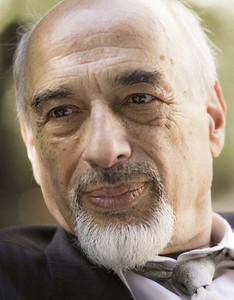

Grigory Lipmanovich Sokolov (Grigory Sokolov) |

Grigory Sokolov

There is an old parable about a traveler and a wise man who met on a deserted road. “Is it far to the nearest town?” the traveler asked. “Go,” the sage answered curtly. Surprised at the taciturn old man, the traveler was about to move on, when he suddenly heard from behind: “You will get there in an hour.” “Why didn’t you answer me right away? “I should have looked speed whether your step.

- Piano music in the Ozon online store →

How important it is – how fast is the step … Indeed, it doesn’t happen that an artist is judged only by his performance at some competition: did he show off his talent, technical skill, training, etc. They make forecasts, make guesses about his future, forgetting that the main thing is his next step. Will it be smooth and fast enough. Grigory Sokolov, the gold medalist of the Third Tchaikovsky Competition (1966), had a quick and confident next step.

His performance on the Moscow stage will remain in the annals of competition history for a long time. This really doesn’t happen very often. At first, in the first round, some of the experts did not hide their doubts: was it even worth including such a young musician, a student of the ninth grade of the school, among the contestants? (When Sokolov came to Moscow to participate in the Third Tchaikovsky Competition, he was only sixteen years old.). After the second stage of the competition, the names of the American M. Dichter, his compatriots J. Dick and E. Auer, the Frenchman F.-J. Thiolier, Soviet pianists N. Petrov and A. Slobodyanik; Sokolov was mentioned only briefly and in passing. After the third round, he was declared the winner. Moreover, the sole winner, who did not even share his award with someone else. For many, this was a complete surprise, including himself. (“I remember well that I went to Moscow, to the competition, just to play, to try my hand. I didn’t count on any sensational triumphs. Probably, this is what helped me …”) (A symptomatic statement, in many ways echoing the memoirs of R. Kerer. In psychological terms, judgments of this kind are of undeniable interest. – G. Ts.)

Some people at that time did not leave doubts – is it true, is the decision of the jury fair? The future answered yes to this question. It always brings final clarity to the results of competitive battles: what turned out to be legitimate in them, justified itself, and what did not.

Grigory Lipmanovich Sokolov received his musical education at a special school at the Leningrad Conservatory. His teacher in the piano class was L.I. Zelikhman, he studied with her for about eleven years. In the future, he studied with the famous musician, Professor M. Ya. Khalfin – he graduated from the conservatory under his leadership, then graduate school.

They say that from childhood Sokolov was distinguished by a rare industriousness. Already from the school bench, he was in a good way stubborn and persistent in his studies. And today, by the way, many hours of work at the keyboard (every day!) Is a rule for him, which he strictly observes. “Talent? This is love for one’s work, ”Gorky once said. One by one, how and how much Sokolov worked and continues to work, it was always clear that this was a real, great talent.

“Performing musicians are often asked how much time they devote to their studies,” says Grigory Lipmanovich. “The answers in these cases look, in my opinion, somewhat artificial. For it is simply impossible to calculate the rate of work, which would more or less accurately reflect the true state of affairs. After all, it would be naive to think that a musician works only during those hours when he is at the instrument. He is busy with his work all the time.…

If, nevertheless, to approach this issue more or less formally, then I would answer this way: on average, I spend at the piano about six hours a day. Although, I repeat, all this is very relative. And not only because day after day is not necessary. First of all, because playing an instrument and creative work as such are not the same things. There is no way to put an equal sign between them. The first is just some part of the second.

The only thing I would add to what has been said is that the more a musician does – in the broadest sense of the word – the better.

Let’s return to some facts of Sokolov’s creative biography and reflections connected with them. At the age of 12, he gave the first clavierabend in his life. Those who had a chance to visit it recall that already at that time (he was a sixth grade student) his playing captivated with the thoroughness of processing the material. Stopped the attention of that technical completeness, which gives a long, painstaking and intelligent work – and nothing else … As a concert artist, Sokolov always honored the “law of perfection” in the performance of music (the expression of one of the Leningrad reviewers), achieved strict observance of it on the stage. Apparently, this was not the least important reason that ensured his victory in the competition.

There was another one – the sustainability of creative results. During the Third International Forum of Performing Musicians in Moscow, L. Oborin stated in the press: “None of the participants, except G. Sokolov, went through all the tours without serious losses” (… Named after Tchaikovsky // Collection of articles and documents on the Third International Competition of Musicians-Performers named after P. I. Tchaikovsky. P. 200.). P. Serebryakov, who, together with Oborin, was a member of the jury, also drew attention to the same circumstance: “Sokolov,” he emphasized, “stood out among his rivals in that all stages of the competition went exceptionally smoothly” (Ibid., p. 198).

With regard to stage stability, it should be noted that Sokolov owes it in many respects to his natural spiritual balance. He is known in concert halls as a strong, whole nature. As an artist with a harmoniously ordered, unsplit inner world; such are almost always stable in creativity. Evenness in the very character of Sokolov; it makes itself felt in everything: in his communication with people, demeanor and, of course, in artistic activity. Even in the most crucial moments on the stage, as far as one can judge from the outside, neither endurance nor self-control change him. Seeing him at the instrument – unhurried, calm and self-confident – some ask the question: is he familiar with that chilling excitement that turns the stay on the stage almost into torment for many of his colleagues … Once he was asked about it. He replied that he usually gets nervous before his performances. And very thoughtfully, he added. But most often before entering the stage, before he starts to play. Then the excitement somehow gradually and imperceptibly disappears, giving way to enthusiasm for the creative process and, at the same time, businesslike concentration. He plunges headlong into pianistic work, and that’s it. From his words, in short, a picture emerged that can be heard from everyone who was born for the stage, open performances, and communication with the public.

That is why Sokolov went “exceptionally smoothly” through all the rounds of competitive tests in 1966, for this reason he continues to play with enviable evenness to this day …

The question may arise: why did the recognition at the Third Tchaikovsky Competition come to Sokolov immediately? Why did he become a leader only after the final round? How to explain, finally, that the birth of the gold medalist was accompanied by a well-known discord of opinions? The bottom line is that Sokolov had one significant “flaw”: he, as a performer, had almost no … shortcomings. It was difficult to reproach him, an excellently trained pupil of a special music school, in some way – in the eyes of some this was already a reproach. There was talk of the “sterile correctness” of his playing; she annoyed some people … He was not creatively debatable – this gave rise to discussions. The public, as you know, is not without wariness towards exemplary well-trained students; The shadow of this relationship fell on Sokolov as well. Listening to him, they recalled the words of V. V. Sofronitsky, which he once said in his hearts about young contestants: “It would be very good if they all played a little more incorrectly …” (Memories of Sofronitsky. S. 75.). Perhaps this paradox really had something to do with Sokolov – for a very short period.

And yet, we repeat, those who decided the fate of Sokolov in 1966 turned out to be right in the end. Often judged today, the jury looked into tomorrow. And guessed it.

Sokolov managed to grow into a great artist. Once, in the past, an exemplary schoolboy who attracted attention primarily with his exceptionally beautiful and smooth playing, he became one of the most meaningful, creatively interesting artists of his generation. His art is now truly significant. “Only that is beautiful that is serious,” says Dr. Dorn in Chekhov’s The Seagull; Sokolov’s interpretations are always serious, hence the impression they make on listeners. Actually, he was never lightweight and superficial in relation to art, even in his youth; today, a tendency to philosophy begins to emerge more and more noticeably in him.

You can see it from the way he plays. In his programs, he often puts the Twenty-ninth, Thirty-first and Thirty-second sonatas of Bthoven, Bach’s Art of Fugue cycle, Schubert’s B flat major sonata … The composition of his repertoire is indicative in itself, it is easy to notice a certain direction in it, trend in creativity.

However, it is not only that in the repertoire of Grigory Sokolov. It is now about his approach to the interpretation of music, about his attitude to the works he performs.

Once in a conversation, Sokolov said that for him there are no favorite authors, styles, works. “I love everything that can be called good music. And everything that I love, I would like to play … ”This is not just a phrase, as sometimes happens. The pianist’s programs include music from the beginning of the XNUMXth century to the middle of the XNUMXth. The main thing is that it is distributed fairly evenly in his repertoire, without the disproportion that could be caused by the dominance of any one name, style, creative direction. Above were the composers whose works he plays especially willingly (Bach, Beethoven, Schubert). You can put next to them Chopin (mazurkas, etudes, polonaises, etc.), Ravel (“Night Gaspard”, “Alborada”), Scriabin (First Sonata), Rachmaninoff (Third Concerto, Preludes), Prokofiev (First Concerto, Seventh Sonata ), Stravinsky (“Petrushka”). Here, in the above list, what is most often heard at his concerts today. Listeners, however, have the right to expect new interesting programs from him in the future. “Sokolov plays a lot,” testifies the authoritative critic L. Gakkel, “his repertoire is growing rapidly …” (Gakkel L. About the Leningrad pianists // Sov. music. 1975. No. 4. P. 101.).

…Here he is shown from behind the scenes. Slowly walks across the stage in the direction of the piano. Having made a restrained bow to the audience, he settles down comfortably with his usual leisurelyness at the keyboard of the instrument. At first, he plays music, as it may seem to an inexperienced listener, a little phlegmatic, almost “with laziness”; those who are not the first time at his concerts, guess that this is largely a form expressing his rejection of all fuss, a purely external demonstration of emotions. Like every outstanding master, it is interesting to watch him in the process of playing – this does a lot for understanding the inner essence of his art. His whole figure at the instrument – seating, performing gestures, stage behavior – gives rise to a sense of solidity. (There are artists who are respected for the mere way they carry themselves on the stage. It happens, by the way, and vice versa.) And by the nature of the sound of Sokolov’s piano, and by his special playful appearance, it is easy to recognize in him an artist prone to “epic in musical performance. “Sokolov, in my opinion, is a phenomenon of the “Glazunov” creative fold,” Ya. I. Zak once said. With all the conventionality, perhaps the subjectivity of this association, it apparently did not arise by chance.

It is usually not easy for artists of such a creative formation to determine what comes out “better” and what is “worse”, their differences are almost imperceptible. And yet, if you take a look at the concerts of the Leningrad pianist in previous years, one cannot fail to say about his performance of Schubert’s works (sonatas, impromptu, etc.). Along with Beethoven’s late opuses, they, by all accounts, occupied a special place in the artist’s work.

Schubert’s pieces, especially the Impromptu Op. 90 are among the popular examples of the piano repertoire. That is why they are difficult; taking on them, you need to be able to move away from the prevailing patterns, stereotypes. Sokolov knows how. In his Schubert, as, indeed, in everything else, genuine freshness and richness of musical experience captivates. There is not a shadow of what is called the pop “poshib” – and yet its flavor can so often be felt in overplayed plays.

There are, of course, other features that are characteristic of Sokolov’s performance of Schubert’s works – and not only them … This is a magnificent musical syntax that reveals itself in the relief outline of phrases, motives, intonations. It is, further, the warmth of colorful tone and color. And of course, his characteristic softness of sound production: when playing, Sokolov seems to caress the piano …

Since his victory at the competition, Sokolov has toured extensively. It was heard in Finland, Yugoslavia, Holland, Canada, the USA, Japan, and in a number of other countries of the world. If we add here frequent trips to the cities of the Soviet Union, it is not difficult to get an idea of the scale of his concert and performing practice. Sokolov’s press looks impressive: the materials published about him in the Soviet and foreign press are in most cases in major tones. Its merits, in a word, are not overlooked. When it comes to “but”… Perhaps, most often one can hear that the art of a pianist – with all its undeniable merits – sometimes leaves the listener somewhat reassured. It does not bring, as it seems to some of the critics, excessively strong, sharpened, burning musical experiences.

Well, not everyone, even among the great, well-known masters, is given the opportunity to fire … However, it is possible that qualities of this kind will still manifest themselves in the future: Sokolov, one must think, has a long and not at all straightforward creative path ahead. And who knows if the time will come when the spectrum of his emotions will sparkle with new, unexpected, sharply contrasting combinations of colors. When it will be possible to see high tragic collisions in his art, to feel in this art pain, sharpness, and complex spiritual conflict. Then, perhaps, such works as the E-flat-minor polonaise (Op. 26) or the C-minor Etude (Op. 25) by Chopin will sound somewhat different. So far, they impress almost first of all with the beautiful roundness of the forms, the plasticity of the musical pattern and the noble pianism.

Somehow, answering the question of what drives him in his work, what stimulates his artistic thought, Sokolov spoke as follows: “It seems to me that I will not be mistaken if I say that I receive the most fruitful impulses from areas that are not directly related to my profession. That is, some musical “consequences” are derived by me not from the actual musical impressions and influences, but from somewhere else. But where exactly, I don’t know. I can’t say anything definite about this. I only know that if there are no inflows, receipts from outside, if there is not enough “nutritional juices” – the development of the artist inevitably stops.

And I also know that a person who moves forward not only accumulates something taken, gleaned from the side; he certainly generates his own ideas. That is, he not only absorbs, but also creates. And this is probably the most important thing. The first without the second would have no meaning in art.”

About Sokolov himself, it can be said with certainty that he really creates music at the piano, creates in the literal and authentic sense of the word – “generates ideas”, to use his own expression. Now it is even more noticeable than before. Moreover, the creative principle in the pianist’s playing “breaks through”, reveals itself – this is the most remarkable thing! – despite the well-known restraint, the academic rigor of his performing manner. This is particularly impressive…

Sokolov’s creative energy was clearly felt when talking about his recent performances at a concert in the October Hall of the House of the Unions in Moscow (February 1988), the program of which included Bach’s English Suite No. 2 in A minor, Prokofiev’s Eighth Sonata and Beethoven’s Thirty-second Sonata. The last of these works attracted particular attention. Sokolov has been performing it for a long time. Nevertheless, he continues to find new and interesting angles in his interpretation. Today, the pianist’s playing evokes associations with something that, perhaps, goes beyond purely musical sensations and ideas. (Let us recall what he said earlier about the “impulses” and “influences” that are so important to him, leave such a noticeable mark in his art – for all that they come from spheres that do not directly connect with music.) Apparently, this is what gives of particular value to Sokolov’s current approach to Beethoven in general, and his opus 111 in particular.

So, Grigory Lipmanovich willingly returns to the works that he previously performed. In addition to the Thirty-Second Sonata, one could name Bach’s Golberg Variations and The Art of Fugue, Beethoven’s Thirty-three Variations on a Waltz by Diabelli (Op. 120), as well as some other things that sounded at his concerts in the mid and late eighties . However, he, of course, is working on a new one. He constantly and persistently masters repertoire layers that he has not touched before. “This is the only way to move forward,” he says. “At the same time, in my opinion, you need to work at the limit of your strength – spiritual and physical. Any “relief”, any indulgence to oneself would be tantamount to a departure from real, great art. Yes, experience accumulates over the years; however, if it facilitates the solution of a particular problem, it is only for a faster transition to another task, to another creative problem.

For me, learning a new piece is always intense, nervous work. Perhaps especially stressful – in addition to everything else – also because I do not divide the work process into any stages and stages. The play “develops” in the course of learning from zero – and up to the moment when it is taken to the stage. That is, the work is of a cross-cutting, undifferentiated character – regardless of the fact that I rarely manage to learn a piece without some interruptions, connected either with tours, or with the repetition of other plays, etc.

After the first performance of a work on stage, work on it continues, but already in the status of learned material. And so on as long as I play this piece at all.

… I remember that in the mid-sixties – the young artist had just entered the stage – one of the reviews addressed to him said: “On the whole, Sokolov the musician inspires rare sympathy … he is definitely filled with rich opportunities, and from his art you involuntarily expect a lot of beauty. Many years have passed since then. The rich possibilities with which the Leningrad pianist was filled opened wide and happily. But, most importantly, his art never ceases to promise much more beauty…

G. Tsypin, 1990