Fantasy |

from the Greek pantaoia – imagination; lat. and ital. fantasia, German Fantasia, French fantaisie, eng. fancy, fansy, phancy, fantasy

1) A genre of instrumental (occasionally vocal) music, the individual features of which are expressed in deviation from the norms of construction common for their time, less often in an unusual figurative content of traditions. composition scheme. Ideas about F. were different in different musical and historical. era, but at all times the boundaries of the genre remained fuzzy: in the 16-17 centuries. F. merges with ricercar, toccata, in the 2nd floor. 18th century – with a sonata, in the 19th century. – with a poem, etc. Ph. is always associated with the genres and forms common at a given time. At the same time, the work called F. is an unusual combination of “terms” (structural, meaningful) that are usual for this era. The degree of distribution and freedom of the F. genre depend on the development of the muses. forms in a given era: periods of an ordered, in one way or another strict style (16th – early 17th centuries, baroque art of the 1st half of the 18th century), marked by a “luxurious flowering” of F.; on the contrary, the loosening of established “solid” forms (romanticism) and especially the emergence of new forms (the 20th century) are accompanied by a reduction in the number of philosophies and an increase in their structural organization. The evolution of the genre of F. is inseparable from the development of instrumentalism as a whole: the periodization of the history of F. coincides with the general periodization of Western European. music lawsuit. F. is one of the oldest genres of instr. music, but, unlike most early instr. genres that have developed in connection with the poetic. speech and dance. movements (canzona, suite), F. is based on proper music. patterns. The emergence of F. refers to the beginning. 16th century One of its origins was improvisation. B. h. early F. intended for plucked instruments: numerous. F. for the lute and vihuela were created in Italy (F. da Milano, 1547), Spain (L. Milan, 1535; M. de Fuenllana, 1554), Germany (S. Kargel), France (A. Rippe), England ( T. Morley). F. for clavier and organ were much less common (F. in Organ Tablature by X. Kotter, Fantasia allegre by A. Gabrieli). Usually they are distinguished by contrapuntal, often consistently imitative. presentation; these F. are so close to capriccio, toccata, tiento, canzone that it is not always possible to determine why the play is called exactly F. (for example, the F. given below resembles richercar). The name in this case is explained by the custom to call F. an improvised or freely constructed ricercar (arrangements of vocal motets, varied in the instr. spirit, were also called).

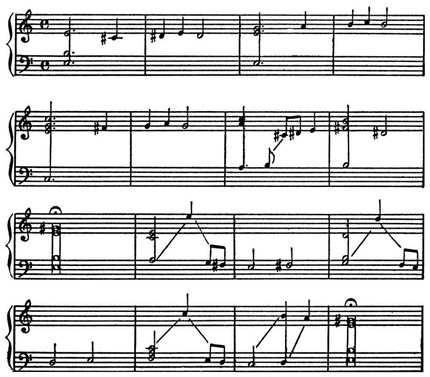

F. da Milano. Fantasy for lutes.

In the 16th century F. is also not uncommon, in which free handling of voices (associated, in particular, with the peculiarities of voice leading on plucked instruments) actually leads to a chord warehouse with a passage-like presentation.

L. Milan. Fantasy for vihuela.

In the 17th century F. becomes very popular in England. G. Purcell addresses her (for example, “Fantasy for one sound”); J. Bull, W. Bird, O. Gibbons, and other virginalists bring F. closer to the traditional. English form – ground (it is significant that the variant of its name – fancy – coincides with one of the names of F.). The heyday of F. in the 17th century. associated with org. music. F. at J. Frescobaldi are an example of ardent, temperamental improvisation; The “chromatic fantasy” of the Amsterdam master J. Sweelinck (combines the features of a simple and complex fugue, ricercar, polyphonic variations) testifies to the birth of a monumental instrument. style; S. Scheidt worked in the same tradition, to-ry called F. contrapuntal. chorale arrangements and choral variations. The work of these organists and harpsichordists prepared the great achievements of J. S. Bach. At this time, the attitude to F. was determined as to the work of an upbeat, excited or dramatic. character with the typical freedom of alternation and development or the quirkiness of the changes of muses. images; becomes almost obligatory improvisation. an element that creates the impression of direct expression, the predominance of a spontaneous play of the imagination over a deliberate compositional plan. In the organ and clavier works of Bach, F. is the most pathetic and most romantic. genre. F. in Bach (as in D. Buxtehude and G. F. Telemann, who uses the da capo principle in F.) or is combined in a cycle with a fugue, where, like a toccata or prelude, it serves to prepare and shade the next piece (F. and fugue for organ g-moll, BWV 542), or used as an intro. parts in a suite (for violin and clavier A-dur, BWV 1025), partita (for clavier a-minor, BWV 827), or, finally, exists as independent. prod. (F. for organ G-dur BWV 572). In Bach, the rigor of organization does not contradict the principle of free F. For example, in Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue, freedom of presentation is expressed in a bold combination of different genre features – org. improvisation texture, recitative and figurative processing of the chorale. All sections are held together by the logic of the movement of keys from T to D, followed by a stop at S and a return to T (thus, the principle of the old two-part form is extended to F.). A similar picture is also characteristic of Bach’s other fantasies; although they are often saturated with imitations, the main shaping force in them is harmony. Ladoharmonic. the frame of the form can be revealed through giant org. points that support the tonics of the leading keys.

A special variety of Bach’s F. are certain choral arrangements (for example, “Fantasia super: Komm, heiliger Geist, Herre Gott”, BWV 651), the principles of development in which do not violate the traditions of the choral genre. An extremely free interpretation distinguishes the improvisational, often out-of-tact fantasies of F. E. Bach. According to his statements (in the book “Experience of the correct way of playing the clavier”, 1753-62), “fantasy is called free when more keys are involved in it than in a piece composed or improvised in strict meter … Free fantasy contains various harmonic passages which can be played in broken chords or all sorts of different figurations… The tactless free fantasy is great for expressing emotions.”

Confused lyric. fantasies of W. A. Mozart (clavier F. d-moll, K.-V. 397) testify to the romantic. interpretation of the genre. In the new conditions they fulfill their long-standing function. pieces (but not to the fugue, but to the sonata: F. and sonata c-moll, K.-V. 475, 457), recreate the principle of alternating homophonic and polyphonic. presentations (org. F. f-moll, K.-V. 608; scheme: A B A1 C A2 B1 A3, where B are fugue sections, C are variations). I. Haydn introduced F. to the quartet (op. 76 No 6, part 2). L. Beethoven consolidated the union of the sonata and F. by creating the famous 14th sonata, op. 27 No 2 – “Sonata quasi una Fantasia” and the 13th sonata op. 27 No 1. He brought to F. the idea of symphony. development, virtuoso qualities instr. concerto, the monumentality of the oratorio: in F. for piano, choir and orchestra c-moll op. 80 as a hymn to the arts sounded (in the C-dur central part, written in the form of variations) the theme, later used as the “theme of joy” in the finale of the 9th symphony.

Romantics, for example. F. Schubert (series of F. for pianoforte in 2 and 4 hands, F. for violin and pianoforte op. 159), F. Mendelssohn (F. for pianoforte op. 28), F. Liszt (org. and pianoforte . F.) and others, enriched F. with many typical qualities, deepening the features of programmaticity that were previously manifested in this genre (R. Schumann, F. for piano C-dur op. 17). It is significant, however, that “romantic. freedom”, characteristic of the forms of the 19th century, to the least extent concerns F. It uses common forms – sonata (A. N. Skryabin, F. for piano in h-moll op. 28; S. Frank, org. F. A-dur), sonata cycle (Schumann, F. for piano C-dur op. 17). In general, for F. 19th century. characteristic, on the one hand, is the fusion with free and mixed forms (including poems), and on the other, with rhapsodies. Mn. compositions that do not bear the name F., in essence, are them (S. Frank, “Prelude, Chorale and Fugue”, “Prelude, Aria and Finale”). Rus. composers introduce F. into the sphere of the wok. (M. I. Glinka, “Venetian Night”, “Night Review”) and symphony. music: in their work there was a specific. orc. a variety of the genre is the symphonic fantasy (S. V. Rachmaninov, The Cliff, op. 7; A. K. Glazunov, The Forest, op. 19, The Sea, op. 28, etc.). They give F. something distinctly Russian. character (M. P. Mussorgsky, “Night on Bald Mountain”, the form of which, according to the author, is “Russian and original”), then the favorite oriental (M. A. Balakirev, eastern F. “Islamey” for fp. ), then fantastic (A. S. Dargomyzhsky, “Baba Yaga” for orchestra) coloring; give it philosophically significant plots (P. I. Tchaikovsky, “The Tempest”, F. for orchestra based on the drama of the same name by W. Shakespeare, op. 18; “Francesca da Rimini”, F. for orchestra on the plot of the 1st song of Hell from “Divine Comedy” by Dante, op.32).

In the 20th century F. as independent. the genre is rare (M. Reger, Choral F. for organ; O. Respighi, F. for piano and orchestra, 1907; J. F. Malipiero, Every Day’s Fantasy for orchestra, 1951; O. Messiaen, F. for violin and piano; M. Tedesco, F. for 6-string guitar and piano; A. Copland, F. for piano; A. Hovaness, F. from Suite for piano “Shalimar”; N (I. Peiko, Concert F. for horn and chamber orchestra, etc.). Sometimes neoclassical tendencies are manifested in F. (F. Busoni, “Counterpoint F.”; P. Hindemith, sonatas for viola and piano – in F, 1st part, in S., 3rd part; K. Karaev, sonata for violin and piano, finale, J. Yuzeliunas, concerto for organ, 1st movement). In a number of cases, new compositions are used in F. means of the 20th century – dodecaphony (A. Schoenberg, F. for violin and piano; F. Fortner, F. on the theme “BACH” for 2 pianos, 9 solo instruments and orchestra), sonor-aleatoric. techniques (S. M. Slonimsky, “Coloristic F.” for piano).

In the 2nd floor. 20th century one of the important genre features of philosophicism—the creation of an individual, improvisationally direct (often with a tendency to develop through) form—is characteristic of music of any genre, and in this sense, many of the latest compositions (for example, the 4th and 5th pianos sonatas by B. I. Tishchenko) merge with F.

2) Auxiliary. a definition indicating a certain freedom of interpretation decomp. genres: waltz-F. (M.I. Glinka), Impromptu-F., Polonaise-F. (F. Chopin, op. 66,61), sonata-F. (A. N. Scriabin, op. 19), overture-F. (P. I. Tchaikovsky, “Romeo and Juliet”), F. Quartet (B. Britten, “Fantasy quartet” for oboe and strings. trio), recitative-F. (S. Frank, sonata for violin and piano, part 3), F.-burlesque (O. Messiaen), etc.

3) Common in the 19-20 centuries. genre instr. or orc. music, based on the free use of themes borrowed from their own compositions or from the works of other composers, as well as from folklore (or written in the nature of folk). Depending on the degree of creativity. reworking the themes of F. either forms a new artistic whole and then approaches paraphrase, rhapsody (many fantasies of Liszt, “Serbian F.” for Rimsky-Korsakov’s orchestra, “F. on Ryabinin’s themes” for piano with Arensky’s orchestra, “Cinematic F. .” on the themes of the musical farce “The Bull on the Roof” for violin and orchestra Milhaud, etc.), or is a simple “montage” of themes and passages, similar to a potpourri (F. on the themes of classical operettas, F. on the themes of popular songs composers, etc.).

4) Creative fantasy (German Phantasie, Fantasie) – the ability of human consciousness to represent (internal vision, hearing) the phenomena of reality, the appearance of which is historically determined by societies. experience and activities of mankind, and to the mental creation by combining and processing these ideas (at all levels of the psyche, including the rational and subconscious) of art. images. Accepted in owls. science (psychology, aesthetics) understanding of the nature of creativity. F. is based on the Marxist position on the historical. and societies. conditionality of human consciousness and on the Leninist theory of reflection. In the 20th century there are other views on the nature of creativity. F., which are reflected in the teachings of Z. Freud, C. G. Jung and G. Marcuse.

References: 1) Kuznetsov K. A., Musical and historical portraits, M., 1937; Mazel L., Fantasia f-moll Chopin. The experience of analysis, M., 1937, the same, in his book: Research on Chopin, M., 1971; Berkov V. O., Chromatic fantasy J. Sweelinka. From the history of harmony, M., 1972; Miksheeva G., Symphonic fantasies of A. Dargomyzhsky, in the book: From the history of Russian and Soviet music, vol. 3, M., 1978; Protopopov V.V., Essays from the history of instrumental forms of the 1979th – early XNUMXth centuries, M., XNUMX.

3) Marx K. and Engels R., On Art, vol. 1, M., 1976; Lenin V. I., Materialism and empirio-criticism, Poln. coll. soch., 5th ed., v. 18; his own, Philosophical Notebooks, ibid., vol. 29; Ferster N. P., Creative fantasy, M., 1924; Vygotsky L. S., Psychology of art, M., 1965, 1968; Averintsev S. S., “Analytical Psychology” K.-G. Jung and patterns of creative fantasy, in: On Modern Bourgeois Aesthetics, vol. 3, M., 1972; Davydov Yu., Marxist historicism and the problem of the crisis of art, in collection: Modern bourgeois art, M., 1975; his, Art in the social philosophy of G. Marcuse, in: Critique of modern bourgeois sociology of art, M., 1978.

TS Kyuregyan