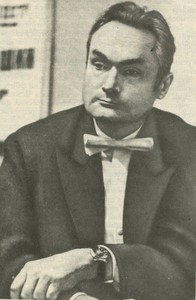

Lev Nikolaevich Vlasenko |

Lev Vlasenko

There are cities with special merits before the musical world, for example, Odessa. How many brilliant names donated to the concert stage in the pre-war years. Tbilisi, the birthplace of Rudolf Kerer, Dmitry Bashkirov, Eliso Virsalazze, Liana Isakadze and a number of other prominent musicians, has something to be proud of. Lev Nikolaevich Vlasenko also began his artistic path in the capital of Georgia – a city of long and rich artistic traditions.

As is often the case with future musicians, his first teacher was his mother, who once taught herself at the piano department of the Tbilisi Conservatory. After some time, Vlasenko goes to the famous Georgian teacher Anastasia Davidovna Virsaladze, graduates, studying in her class, a ten-year music school, then the first year of the conservatory. And, following the path of many talents, he moves to Moscow. Since 1948, he has been among the students of Yakov Vladimirovich Flier.

These years are not easy for him. He is a student of two higher educational institutions at once: in addition to the conservatory, Vlasenko studies (and successfully completes his studies in due time) at the Institute of Foreign Languages; The pianist is fluent in English, French, Italian. And yet the young man has enough energy and strength for everything. At the conservatory, he increasingly performs at student parties, his name becomes known in musical circles. However, more is expected of him. Indeed, in 1956 Vlasenko won the first prize at the Liszt Competition in Budapest.

Two years later, he again participates in the competition of performing musicians. This time, at his home in Moscow, at the First International Tchaikovsky Competition, the pianist won the second prize, leaving behind only Van Cliburn, who was then in the prime of his enormous talent.

Vlasenko says: “Shortly after graduating from the conservatory, I was drafted into the ranks of the Soviet Army. For about a year I did not touch the instrument – I lived with completely different thoughts, deeds, worries. And, of course, pretty nostalgic for music. When I was demobilized, I set to work with tripled energy. Apparently, in my acting there was then some kind of emotional freshness, unspent artistic strength, a thirst for stage creativity. It always helps on the stage: it helped me at that time too.

The pianist says that he used to be asked the question: on which of the tests – in Budapest or Moscow – did he have a harder time? “Of course, in Moscow,” he answered in such cases, “The Tchaikovsky Competition, at which I performed, was held for the first time in our country. Впервые – that says it all. He aroused great interest – he brought together the most prominent musicians, both Soviet and foreign, in the jury, attracted the widest audience, got into the center of attention of radio, television, and the press. It was extremely difficult and responsible to play at this competition – each entry to the piano was worth a lot of nervous tension … “

Victories at reputable musical competitions – and the “gold” won by Vlasenko in Budapest, and his “silver” won in Moscow were regarded as major victories – opened the doors to the big stage for him. He becomes a professional concert performer. His performances both at home and in other countries attract numerous listeners. He, however, is not just given signs of attention as a musician, the owner of valuable laureate regalia. Attitude towards him from the very beginning is determined differently.

There are on the stage, as in life, natures that enjoy universal sympathy – direct, open, sincere. Vlasenko as an artist among them. You always believe him: if he is passionate about interpreting a work, he is so truly passionate, excited – so excited; if not, he can’t hide it. The so-called art of performance is not his domain. He does not act and does not dissemble; his motto could be: “I say what I think, I express how I feel.” Hemingway has wonderful words with which he characterizes one of his heroes: “He was truly, humanly beautiful from the inside: his smile came from the very heart or from what is called the soul of a person, and then cheerfully and openly came to the surface , that is, illuminated the face ” (Hemingway E. Beyond the river, in the shade of trees. – M., 1961. S. 47.). Listening to Vlasenko in his best moments, it happens that you remember these words.

And one more thing impresses the public when meeting with a pianist – his stage sociability. Are there few of those who close themselves on the stage, withdraw into themselves from excitement? Others are coldish, restrained by nature, this makes itself felt in their art: they, according to a common expression, are not very “sociable”, they keep the listener as if at a distance from themselves. With Vlasenko, due to the peculiarities of his talent (whether artistic or human), it is easy, as if by itself, to establish contact with the audience. People listening to him for the first time sometimes express surprise – the impression is that they have long and well known him as an artist.

Those who closely knew Vlasenko’s teacher, Professor Yakov Vladimirovich Flier, argue that they had much in common – a bright pop temperament, generosity of emotional outpourings, a bold, sweeping manner of playing. It really was. It is no coincidence that, having arrived in Moscow, Vlasenko became a student of Flier, and one of the closest students; later their relationship grew into friendship. However, the kinship of the creative natures of the two musicians was evident even from their repertoire.

Old-timers of concert halls remember well how Flier once shone in Liszt’s programs; there is a pattern in the fact that Vlasenko also made his debut with the works of Liszt (competition in 1956 in Budapest).

“I love this author,” says Lev Nikolaevich, “his proud artistic pose, noble pathos, spectacular toga of romance, oratory style of expression. It so happened that in the music of Liszt I always easily managed to find myself … I remember that from a young age I played it with particular pleasure.

Vlasenko, however, not only started from Liszt your way to the big concert stage. And today, many years later, the works of this composer are at the center of his programs – from etudes, rhapsodies, transcriptions, pieces from the cycle “Years of Wanderings” to sonatas and other works of large form. So, a notable event in the philharmonic life of Moscow in the 1986/1987 season was Vlasenko’s performance of both piano concertos, “Dance of Death” and “Fantasy on Hungarian Themes” by Liszt; accompanied by an orchestra conducted by M. Pletnev. (This evening was dedicated to the 175th anniversary of the composer’s birth.) The success with the public was really great. And no wonder. Sparkling piano bravura, general elation of tone, loud stage “speech”, fresco, powerful playing style – all this is Vlasenko’s true element. Here the pianist appears from the most advantageous side for himself.

There is another author who is no less close to Vlasenko, just as the same author was close to his teacher, Rachmaninov. On the posters of Vlasenko you can see piano concertos, preludes and other Rachmaninoff pieces. When a pianist is “on the beat”, he is really good at this repertoire: he floods the audience with a wide flood of feelings, “overwhelms”, as one of the critics put it, with sharp and strong passions. Masterfully owns Vlasenko and thick, “cello” timbres that play such a big role in Rachmaninov’s piano music. He has heavy and soft hands: sound painting with “oil” is closer to his nature than dryish sound “graphics”; – one could say, following the analogy begun with painting, that a wide brush is more convenient for him than a sharply sharpened pencil. But, probably, the main thing in Vlasenko, since we talk about his interpretations of Rachmaninov’s plays, is that he able to embrace the musical form as a whole. Hug freely and naturally, without being distracted, perhaps, by some little things; this is exactly how, by the way, Rachmaninov and Flier performed.

Finally, there is the composer, who, according to Vlasenko, has become almost the closest to him over the years. This is Beethoven. Indeed, Beethoven’s sonatas, primarily Pathetique, Lunar, Second, Seventeenth, Appassionata, Bagatelles, variation cycles, Fantasia (Op. 77), formed the basis of Vlasenko’s repertoire of the seventies and eighties. An interesting detail: not referring to himself as a specialist in lengthy conversations about music – to those who know how and love to interpret it in words, Vlasenko, nevertheless, spoke several times with stories about Beethoven on Central Television.

“With age, I find in this composer more and more attractive to me,” says the pianist. “For a long time I had one dream – to play a cycle of five of his piano concertos.” Lev Nikolaevich fulfilled this dream, and excellently, in one of the last seasons.

Of course, Vlasenko, as a professional guest performer should, turns to a wide variety of music. His performing arsenal includes Scarlatti, Mozart, Schubert, Brahms, Debussy, Tchaikovsky, Scriabin, Prokofiev, Shostakovich… However, his success in this repertoire, where something is closer to him, and something further, is not the same, not always stable and even. However, one should not be surprised: Vlasenko has a quite definite performing style, the basis of which is a large, sweeping virtuosity; he plays truly like a man – strong, clear and simple. Somewhere it convinces, and completely, somewhere not quite. It is no coincidence that if you take a closer look at Vlasenko’s programs, you will notice that he approaches Chopin with caution …

Talking about thо performed by the artist, it is impossible not to note the most successful in his programs of recent years. Here is Liszt’s B minor sonata and Rachmaninov’s etudes-paintings, Scriabin’s Third Sonata and Ginastera’s Sonata, Debussy’s Images and his Island of Joy, Hummel’s Rondo in E flat major and Albeniz’s Cordova… Since 1988, Vlasenko’s posters have been to see the Second Sonata of B. A. Arapov, recently learned by him, as well as Bagatelles, Op. 126 Beethoven, Preludes, Op. 11 and 12 Scriabin (also new works). In the interpretations of these and other works, perhaps, the features of Vlasenko’s modern style are especially clearly visible: the maturity and depth of artistic thought, combined with a lively and strong musical feeling that has not faded with time.

Since 1952, Lev Nikolaevich has been teaching. At first, at the Moscow Choir School, later at the Gnessin School. Since 1957 he has been among the teachers of the Moscow Conservatory; in his class, N. Suk, K. Oganyan, B. Petrov, T. Bikis, N. Vlasenko and other pianists received a ticket to stage life. M. Pletnev studied with Vlasenko for several years – in his last year at the conservatory and as an assistant trainee. Perhaps these were the brightest and most exciting pages of the pedagogical biography of Lev Nikolaevich …

Teaching means constantly answering some questions, solving numerous and unexpected problems that life, educational practice, and student youth pose. What, for example, should be taken into account when selecting an educational and pedagogical repertoire? How do you build relationships with students? how to conduct a lesson so that it is as effective as possible? But perhaps the greatest anxiety arises for any teacher of the conservatory in connection with the public performances of his pupils. And the young musicians themselves are persistently looking for an answer from the professors: what is needed for stage success? is it possible to somehow prepare, “provide” it? At the same time, obvious truths – such as the fact that, they say, the program must be sufficiently learned, technically “done”, and that “everything must work out and come out” – few people can be satisfied. Vlasenko knows that in such cases one can say something really useful and necessary only on the basis of one’s own experience. Only if you start from the experienced and experienced by him. Actually, this is exactly what those whom he teaches expect from him. “Art is the experience of personal life, told in images, in sensations,” A. N. Tolstoy wrote, “ personal experience that claims to be a generalization» (Tolstykh V. I. Art and Morality. – M., 1973. S. 265, 266.). The art of teaching, even more so. Therefore, Lev Nikolaevich willingly refers to his own performing practice – both in the classroom, among students, and in public conversations and interviews:

“Some unpredictable, inexplicable things are constantly happening on stage. For example, I can arrive at the concert hall well rested, prepared for the performance, confident in myself – and the clavierabend will pass without much enthusiasm. And vice versa. I can go on stage in such a state that it seems that I will not be able to extract a single note from the instrument – and the game will suddenly “go”. And everything will become easy, pleasant … What’s the matter here? Don’t know. And no one probably knows.

Although there is something to foresee in order to facilitate the first minutes of your stay on the stage – and they are the most difficult, restless, unreliable … – I think it is still possible. What matters, for example, is the very construction of the program, its layout. Every performer knows how important this is – and precisely in connection with the problem of pop well-being. In principle, I tend to start a concerto with a piece in which I feel as calm and confident as possible. When playing, I try to listen as closely as possible to the sound of the piano; adapt to the acoustics of the room. In short, I strive to fully enter, immerse myself in the performing process, become interested in what I do. This is the most important thing – to get interested, get carried away, fully concentrate on the game. Then the excitement begins to subside gradually. Or maybe you just stop noticing it. From here it is already a step to the creative state that is required.

Vlasenko attaches great importance to everything that one way or another precedes a public speech. “I remember once I was talking on this subject with the wonderful Hungarian pianist Annie Fischer. She has a special routine on the day of the concert. She eats almost nothing. One boiled egg without salt, and that’s it. This helps her to find the necessary psycho-physiological state on the stage – nervously upbeat, joyfully excited, maybe even a little exalted. That special subtlety and sharpness of feelings appears, which is absolutely necessary for a concert performer.

All this, by the way, is easily explained. If a person is full, it usually tends to fall into a complacently relaxed state, isn’t it? In itself, it may be both pleasant and “comfortable”, but it is not very suitable for performing in front of an audience. For only one who is internally electrified, who has all his spiritual strings vibrating tensely, can evoke a response from the audience, push it to empathy …

Therefore, sometimes the same thing happens, as I have already mentioned above. It would seem that everything is conducive to a successful performance: the artist feels good, he is internally calm, balanced, almost confident in his own abilities. And the concert is colorless. There is no emotional current. And listener feedback, of course, too …

In short, it is necessary to debug, think over the daily routine on the eve of the performance – in particular, the diet – it is necessary.

But, of course, this is only one side of the matter. Rather external. Speaking by and large, the whole life of an artist – ideally – should be such that he is always, at any moment, ready to respond with his soul to the sublime, spiritualized, poetically beautiful. Probably, there is no need to prove that a person who is interested in art, who is fond of literature, poetry, painting, theater, is much more disposed to lofty feelings than an average person, all of whose interests are concentrated in the sphere of the ordinary, material, everyday.

Young artists often hear before their performances: “Don’t think about the audience! It interferes! Think on stage only about what you are doing yourself … “. Vlasenko says about this: “It is easy to advise …”. He is well aware of the complexity, ambiguity, duality of this situation:

“Is there an audience for me personally during a performance? Do I notice her? Yes and no. On the one hand, when you completely go into the performing process, it’s as if you don’t think about the audience. You completely forget about everything except what you do at the keyboard. And yet… Every concert musician has a certain sixth sense – “a sense of the audience”, I would say. And therefore, the reaction of those who are in the hall, the attitude of people towards you and your game, you constantly feel.

Do you know what is most important for me during a concert? And the most revealing? Silence. For everything can be organized – both advertising, and the occupancy of the premises, and applause, flowers, congratulations, and so on and so forth, everything except silence. If the hall froze, held its breath, it means that something is really happening on the stage – something significant, exciting …

When I feel during the game that I have captured the attention of the audience, it gives me a huge burst of energy. Serves as a kind of dope. Such moments are a great happiness for the performer, the ultimate of his dreams. However, like any great joy, this happens infrequently.

It happens that Lev Nikolayevich is asked: does he believe in stage inspiration – he, a professional artist, for whom performing in front of the public is essentially a job that has been performed regularly, on a large scale, for many years … “Of course, the word “inspiration” itself » utterly worn, stamped, worn out from frequent use. With all that, believe me, every artist is ready to almost pray for inspiration. The feeling here is one of a kind: as if you are the author of the music being performed; as if everything in it was created by you yourself. And how many new, unexpected, truly successful things are born at such moments on stage! And literally in everything – in the coloring of sound, phrasing, in rhythmic nuances, etc.

I will say this: it is quite possible to give a good, professionally solid concert even in the absence of inspiration. There are any number of such cases. But if inspiration comes to the artist, the concert can become unforgettable … “

As you know, there are no reliable ways to evoke inspiration on the stage. But it is possible to create conditions that, in any case, would be favorable to him, would prepare the appropriate ground, Lev Nikolayevich believes.

“First of all, one psychological nuance is important here. You need to know and believe: what you can do on stage, no one else will do. Let it not be so everywhere, but only in a certain repertoire, in the works of one or two or three authors – it doesn’t matter, that’s not the point. The main thing, I repeat, is the feeling itself: the way you play, the other will not play. He, this imaginary “other”, may have a stronger technique, a richer repertoire, more extensive experience – anything. But he, however, will not sing the phrase the way you do, he will not find such an interesting and subtle sound shade …

The feeling I’m talking about now must be familiar to a concert musician. It inspires, lifts up, helps in difficult moments on the stage.

I often think of my teacher Yakov Vladimirovich Flier. He always tried to cheer up the students – made them believe in themselves. In moments of doubt, when not everything went well with us, he somehow instilled good spirits, optimism, and a good creative mood. And this brought us, pupils of his class, an undoubted benefit.

I think that almost every artist who performs on a large concert stage is convinced in the depths of his soul that he plays a little better than others. Or, in any case, maybe he is able to play better … And there is no need to blame anyone for this – there is a reason for this self-adjustment.

… In 1988, a large international music festival took place in Santander (Spain). It attracted special attention of the public – among the participants were I. Stern, M. Caballe, V. Ashkenazy, and other prominent European and overseas artists. The concerts of Lev Nikolaevich Vlasenko were held with genuine success within the framework of this musical festival. Critics spoke admiringly of his talent, skill, his happy ability to “get carried away and captivate …” Performances in Spain, like Vlasenko’s other tours in the second half of the eighties, convincingly confirmed that interest in his art had not dulled. He is still in a prominent place in modern concert life, Soviet and foreign. But to keep this place is much more difficult than to win it.

G. Tsypin, 1990