Giacomo Meyerbeer |

Contents

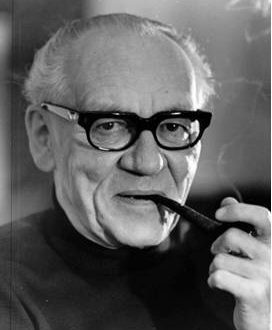

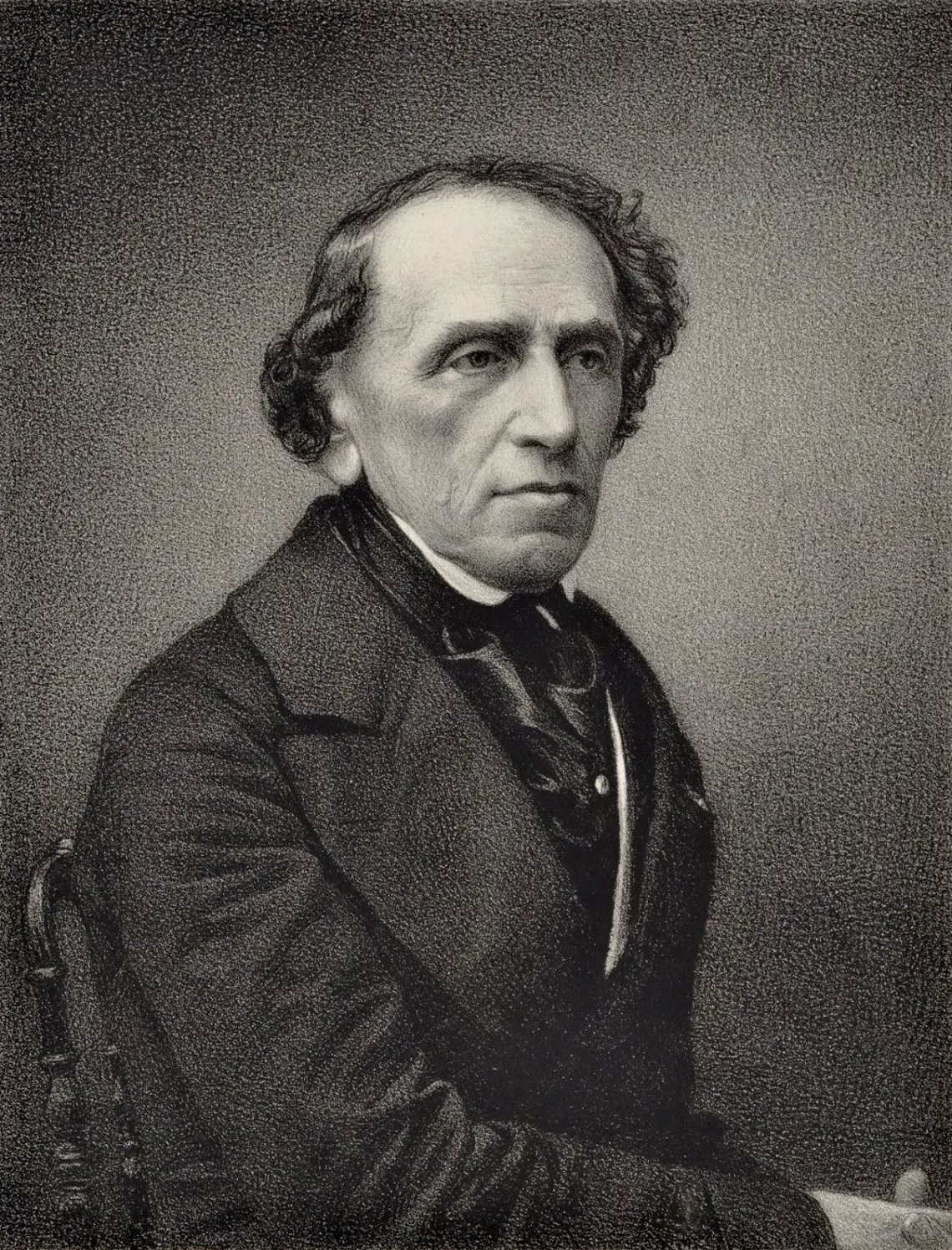

Giacomo Meyerbeer

The fate of J. Meyerbeer, the greatest opera composer of the XNUMXth century. – turned out happily. He did not have to earn his living, as did W. A. Mozart, F. Schubert, M. Mussorgsky and other artists, because he was born in the family of a major Berlin banker. He did not defend his right to creativity in his youth – his parents, very enlightened people who loved and understood art, did everything so that their children received the most brilliant education. The best teachers in Berlin instilled in them a taste for classical literature, history, and languages. Meyerbeer was fluent in French and Italian, knew Greek, Latin, Hebrew. The Giacomo brothers were also gifted: Wilhelm later became a famous astronomer, the younger brother, who died early, was a talented poet, the author of the Struensee tragedy, to which Meyerbeer subsequently wrote music.

Giacomo, the eldest of the brothers, began to study music at the age of 5. Having made tremendous progress, at the age of 9 he performs in a public concert with a performance of Mozart’s Concerto in D minor. The famous M. Clementi becomes his teacher, and the famous organist and theorist Abbot Vogler from Darmstadt, after listening to little Meyerbeer, advises him to study counterpoint and fugue with his student A. Weber. Later, Vogler himself invites Meyerbeer to Darmstadt (1811), where students from all over Germany came to the famous teacher. There Meyerbeer became friends with K. M. Weber, the future author of The Magic Shooter and Euryanta.

Among the first independent experiments of Meyerbeer are the cantata “God and Nature” and 2 operas: “Jephtha’s Oath” on a biblical story (1812) and a comic one, on the plot of a fairy tale from “A Thousand and One Nights”, “The Host and the Guest” (1813). Operas were staged in Munich and Stuttgart and were not successful. Critics reproached the composer for dryness and lack of a melodic gift. Weber consoled his fallen friend, and the experienced A. Salieri advised him to go to Italy to perceive the grace and beauty of melodies from its great masters.

Meyerbeer spends several years in Italy (1816-24). The music of G. Rossini reigns on the stages of Italian theaters, the premieres of his operas Tancred and The Barber of Seville are triumphant. Meyerbeer strives to learn a new style of writing. In Padua, Turin, Venice, Milan, his new operas are staged – Romilda and Constanza (1817), Semiramide Recognized (1819), Emma of Resburg (1819), Margherita of Anjou (1820), Exile from Grenada (1822) and, finally, the most striking opera of those years, The Crusader in Egypt (1824). It is successful not only in Europe, but also in the USA, in Brazil, some excerpts from it become popular.

“I didn’t want to imitate Rossini,” Meyerbeer asserts and seems to justify himself, “and write in Italian, as they say, but I had to write like that … because of my inner attraction.” Indeed, many of the composer’s German friends – and primarily Weber – did not welcome this Italian metamorphosis. The modest success of Meyerbeer’s Italian operas in Germany did not discourage the composer. He had a new goal: Paris – the largest political and cultural center at that time. In 1824, Meyerbeer was invited to Paris by none other than maestro Rossini, who did not then suspect that he was taking a step fatal to his fame. He even contributes to the production of The Crusader (1825), patronizing the young composer. In 1827, Meyerbeer moved to Paris, where he found his second home and where world fame came to him.

in Paris in the late 1820s. seething political and artistic life. The bourgeois revolution of 1830 was approaching. The liberal bourgeoisie was gradually preparing the liquidation of the Bourbons. The name of Napoleon is surrounded by romantic legends. The ideas of utopian socialism are spreading. Young V. Hugo in the famous preface to the drama “Cromwell” proclaims the ideas of a new artistic trend – romanticism. In the musical theater, along with the operas of E. Megul and L. Cherubini, the works of G. Spontini are especially popular. The images of the ancient Romans he created in the minds of the French have something in common with the heroes of the Napoleonic era. There are comic operas by G. Rossini, F. Boildieu, F. Aubert. G. Berlioz writes his innovative Fantastic Symphony. Progressive writers from other countries come to Paris – L. Berne, G. Heine. Meyerbeer carefully observes Parisian life, makes artistic and business contacts, attends theatrical premieres, among which are two landmark works for a romantic opera – Aubert’s The Mute from Portici (Fenella) (1828) and Rossini’s William Tell (1829). Significant was the composer’s meeting with the future librettist E. Scribe, an excellent connoisseur of the theater and the tastes of the public, a master of stage intrigue. The result of their collaboration was the romantic opera Robert the Devil (1831), which was a resounding success. Bright contrasts, live action, spectacular vocal numbers, orchestral sound – all this becomes characteristic of other Meyerbeer operas.

The triumphal premiere of The Huguenots (1836) finally crushes all his rivals. The loud fame of Meyerbeer also penetrates his homeland – Germany. In 1842, the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV invited him to Berlin as general music director. At the Berlin Opera, Meyerbeer receives R. Wagner for the production of The Flying Dutchman (the author conducts), invites Berlioz, Liszt, G. Marschner to Berlin, is interested in the music of M. Glinka and performs a trio from Ivan Susanin. In turn, Glinka writes: “The orchestra was directed by Meyerbeer, but we must admit that he is an excellent bandmaster in all respects.” For Berlin, the composer writes the opera Camp in Silesia (the main part is performed by the famous J. Lind), in Paris, The Prophet (1849), The North Star (1854), Dinora (1859) are staged. Meyerbeer’s last opera, The African Woman, saw the stage a year after his death, in 1865.

In his best stage works, Meyerbeer appears as the greatest master. A first-class musical talent, especially in the field of orchestration and melody, was not denied even by his opponents R. Schumann and R. Wagner. The virtuoso mastery of the orchestra allows it to achieve the finest picturesque and stunning dramatic effects (a scene in a cathedral, an episode of a dream, a coronation march in the opera The Prophet, or the consecration of swords in The Huguenots). No less skill and in the possession of choral masses. The influence of Meyerbeer’s work was experienced by many of his contemporaries, including Wagner in the operas Rienzi, The Flying Dutchman, and partly in Tannhäuser. Contemporaries were also captivated by the political orientation of Meyerbeer’s operas. In pseudo-historical plots, they saw the struggle of the ideas of today. The composer managed to subtly feel the era. Heine, who was enthusiastic about Meyerbeer’s work, wrote: “He is a man of his time, and time, which always knows how to choose its people, noisily raised him to the shield and proclaimed his dominance.”

E. Illeva

Compositions:

operas – Jephtha’s oath (The Jephtas Oath, Jephtas Gelübde, 1812, Munich), Host and guest, or a joke (Wirth und Gast oder Aus Scherz Ernst, 1813, Stuttgart; under the title Two caliphs, Die beyden Kalifen, 1814, “Kerntnertorteatr ”, Vienna; under the name Alimelek, 1820, Prague and Vienna), Brandenburg Gate (Das Brandenburger Tor, 1814, not permanent), Bachelor from Salamanca (Le bachelier de Salamanque, 1815 (?), not finished), Student from Strasbourg (L’etudiant de Strasbourg, 1815 (?), not finished), Robert and Elisa (1816, Palermo), Romilda and Constanta (melodrama, 1817, Padua), Recognized Semiramis (Semiramide riconsciuta, 1819, tr. “Reggio”, Turin), Emma of Resburg (1819, tr “San Benedetto”, Venice; under the name Emma Lester, or Voice of Conscience, Emma von Leicester oder Die Stimme des Gewissens, 1820, Dresden), Margaret of Anjou ( 1820, tr “La Scala”, Milan), Almanzor (1821, did not finish), Exile from Grenada (L’esule di Granada, 1822, tr “La Scala”, Milan), Crusader in Egypt (Il crociato in Egitto, 1824, tr Fenich e”, Venice), Ines di Castro, or Pedro of Portugal (Ines di Castro o sia Pietro di Portogallo, melodrama, 1825, not finished), Robert the Devil (Robert le Diable, 1831, “King. Academy of Music and Dance, Paris), Huguenots (Les Huguenots, 1835, post. 1836, ibid; in Russia under the name Guelphs and Ghibellines), Court Feast in Ferrara (Das Hoffest von Ferrara, a festive performance for the court carnival costumed Ball, 1843, Royal Palace, Berlin), Camp in Silesia (Ein Feldlager in Schlesien, 1844, “King. Spectacle”, Berlin), Noema, or Repentance (Nolma ou Le repentir, 1846, did not end.), Prophet ( Le prophète, 1849, King’s Academy of Music and Dance, Paris; in Russia under the name The Siege of Ghent, then John of Leiden), Northern Star (L’étoile du nord, 1854, Opera Comic, Paris) ; used the music of the opera Camp in Silesia), Judith (1854, did not end.), Ploermel forgiveness (Le pardon de Ploërmel, originally called Treasure Seeker, Le chercheur du tresor; also called Dinora, or Pilgrimage to Ploermel, Dinorah oder Die Wallfahrt nach Ploermel; 1859, tr Opera Comic, Paris), African (original name Vasco da Gama, 1864, post. 1865, Grand Opera, Steam izh); divertissement – Crossing the river, or the Jealous Woman (Le passage de la riviere ou La femme jalouse; also called The Fisherman and the Milkmaid, or A Lot of Noise Because of a Kiss, 1810, tr “King of the Spectacle”, Berlin); oratorio – God and nature (Gott und die Natur, 1811); for orchestra – Festive march to the coronation of William I (1861) and others; choirs – Psalm 91 (1853), Stabat Mater, Miserere, Te Deum, psalms, hymns for soloists and choir (not published); for voice and piano – St. 40 songs, romances, ballads (on verses by I. V. Goethe, G. Heine, L. Relshtab, E. Deschamps, M. Bera, etc.); music for drama theater performances, including Struenze (drama by M. Behr, 1846, Berlin), Youth of Goethe (La jeunesse de Goethe, drama by A. Blaze de Bury, 1859, not published).