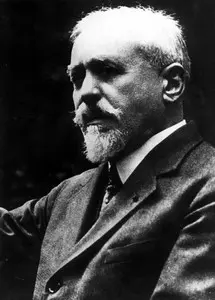

Christoph Willibald Gluck |

Christopher Willibald Gluck

K. V. Gluck is a great opera composer who carried out in the second half of the XNUMXth century. reform of the Italian opera-seria and the French lyrical tragedy. The great mythological opera, which was going through an acute crisis, acquired in Gluck’s work the qualities of a genuine musical tragedy, filled with strong passions, elevating the ethical ideals of fidelity, duty, readiness for self-sacrifice. The appearance of the first reformist opera “Orpheus” was preceded by a long way – the struggle for the right to become a musician, wandering, mastering various opera genres of that time. Gluck lived an amazing life, devoting himself entirely to musical theater.

Gluck was born into a forester’s family. The father considered the profession of a musician an unworthy occupation and in every possible way interfered with the musical hobbies of his eldest son. Therefore, as a teenager, Gluck leaves home, wanders, dreams of getting a good education (by this time he had graduated from the Jesuit college in Kommotau). In 1731 Gluck entered the University of Prague. A student of the Faculty of Philosophy devoted a lot of time to musical studies – he took lessons from the famous Czech composer Boguslav Chernogorsky, sang in the choir of St. Jacob’s Church. Wanderings in the environs of Prague (Gluk willingly played the violin and especially his beloved cello in wandering ensembles) helped him to become more familiar with Czech folk music.

In 1735, Gluck, already an established professional musician, traveled to Vienna and entered the service of Count Lobkowitz’s choir. Soon the Italian philanthropist A. Melzi offered Gluck a job as a chamber musician in the court chapel in Milan. In Italy, Gluck’s path as an opera composer begins; he gets acquainted with the work of the largest Italian masters, is engaged in composition under the direction of G. Sammartini. The preparatory stage continued for almost 5 years; it was not until December 1741 that Gluck’s first opera Artaxerxes (libre P. Metastasio) was successfully staged in Milan. Gluck receives numerous orders from the theaters of Venice, Turin, Milan, and within four years creates several more opera seria (“Demetrius”, “Poro”, “Demofont”, “Hypermnestra”, etc.), which brought him fame and recognition from rather sophisticated and demanding Italian public.

In 1745 the composer toured London. The oratorios of G. F. Handel made a strong impression on him. This sublime, monumental, heroic art became for Gluck the most important creative reference point. A stay in England, as well as performances with the Italian opera troupe of the Mingotti brothers in the largest European capitals (Dresden, Vienna, Prague, Copenhagen) enriched the composer’s musical experience, helped to establish interesting creative contacts, and get to know various opera schools better. Gluck’s authority in the music world was recognized by his awarding the papal Order of the Golden Spur. “Cavalier Glitch” – this title was assigned to the composer. (Let us recall the wonderful short story by T. A. Hoffmann “Cavalier Gluck”.)

A new stage in the life and work of the composer begins with a move to Vienna (1752), where Gluck soon took the post of conductor and composer of the court opera, and in 1774 received the title of “actual imperial and royal court composer.” Continuing to compose seria operas, Gluck also turned to new genres. French comic operas (Merlin’s Island, The Imaginary Slave, The Corrected Drunkard, The Fooled Cady, etc.), written to the texts of the famous French playwrights A. Lesage, C. Favard and J. Seden, enriched the composer’s style with new intonations, compositional techniques, responded to the needs of listeners in a directly vital, democratic art. Gluck’s work in the ballet genre is of great interest. In collaboration with the talented Viennese choreographer G. Angiolini, the pantomime ballet Don Giovanni was created. The novelty of this performance – a genuine choreographic drama – is largely determined by the nature of the plot: not traditionally fabulous, allegorical, but deeply tragic, sharply conflicting, affecting the eternal problems of human existence. (The script of the ballet was written based on the play by J. B. Molière.)

The most important event in the composer’s creative evolution and in the musical life of Vienna was the premiere of the first reformist opera, Orpheus (1762). strict and sublime ancient drama. The beauty of Orpheus’s art and the power of his love are able to overcome all obstacles – this eternal and always exciting idea lies at the heart of the opera, one of the most perfect creations of the composer. In the arias of Orpheus, in the famous flute solo, also known in numerous instrumental versions under the name “Melody”, the composer’s original melodic gift was revealed; and the scene at the gates of Hades – the dramatic duel between Orpheus and the Furies – has remained a remarkable example of the construction of a major operatic form, in which absolute unity of musical and stage development has been achieved.

Orpheus was followed by 2 more reformist operas – Alcesta (1767) and Paris and Helena (1770) (both in libre. Calcabidgi). In the preface to “Alceste”, written on the occasion of the dedication of the opera to the Duke of Tuscany, Gluck formulated the artistic principles that guided all his creative activity. Not finding proper support from the Viennese and Italian public. Gluck goes to Paris. The years spent in the capital of France (1773-79) are the time of the composer’s highest creative activity. Gluck writes and stages new reformist operas at the Royal Academy of Music – Iphigenia at Aulis (libre by L. du Roulle after the tragedy by J. Racine, 1774), Armida (libre by F. Kino based on the poem Jerusalem Liberated by T. Tasso ”, 1777), “Iphigenia in Taurida” (libre. N. Gniyar and L. du Roulle based on the drama by G. de la Touche, 1779), “Echo and Narcissus” (libre. L. Chudi, 1779), reworks “Orpheus ” and “Alceste”, in accordance with the traditions of the French theater. Gluck’s activity stirred up the musical life of Paris and provoked the sharpest aesthetic discussions. On the side of the composer are the French enlighteners, encyclopedists (D. Diderot, J. Rousseau, J. d’Alembert, M. Grimm), who welcomed the birth of a truly lofty heroic style in opera; his opponents are adherents of the old French lyric tragedy and opera seria. In an effort to shake Gluck’s position, they invited the Italian composer N. Piccinni, who enjoyed European recognition at that time, to Paris. The controversy between the supporters of Gluck and Piccinni entered the history of French opera under the name “wars of Glucks and Piccinnis”. The composers themselves, who treated each other with sincere sympathy, remained far from these “aesthetic battles”.

In the last years of his life, spent in Vienna, Gluck dreamed of creating a German national opera based on the plot of F. Klopstock’s “Battle of Hermann”. However, serious illness and age prevented the implementation of this plan. During the funeral of Glucks in Vienna, his last work “De profundls” (“I call from the abyss …”) for choir and orchestra was performed. Gluck’s student A. Salieri conducted this original requiem.

G. Berlioz, a passionate admirer of his work, called Gluck “Aeschylus of Music”. The style of Gluck’s musical tragedies — sublime beauty and nobility of images, impeccable taste and unity of the whole, monumentality of the composition, based on the interaction of solo and choral forms — goes back to the traditions of ancient tragedy. Created in the heyday of the enlightenment movement on the eve of the French Revolution, they responded to the needs of the time in great heroic art. So, Diderot wrote shortly before Gluck’s arrival in Paris: “Let a genius appear who will establish a true tragedy … on the lyrical stage.” Having set as his goal “to expel from the opera all those bad excesses against which common sense and good taste have been protesting in vain for a long time,” Gluck creates a performance in which all components of dramaturgy are logically expedient and perform certain, necessary functions in the overall composition. “… I avoided demonstrating a heap of spectacular difficulties to the detriment of clarity,” says the Alceste dedication, “and I did not attach any value to the discovery of a new technique if it did not follow naturally from the situation and was not associated with expressiveness.” Thus, the choir and ballet become full participants in the action; intonationally expressive recitatives naturally merge with arias, the melody of which is free from the excesses of a virtuoso style; the overture anticipates the emotional structure of the future action; relatively complete musical numbers are combined into large scenes, etc. Directed selection and concentration of means of musical and dramatic characterization, strict subordination of all links of a large composition – these are Gluck’s most important discoveries, which were of great importance both for updating operatic dramaturgy and for establishing a new one, symphonic thinking. (The heyday of Gluck’s operatic creativity falls on the time of the most intensive development of large cyclic forms – the symphony, sonata, concept.) An older contemporary of I. Haydn and W. A. Mozart, closely connected with the musical life and artistic atmosphere of Vienna. Gluck, and in terms of the warehouse of his creative individuality, and in terms of the general orientation of his searches, adjoins precisely the Viennese classical school. The traditions of Gluck’s “high tragedy”, the new principles of his dramaturgy were developed in the opera art of the XNUMXth century: in the works of L. Cherubini, L. Beethoven, G. Berlioz and R. Wagner; and in Russian music – M. Glinka, who highly valued Gluck as the first opera composer of the XNUMXth century.

I. Okhalova

The son of a hereditary forester, from an early age accompanies his father in his many journeys. In 1731 he entered the University of Prague, where he studied vocal art and playing various instruments. Being in the service of Prince Melzi, he lives in Milan, takes composition lessons from Sammartini and puts on a number of operas. In 1745, in London, he met Handel and Arne and composed for the theatre. Becoming the bandmaster of the Italian troupe Mingotti, he visits Hamburg, Dresden and other cities. In 1750 he marries Marianne Pergin, daughter of a wealthy Viennese banker; in 1754 he became bandmaster of the Vienna Court Opera and was part of the entourage of Count Durazzo, who managed the theater. In 1762, Gluck’s opera Orpheus and Eurydice was successfully staged to a libretto by Calzabidgi. In 1774, after several financial setbacks, he follows Marie Antoinette (to whom he was music teacher), who became the French queen, to Paris and wins the favor of the public despite the resistance of the piccinnists. However, upset by the failure of the opera “Echo and Narcissus” (1779), he leaves France and leaves for Vienna. In 1781, the composer was paralyzed and ceased all activities.

Gluck’s name is identified in the history of music with the so-called reform of the musical drama of the Italian type, the only one known and widespread in Europe in his time. He is considered not only a great musician, but above all the savior of a genre distorted in the first half of the XNUMXth century by the virtuosic decorations of the singers and the rules of conventional, machine-based librettos. Nowadays, Gluck’s position no longer seems exceptional, since the composer was not the only creator of the reform, the need for which was felt by other opera composers and librettists, in particular Italian ones. Moreover, the concept of the decline of the musical drama cannot apply to the pinnacle of the genre, but only to low-grade compositions and authors of little talent (it is difficult to blame such a master as Handel for the decline).

Be that as it may, prompted by the librettist Calzabigi and other members of the entourage of Count Giacomo Durazzo, manager of the Vienna imperial theaters, Gluck introduced a number of innovations into practice, which undoubtedly led to major results in the field of musical theater. Calcabidgi recalled: “It was impossible for Mr. Gluck, who spoke our language [that is, Italian], to recite poetry. I read Orpheus to him and several times recited many fragments, emphasizing the shades of recitation, stops, slowing down, speeding up, sounds now heavy, now smooth, which I wanted him to use in his composition. At the same time, I asked him to remove all fioritas, cadenzas, ritornellos, and all that barbaric and extravagant that had penetrated into our music.

Resolute and energetic by nature, Gluck undertook the implementation of the planned program and, relying on Calzabidgi’s libretto, declared it in the preface to Alceste, dedicated to the Grand Duke of Tuscany Pietro Leopoldo, the future Emperor Leopold II.

The main principles of this manifesto are as follows: to avoid vocal excesses, funny and boring, to make music serve poetry, to enhance the meaning of the overture, which should introduce listeners to the content of the opera, to soften the distinction between recitative and aria so as not to “interrupt and dampen the action.”

Clarity and simplicity should be the goal of the musician and poet, they should prefer “the language of the heart, strong passions, interesting situations” to cold moralization. These provisions now seem to us for granted, unchanged in the musical theater from Monteverdi to Puccini, but they were not so in the time of Gluck, to whose contemporaries “even small deviations from the accepted seemed a tremendous novelty” (in the words of Massimo Mila).

As a result, the most significant in the reform were the dramatic and musical achievements of Gluck, who appeared in all his greatness. These achievements include: penetration into the feelings of the characters, the classical majesty, especially of the choral pages, the depth of thought that distinguishes the famous arias. After parting with Calzabidgi, who, among other things, fell out of favor at court, Gluck found support in Paris for many years from French librettists. Here, despite fatal compromises with the local refined but inevitably superficial theater (at least from a reformist point of view), the composer nevertheless remained worthy of his own principles, especially in the operas Iphigenia in Aulis and Iphigenia in Tauris.

G. Marchesi (translated by E. Greceanii)

glitch. Melody (Sergei Rachmaninov)