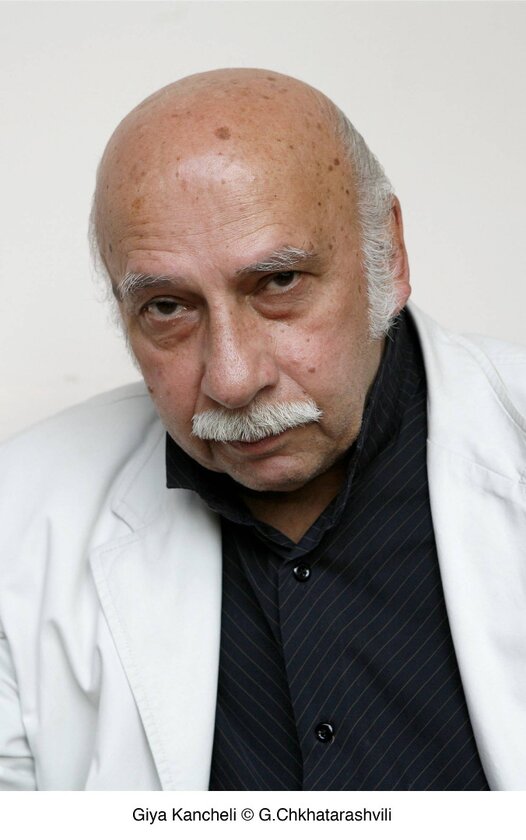

Giya Kancheli |

Giya Kancheli

A great musical talent, which occupies an absolutely original position internationally. L. Nono

An ascetic with the temperament of a maximalist, with the restraint of a hidden Vesuvius. R. Shchedrin

A master who knows how to say something new with the simplest means that cannot be confused with anything, perhaps even unique. W. Wolf

The originality of the music of G. Kancheli, to whom the above lines are dedicated, is combined with the utmost openness of style with its strictest selectivity, national soil with the universal significance of artistic ideas, the turbulent life of emotions with the sublimity of their expression, simplicity with depth, and accessibility with exciting novelty. Such a combination seems paradoxical only in verbal retelling, while the very formation of music by the Georgian author is always organic, welded together by a lively, song-like intonation by its nature. This is an artistically integral reflection of the modern world in its complex disharmony.

The composer’s biography is not too rich in external events. He grew up in Tbilisi, in the family of a doctor. Here he graduated from the seven-year musical school, then the geological faculty of the university, and only in 1963 – the conservatory in the composition class of I. Tuski. Already in his student years, Kancheli’s music was at the center of critical discussions that did not stop until the composer was awarded the USSR State Prize in 1976, and then flared up with renewed vigor. True, if at first Kancheli was reproached for eclecticism, for insufficiently vivid expression of his own individuality and national spirit, then later, when the author’s style was fully formed, they started talking about self-repetition. Meanwhile, even the first works of the composer revealed “his own understanding of musical time and musical space” (R. Shchedrin), and subsequently he followed the chosen path with enviable persistence, not allowing himself to stop or rest on what he had achieved. In each of his next works, Kancheli, according to his confession, seeks to “find for himself at least one step leading up, not down.” That is why he works slowly, spending several years finishing one work, and he usually continues editing the manuscript even after the premiere, right up to publication or recording on a record.

But among the few works of Kancheli, one cannot find experimental or passing ones, let alone unsuccessful ones. A prominent Georgian musicologist G. Ordzhonikidze likened his work to “climbing one mountain: from each height the horizon is thrown further, revealing previously unseen distances and allowing you to look into the depths of human existence.” A born lyricist, Kancheli rises through the objective balance of the epic to tragedy, without losing the sincerity and immediacy of the lyrical intonation. His seven symphonies are, as it were, seven re-lived lives, seven chapters of an epic about the eternal struggle between good and evil, about the difficult fate of beauty. Each symphony is a complete artistic whole. Different images, dramatic solutions, and yet all the symphonies form a kind of macrocycle with a tragic prologue (First – 1967) and “Epilogue” (Seventh – 1986), which, according to the author, sums up a large creative stage. In this macrocycle, the Fourth Symphony (1975), which was awarded the State Prize, is both the first climax and a harbinger of a turning point. Her two predecessors were inspired by the poetics of Georgian folklore, primarily church and ritual chants, rediscovered in the 60s. The second symphony, subtitled “Chants” (1970), is the brightest of Kancheli’s works, affirming the harmony of man with nature and history, the inviolability of the spiritual precepts of the people. The third (1973) is like a slender temple to the glory of the anonymous geniuses, the creators of the Georgian choral polyphony. The fourth symphony, dedicated to the memory of Michelangelo, while preserving the wholeness of the epic attitude through suffering, dramatizes him with reflections on the fate of the artist. Titan, who broke the shackles of time and space in his work, but turned out to be humanly powerless in the face of tragic existence. The Fifth Symphony (1978) is dedicated to the memory of the composer’s parents. Here, perhaps for the first time in Kancheli, the theme of time, inexorable and merciful, putting limits on human aspirations and hopes, is colored by deeply personal pain. And although all the images of the symphony – both mournful and desperately protesting – will sink or disintegrate under the onslaught of an unknown fatal force, the whole carries a feeling of catharsis. It is sorrow wept and overcome. After the performance of the symphony at the festival of Soviet music in the French city of Tours (July 1987), the press called it “perhaps the most interesting contemporary work to date.” In the Sixth Symphony (1979-81), the epic image of eternity reappears, the musical breath becomes wider, the contrasts grow larger. However, this does not smooth out, but sharpens and generalizes the tragic conflict. The triumphal success of the symphony at several reputable international music festivals was facilitated by its “super-daring conceptual scope and touching emotional impression.”

The arrival of the famous symphonist at the Tbilisi Opera House and the staging of “Music for the Living” here in 1984 came as a surprise to many. However, for the composer himself, this was a natural continuation of a long-standing and fruitful collaboration with the conductor J. Kakhidze, the first performer of all his works, and with the director of the Georgian Academic Drama Theater named after. Sh. Rustaveli R. Sturua. Having united their efforts on the opera stage, these masters also turned to a significant, urgent topic here – the theme of preserving life on earth, the treasures of world civilization – and embodied it in an innovative, large-scale, emotionally exciting form. “Music for the Living” is rightfully recognized as an event in the Soviet musical theater.

Immediately after the opera, Kancheli’s second anti-war work appeared – “Bright Sorrow” (1985) for soloists, children’s choir and large symphony orchestra to texts by G. Tabidze, I. V. Goethe, V. Shakespeare and A. Pushkin. Like “Music for the Living”, this work is dedicated to children – but not to those who will live after us, but to the innocent victims of the Second World War. Enthusiastically received already at the premiere in Leipzig (like the Sixth Symphony, it was written by order of the Gewandhaus orchestra and the Peters publishing house), Bright Sorrow became one of the most penetrating and sublime pages of Soviet music of the 80s.

The last of the composer’s completed scores – “Mourned by the Wind” for solo viola and large symphony orchestra (1988) – is dedicated to the memory of Givi Ordzhonikidze. This work premiered at the West Berlin Festival in 1989.

In the mid 60s. Kancheli begins cooperation with major directors of the drama theater and cinema. To date, he has written music for more than 40 films (mostly directed by E. Shengelaya, G. Danelia, L. Gogoberidze, R. Chkheidze) and almost 30 performances, the vast majority of which were staged by R. Sturua. However, the composer himself considers his work in the theater and cinema as just a part of collective creativity, which has no independent significance. Therefore, none of his songs, theatrical or film scores, has been published or recorded on a record.

N. Zeifas