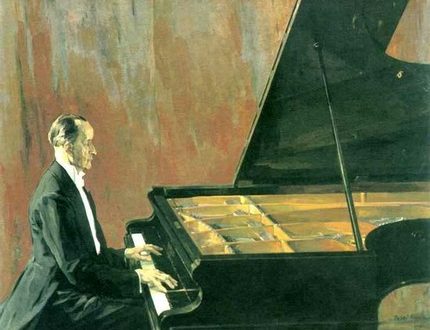

Mikhail Sergeevich Voskresensky |

Mikhail Voskresensky

Fame comes to an artist in different ways. Someone becomes famous almost unexpectedly for others (sometimes for himself). Glory flashes for him instantly and enchantingly bright; this is how Van Cliburn entered the history of piano performance. Others start slowly. Inconspicuous at first in the circle of colleagues, they win recognition gradually and gradually – but their names are usually pronounced with great respect. This way, as experience shows, is often more reliable and truer. It was to them that Mikhail Voskresensky went in art.

He was lucky: fate brought him together with Lev Nikolaevich Oborin. At Oborin in the early fifties – at the time when Voskresensky first crossed the threshold of his class – there were not so many really bright pianists among his students. Voskresensky managed to win the lead, he became one of the first-born among the laureates of international competitions prepared by his professor. Moreover. Restrained, at times, perhaps a little aloof in his relations with student youth, Oborin made an exception for Voskresensky – singled him out among the rest of his students, made him his assistant at the conservatory. For a number of years, the young musician worked side by side with the renowned master. He, like no one else, was exposed to the hidden secrets of Oborinsky performing and pedagogical art. Communication with Oborin gave Voskresensky exceptionally much, determined some of the fundamentally important facets of his artistic appearance. But more on that later.

Mikhail Sergeevich Voskresensky was born in the city of Berdyansk (Zaporozhye region). He lost his father early, who died during the Great Patriotic War. He was raised by his mother; she was a music teacher and taught her son an initial piano course. The first years after the end of the war Voskresensky spent in Sevastopol. He studied in high school, continued to play the piano under the supervision of his mother. And then the boy was transferred to Moscow.

He was admitted to the Ippolitov-Ivanov Musical College and sent to the class of Ilya Rubinovich Klyachko. “I can only say the kindest words about this excellent person and specialist,” Voskresensky shares his memories of the past. “I came to him as a very young man; I said goodbye to him four years later as an adult musician, having learned a lot, having learned a lot … Klyachko put an end to my childishly naive ideas about piano playing. He set me serious artistic and performing tasks, introduced real musical imagery into the world … “

At the school, Voskresensky quickly showed his remarkable natural abilities. He often and successfully played at open parties and concerts. He enthusiastically worked on technique: he learned, for example, all fifty studies (op. 740) by Czerny; this significantly strengthened his position in pianism. (“Cherny brought me exceptionally great benefit as a performer. I would not recommend any young pianist to bypass this author during their studies.”) In a word, it was not difficult for him to enter the Moscow Conservatory. He was enrolled as a first year student in 1953. For some time, Ya. I. Milshtein was his teacher, but soon, however, he moved to Oborin.

It was a hot, intense time in the biography of the country’s oldest musical institution. The time for performing competitions began… Voskresensky, as one of the leading and most “strong” pianists of the Oborinsky class, fully paid tribute to the general enthusiasm. In 1956 he went to the International Schumann Competition in Berlin and returned from there with the third prize. A year later, he has a “bronze” at the piano competition in Rio de Janeiro. 1958 – Bucharest, Enescu competition, second prize. Finally, in 1962, he completed his competitive “marathon” at the Van Cliburn competition in the USA (third place).

“Probably, there were really too many competitions on my life path. But not always, you see, everything here depended on me. Sometimes the circumstances were such that it was not possible to refuse to participate in the competition … And then, I must admit, the competitions carried away, captured – youth is youth. They gave a lot in a purely professional sense, contributed to pianistic progress, brought a lot of vivid impressions: joys and sorrows, hopes and disappointments … Yes, yes, and disappointments, because at competitions – now I am well aware of this – the role of fortune, happiness, chance is too great … “

From the beginning of the sixties, Voskresensky became more and more famous in Moscow musical circles. He successfully gives concerts (GDR, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Romania, Japan, Iceland, Poland, Brazil); shows a passion for teaching. Oborin’s assistantship ends with the fact that he is entrusted with his own class (1963). The young musician is being spoken louder and louder as one of the direct and consistent adherents of Oborin’s line in pianism.

And with good reason. Like his teacher, Voskresensky from an early age was characterized by a calm, clear and intelligent look at the music he performed. Such, on the one hand, is his nature, on the other hand, the result of many years of creative communication with the professor. There is nothing excessive or disproportionate in Voskresensky’s playing, in his interpretive concepts. Excellent order in everything that is done at the keyboard; everywhere and everywhere – in sound gradations, tempos, technical details – strictly strict control. In his interpretations, there is almost no controversial, internally contradictory; what is even more important for characterizing his style is nothing overly personal. Listening to pianists like him, one sometimes comes to mind the words of Wagner, who said that music performed clearly, with true artistic meaning and at a high professional level – “correctly”, in the words of the great composer – brings to the “pro-sacred feeling” unconditional satisfaction (Wagner R. About conducting// Conducting performance. — M., 1975. P. 124.). And Bruno Walter, as you know, went even further, believing that the accuracy of performance “radiates radiance.” Voskresensky, we repeat, is an accurate pianist …

And one more feature of his performing interpretations: in them, as once with Oborin, there is not the slightest emotional excitement, not a shadow of affectation. Nothing from immoderation in the manifestation of feelings. Everywhere – from musical classics to expressionism, from Handel to Honegger – spiritual harmony, elegant balance of inner life. Art, as philosophers used to say, is more of an “Apollonian” rather than a “Dionysian” warehouse …

Describing the game of Voskresensky, one cannot remain silent about one long-standing and well-visible tradition in the musical and performing arts. (In foreign pianism, it is usually associated with the names of E. Petri and R. Casadesus, in Soviet pianism, again with the name of L. N. Oborin.) This tradition puts the performance process at the forefront structural idea works. For artists who adhere to it, making music is not a spontaneous emotional process, but a consistent disclosure of the artistic logic of the material. Not a spontaneous expression of will, but a beautifully and carefully carried out “construction”. They, these artists, are invariably attentive to the aesthetic qualities of the musical form: to the harmony of the sound structure, the ratio of the whole and the particulars, the alignment of proportions. It is no coincidence that I. R. Klyachko, who is better than anyone else familiar with the creative method of his former student, wrote in one of the reviews that Voskresensky manages to achieve “the most difficult thing – the expressiveness of the form as a whole”; similar opinions can often be heard from other specialists. In responses to Voskresensky’s concertos, it is usually emphasized that the pianist’s performing actions are well thought out, substantiated, and calculated. Sometimes, however, critics believe, all this somewhat muffles the liveliness of his poetic feeling: “With all these positive aspects,” L. Zhivov noted, “sometimes one feels excessive emotional restraint in the pianist’s playing; it is possible that the desire for accuracy, special sophistication of each detail sometimes goes to the detriment of improvisation, immediacy of performance ” (Zhivov L. All Chopin nocturnes//Musical life. 1970. No. 9. S.). Well, maybe the critic is right, and Voskresensky really does not always, not at every concert captivate and ignite. But almost always convincing (At one time, B. Asafiev wrote in the wake of the performances in the USSR of the outstanding German conductor Hermann Abendroth: “Abendroth knows how to convince, not always being able to captivate, elevate and bewitch” (B. Asafiev. Critical articles, essays and reviews. – M .; L., 1967. S. 268). L. N. Oborin always convinced the audience of the forties and fifties in a similar way; such is essentially the effect on the public of his disciple.

He is usually referred to as a musician with an excellent school. Here he is really the son of his time, generation, environment. And without exaggeration, one of the best … On the stage, he is invariably correct: many could envy such a happy combination of school, psychological stability, self-control. Oborin once wrote: “In general, I believe that, first of all, it would not hurt for every performer to have a dozen or two rules of“ good behavior in music ”. These rules should relate to the content and form of performance, aesthetics of sound, pedalization, etc.” (Oborin L. On some principles of piano technique Questions of piano performance. – M., 1968. Issue 2. P. 71.). It is not surprising that Voskresensky, one of the creative adherents of Oborin and those closest to him, firmly mastered these rules during his studies; they became second nature to him. Whatever author he puts in his programs, in his game one can always feel the limits outlined by impeccable upbringing, stage etiquette, and excellent taste. Previously, it happened, no, no, yes, and he went beyond these limits; one can recall, for example, his interpretations of the sixties – Schumann’s Kreisleriana and Vienna Carnival, and some other works. (There is Voskresensky’s gramophone record, vividly reminiscent of these interpretations.) In a fit of youthful ardor, he at times allowed himself to sin in some way against what is meant by performing “comme il faut”. But that was only before, now, never.

In the XNUMXs and XNUMXs, Voskresensky performed a number of compositions – the B-flat major sonata, musical moments and Schubert’s “Wanderer” fantasy, Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto, Schnittke’s Concerto, and much more. And I must say that each of the pianist’s programs brought a lot of truly pleasant minutes to the public: meetings with intelligent, impeccably educated people are always pleasing – the concert hall is no exception in this case.

At the same time, it would be wrong to believe that Voskresensky’s performing merits only fit under some voluminous set of excellent rules – and only … His taste and musical sense are from nature. In his youth, he could have had the most worthy mentors – and yet what constitutes the main and most intimate in the activity of an artist, they would not have taught either. “If we taught taste and talent with the help of rules,” said the famous painter D. Reynolds, “then there would be no more taste or talent” (About music and musicians. – L., 1969. S. 148.).

As an interpreter, Voskresensky likes to take on a wide variety of music. In oral and printed speeches, he spoke more than once, and with all conviction, for the widest possible repertoire of a touring artist. “A pianist,” he declared in one of his articles, “unlike a composer, whose sympathies depend on the direction of his talent, must be able to play the music of different authors. He cannot limit his tastes to any particular style. A modern pianist must be versatile” (Voskresensky M. Oborin – artist and teacher / / L. N. Oborin. Articles. Memoirs. – M., 1977. P. 154.). It is really not easy for Voskresensky himself to isolate what would be preferable for him as a concert player. In the mid-seventies, he played all of Beethoven’s sonatas in a cycle of several clavirabends. Does this mean that his role is a classic? Hardly. For he, at another time, played all the nocturnes, polonaises and a number of other works by Chopin on records. But again, that doesn’t say much. On the posters of his concerts are preludes and fugues by Shostakovich, Prokofiev’s sonatas, Khachaturian’s concerto, works by Bartok, Hindemith, Milhaud, Berg, Rossellini, piano novelties by Shchedrin, Eshpai, Denisov … It is significant, however, not that he performs a lot. Symptomatically different. In a variety of stylistic regions, he feels equally calm and confident. This is the whole of Voskresensky: in the ability to maintain creative balance everywhere, to avoid unevenness, extremes, a tilt in one direction or another.

Artists like him are usually good at revealing the stylistic nature of the music they perform, conveying the “spirit” and “letter”. This is undoubtedly a sign of their high professional culture. However, there may be one drawback here. It has already been said earlier that Voskresensky’s play sometimes lacks specificity, a sharply defined individual-personal intonation. Indeed, his Chopin is the very euphony, harmony of lines, performing “bon tone”. Beethoven in him is both an imperative tone, and strong-willed aspiration, and a solid, integrally built architectonics, which are necessary in the works of this author. Schubert in his transmission demonstrates a number of traits and features inherent in Schubert; his Brahms is almost “one hundred percent” Brahms, Liszt is Liszt, etc. Sometimes one would still like to feel in the works that belong to him, his own creative “genes”. Stanislavsky called works of theatrical art “living beings”, ideally inheriting the generic characteristics of both of their “parents”: these works, he said, should represent the “spirit from the spirit and flesh from the flesh” of the playwright and artist. Probably, the same should be in principle in musical performance …

However, there is no master to whom it would be impossible to address with his eternal “I would like to.” Resurrection is no exception.

The properties of Voskresensky’s nature, listed above, make him a born teacher. He gives his wards almost everything that can be offered to students in art – broad knowledge and professional culture; initiates them into the secrets of craftsmanship; instills the traditions of the school in which he himself was brought up. E. I. Kuznetsova, a student of Voskresensky and laureate of the piano competition in Belgrade, says: “Mikhail Sergeevich knows how to make the student understand almost immediately during the lesson what tasks he faces and what needs to be further worked on. This shows the great pedagogical talent of Mikhail Sergeevich. I have always been amazed at how quickly he can get to the heart of a student’s predicament. And not only to penetrate, of course: being an excellent pianist, Mikhail Sergeevich always knows how to suggest how and where to find a practical way out of the difficulties that arise.

His characteristic feature is, – continues E. I. Kuznetsova, – that he is a truly thinking musician. Thinking broadly and unconventionally. For example, he was always occupied with the problems of the “technology” of piano playing. He thought a lot, and does not stop thinking about sound production, pedaling, landing at the instrument, hand positioning, techniques, etc. He generously shares his observations and thoughts with young people. Meetings with him activate the musical intellect, develop and enrich it…

But perhaps most importantly, he infects the class with his creative enthusiasm. Instills a love for real, high art. He instills in his students professional honesty and conscientiousness, which are to a large extent characteristic of himself. He can, for example, come to the conservatory immediately after an exhausting tour, almost straight from the train, and, immediately starting classes, work selflessly, with full dedication, sparing neither himself nor the student, not noticing the fatigue, the time spent … Somehow he threw such a phrase (I remember it well): “The more energy you spend in creative affairs, the faster and more fully it is restored.” He is all in these words.

In addition to Kuznetsova, Voskresensky’s class included well-known young musicians, participants in international competitions: E. Krushevsky, M. Rubatskite, N. Trull, T. Siprashvili, L. Berlinskaya; Stanislav Igolinsky, laureate of the Fifth Tchaikovsky Competition, also studied here – the pride of Voskresensky as a teacher, an artist of truly outstanding talent and well-deserved popularity. Other pupils of Voskresensky, without gaining loud fame, nevertheless lead an interesting and creatively full-blooded life in the art of music – they teach, play in ensembles, and are engaged in accompanist work. Voskresensky once said that a teacher should be judged by what his students represent to, after completion of the course of study – in an independent field. The fates of most of his pupils speak of him as a teacher of a truly high class.

“I love visiting the cities of Siberia,” Voskresensky once said. – Why there? Because the Siberians, it seems to me, have retained a very pure and direct attitude to music. There is no that satiety, that listener snobbery that you sometimes feel in our metropolitan auditoriums. And for a performer to see the enthusiasm of the public, its sincere craving for art is the most important thing.

Voskresensky really often visits the cultural centers of Siberia, large and not too large; he is well known and appreciated here. “Like every touring artist, I have concert “points” that are especially close to me – cities where I always feel good contacts with the audience.

And do you know what else I have fallen in love with lately, that is, I loved before, and even more so now? Perform in front of children. As a rule, at such meetings there is a particularly lively and warm atmosphere. I never deny myself this pleasure.

… In 1986-1988, Voskresensky traveled to France for the summer months, to Tours, where he participated in the work of the International Academy of Music. During the day he gave open lessons, in the evenings he performed in concerts. And, as is often the case with our performers, he brought home excellent press – a whole bunch of reviews (“Five measures were enough to understand that something unusual was happening on the stage,” wrote the newspaper Le Nouvelle Republique in July 1988, following Voskresensky’s performance in Tours, where he played Chopin Scriabin and Mussorgsky. “Pages heard by at least a hundred times were transformed by the power of the talent of this amazing artistic personality.”). “Abroad, they respond quickly and promptly in the newspapers to the events of musical life. It remains only to regret that we, as a rule, do not have this. We often complain about the poor attendance at philharmonic concerts. But this often happens due to the fact that the public, and the employees of the philharmonic society, are simply not aware of what is interesting today in our performing arts. People lack the necessary information, they feed on rumors – sometimes true, sometimes not. Therefore, it turns out that some talented performers – especially young people – do not fall into the field of view of the mass audience. And they feel bad, and real music lovers. But especially for the young artists themselves. Not having the required number of public concert performances, they are disqualified, lose their form.

I have, in short, – and do I really have one? – very serious claims to our musical and performing press.

In 1985, Voskresensky turned 50 years old. Do you feel this milestone? I asked him. “No,” he replied. Honestly, I do not feel my age, although the numbers seem to be growing steadily. I’m an optimist, you see. And I am convinced that pianism, if you approach it by and large, is a matter of second half of a person’s life. You can progress for a very long time, almost all the time that you are engaged in your profession. You never know specific examples, specific creative biographies confirming this.

The problem is not age per se. She is in another. In our constant employment, workload and congestion with various things. And if something sometimes does not come out on stage as we would like, it is mainly for this reason. However, I am not alone here. Almost all of my conservatory colleagues are in a similar position. The bottom line is that we still feel that we are primarily performers, but pedagogy has taken too much and an important place in our lives to ignore it, not to devote a huge amount of time and effort to it.

Perhaps I, like the other professors who work alongside me, have more students than is necessary. The reasons for this are different. Often I myself cannot refuse a young man who has entered the conservatory, and I take him to my class, because I believe that he has a bright, strong talent, from which something very interesting can develop in the future.

… In the mid-eighties, Voskresensky played a lot of Chopin’s music. Continuing the work begun earlier, he performed all the works for piano written by Chopin. I also remember from the performances of this time several monograph concerts dedicated to other romantics – Schumann, Brahms, Liszt. And then he was drawn to Russian music. He learned Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, which he had never performed before; recorded 7 sonatas by Scriabin on the radio. Those who have closely looked at the pianist’s works mentioned above (and some others relating to the last period of time) could not fail to notice that Voskresensky began to play somehow on a larger scale; that his artistic “statements” have become more embossed, mature, weighty. “Pianism is the work of the second half of life,” he says. Well, in a certain sense this can be true – if the artist does not stop intensive inner work, if some underlying shifts, processes, metamorphoses continue to occur in his spiritual world.

“There is another side of the activity that has always attracted me, and now it has become especially close,” says Voskresensky. — I mean playing the organ. Once I studied with our outstanding organist L. I. Roizman. He did this, as they say, for himself, to expand the general musical horizons. The classes lasted about three years, but during this generally short period I took from my mentor, it seems to me, quite a lot – for which I am still sincerely grateful to him. I won’t claim that my repertoire as an organist is that wide. However, I’m not going to actively replenish it; Still, my direct specialty is elsewhere. I give several organ concerts a year and get real joy from it. I don’t need more than that.”

… Voskresensky managed to achieve a lot both on the concert stage and in pedagogy. And rightfully so everywhere. There was nothing accidental in his career. Everything was achieved by labor, talent, perseverance, will. The more strength he gave to the cause, the stronger he eventually became; the more he spent himself, the faster he recovered – in his example, this pattern is manifested with all obviousness. And he is doing exactly the right thing, which reminds the youth of her.

G. Tsypin, 1990