Heinrich Schütz |

Heinrich Schuetz

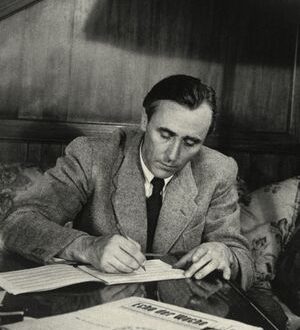

Schutz. Kleine geistliche konzerte. “O Herr, hilf” (orchestra and choir conducted by Wilhelm Echmann)

The joy of foreigners, the beacon of Germany, the chapel, the chosen Teacher. Inscription on the grave of G. Schütz in Dresden

H. Schutz occupies in German music the place of honor of the patriarch, “the father of new German music” (an expression of his contemporary). The gallery of great composers who brought world fame to Germany begins with it, and a direct path to J.S. Bach is also outlined.

Schutz lived in an era that was rare in terms of saturation with European and global events, a turning point, the beginning of a new countdown in history and culture. His long life included such milestones that speak of a break in times, ends and beginnings, such as the burning of G. Bruno, the abdication of G. Galileo, the beginning of the activities of I. Newton and G. V. Leibniz, the creation of Hamlet and Don Quixote. Schutz’s position at this time of change is not in the invention of the new, but in the synthesis of the richest layers of culture dating back to the Middle Ages, with the latest achievements that came then from Italy. He paved a new path of development for backward musical Germany.

German musicians saw Schutze as a Teacher, even without being his students in the literal sense of the word. Although the actual students who continued the work he started in different cultural centers of the country, he left a lot. Schutz did a lot to develop the musical life in Germany, advising, organizing and transforming a wide variety of chapels (there was no shortage of invitations). And this is in addition to his long work as a bandmaster in one of the first musical courts in Europe – in Dresden, and for several years – in the prestigious Copenhagen.

The teacher of all Germans, he continued to learn from others even in his mature years. So, he twice went to Venice to improve: in his youth he studied with the famous G. Gabrieli and already a recognized master mastered the discoveries of C. Monteverdi. An active musician-practitioner, business organizer and scientist, who left behind valuable theoretical works recorded by his beloved student K. Bernhard, Schutz was the ideal that contemporary German composers aspired to. He was distinguished by deep knowledge in various fields, in a wide range of his interlocutors were outstanding German poets M. Opitz, P. Fleming, I. Rist, as well as well-known lawyers, theologians, and natural scientists. It is curious that the final choice of the profession of a musician was made by Schütz only at the age of thirty, which, however, was also affected by the will of his parents, who dreamed of seeing him as a lawyer. Schütz even attended lectures on jurisprudence at the universities of Marburg and Leipzig.

The creative heritage of the composer is very large. About 500 compositions have survived, and this, as experts suggest, is only two-thirds of what he wrote. Schütz composed in spite of many hardships and losses until old age. At the age of 86, being on the verge of death and even taking care of the music that will sound at his funeral, he created one of his best compositions – “German Magnificat”. Although only Schutz’s vocal music is known, his legacy is surprising in its diversity. He is the author of exquisite Italian madrigals and ascetic evangelical stories, passionate dramatic monologues and magnificent majestic multi-choir psalms. He owns the first German opera, ballet (with singing) and oratorio. The main direction of his work, however, is associated with sacred music to the texts of the Bible (concerts, motets, chants, etc.), which corresponded to the peculiarities of German culture of that dramatic time for Germany and the needs of the widest sections of the people. After all, a significant part of the creative path of Schutz proceeded during the period of the Thirty Years’ War, fantastic in its cruelty and destructive power. According to a long Protestant tradition, he acted in his works primarily not as a musician, but as a mentor, a preacher, striving to awaken and strengthen high ethical ideals in his listeners, to oppose the horrors of reality with fortitude and humanity.

The objectively epic tone of many of Schutz’s works can sometimes seem too ascetic, dryish, but the best pages of his work still touch with purity and expression, grandeur and humanity. In this they have something in common with the canvases of Rembrandt – the artist, according to many, is familiar with Schutz and even made him the prototype of his “Portrait of a Musician”.

O. Zakharova