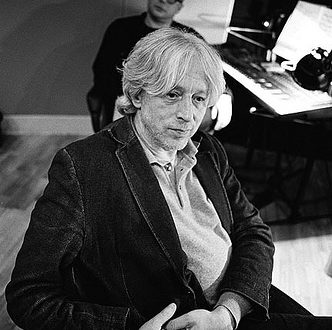

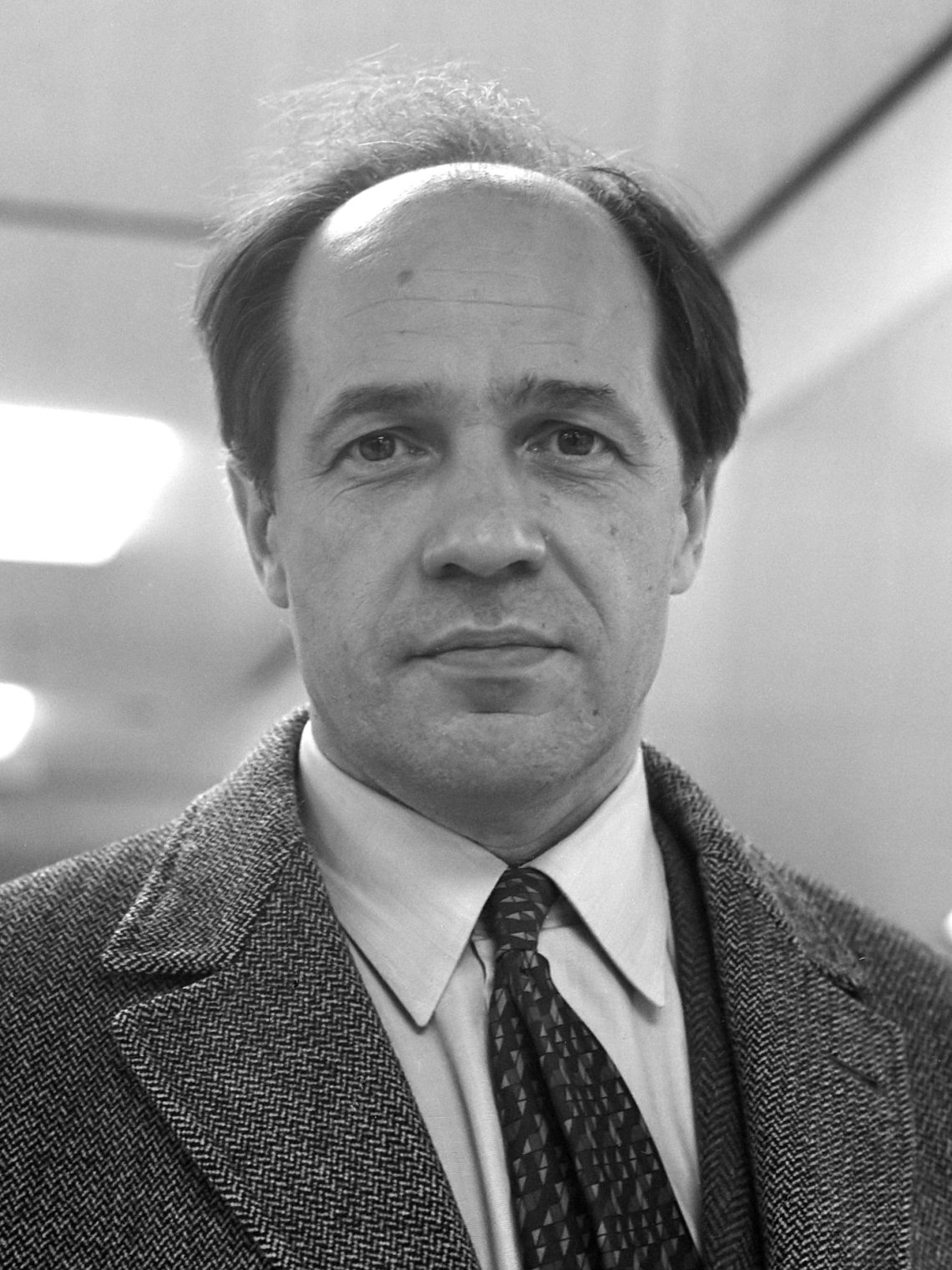

Pierre Boulez |

Pierre Boulez

In March 2000, Pierre Boulez turned 75 years old. According to one scathing British critic, the scale of the anniversary celebrations and the tone of the doxology would have embarrassed even Wagner himself: “to an outsider it might seem that we are talking about the true savior of the musical world.”

In dictionaries and encyclopedias, Boulez appears as a “French composer and conductor.” The lion’s share of the honors went, no doubt, to Boulez the conductor, whose activity has not diminished over the years. As for Boulez as a composer, over the past twenty years he has not created anything fundamentally new. Meanwhile, the influence of his work on post-war Western music can hardly be overestimated.

In 1942-1945, Boulez studied with Olivier Messiaen, whose composition class at the Paris Conservatory became perhaps the main “incubator” of avant-garde ideas in Western Europe liberated from Nazism (following Boulez, other pillars of the musical avant-garde – Karlheinz Stockhausen, Yannis Xenakis, Jean Barrake, György Kurtág, Gilbert Ami and many others). Messiaen conveyed to Boulez a special interest in the problems of rhythm and instrumental color, in non-European musical cultures, as well as in the idea of a form composed of separate fragments and not implying a consistent development. Boulez’s second mentor was Rene Leibovitz (1913–1972), a musician of Polish origin, a student of Schoenberg and Webern, a well-known theorist of the twelve-tone serial technique (dodecaphony); the latter was embraced by the young European musicians of Boulez’s generation as a genuine revelation, as an absolutely necessary alternative to the dogmas of yesterday. Boulez studied serial engineering under Leibowitz in 1945–1946. He soon made his debut with the First Piano Sonata (1946) and the Sonatina for Flute and Piano (1946), works of a relatively modest scale, made according to Schoenberg’s recipes. Other early opuses of Boulez are the cantatas The Wedding Face (1946) and The Sun of the Waters (1948) (both on verses by the outstanding surrealist poet René Char), the Second Piano Sonata (1948), The Book for String Quartet (1949) – were created under the joint influence of both teachers, as well as Debussy and Webern. The bright individuality of the young composer manifested itself, first of all, in the restless nature of the music, in its nervously torn texture and the abundance of sharp dynamic and tempo contrasts.

In the early 1950s, Boulez defiantly departed from the Schoenbergian orthodox dodecaphony taught to him by Leibovitz. In his obituary to the head of the new Viennese school, defiantly titled “Schoenberg is dead”, he declared Schoenberg’s music rooted in late Romanticism and therefore aesthetically irrelevant, and engaged in radical experiments in the rigid “structuring” of various parameters of music. In his avant-garde radicalism, the young Boulez sometimes clearly crossed the line of reason: even the sophisticated audience of international festivals of contemporary music in Donaueschingen, Darmstadt, Warsaw remained at best indifferent to such indigestible scores of his of this period as “Polyphony-X” for 18 instruments (1951) and the first book of Structures for two pianos (1952/53). Boulez expressed his unconditional commitment to new techniques for organizing sound material not only in his work, but also in articles and declarations. So, in one of his speeches in 1952, he announced that a modern composer who did not feel the need for serial technology, simply “nobody needs it.” However, very soon his views softened under the influence of acquaintance with the work of no less radical, but not so dogmatic colleagues – Edgar Varese, Yannis Xenakis, Gyorgy Ligeti; subsequently, Boulez willingly performed their music.

Boulez’s style as a composer has evolved towards greater flexibility. In 1954, from under his pen came “A Hammer without a Master” – a nine-part vocal-instrumental cycle for contralto, alto flute, xylorimba (xylophone with extended range), vibraphone, percussion, guitar and viola to words by René Char. There are no episodes in The Hammer in the usual sense; at the same time, the whole set of parameters of the sounding fabric of the work is determined by the idea of seriality, which denies any traditional forms of regularity and development and affirms the inherent value of individual moments and points of musical time-space. The unique timbre atmosphere of the cycle is determined by the combination of a low female voice and instruments close to it (alto) register.

In some places, exotic effects appear, reminiscent of the sound of the traditional Indonesian gamelan (percussion orchestra), the Japanese koto stringed instrument, etc. Igor Stravinsky, who highly appreciated this work, compared its sound atmosphere with the sound of ice crystals beating against the wall glass cup. The Hammer has gone down in history as one of the most exquisite, aesthetically uncompromising, exemplary scores from the heyday of the “great avant-garde”.

New music, especially so-called avant-garde music, is usually reproached for its lack of melody. With regard to Boulez, such a reproach is, strictly speaking, unfair. The unique expressiveness of his melodies is determined by the flexible and changeable rhythm, the avoidance of symmetrical and repetitive structures, rich and sophisticated melismatics. With all the rational “construction”, Boulez’s melodic lines are not dry and lifeless, but plastic and even elegant. Boulez’s melodic style, which took shape in opuses inspired by the fanciful poetry of René Char, was developed in “Two Improvisations after Mallarmé” for soprano, percussion and harp on the texts of two sonnets by the French symbolist (1957). Boulez later added a third improvisation for soprano and orchestra (1959), as well as a predominantly instrumental introductory movement “The Gift” and a grand orchestral finale with a vocal coda “The Tomb” (both to lyrics by Mallarme; 1959–1962). The resulting five-movement cycle, titled “Pli selon pli” (approximately translated “Fold by Fold”) and subtitled “Portrait of Mallarme”, was first performed in 1962. The meaning of the title in this context is something like this: the veil thrown over the portrait of the poet slowly, fold by fold, falls off as the music unfolds. The cycle “Pli selon pli”, which lasts about an hour, remains the composer’s most monumental, largest score. Contrary to the author’s preferences, I would like to call it a “vocal symphony”: it deserves this genre name, if only because it contains a developed system of musical thematic connections between parts and relies on a very strong and effective dramatic core.

As you know, the elusive atmosphere of Mallarmé’s poetry had an exceptional attraction for Debussy and Ravel.

Having paid tribute to the symbolist-impressionist aspect of the poet’s work in The Fold, Boulez focused on his most amazing creation – the posthumously published unfinished Book, in which “every thought is a roll of bones” and which, on the whole, resembles a “spontaneous scattering of stars”, that is, consists of autonomous, not linearly ordered, but internally interconnected artistic fragments. Mallarmé’s “Book” gave Boulez the idea of the so-called mobile form or “work in progress” (in English – “work in progress”). The first experience of this kind in the work of Boulez was the Third Piano Sonata (1957); its sections (“formants”) and individual episodes within sections can be performed in any order, but one of the formants (“constellation”) must certainly be in the center. The sonata was followed by Figures-Doubles-Prismes for orchestra (1963), Domaines for clarinet and six groups of instruments (1961-1968) and a number of other opuses that are still constantly reviewed and edited by the composer, since in principle they cannot be completed. One of the few relatively late Boulez scores with a given form is the solemn half-hour “Ritual” for large orchestra (1975), dedicated to the memory of the influential Italian composer, teacher and conductor Bruno Maderna (1920-1973).

From the very beginning of his professional career, Boulez discovered an outstanding organizational talent. Back in 1946, he took the post of musical director of the Paris theater Marigny (The’a ^ tre Marigny), headed by the famous actor and director Jean-Louis Barraud. In 1954, under the auspices of the theater, Boulez, together with German Scherkhen and Piotr Suvchinsky, founded the concert organization “Domain musical” (“The Domain of Music”), which he directed until 1967. Its goal was to promote ancient and modern music, and the Domain Musical chamber orchestra became a model for many ensembles performing music of the XNUMXth century. Under the direction of Boulez, and later his student Gilbert Amy, the Domaine Musical orchestra recorded on records many works by new composers, from Schoenberg, Webern and Varese to Xenakis, Boulez himself and his associates.

Since the mid-sixties, Boulez has stepped up his activities as an opera and symphony conductor of the “ordinary” type, not specializing in the performance of ancient and modern music. Accordingly, the productivity of Boulez as a composer declined significantly, and after the “Ritual” it stopped for several years. One of the reasons for this, along with the development of a conductor’s career, was the intensive work on the organization in Paris of a grandiose center for new music – the Institute of Musical and Acoustic Research, IRCAM. In the activities of IRCAM, of which Boulez was director until 1992, two cardinal directions stand out: the promotion of new music and the development of high sound synthesis technologies. The first public action of the institute was a cycle of 70 concerts of music of the 1977th century (1992). At the institute, there is a performing group “Ensemble InterContemporain” (“International Contemporary Music Ensemble”). At different times, the ensemble was headed by different conductors (since 1982, the Englishman David Robertson), but it is Boulez who is its generally recognized informal or semi-formal artistic director. IRCAM’s technological base, which includes state-of-the-art sound-synthesizing equipment, is made available to composers from all over the world; Boulez used it in several opuses, the most significant of which is “Responsorium” for instrumental ensemble and sounds synthesized on a computer (1990). In the XNUMXs, another large-scale Boulez project was implemented in Paris – the Cite’ de la musique concert, museum and educational complex. Many believe that Boulez’s influence on French music is too great, that his IRCAM is a sectarian-type institution that artificially cultivates a scholastic kind of music that has long lost its relevance in other countries. Further, the excessive presence of Boulez in the musical life of France explains the fact that modern French composers who do not belong to the Boulezian circle, as well as French conductors of the middle and young generation, fail to make a solid international career. But be that as it may, Boulez is famous and authoritative enough to, ignoring critical attacks, continue to do his job, or, if you like, pursue his policy.

If, as a composer and musical figure, Boulez evokes a difficult attitude towards himself, then Boulez as a conductor can be called with full confidence one of the largest representatives of this profession in the entire history of its existence. Boulez did not receive a special education, on the issues of conducting technique he was advised by conductors of the older generation devoted to the cause of new music – Roger Desormière, Herman Scherchen and Hans Rosbaud (later the first performer of “The Hammer without a Master” and the first two “Improvisations according to Mallarme”). Unlike almost all other “star” conductors of today, Boulez began as an interpreter of modern music, primarily his own, as well as his teacher Messiaen. Of the classics of the twentieth century, his repertoire was initially dominated by the music of Debussy, Schoenberg, Berg, Webern, Stravinsky (Russian period), Varese, Bartok. The choice of Boulez was often dictated not by spiritual closeness to one or another author or love for this or that music, but by considerations of an objective educational order. For example, he openly admitted that among the works of Schoenberg there are those that he does not like, but considers it his duty to perform, since he is clearly aware of their historical and artistic significance. However, such tolerance does not extend to all authors, who are usually included in the classics of new music: Boulez still considers Prokofiev and Hindemith to be second-rate composers, and Shostakovich is even third-rate (by the way, told by I. D. Glikman in the book “Letters to friend” the story of how Boulez kissed Shostakovich’s hand in New York is apocryphal; in fact, it was most likely not Boulez, but Leonard Bernstein, a well-known lover of such theatrical gestures).

One of the key moments in the biography of Boulez as a conductor was the highly successful production of Alban Berg’s opera Wozzeck at the Paris Opera (1963). This performance, starring superb Walter Berry and Isabelle Strauss, was recorded by CBS and is available to the modern listener on Sony Classical discs. By staging a sensational, still relatively new and unusual for that time, opera in the citadel of conservatism, which was considered the Grand Opera Theater, Boulez realized his favorite idea of integrating academic and modern performing practices. From here, one might say, began Boulez’s career as a Kapellmeister of the “ordinary” type. In 1966, Wieland Wagner, the composer’s grandson, opera director and manager known for his unorthodox and often paradoxical ideas, invited Boulez to Bayreuth to conduct Parsifal. A year later, on a tour of the Bayreuth troupe in Japan, Boulez conducted Tristan und Isolde (there is a video recording of this performance starring the exemplary 1960s Wagner couple Birgit Nilsson and Wolfgang Windgassen; Legato Classics LCV 005, 2 VHS; 1967).

Until 1978, Boulez repeatedly returned to Bayreuth to perform Parsifal, and the culmination of his Bayreuth career was the anniversary (on the 100th anniversary of the premiere) production of Der Ring des Nibelungen in 1976; the world press widely advertised this production as “The Ring of the Century”. In Bayreuth, Boulez conducted the tetralogy for the next four years, and his performances (in the provocative direction of Patrice Chereau, who sought to modernize the action) were recorded on discs and video cassettes by Philips (12 CD: 434 421-2 – 434 432-2 ; 7 VHS: 070407-3; 1981).

The seventies in the history of the opera were marked by another major event to which Boulez was directly involved: in the spring of 1979, on the stage of the Paris Opera, under his direction, the world premiere of the complete version of Berg’s opera Lulu took place (as is known, Berg died, leaving a larger part of the third act of the opera in sketches; the work on their orchestration, which became possible only after the death of Berg’s widow, was carried out by the Austrian composer and conductor Friedrich Cerha). Shero’s production was sustained in the usual sophisticated erotic style for this director, which, however, perfectly suited Berg’s opera with its hypersexual heroine.

In addition to these works, Boulez’s operatic repertoire includes Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, Bartók’s Castle of Duke Bluebeard, Schoenberg’s Moses and Aaron. The absence of Verdi and Puccini in this list is indicative, not to mention Mozart and Rossini. Boulez, on various occasions, has repeatedly expressed his critical attitude towards the operatic genre as such; apparently, something inherent in genuine, born opera conductors is alien to his artistic nature. Boulez’s opera recordings often produce an ambiguous impression: on the one hand, they recognize such “trademark” features of Boulez’s style as the highest rhythmic discipline, careful alignment of all relationships vertically and horizontally, unusually clear, distinct articulation even in the most complex textural heaps, with the other is that the selection of singers sometimes clearly leaves much to be desired. The studio recording of “Pelléas et Mélisande”, carried out in the late 1960s by CBS, is characteristic: the role of Pelléas, intended for a typically French high baritone, the so-called baritone-Martin (after the singer J.-B. Martin, 1768 –1837), for some reason entrusted to the flexible, but stylistically rather inadequate to his role, dramatic tenor George Shirley. The main soloists of the “Ring of the Century” – Gwyneth Jones (Brünnhilde), Donald McIntyre (Wotan), Manfred Jung (Siegfried), Jeannine Altmeyer (Sieglinde), Peter Hoffman (Siegmund) – are generally acceptable, but nothing more: they lack a bright individuality. More or less the same can be said about the protagonists of “Parsifal”, recorded in Bayreuth in 1970 – James King (Parsifal), the same McIntyre (Gurnemanz) and Jones (Kundry). Teresa Stratas is an outstanding actress and musician, but she does not always reproduce the complex coloratura passages in Lulu with due accuracy. At the same time, one cannot fail to note the magnificent vocal and musical skills of the participants in the second recording of Bartok’s “Duke Bluebeard’s Castle” made by Boulez – Jesse Norman and Laszlo Polgara (DG 447 040-2; 1994).

Before leading IRCAM and the Entercontamporen Ensemble, Boulez was Principal Conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra (1970–1972), the British Broadcasting Corporation Symphony Orchestra (1971–1974) and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra (1971–1977). With these bands, he made a number of recordings for CBS, now Sony Classical, many of which are, without exaggeration, enduring value. First of all, this applies to the collections of orchestral works by Debussy (on two discs) and Ravel (on three discs).

In the interpretation of Boulez, this music, without losing anything in terms of grace, softness of transitions, variety and refinement of timbre colors, reveals crystal transparency and purity of lines, and in some places also indomitable rhythmic pressure and wide symphonic breathing. Genuine masterpieces of the performing arts include the recordings of The Wonderful Mandarin, Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra, Five Pieces for Orchestra, Serenade, Schoenberg’s Orchestral Variations, and some scores by the young Stravinsky (however, Stravinsky himself was not too pleased with the earlier recording of The Rite of Spring, commenting on it like this: “This is worse than I expected, knowing the high level of Maestro Boulez’s standards”), Varese’s América and Arcana, all of Webern’s orchestral compositions …

Like his teacher Hermann Scherchen, Boulez does not use a baton and conducts in a deliberately restrained, businesslike manner, which – along with his reputation for writing cold, distilled, mathematically calculated scores – feeds the popular opinion of him as a performer of a purely objective warehouse, competent and reliable , but rather dry (even his incomparable interpretations of the Impressionists were criticized for being excessively graphic and, so to speak, insufficiently “impressionistic”). Such an assessment is completely inadequate to the scale of Boulez’s gift. Being the leader of these orchestras, Boulez performed not only Wagner and the music of the 4489th century, but also Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, Berlioz, Liszt… firms. For example, the Memories company released Schumann’s Scenes from Faust (HR 90/7), performed on March 1973, 425 in London with the participation of the BBC Choir and Orchestra and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau in the title role (by the way, shortly before this, the singer performed and “officially” recorded Faust at the Decca company (705 2-1972; XNUMX) under the direction of Benjamin Britten – the actual discoverer in the twentieth century of this late, uneven in quality, but in some places brilliant Schumann score). Far from exemplary quality of the recording does not prevent us from appreciating the grandeur of the idea and the perfection of its implementation; the listener can only envy those lucky ones who ended up in the concert hall that evening. The interaction between Boulez and Fischer-Dieskau – musicians, it would seem, so different in terms of talent – leaves nothing to be desired. The scene of Faust’s death sounds at the highest degree of pathos, and on the words “Verweile doch, du bist so schon” (“Oh, how wonderful you are, wait a bit!” – translated by B. Pasternak), the illusion of stopped time is amazingly achieved.

As head of IRCAM and Ensemble Entercontamporen, Boulez naturally paid a lot of attention to the latest music.

In addition to the works of Messiaen and his own, he especially willingly included in his programs the music of Elliot Carter, György Ligeti, György Kurtág, Harrison Birtwistle, relatively young composers of the IRCAM circle. He was and continues to be skeptical of fashionable minimalism and the “new simplicity”, comparing them with fast food restaurants: “convenient, but completely uninteresting.” Criticizing rock music for primitivism, for “an absurd abundance of stereotypes and clichés”, he nevertheless recognizes in it a healthy “vitality”; in 1984, he even recorded with the Ensemble Entercontamporen the disc “The Perfect Stranger” with music by Frank Zappa (EMI). In 1989, he signed an exclusive contract with Deutsche Grammophon, and two years later left his official position as head of IRCAM to devote himself entirely to composition and performances as a guest conductor. On Deutsche Grammo-phon, Boulez released new collections of orchestral music by Debussy, Ravel, Bartok, Webburn (with the Cleveland, Berlin Philharmonic, Chicago Symphony and London Symphony Orchestras); except for the quality of the recordings, they are in no way superior to previous CBS publications. Outstanding novelties include the Poem of Ecstasy, the Piano Concerto and Prometheus by Scriabin (pianist Anatoly Ugorsky is the soloist in the last two works); I, IV-VII and IX symphonies and Mahler’s “Song of the Earth”; Bruckner’s symphonies VIII and IX; “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” by R. Strauss. In Boulez’s Mahler, figurativeness, external impressiveness, perhaps, prevail over expression and the desire to reveal metaphysical depths. The recording of Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony, performed with the Vienna Philharmonic during the Bruckner celebrations in 1996, is very stylish and is by no means inferior to the interpretations of the born “Brucknerians” in terms of impressive sound build-up, grandiosity of climaxes, expressive richness of melodic lines, frenzy in the scherzo and sublime contemplation in the adagio . At the same time, Boulez fails to perform a miracle and somehow smooth out the schematism of Bruckner’s form, the merciless importunity of sequences and ostinato repetitions. Curiously, in recent years, Boulez has clearly softened his former hostile attitude towards Stravinsky’s “neoclassical” opuses; one of his best recent discs includes the Symphony of Psalms and the Symphony in Three Movements (with the Berlin Radio Choir and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra). There is hope that the range of the master’s interests will continue to expand, and, who knows, perhaps we will still hear works by Verdi, Puccini, Prokofiev and Shostakovich performed by him.

Levon Hakopyan, 2001