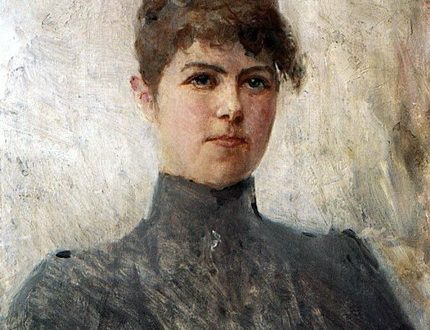

Francesca Cuzzoni |

Francesca Cuzzoni

One of the outstanding singers of the XNUMXth century, Cuzzoni-Sandoni, had a voice of a beautiful, soft timbre, she equally succeeded in complex coloratura and cantilena arias.

C. Burney quotes from the words of the composer I.-I. Quantz describes the singer’s virtues as follows: “Cuzzoni had a very pleasant and bright soprano voice, pure intonation and a beautiful trill; the range of her voice embraced two octaves – from one-quarter to three-quarter c. Her singing style was simple and full of feeling; her decorations did not seem artificial, thanks to the easy and precise manner with which she performed them; however, she captivated the hearts of the audience with her gentle and touching expression. In allegro she did not have great speed, but they were distinguished by completeness and smoothness of execution, polished and pleasant. However, with all these virtues, it must be admitted that she played rather coldly and that her figure was not very suitable for the stage.

Francesca Cuzzoni-Sandoni was born in 1700 in the Italian city of Parma, in a poor family of violinist Angelo Cuzzoni. She studied singing with Petronio Lanzi. She made her debut on the opera stage in 1716 in her native city. Later she sang in the theaters of Bologna, Venice, Siena with increasing success.

“Ugly, with an unbearable character, the singer nevertheless captivated the audience with her temperament, beauty of timbre, inimitable cantilena in the performance of the adagio,” writes E. Tsodokov. – Finally, in 1722, the prima donna receives an invitation from G.-F. Handel and his companion impresario Johann Heidegger to perform at the London Kingstier. The German genius, firmly established in the English capital, is trying to conquer “foggy Albion” with his Italian operas. He directs the Royal Academy of Music (designed to promote Italian opera) and competes with the Italian Giovanni Bononcini. The desire to get Cuzzoni is so great that even the harpsichordist of the theater Pietro Giuseppe Sandoni is sent for her to Italy. On the way to London, Francesca and her companion begin an affair that leads to an early marriage. Finally, on December 29, 1722, the British Journal announces the imminent arrival of the newly minted Cuzzoni-Sandoni in England, not forgetting to report her fee for the season, which is 1500 pounds (in reality, the prima donna received 2000 pounds).

On January 12, 1723, the singer made her London debut in the premiere of Handel’s opera Otto, King of Germany (Theophane part). Among Francesca’s partners is the famous Italian castrato Senesino, who has repeatedly performed with her. Performances in the premieres of Handel’s operas Julius Caesar (1724, the part of Cleopatra), Tamerlane (1724, the part of Asteria), and Rodelinda (1725, the title part) follow. In the future, Cuzzoni sang leading roles in London – both in Handel’s operas “Admet”, “Scipio and Alexander”, and in operas by other authors. Coriolanus, Vespasian, Artaxerxes and Lucius Verus by Ariosti, Calpurnia and Astyanax by Bononcini. And everywhere she was successful, and the number of fans grew.

The well-known scandalousness and obstinacy of the artist did not bother Handel, who had sufficient determination. Once the prima donna did not want to perform the aria from Ottone as the composer prescribed. Handel immediately promised Cuzzoni that in case of a categorical refusal, he would simply throw her out the window!

After Francesca gave birth to a daughter in the summer of 1725, her participation in the upcoming season was in question. The Royal Academy had to prepare a replacement. Handel himself goes to Vienna, to the court of Emperor Charles VI. Here they idolize another Italian – Faustina Bordoni. The composer, acting as an impresario, manages to conclude a contract with the singer, offering good financial conditions.

“Having acquired a new“ diamond ”in the person of Bordoni, Handel also received new problems,” notes E. Tsodokov. – How to combine two prima donnas on stage? After all, Cuzzoni’s morals are known, and the public, divided into two camps, will add fuel to the fire. All this is foreseen by the composer, writing his new opera “Alexander”, where Francesca and Faustina (for which this is also a London debut) are supposed to converge on the stage. For future rivals, two equivalent roles are intended – the wives of Alexander the Great, Lizaura and Roxana. Moreover, the number of arias should be equal, in duets they should solo alternately. And God forbid that the balance was broken! Now it becomes clear what tasks, far from music, Handel often had to solve in his operatic work. This is not the place to delve into the analysis of the musical heritage of the great composer, but, apparently, the opinion of those musicologists who believe that, having freed himself from the heavy opera “burden” in 1741, he gained that inner freedom that allowed him to create his own late masterpieces in the oratorio genre (“Messiah”, “Samson”, “Judas Maccabee”, etc.).

On May 5, 1726, the premiere of “Alexander” took place, which was a great success. In the first month alone, this production ran for fourteen performances. Senesino played the title role. The prima donnas are also at the top of their game. In all likelihood, it was the most outstanding opera ensemble of that time. Unfortunately, the British formed two camps of irreconcilable fans of prima donnas, which Handel so feared.

Composer I.-I. Quantz was a witness to that conflict. “Between the parts of both singers, Cuzzoni and Faustina, there was such a great enmity that when the fans of one began to applaud, the admirers of the other invariably whistled, in connection with which London stopped staging operas for some time. These singers had virtues so varied and striking that, had the regulars of musical performances not been enemies of their own pleasures, they might have applauded each one in turn, and in turn enjoyed their various perfections. To the misfortune of even-tempered people who seek pleasure in talent wherever they may be found, the fury of this feud has cured all subsequent entrepreneurs of the folly of bringing on two singers of the same sex and talent at the same time to cause controversy.

Here is what E. Tsodokov writes:

“During the year, the struggle did not go beyond the bounds of decency. The singers continued to perform successfully. But the next season began with great difficulties. First, Senesino, who was tired of being in the shadow of the rivalry of prima donnas, said he was sick and left for the continent (returned for the next season). Secondly, the unthinkable fees of the stars shook the financial situation of the Academy’s management. They did not find anything better than to “renew” the rivalry between Handel and Bononcini. Handel writes a new opera “Admet, King of Thessaly”, which was a significant success (19 performances per season). Bononcini is also preparing a new premiere – the opera Astianax. It was this production that became fatal in the rivalry between the two stars. If before that the struggle between them was carried out mainly by the “hands” of fans and boiled down to mutual booing at performances, “watering” each other in the press, then at the premiere of Bononcini’s new work, it went into a “physical” stage.

Let us describe in more detail this scandalous premiere, which took place on June 6, 1727, in the presence of the wife of the Prince of Wales Caroline, where Bordoni sang the part of Hermione, and Cuzzoni sang Andromache. After the traditional booing, the parties moved on to the “cat concert” and other obscene things; the nerves of the prima donnas could not stand it, they clung to each other. A uniform female fight began – with scratching, squealing, pulling hair. The bloody tigresses beat each other for nothing. The scandal was so great that it led to the closing of the opera season.”

The director of the Drury Lane Theatre, Colley Syber, staged a farce the following month in which the two singers were brought out ruffling each other’s chignons, and Handel phlegmatically saying to those who wanted to separate them: “Leave it. When they get tired, their rage will go away on its own.” And, in order to hasten the end of the battle, he encouraged him with loud beats of the timpani.

This scandal was also one of the reasons for the creation of the famous “Opera of the Beggars” by D. Gay and I.-K. Pepusha in 1728. The conflict between the prima donnas is shown in the famous bickering duet between Polly and Lucy.

Pretty soon the conflict between the singers faded away. The famous trio again performed together in Handel’s operas Cyrus, King of Persia, Ptolemy, King of Egypt. But all this does not save the “Kingstier”, the theater’s affairs are constantly deteriorating. Without waiting for the collapse, in 1728 both Cuzzoni and Bordoni left London.

Cuzzoni continues his performances at home in Venice. Following this, she appears in Vienna. In the capital of Austria, she did not stay long due to large financial requests. In 1734-1737, Cuzzoni sang again in London, this time with the troupe of the famous composer Nicola Porpora.

Returning to Italy in 1737, the singer performed in Florence. Since 1739 she has been touring Europe. Cuzzoni performs in Vienna, Hamburg, Stuttgart, Amsterdam.

There are still a lot of rumors around the prima donna. It is even rumored that she killed her own husband. In Holland, Cuzzoni ends up in a debtor’s prison. The singer is released from it only in the evenings. The fee from performances in the theater goes to pay off debts.

Cuzzoni-Sandoni died in poverty in Bologna in 1770, earning money in recent years by making buttons.