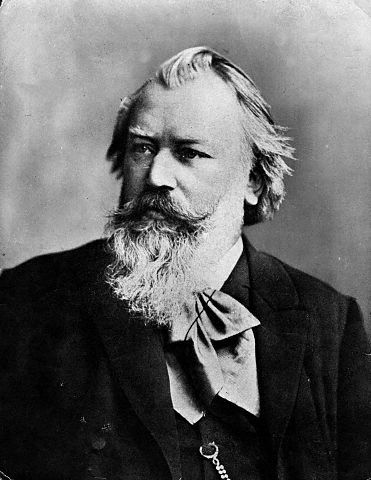

Johannes Brahms |

Johannes Brahms

As long as there are people who are capable of responding to music with all their hearts, and as long as it is precisely such a response that Brahms’ music will give rise to in them, this music will live on. G. Fire

Entering musical life as R. Schumann’s successor in romanticism, J. Brahms followed the path of broad and individual implementation of the traditions of different eras of German-Austrian music and German culture in general. During the period of development of new genres of program and theater music (by F. Liszt, R. Wagner), Brahms, who turned mainly to classical instrumental forms and genres, seemed to prove their viability and perspective, enriching them with the skill and attitude of a modern artist. Vocal compositions (solo, ensemble, choral) are no less significant, in which the range of coverage of tradition is especially felt – from the experience of Renaissance masters to modern everyday music and romantic lyrics.

Brahms was born into a musical family. His father, who went through a difficult path from a wandering artisan musician to a double bassist with the Hamburg Philharmonic Orchestra, gave his son initial skills in playing various stringed and wind instruments, but Johannes was more attracted to the piano. Successes in studies with F. Kossel (later – with the famous teacher E. Marksen) allowed him to take part in a chamber ensemble at the age of 10, and at 15 – to give a solo concert. From an early age, Brahms helped his father support his family by playing the piano in port taverns, making arrangements for the publisher Kranz, working as a pianist at the opera house, etc. Before leaving Hamburg (April 1853) on a tour with the Hungarian violinist E. Remenyi ( from folk tunes performed in concerts, the famous “Hungarian Dances” for piano in 4 and 2 hands were subsequently born), he was already the author of numerous works in various genres, mostly destroyed.

The very first published compositions (3 sonatas and a scherzo for pianoforte, songs) revealed the early creative maturity of the twenty-year-old composer. They aroused the admiration of Schumann, a meeting with whom in the autumn of 1853 in Düsseldorf determined the whole subsequent life of Brahms. Schumann’s music (its influence was especially direct in the Third Sonata – 1853, in the Variations on a Theme of Schumann – 1854 and in the last of the four ballads – 1854), the whole atmosphere of his home, the proximity of artistic interests (in his youth, Brahms, like Schumann, was fond of romantic literature – Jean-Paul, T. A. Hoffmann, and Eichendorff, etc.) had a huge impact on the young composer. At the same time, the responsibility for the fate of German music, as if entrusted by Schumann to Brahms (he recommended him to the Leipzig publishers, wrote an enthusiastic article about him “New Ways”), followed soon by a catastrophe (a suicide attempt made by Schumann in 1854, his stay in hospital for the mentally ill, where Brahms visited him, finally, Schumann’s death in 1856), a romantic feeling of passionate affection for Clara Schumann, whom Brahms devotedly helped in these difficult days – all this aggravated the dramatic intensity of Brahms’ music, its stormy spontaneity (First concerto for piano and orchestra – 1854-59; sketches of the First Symphony, the Third Piano Quartet, completed much later).

According to the way of thinking, Brahms at the same time was inherent in the desire for objectivity, for strict logical order, characteristic of the art of the classics. These features were especially strengthened with the move of Brahms to Detmold (1857), where he took the position of a musician at the princely court, led the choir, studied the scores of the old masters, G. F. Handel, J. S. Bach, J. Haydn and W. A. Mozart, created works in the genres characteristic of the music of the 2th century. (1857 orchestral serenades – 59-1860, choral compositions). Interest in choral music was also promoted by classes with an amateur women’s choir in Hamburg, where Brahms returned in 50 (he was very attached to his parents and his native city, but he never got a permanent job there that satisfied his aspirations). The result of creativity in the 60s – early 2s. chamber ensembles with the participation of the piano became large-scale works, as if replacing Brahms with symphonies (1862 quartets – 1864, Quintet – 1861), as well as variation cycles (Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Handel – 2, 1862 notebooks of Variations on a Theme of Paganini – 63-XNUMX ) are remarkable examples of his piano style.

In 1862, Brahms went to Vienna, where he gradually settled down for permanent residence. A tribute to the Viennese (including Schubert) tradition of everyday music were waltzes for piano in 4 and 2 hands (1867), as well as “Songs of Love” (1869) and “New Songs of Love” (1874) – waltzes for piano in 4 hands and a vocal quartet, where Brahms sometimes comes into contact with the style of the “king of waltzes” – I. Strauss (son), whose music he highly appreciated. Brahms is also gaining fame as a pianist (he performed since 1854, especially willingly played the piano part in his own chamber ensembles, played Bach, Beethoven, Schumann, his own works, accompanied singers, traveled to German Switzerland, Denmark, Holland, Hungary, to various German city), and after the performance in 1868 in Bremen of the “German Requiem” – his largest work (for choir, soloists and orchestra on texts from the Bible) – and as a composer. Strengthening the authority of Brahms in Vienna contributed to his work as the head of the choir of the Singing Academy (1863-64), and then the choir and orchestra of the Society of Music Lovers (1872-75). Brahms’ activities were intensive in editing piano works by W. F. Bach, F. Couperin, F. Chopin, R. Schumann for the publishing house Breitkopf and Hertel. He contributed to the publication of the works of A. Dvorak, then a little-known composer, who owed Brahms his warm support and participation in his fate.

Full creative maturity was marked by the appeal of Brahms to the symphony (First – 1876, Second – 1877, Third – 1883, Fourth – 1884-85). On the approaches to the implementation of this main work of his life, Brahms hones his skills in three string quartets (First, Second – 1873, Third – 1875), in orchestral Variations on a Theme of Haydn (1873). Images close to the symphonies are embodied in the “Song of Fate” (after F. Hölderlin, 1868-71) and in the “Song of the Parks” (after I. V. Goethe, 1882). The light and inspirational harmony of the Violin Concerto (1878) and the Second Piano Concerto (1881) reflected the impressions of trips to Italy. With its nature, as well as with the nature of Austria, Switzerland, Germany (Brahms usually composed in the summer months), the ideas of many of Brahms’ works are connected. Their spread in Germany and abroad was facilitated by the activities of outstanding performers: G. Bülow, conductor of one of the best in Germany, the Meiningen Orchestra; violinist I. Joachim (Brahms’s closest friend), leader of the quartet and soloist; singer J. Stockhausen and others. Chamber ensembles of various compositions (3 sonatas for violin and piano – 1878-79, 1886, 1886-88; Second sonata for cello and piano – 1886; 2 trios for violin, cello and piano – 1880-82 , 1886; 2 string quintets – 1882, 1890), Concerto for violin and cello and orchestra (1887), works for choir a cappella were worthy companions of symphonies. These are from the late 80s. prepared the transition to the late period of creativity, marked by the dominance of chamber genres.

Very demanding of himself, Brahms, fearing the exhaustion of his creative imagination, thought about stopping his composing activity. However, a meeting in the spring of 1891 with the clarinetist of the Meiningen Orchestra R. Mülfeld prompted him to create a Trio, a Quintet (1891), and then two sonatas (1894) with the clarinet. In parallel, Brahms wrote 20 piano pieces (op. 116-119), which, together with clarinet ensembles, became the result of the composer’s creative search. This is especially true of the Quintet and the piano intermezzo – “hearts of sorrowful notes”, combining the severity and confidence of the lyrical expression, the sophistication and simplicity of writing, the all-pervading melodiousness of intonations. The collection 1894 German Folk Songs (for voice and piano) published in 49 was evidence of Brahms’ constant attention to the folk song – his ethical and aesthetic ideal. Brahms was engaged in arrangements of German folk songs (including for the a cappella choir) throughout his life, he was also interested in Slavic (Czech, Slovak, Serbian) melodies, recreating their character in his songs based on folk texts. “Four Strict Melodies” for voice and piano (a kind of solo cantata on texts from the Bible, 1895) and 11 choral organ preludes (1896) supplemented the composer’s “spiritual testament” with an appeal to the genres and artistic means of the Bach era, just as close to the structure of his music, as well as folk genres.

In his music, Brahms created a true and complex picture of the life of the human spirit – stormy in sudden impulses, steadfast and courageous in overcoming obstacles internally, cheerful and cheerful, elegiacly soft and sometimes tired, wise and strict, tender and spiritually responsive. The craving for a positive resolution of conflicts, for relying on the stable and eternal values of human life, which Brahms saw in nature, folk song, in the art of the great masters of the past, in the cultural tradition of his homeland, in simple human joys, is constantly combined in his music with a sense of unattainability harmony, growing tragic contradictions. 4 symphonies of Brahms reflect different aspects of his attitude. In the First, a direct successor to Beethoven’s symphonism, the sharpness of the immediately flashing dramatic collisions is resolved in a joyful anthem finale. The second symphony, truly Viennese (at its origins – Haydn and Schubert), could be called a “symphony of joy.” The third – the most romantic of the entire cycle – goes from an enthusiastic intoxication with life to gloomy anxiety and drama, suddenly receding before the “eternal beauty” of nature, a bright and clear morning. The Fourth Symphony, the crowning achievement of Brahms’ symphonism, develops, according to I. Sollertinsky’s definition, “from elegy to tragedy.” The greatness erected by Brahms – the largest symphonist of the second half of the XIX century. – buildings does not exclude the general deep lyricism of tone inherent in all symphonies and which is the “main key” of his music.

E. Tsareva

Deep in content, perfect in skill, the work of Brahms belongs to the remarkable artistic achievements of German culture in the second half of the XNUMXth century. In a difficult period of its development, in the years of ideological and artistic confusion, Brahms acted as a successor and continuer classical traditions. He enriched them with the achievements of the German romanticism. Great difficulties arose along the way. Brahms sought to overcome them, turning to the comprehension of the true spirit of folk music, the richest expressive possibilities of the musical classics of the past.

“The folk song is my ideal,” said Brahms. Even in his youth, he worked with the rural choir; later he spent a long time as a choral conductor and, invariably referring to the German folk song, promoting it, processed it. That is why his music has such peculiar national features.

With great attention and interest, Brahms treated the folk music of other nationalities. The composer spent a significant part of his life in Vienna. Naturally, this led to the inclusion of nationally distinctive elements of Austrian folk art in Brahms’ music. Vienna also determined the great importance of Hungarian and Slavic music in the work of Brahms. “Slavicisms” are clearly perceptible in his works: in the frequently used turns and rhythms of the Czech polka, in some techniques of intonation development, modulation. The intonations and rhythms of Hungarian folk music, mainly in the style of verbunkos, that is, in the spirit of urban folklore, clearly affected a number of Brahms’s compositions. V. Stasov noted that the famous “Hungarian Dances” by Brahms are “worthy of their great glory.”

Sensitive penetration into the mental structure of another nation is available only to artists who are organically connected with their national culture. Such is Glinka in Spanish Overtures or Bizet in Carmen. Such is Brahms, the outstanding national artist of the German people, who turned to the Slavic and Hungarian folk elements.

In his declining years, Brahms dropped a significant phrase: “The two biggest events of my life are the unification of Germany and the completion of the publication of Bach’s works.” Here in the same row are, it would seem, incomparable things. But Brahms, usually stingy with words, put a deep meaning into this phrase. Passionate patriotism, a vital interest in the fate of the motherland, an ardent faith in the strength of the people naturally combined with a sense of admiration and admiration for the national achievements of German and Austrian music. The works of Bach and Handel, Mozart and Beethoven, Schubert and Schumann served as his guiding lights. He also closely studied ancient polyphonic music. Trying to better comprehend the patterns of musical development, Brahms paid great attention to issues of artistic skill. He entered Goethe’s wise words into his notebook: “Form (in art.— M. D.) is formed by thousands of years of efforts of the most remarkable masters, and the one who follows them, far from being able to master it so quickly.

But Brahms did not turn away from the new music: rejecting any manifestations of decadence in art, he spoke with a sense of true sympathy about many of the works of his contemporaries. Brahms highly appreciated the “Meistersingers” and much in the “Valkyrie”, although he had a negative attitude towards “Tristan”; admired the melodic gift and transparent instrumentation of Johann Strauss; spoke warmly of Grieg; the opera “Carmen” Bizet called his “favorite”; in Dvorak he found “a real, rich, charming talent.” Artistic tastes of Brahms show him as a lively, direct musician, alien to academic isolation.

This is how he appears in his work. It is full of exciting life content. In the difficult conditions of the German reality of the XNUMXth century, Brahms fought for the rights and freedom of the individual, sang of courage and moral stamina. His music is full of anxiety for the fate of a person, carries words of love and consolation. She has a restless, agitated tone.

The cordiality and sincerity of Brahms’ music, close to Schubert, are most fully revealed in the vocal lyrics, which occupies a significant place in his creative heritage. In the works of Brahms there are also many pages of philosophical lyrics, which are so characteristic of Bach. In developing lyrical images, Brahms often relied on existing genres and intonations, especially Austrian folklore. He resorted to genre generalizations, used dance elements of landler, waltz, and chardash.

These images are also present in the instrumental works of Brahms. Here, the features of drama, rebellious romance, passionate impetuosity are more pronounced, which brings him closer to Schumann. In the music of Brahms, there are also images imbued with vivacity and courage, courageous strength and epic power. In this area, he appears as a continuation of the Beethoven tradition in German music.

Acutely conflicting content is inherent in many chamber-instrumental and symphonic works of Brahms. They recreate exciting emotional dramas, often of a tragic nature. These works are characterized by the excitement of the narrative, there is something rhapsodic in their presentation. But freedom of expression in the most valuable works of Brahms is combined with the iron logic of development: he tried to clothe the boiling lava of romantic feelings in strict classical forms. The composer was overwhelmed with many ideas; his music was saturated with figurative richness, a contrasting change of moods, a variety of shades. Their organic fusion required a strict and precise work of thought, a high contrapuntal technique that ensured the connection of heterogeneous images.

But not always and not in all of his works Brahms managed to balance emotional excitement with the strict logic of musical development. those close to him romantic images sometimes clashed with classic presentation method. The disturbed balance sometimes led to vagueness, foggy complexity of expression, gave rise to unfinished, unsteady outlines of images; on the other hand, when the work of thought took precedence over emotionality, Brahms’ music acquired rational, passive-contemplative features. (Tchaikovsky saw only these, distant to him, sides in the work of Brahms and therefore could not correctly assess him. Brahms’ music, in his words, “as if teasing and irritating the musical feeling”; he found that it was dry, cold, foggy, indefinite. ).

But on the whole, his writings captivate with remarkable mastery and emotional immediacy in the transfer of significant ideas, their logically justified implementation. For, despite the inconsistency of individual artistic decisions, Brahms’ work is permeated with a struggle for the true content of music, for the high ideals of humanistic art.

Life and creative path

Johannes Brahms was born in the north of Germany, in Hamburg, on May 7, 1833. His father, originally from a peasant family, was a city musician (horn player, later double bass player). The composer’s childhood passed in need. From an early age, thirteen years old, he already performs as a pianist at dance parties. In the following years, he earns money with private lessons, plays as a pianist in theatrical intermissions, and occasionally participates in serious concerts. At the same time, having completed a composition course with a respected teacher Eduard Marksen, who instilled in him a love for classical music, he composes a lot. But the works of the young Brahms are not known to anyone, and for the sake of penny earnings, one has to write salon plays and transcriptions, which are published under various pseudonyms (about 150 opuses in total.) “Few lived as hard as I did,” said Brahms, recalling the years of his youth.

In 1853 Brahms left his native city; together with the violinist Eduard (Ede) Remenyi, a Hungarian political exile, he went on a long concert tour. This period includes his acquaintance with Liszt and Schumann. The first of them, with his usual benevolence, treated the hitherto unknown, modest and shy twenty-year-old composer. An even warmer reception awaited him at Schumann. Ten years have passed since the latter ceased to take part in the New Musical Journal he created, but, amazed by the original talent of Brahms, Schumann broke his silence – he wrote his last article entitled “New Ways”. He called the young composer a complete master who “perfectly expresses the spirit of the times.” The work of Brahms, and by this time he was already the author of significant piano works (among them three sonatas), attracted everyone’s attention: representatives of both the Weimar and Leipzig schools wanted to see him in their ranks.

Brahms wanted to stay away from the enmity of these schools. But he fell under the irresistible charm of the personality of Robert Schumann and his wife, the famous pianist Clara Schumann, for whom Brahms retained love and true friendship over the next four decades. The artistic views and convictions (as well as prejudices, in particular against Liszt!) of this remarkable couple were indisputable for him. And so, when in the late 50s, after the death of Schumann, an ideological struggle for his artistic heritage flared up, Brahms could not but take part in it. In 1860, he spoke in print (for the only time in his life!) against the assertion of the New German school that its aesthetic ideals were shared by all the best German composers. Due to an absurd accident, along with the name of Brahms, under this protest were the signatures of only three young musicians (including the outstanding violinist Josef Joachim, a friend of Brahms); the rest, more famous names were omitted in the newspaper. This attack, moreover, composed in harsh, inept terms, was met with hostility by many, Wagner in particular.

Shortly before that, Brahms’ performance with his First Piano Concerto in Leipzig was marked by a scandalous failure. Representatives of the Leipzig school reacted to him as negatively as the “Weimar”. Thus, abruptly breaking away from one coast, Brahms could not stick to the other. A courageous and noble man, he, despite the difficulties of existence and the cruel attacks of the militant Wagnerians, did not make creative compromises. Brahms withdrew into himself, fenced himself off from controversy, outwardly moved away from the struggle. But in his work he continued it: taking the best from the artistic ideals of both schools, with your music proved (albeit not always consistently) the inseparability of the principles of ideology, nationality and democracy as the foundations of life-truthful art.

The beginning of the 60s was, to a certain extent, a time of crisis for Brahms. After storms and fights, he gradually comes to the realization of his creative tasks. It was at this time that he began long-term work on major works of a vocal-symphonic plan (“German Requiem”, 1861-1868), on the First Symphony (1862-1876), intensively manifests himself in the field of chamber literature (piano quartets, quintet, cello sonata). Trying to overcome romantic improvisation, Brahms intensively studies folk song, as well as Viennese classics (songs, vocal ensembles, choirs).

1862 is a turning point in the life of Brahms. Finding no use for his strength in his homeland, he moves to Vienna, where he remains until his death. A wonderful pianist and conductor, he is looking for a permanent job. His hometown of Hamburg denied him this, inflicting a non-healing wound. In Vienna, he twice tried to gain a foothold in the service as the head of the Singing Chapel (1863-1864) and the conductor of the Society of Friends of Music (1872-1875), but left these positions: they did not bring him much artistic satisfaction or material security. Brahms’ position improved only in the mid-70s, when he finally received public recognition. Brahms performs a lot with his symphonic and chamber works, visits a number of cities in Germany, Hungary, Holland, Switzerland, Galicia, Poland. He loved these trips, getting to know new countries and, as a tourist, was eight times in Italy.

The 70s and 80s are the time of Brahms’ creative maturity. During these years, symphonies, violin and second piano concertos, many chamber works (three violin sonatas, second cello, second and third piano trios, three string quartets), songs, choirs, vocal ensembles were written. As before, Brahms in his work refers to the most diverse genres of musical art (with the exception of only musical drama, although he was going to write an opera). He strives to combine deep content with democratic intelligibility and therefore, along with complex instrumental cycles, he creates music of a simple everyday plan, sometimes for home music-making (vocal ensembles “Songs of Love”, “Hungarian Dances”, waltzes for piano, etc.). Moreover, working in both respects, the composer does not change his creative manner, using his amazing contrapuntal skill in popular works and without losing simplicity and cordiality in symphonies.

The breadth of Brahms’ ideological and artistic outlook is also characterized by a peculiar parallelism in solving creative problems. So, almost simultaneously, he wrote two orchestral serenades of different composition (1858 and 1860), two piano quartets (op. 25 and 26, 1861), two string quartets (op. 51, 1873); immediately after the end of the Requiem is taken for “Songs of Love” (1868-1869); along with the “Festive” creates the “Tragic Overture” (1880-1881); The first, “pathetic” symphony is adjacent to the second, “pastoral” (1876-1878); Third, “heroic” – with the Fourth, “tragic” (1883-1885) (In order to draw attention to the dominant aspects of the content of Brahms’ symphonies, their conditional names are indicated here.). In the summer of 1886, such contrasting works of the chamber genre as the dramatic Second Cello Sonata (op. 99), the light, idyllic in mood Second Violin Sonata (op. 100), the epic Third Piano Trio (op. 101) and passionately excited, pathetic Third Violin Sonata (op. 108).

Towards the end of his life – Brahms died on April 3, 1897 – his creative activity weakens. He conceived a symphony and a number of other major compositions, but only chamber pieces and songs were carried out. Not only did the range of genres narrow, the range of images narrowed. It is impossible not to see in this a manifestation of the creative fatigue of a lonely person, disappointed in the struggle of life. The painful illness that brought him to the grave (liver cancer) also had an effect. Nevertheless, these last years were also marked by the creation of truthful, humanistic music, glorifying high moral ideals. It suffices to cite as examples the piano intermezzos (op. 116-119), the clarinet quintet (op. 115), or the Four Strict Melodies (op. 121). And Brahms captured his unfading love for folk art in a wonderful collection of forty-nine German folk songs for voice and piano.

Features of style

Brahms is the last major representative of German music of the XNUMXth century, who developed the ideological and artistic traditions of the advanced national culture. His work, however, is not without some contradictions, because he was not always able to understand the complex phenomena of modernity, he was not included in the socio-political struggle. But Brahms never betrayed high humanistic ideals, did not compromise with bourgeois ideology, rejected everything false, transient in culture and art.

Brahms created his own original creative style. His musical language is marked by individual traits. Typical for him are intonations associated with German folk music, which affects the structure of themes, the use of melodies according to triad tones, and the plagal turns inherent in the ancient layers of songwriting. And plagality plays a big role in harmony; often, a minor subdominant is also used in a major, and a major in a minor. The works of Brahms are characterized by modal originality. The “flickering” of major – minor is very characteristic of him. So, the main musical motive of Brahms can be expressed by the following scheme (the first scheme characterizes the theme of the main part of the First Symphony, the second – a similar theme of the Third Symphony):

The given ratio of thirds and sixths in the structure of the melody, as well as the techniques of third or sixth doubling, are favorites of Brahms. In general, it is characterized by an emphasis on the third degree, the most sensitive in the coloring of the modal mood. Unexpected modulation deviations, modal variability, major-minor mode, melodic and harmonic major – all this is used to show the variability, the richness of the shades of the content. Complex rhythms, the combination of even and odd meters, the introduction of triplets, dotted rhythm, syncopation into a smooth melodic line also serve this.

Unlike rounded vocal melodies, Brahms’ instrumental themes are often open, which makes them difficult to memorize and perceive. Such a tendency to “open” thematic boundaries is caused by the desire to saturate music with development as much as possible. (Taneyev also aspired to this.). B. V. Asafiev rightly noted that Brahms even in lyrical miniatures “everywhere one feels development».

Brahms’ interpretation of the principles of shaping is marked by a special originality. He was well aware of the vast experience accumulated by European musical culture, and, along with modern formal schemes, he resorted to long ago, it would seem, out of use: such are the old sonata form, the variation suite, basso ostinato techniques; he gave a double exposure in concert, applied the principles of concerto grosso. However, this was not done for the sake of stylization, not for aesthetic admiration of obsolete forms: such a comprehensive use of established structural patterns was of a deeply fundamental nature.

In contrast to the representatives of the Liszt-Wagner trend, Brahms wanted to prove the ability old compositional means to transfer modern constructing thoughts and feelings, and practically, with his creativity, he proved this. Moreover, he considered the most valuable, vital means of expression, settled in classical music, as an instrument of struggle against the decay of form, artistic arbitrariness. An opponent of subjectivism in art, Brahms defended the precepts of classical art. He turned to them also because he sought to curb the unbalanced outburst of his own imagination, which overwhelmed his excited, anxious, restless feelings. He did not always succeed in this, sometimes significant difficulties arose in the implementation of large-scale plans. All the more insistently did Brahms creatively translate the old forms and established principles of development. He brought in a lot of new things.

Of great value are his achievements in the development of variational principles of development, which he combined with sonata principles. Based on Beethoven (see his 32 variations for piano or the finale of the Ninth Symphony), Brahms achieved in his cycles a contrasting, but purposeful, “through” dramaturgy. Evidence of this are the Variations on a theme by Handel, on a theme by Haydn, or the brilliant passacaglia of the Fourth Symphony.

In interpreting the sonata form, Brahms also gave individual solutions: he combined freedom of expression with the classical logic of development, romantic excitement with a strictly rational conduct of thought. The plurality of images in the embodiment of dramatic content is a typical feature of Brahms’ music. Therefore, for example, five themes are contained in the exposition of the first part of the piano quintet, the main part of the finale of the Third Symphony has three diverse themes, two side themes are in the first part of the Fourth Symphony, etc. These images are contrasted contrastingly, which is often emphasized by modal relationships ( for example, in the first part of the First Symphony, the side part is given in Es-dur, and the final part in es-moll; in the analogous part of the Third Symphony, when comparing the same parts A-dur – a-moll; in the finale of the named symphony – C-dur – c -moll, etc.).

Brahms paid special attention to the development of images of the main party. Her themes throughout the movement are often repeated without changes and in the same key, which is characteristic of the rondo sonata form. The ballad features of Brahms’ music also manifest themselves in this. The main party is sharply opposed to the final (sometimes linking), which is endowed with an energetic dotted rhythm, marching, often proud turns drawn from Hungarian folklore (see the first parts of the First and Fourth Symphonies, the Violin and Second Piano Concertos and others). Side parts, based on the intonations and genres of Viennese everyday music, are unfinished and do not become the lyrical centers of the movement. But they are an effective factor in development and often undergo major changes in development. The latter is held concisely and dynamically, as the development elements have already been introduced into the exposition.

Brahms was an excellent master of the art of emotional switching, of combining images of different qualities in a single development. This is helped by multilaterally developed motivic connections, the use of their transformation, and the widespread use of contrapuntal techniques. Therefore, he was extremely successful in returning to the starting point of the narrative – even within the framework of a simple tripartite form. This is all the more successfully achieved in the sonata allegro when approaching the reprise. Moreover, in order to exacerbate the drama, Brahms likes, like Tchaikovsky, to shift the boundaries of development and reprise, which sometimes leads to the rejection of the full performance of the main part. Correspondingly, the significance of the code as a moment of higher tension in the development of the part increases. Remarkable examples of this are found in the first movements of the Third and Fourth Symphonies.

Brahms is a master of musical dramaturgy. Both within the boundaries of one part, and throughout the entire instrumental cycle, he gave a consistent statement of a single idea, but, focusing all attention on internal logic of musical development, often neglected externally colorful expression of thought. Such is Brahms’ attitude to the problem of virtuosity; such is his interpretation of the possibilities of instrumental ensembles, the orchestra. He did not use purely orchestral effects and, in his predilection for full and thick harmonies, doubled the parts, combined voices, did not strive for their individualization and opposition. Nevertheless, when the content of the music required it, Brahms found the unusual flavor he needed (see the examples above). In such self-restraint, one of the most characteristic features of his creative method is revealed, which is characterized by a noble restraint of expression.

Brahms said: “We can no longer write as beautifully as Mozart, we will try to write at least as cleanly as he.” It is not only about technique, but also about the content of Mozart’s music, its ethical beauty. Brahms created music much more complex than Mozart, reflecting the complexity and inconsistency of his time, but he followed this motto, because the desire for high ethical ideals, a sense of deep responsibility for everything he did marked the creative life of Johannes Brahms.

M. Druskin

- Vocal creativity of Brahms →

- Chamber-instrumental creativity of Brahms →

- Symphonic works of Brahms →

Piano work of Brahms →

List of works by Brahms →