat shocked that some gentleman ran up to me and, kissing my hand, exclaimed: “A charming voice!” T.S. Lyubatovich hurried to introduce me: “Our artist Mikhail Alexandrovich Vrubel” – and said to me aside: “A very expansive person, but quite decent.”

After the premiere of Hansel and Gretel, Zabela brought Vrubel to Ge’s house, where she then lived. Her sister “noted that Nadia was somehow especially youthful and interesting, and realized that this was due to the atmosphere of love that this particular Vrubel surrounded her.” Vrubel later said that “if she had refused him, he would have taken his own life.”

On July 28, 1896, the wedding of Zabela and Vrubel took place in Switzerland. The happy newlywed wrote to her sister: “In Mikh[ail Alexandrovich] I find new virtues every day; firstly, he is unusually meek and kind, simply touching, besides, I always have fun and surprisingly easy with him. I certainly believe in his competence regarding singing, he will be very useful to me, and it seems that I will be able to influence him.

As the most beloved, Zabela singled out the role of Tatiana in Eugene Onegin. She sang it for the first time in Kyiv, in Tiflis she chose this part for her benefit performance, and in Kharkov for her debut. M. Dulova, then a young singer, told about her first appearance on the stage of the Kharkov Opera Theater on September 18, 1896 in her memoirs: “Nadezhda Ivanovna made a pleasant impression on everyone: with her appearance, costume, demeanor … weight Tatyana – Zabela. Nadezhda Ivanovna was very pretty and stylish. The play “Onegin” was excellent.” Her talent flourished at the Mamontov Theatre, where she was invited by Savva Ivanovich in the autumn of 1897 with her husband. Soon there was her meeting with the music of Rimsky-Korsakov.

For the first time, Rimsky-Korsakov heard the singer on December 30, 1897 in the part of Volkhova in Sadko. “You can imagine how worried I was, speaking in front of the author in such a difficult game,” Zabela said. However, the fears turned out to be exaggerated. After the second picture, I met Nikolai Andreevich and received full approval from him.

The image of Volkhova corresponded to the personality of the artist. Ossovsky wrote: “When she sings, it seems like incorporeal visions sway and sweep before your eyes, meek and … almost elusive … When they have to experience grief, it’s not grief, but a deep sigh, without grumbling and hopes.”

Rimsky-Korsakov himself, after Sadko, writes to the artist: “Of course, you thereby composed the Sea Princess, that you created her image in singing and on stage, which will forever remain with you in my imagination …”

Soon Zabela-Vrubel began to be called “Korsakov’s singer”. She became the protagonist in the production of such masterpieces by Rimsky-Korsakov as The Pskovite Woman, May Night, The Snow Maiden, Mozart and Salieri, The Tsar’s Bride, Vera Sheloga, The Tale of Tsar Saltan, “Koschei the Deathless”.

Rimsky-Korsakov did not hide his relationship with the singer. Regarding The Maid of Pskov, he said: “In general, I consider Olga to be your best role, even if I was not even bribed by the presence of Chaliapin himself on the stage.” For the part of the Snow Maiden, Zabela-Vrubel also received the author’s highest praise: “I have never heard such a sung Snow Maiden as Nadezhda Ivanovna before.”

Rimsky-Korsakov immediately wrote some of his romances and operatic roles based on the artistic possibilities of Zabela-Vrubel. Here it is necessary to name Vera (“Boyarina Vera Sheloga”), and the Swan Princess (“The Tale of Tsar Saltan”), and the Princess Beloved Beauty (“Koschei the Immortal”), and, of course, Marfa, in “The Tsar’s Bride”.

On October 22, 1899, The Tsar’s Bride premiered. In this game, the best features of Zabela-Vrubel’s talent appeared. No wonder contemporaries called her the singer of the female soul, female quiet dreams, love and sadness. And at the same time, the crystal purity of sound engineering, the crystal transparency of the timbre, the special tenderness of the cantilena.

Critic I. Lipaev wrote: “Ms. Zabela turned out to be a beautiful Marfa, full of meek movements, dove-like humility, and in her voice, warm, expressive, not embarrassed by the height of the party, everything captivated with musicality and beauty … Zabela is incomparable in scenes with Dunyasha, with Lykov, where all she has is love and hope for a rosy future, and even more good in the last act, when the potion has already poisoned the poor thing and the news of Lykov’s execution drives her crazy. And in general, Marfa found a rare artist in the person of Zabela.

Feedback from another critic, Kashkin: “Zabela sings [Martha’s] aria surprisingly well. This number requires rather exceptional vocal means, and hardly many singers have such a lovely mezza voche in the highest register as Zabela flaunts. It is hard to imagine this aria sung better. The scene and aria of the crazy Martha was performed by Zabela in an unusually touching and poetic way, with a great sense of proportion. Engel also praised Zabela’s singing and playing: “Marfa [Zabela] was very good, how much warmth and touchingness was in her voice and in her stage performance! In general, the new role was almost entirely successful for the actress; she spends almost the entire part in some kind of mezza voche, even on high notes, which gives Marfa that halo of meekness, humility and resignation to fate, which, I think, was drawn in the poet’s imagination.

Zabela-Vrubel in the role of Martha made a great impression on O.L. Knipper, who wrote to Chekhov: “Yesterday I was at the opera, I listened to The Tsar’s Bride for the second time. What marvelous, subtle, graceful music! And how beautifully and simply Marfa Zabela sings and plays. I cried so well in the last act – she touched me. She surprisingly simply leads the scene of madness, her voice is clear, high, soft, not a single loud note, and cradles. The whole image of Martha is full of such tenderness, lyricism, purity – it just doesn’t get out of my head. ”

Of course, Zabela’s operatic repertoire was not limited to the music of the author of The Tsar’s Bride. She was an excellent Antonida in Ivan Susanin, she sang soulfully Iolanta in Tchaikovsky’s opera of the same name, she even succeeded in the image of Mimi in Puccini’s La Boheme. And yet, the Russian women of Rimsky-Korsakov evoked the greatest response in her soul. It is characteristic that his romances also formed the basis of Zabela-Vrubel’s chamber repertoire.

In the most sorrowful fate of the singer there was something from the heroines of Rimsky-Korsakov. In the summer of 1901, Nadezhda Ivanovna had a son, Savva. But two years later he fell ill and died. Added to this was the mental illness of her husband. Vrubel died in April 1910. And her creative career itself, at least theatrical, was unfairly short. After five years of brilliant performances on the stage of the Moscow Private Opera, from 1904 to 1911 Zabela-Vrubel served at the Mariinsky Theatre.

The Mariinsky Theater had a higher professional level, but it lacked the atmosphere of celebration and love that reigned in the Mamontov Theater. M.F. Gnesin wrote with chagrin: “When I once got to the theater at Sadko with her participation, I could not help but be upset by some of her invisibility in the performance. Her appearance, and her singing, were still charming for me, and yet, compared with the former, it was, as it were, a gentle and somewhat dull watercolor, only reminiscent of a picture painted with oil paints. In addition, her stage environment was devoid of poetry. The dryness inherent in productions in state theaters was felt in everything.

On the imperial stage, she never had a chance to perform the part of Fevronia in Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera The Tale of the Invisible City of Kitezh. And contemporaries claim that on the concert stage this part sounded great for her.

But the chamber evenings of Zabela-Vrubel continued to attract the attention of true connoisseurs. Her last concert took place in June 1913, and on July 4, 1913, Nadezhda Ivanovna died.