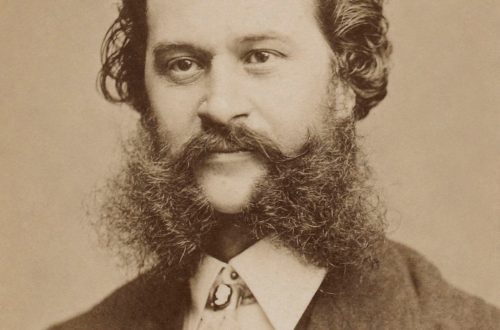

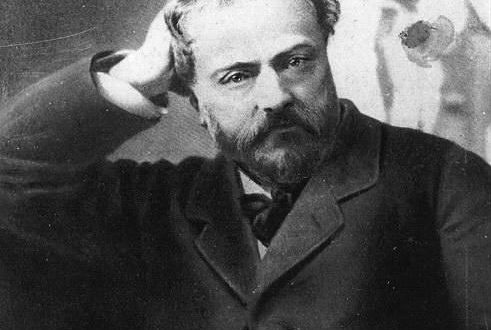

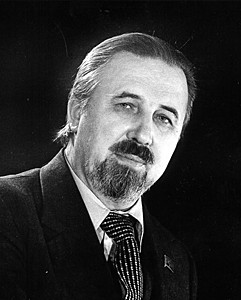

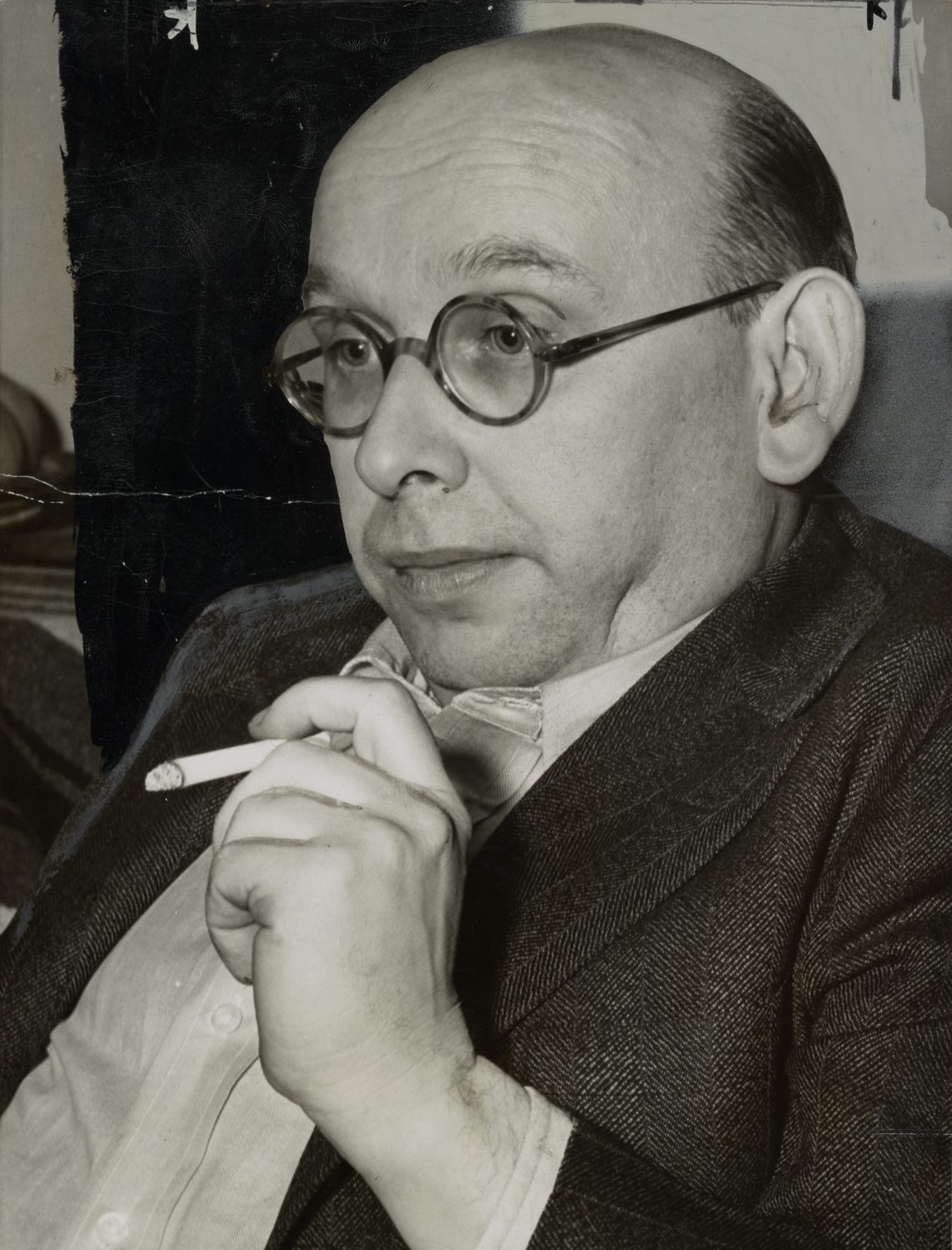

Hanns Eisler |

Hanns Eisler

At the end of the 20s, the militant mass songs of Hans Eisler, a communist composer who later played an outstanding role in the history of revolutionary song of the XNUMXth century, began to spread in the working-class districts of Berlin, and then in wide circles of the German proletariat. In collaboration with the poets Bertolt Brecht, Erich Weinert, singer Ernst Busch, Eisler introduces a new type of song into everyday life – a slogan song, a poster song calling for the struggle against the world of capitalism. This is how a song genre arises, which has acquired the name “Kampflieder” – “songs of the struggle.” Eisler came to this genre in a difficult way.

Hans Eisler was born in Leipzig, but did not live here for long, only four years. He spent his childhood and youth in Vienna. Music lessons began at an early age, at the age of 12 he tries to compose. Without the help of teachers, learning only from the examples of music known to him, Eisler wrote his first compositions, marked by the stamp of dilettantism. As a young man, Eisler joins a revolutionary youth organization, and when the First World War began, he actively participates in the creation and distribution of propaganda literature directed against the war.

He was 18 years old when he went to the front as a soldier. Here, for the first time, music and revolutionary ideas crossed in his mind, and the first songs arose – responses to the reality surrounding him.

After the war, returning to Vienna, Eisler entered the conservatory and became a student of Arnold Schoenberg, the creator of the dodecaphonic system, designed to destroy the centuries-old principles of musical logic and materialistic musical aesthetics. In the pedagogical practice of those years, Schoenberg turned exclusively to classical music, guiding his students to compose according to strict canonical rules that have deep traditions.

The years spent in Schoenberg’s class (1918-1923) gave Eisler the opportunity to learn the basics of composing technique. In his piano sonatas, Quintet for wind instruments, choirs on Heine’s verses, exquisite miniatures for voice, flute, clarinet, viola and cello, both a confident manner of writing and layers of heterogeneous influences are evident, first of all, naturally, the influence of the teacher, Schoenberg.

Eisler closely converges with the leaders of the amateur choral art, which is very developed in Austria, and soon becomes one of the most passionate champions of mass forms of musical education in the working environment. The thesis “Music and Revolution” becomes decisive and indestructible for the rest of his life. That is why he feels an inner need to revise the aesthetic positions instilled by Schoenberg and his entourage. At the end of 1924, Eisler moved to Berlin, where the pulse of the life of the German working class beats so intensely, where the influence of the Communist Party is growing every day, where the speeches of Ernst Thalmann perspicaciously indicate to the working masses what danger is fraught with the ever more active reaction, heading towards fascism.

Eisler’s first performances as a composer caused a real scandal in Berlin. The reason for it was the performance of a vocal cycle on texts borrowed from newspaper ads. The task that Eisler set for himself was clear: by deliberate prosaism, by everydayness, to inflict a “slap in the face of public taste”, meaning the tastes of the townsfolk, philistines, as Russian futurists practiced in their literary and oral speeches. Critics reacted appropriately to the performance of “Newspaper Ads”, not stinting in the choice of swear words and insulting epithets.

Eisler himself treated the episode with the “Announcements” quite ironically, realizing that the excitement of a commotion and scandals in a philistine swamp should hardly be considered a serious event. Continuing the friendship he had begun in Vienna with amateur workers, Eisler received much broader opportunities in Berlin, linking his activities with the Marxist workers’ school, one of the centers of ideological work organized by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Germany. It is here that his creative friendship with poets Bertolt Brecht and Erich Weinert, with composers Karl Rankl, Vladimir Vogl, Ernst Meyer is established.

It should be remembered that the end of the 20s was the time of the total success of jazz, a novelty that appeared in Germany after the war of 1914-18. Eisler is attracted to the jazz of those times not by sentimental sighs, not by the sensual languor of the slow foxtrot, and not by the bustle of the then fashionable shimmy dance – he highly appreciates the clarity of the jerky rhythm, the indestructible canvas of the marching grid, on which the melodic pattern stands out clearly. This is how Eisler’s songs and ballads arise, approaching in their melodic outlines in some cases to speech intonations, in others – to German folk songs, but always based on the complete submission of the performer to the iron tread of rhythm (most often marching), on pathetic, oratorical dynamics. Huge popularity is won by such songs as “Comintern” (“Factories, get up!”), “Song of Solidarity” to the text of Bertolt Brecht:

Let the peoples of the earth rise, To unite their strength, To become a free land Let the earth feed us!

Or such songs as “Songs of the Cotton Pickers”, “Swamp Soldiers”, “Red Wedding”, “The Song of Stale Bread”, which gained fame in most countries of the world and experienced the fate of a truly revolutionary art: the affection and love of certain social groups and the hatred of their class antagonists.

Eisler also turns to a more extended form, to a ballad, but here he does not pose purely vocal difficulties for the performer – tessitura, tempo. Everything is decided by passion, pathos of interpretation, of course, in the presence of appropriate vocal resources. This performing style is most indebted to Ernst Busch, a man like Eisler who devoted himself to music and revolution. A dramatic actor with a wide range of images embodied by him: Iago, Mephistopheles, Galileo, heroes of plays by Friedrich Wolf, Bertolt Brecht, Lion Feuchtwanger, Georg Buchner – he had a peculiar singing voice, a baritone of a high metallic timbre. An amazing sense of rhythm, perfect diction, combined with the acting art of impersonation, helped him create a whole gallery of social portraits in various genres – from a simple song to a dithyramb, pamphlet, oratorical propaganda speech. It is difficult to imagine a more exact match between the composer’s intention and the performing embodiment than the Eisler-Bush ensemble. Their joint performance of the ballad “Secret Campaign Against the Soviet Union” (This ballad is known as “Anxious March”) and “Ballads of the Disabled War” made an indelible impression.

The visits of Eisler and Bush to the Soviet Union in the 30s, their meetings with Soviet composers, writers, conversations with A. M. Gorky left a deep impression not only in memoirs, but also in real creative practice, since many performers adopted style features Bush’s interpretations, and composers – Eisler’s specific style of writing. Such different songs as “Polyushko-field” by L. Knipper, “Here the soldiers are coming” by K. Molchanov, “Buchenwald alarm” by V. Muradeli, “If the boys of the whole earth” by V. Solovyov-Sedoy, with all their originality, inherited Eisler’s harmonic, rhythmic, and somewhat melodic formulas.

The coming of the Nazis to power drew a line of demarcation in the biography of Hans Eisler. On one side was that part of it that was associated with Berlin, with ten years of intense party and composer activity, on the other – years of wandering, fifteen years of emigration, first in Europe and then in the USA.

When in 1937 the Spanish Republicans raised the banner of struggle against the fascist gangs of Mussolini, Hitler and their own counter-revolution, Hans Eisler and Ernst Busch found themselves in the ranks of the Republican detachments shoulder to shoulder with volunteers who rushed from many countries to help the Spanish brothers. Here, in the trenches of Guadalajara, Campus, Toledo, songs just composed by Eisler were heard. His “March of the Fifth Regiment” and “Song of January 7” were sung by all of Republican Spain. Eisler’s songs sounded the same intransigence as Dolores Ibarruri’s slogans: “Better to die standing than to live on your knees.”

And when the combined forces of fascism strangled Republican Spain, when the threat of world war became real, Eisler moved to America. Here he gives his strength to pedagogy, concert performances, composing film music. In this genre, Eisler began to work especially intensively after moving to the major center of American cinema – Los Angeles.

And, although his music was highly appreciated by filmmakers and even received official awards, although Eisler enjoyed the friendly support of Charlie Chaplin, his life in the States was not sweet. The communist composer did not arouse the sympathy of officials, especially among those who, on duty, had to “follow the ideology.”

Longing for Germany is reflected in many of Eisler’s works. Perhaps the strongest thing is in the tiny song “Germany” to the verses of Brecht.

End of my sorrow You’re away now twilight shrouded Heaven is yours. A new day will come Do you remember more than once The song that the exile sang In this bitter hour

The melody of the song is close to German folklore and at the same time to songs that grew up on the traditions of Weber, Schubert, Mendelssohn. The crystal clearness of the melody leaves no doubt from what spiritual depths this melodic stream flowed.

In 1948, Hans Eisler was included in the lists of “undesirable foreigners,” was the accusation. As one researcher points out, “A McCarthyist official called him the Karl Marx of music. The composer was imprisoned.” And after a short time, despite the intervention and efforts of Charlie Chaplin, Pablo Picasso and many other major artists, the “country of freedom and democracy” sent Hans Eisler to Europe.

The British authorities tried to keep up with their overseas colleagues and refused Eisler hospitality. For some time Eisler lives in Vienna. He moved to Berlin in 1949. The meetings with Bertolt Brecht and Ernst Busch were exciting, but the most exciting was the meeting with the people who sang both Eisler’s old pre-war songs and his new songs. Here in Berlin, Eisler wrote a song to the lyrics of Johannes Becher “We will rise from the ruins and build a bright future”, which was the National Anthem of the German Democratic Republic.

Eisler’s 1958th birthday was solemnly celebrated in 60. He continued to write a lot of music for theater and cinema. And again, Ernst Busch, who miraculously escaped from the dungeons of the Nazi concentration camps, sang the songs of his friend and colleague. This time “Left March” to the verses of Mayakovsky.

On September 7, 1962, Hans Eisler died. His name was given to the Higher School of Music in Berlin.

Not all works are named in this short essay. The priority is given to the song. At the same time, Eisler’s chamber and symphonic music, his witty musical arrangements for Bertolt Brecht’s performances, and music for dozens of films entered not only Eisler’s biography, but also the history of the development of these genres. The pathos of citizenship, fidelity to the ideals of the revolution, the will and talent of the composer, who knows his people and sings along with them – all this gave irresistibility to his songs, the composer’s mighty weapon.