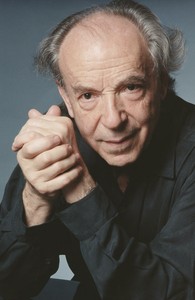

Jörg Demus |

Jörg Demus

The artistic biography of Demus is in many ways similar to the biography of his friend Paul Badur-Skoda: they are the same age, grew up and were brought up in Vienna, graduated from the Academy of Music here, and at the same time began to give concerts; both love and know how to play in ensembles and for a quarter of a century they have been one of the world’s most popular piano duets. There is much in common in their performing style, marked by balance, culture of sound, attention to detail and stylistic accuracy of the game, that is, the characteristic features of the modern Viennese school. Finally, the two musicians are brought closer by their repertory inclinations – both give a clear preference to the Viennese classics, persistently and consistently promote it.

But there are also differences. Badura-Skoda gained fame a little earlier, and this fame is based primarily on his solo concerts and performances with orchestras in all major centers of the world, as well as on his pedagogical activities and musicological works. Demus gives concerts not so widely and intensively (although he also traveled all over the world), he does not write books (although he owns the most interesting annotations for many recordings and publications). His reputation is based primarily on an original approach to interpreting problems and on the active work of an ensemble player: in addition to participating in a piano duet, he won the fame of one of the best accompanists in the world, performed with all the major instrumentalists and singers in Europe, and systematically accompanies the concerts of Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau.

All of the above does not mean that Demus does not deserve attention simply as a solo pianist. Back in 1960, when the artist performed in the United States, John Ardoin, a reviewer for Musical America magazine, wrote: “To say that Demus’ performance was solid and significant does not at all mean to belittle his dignity. It just explains why she left feeling warm and comfortable rather than uplifted. There was nothing whimsical or exotic in his interpretations, and no tricks. The music flowed freely and easily, in the most natural way. And this, by the way, is not at all easy to achieve. It takes a lot of self-control and experience, which is what an artist has.”

Demus is a crown to the marrow, and his interests are focused almost exclusively on Austrian and German music. Moreover, unlike Badur-Skoda, the center of gravity falls not on the classics (whom Demus plays a lot and willingly), but on the romantics. Back in the 50s, he was recognized as an outstanding interpreter of the music of Schubert and Schumann. Later, his concert programs consisted almost exclusively of works by Beethoven, Brahms, Schubert and Schumann, although sometimes they also included Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Mendelssohn. Another area that attracts the artist’s attention is Debussy’s music. So, in 1962, he surprised many of his admirers by recording “Children’s Corner”. Ten years later, unexpectedly for many, the complete collection – on eight records – of Debussy’s piano compositions, came out in Demus’ recordings. Here, not everything is equal, the pianist does not always have the necessary lightness, a flight of fancy, but, according to experts, “thanks to the fullness of sound, warmth and ingenuity, it is worthy to stand on a par with the best interpretations of Debussy.” And yet, the Austro-German classics and romance remain the main area of the creative search for a talented artist.

Of particular interest, starting from the 60s, are his recordings of works by Viennese masters, made on pianos dating back to their era, and, as a rule, in ancient palaces and castles with acoustics that help to recreate the atmosphere of primevalness. The appearance of the very first records with the works of Schubert (perhaps the author closest to Demus) was enthusiastically received by critics. “The sound is amazing – Schubert’s music becomes more restrained and yet more colorful, and, undoubtedly, these recordings are extremely instructive,” wrote one of the reviewers. “The greatest advantage of his Schumannian interpretations is their refined poetry. It reflects the pianist’s inner closeness to the world of the composer’s feelings and all German romance, which he conveys here without losing his face at all,” E. Kroer noted. And after the appearance of the disc with Beethoven’s early compositions, the press could read the following lines: “In the face of Demus, we found a performer whose smooth, thoughtful playing leaves an exceptional impression. So, judging by the memoirs of contemporaries, Beethoven himself could have played his sonatas.”

Since then, Demus has recorded dozens of different works on records (both on his own and in a duet with Badura-Skoda), using all the tools available to him from museums and private collections. Under his fingers, the heritage of the Viennese classics and romantics appeared in a new light, especially since a significant part of the recordings are rarely performed and little known compositions. In 1977, he, the second of the pianists (after E. Ney), was awarded the highest award of the Beethoven Society in Vienna – the so-called “Beethoven Ring”.

However, justice requires it to be noted that his numerous records do not at all cause unanimous delight, and the farther, the more often notes of disappointment are heard. Everyone, of course, pays tribute to the pianist’s skill, they note that he is able to show expressiveness and romantic flight, as if compensating for the dryness and lack of a real cantilena in old instruments; undeniable poetry, subtle musicality of his game. And yet, many agree with the claims recently made by the critic P. Kosse: “Jörg Demus’ recording activity contains something kaleidoscopic and disturbing: almost all small and large companies publish his records, double albums and voluminous cassettes, the repertoire extends from didactic pedagogical pieces to Beethoven’s late sonatas and Mozart’s concertos played on hammer-action pianos. All this is somewhat motley; anxiety arises when you pay attention to the average level of these records. The day contains only 24 hours, even such a gifted musician is hardly capable of approaching his work with equal responsibility and dedication, producing record after record.” Indeed, sometimes – especially in recent years – the results of Demus’s work are negatively affected by excessive haste, illegibility in the choice of repertoire, discrepancy between the capabilities of the instruments and the nature of the music performed; deliberately unpretentious, “conversational” style of interpretation sometimes leads to a violation of the internal logic of classical works.

Many music critics rightly advise Jörg Demus to expand his concert activities, more carefully “beat” his interpretations, and only after that fix them on a record.

Grigoriev L., Platek Ya., 1990