Chords in music and their types

Contents

The topic of today’s publication is chords in music. We will talk about what a chord is and what types of chords there are.

A chord is a consonance of several sounds (from three or more) that are in relation to each other at a certain distance, that is, at some intervals. What is consonance? Consonance is sounds that coexist together. The simplest consonance is the interval, more complex types of consonances are various chords.

The term “consonance” can be compared with the word “constellation”. In the constellations, several stars are located at different distances from each other. If you connect them, you can get the outlines of figures of animals or mythological heroes. Similar in music, the combination of sounds gives consonances of certain chords.

What are the chords?

In order to get a chord, you need to combine at least three sounds or more. The type of chord depends on how many sounds are linked together, and on how they are connected (at what intervals).

In classical music, sounds in chords are arranged in thirds. A chord in which three sounds arranged in thirds is called a triad. If you record the triad with notes, then the graphic representation of this chord will very much resemble a small snowman.

If consonance is four sounds, also separated from each other by a third, then it turns out seventh chord. The name “seventh chord” means that between the extreme sounds of the chord, an interval of “septim” is formed. In the recording, the seventh chord is also a “snowman”, only not from three snowballs, but from four.

If the in a chord there are five connected sounds by thirdsthen it is called non-chord (according to the interval “nona” between its extreme points). Well, the musical notation of such a chord will give us a “snowman”, which, it seems, has eaten too many carrots, because it has grown to five snowballs!

Triad, seventh chord and nonchord are the main types of chords used in music. However, this series can be continued with other harmonies, which are formed according to the same principle, but are used much less frequently. These can include undecimacchord (6 sounds by thirds), tertsdecimacchord (7 sounds by thirds), quintdecimacchord (8 sounds by thirds). It is curious that if you build a third decimal chord or a fifth decimal chord from the note “do”, then they will include absolutely all seven steps of the musical scale (do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, si).

So, the main types of chords in music are as follows:

- A triad – a chord of three sounds arranged in thirds is indicated by a combination of numbers 5 and 3 (53);

- Seventh chord – a chord of four sounds in thirds, between the extreme sounds of the seventh, is indicated by the number 7;

- Nonaccord – a chord of five sounds in thirds, between the extreme sounds of non, is indicated by the number 9.

Non-tertz structure chords

In modern music, one can often find chords in which sounds are located not in thirds, but in other intervals – usually in fourths or fifths. For example, from the connection of two quarts, the so-called quarter-seventh chord is formed (indicated by a combination of the numbers 7 and 4) with a seventh between the extreme sounds.

From the clutch of two fifths, you can get quint-chords (indicated by the numbers 9 and 5), there will be a non-compound interval between the lower and upper sound.

Classical tertsovye chords sound soft, harmonious. The chords of the non-tertzian structure have an empty sound, but they are very colorful. This is probably why these chords are so appropriate where the creation of fantastically mysterious musical images is required.

As an example, let’s call Prelude “Sunken Cathedral” by French composer Claude Debussy. Empty chords of fifths and fourths here help to create an image of the movement of water and the appearance of the legendary cathedral invisible during the day, rising from the water surface of the lake only at night. The same chords seem to convey the ringing of bells and the midnight strike of the clock.

One more example – piano piece by another French composer Maurice Ravel “Gallows” from the cycle “Ghosts of the Night”. Here, heavy quint-chords are just the right way to paint a gloomy picture.

Clusters or second bunches

Until now, we have mentioned only those consonances that consist of consonances of various kinds – thirds, fourths and fifths. But consonances can also be built from intervals-dissonances, including from seconds.

So-called clusters are formed from seconds. They are sometimes also called second bunches. (their graphic image is very reminiscent of a bunch of some berries – for example, mountain ash or grapes).

Quite often clusters are indicated in music not in the form of “scatters of notes”, but as filled or empty rectangles located on the stave. They should be understood as follows: all notes are played (white or black piano keys depending on the color of the cluster, sometimes both) within the boundaries of this rectangle.

An example of such clusters can be seen in piano piece “Festive” by Russian composer Leyla Ismagilova.

Clusters are generally not classified as chords. The reason for that is the following. It turns out that in any chord, the individual sounds of its components should be well heard. Any such sound can be distinguished by hearing at any moment of the sound and, for example, sing the rest of the sounds that make up the chord, while we will not be disturbed. In clusters it is different, because all their sounds merge into a single colorful spot, and it is not possible to hear any of them separately.

Varieties of triads, seventh chords and nonchords

Classical chords have many varieties. There are only four types of triads, seventh chords – 16, but only 7 have been fixed in practice, there may be even more variants of non-chords (64), but those that are used constantly can again be counted on the fingers (4-5).

We will devote separate issues to a detailed examination of the types of triads and seventh chords in the future, but now we will give them only the briefest description.

But first, you need to understand why there are different types of chords at all? As we noted earlier, musical intervals act as the “building material” for chords. These are kind of bricks, from which the “building of the chord” is then obtained.

But you also remember that intervals also have many varieties, they can be wide or narrow, but also clean, large, small, reduced, etc. The shape of the interval-brick depends on its qualitative and quantitative value. And from what intervals we build (and you can build chords from intervals both the same and different), it depends on what kind of chord, in the end, we will get.

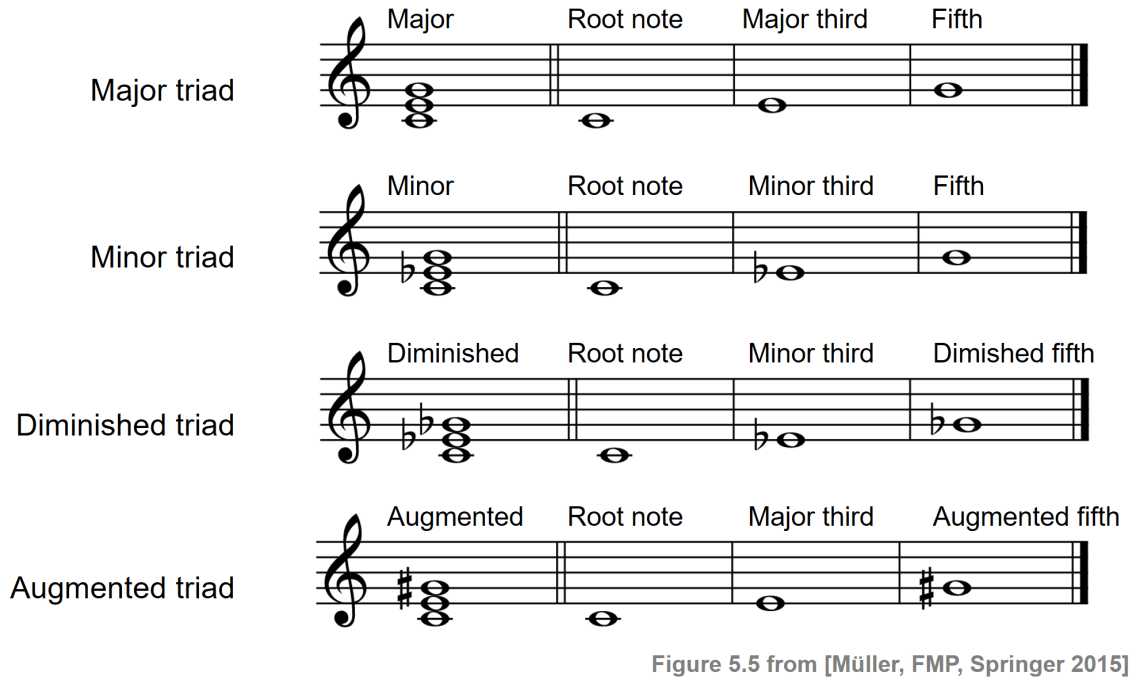

So, triad has 4 types. It can be major (or major), minor (or minor), diminished or augmented.

- Big (major) triad denoted by a capital letter B with the addition of the numbers 5 and 3 (B53). It consists of a major and a minor third, in exactly this order: first, a major third is below, and a minor is built on top of it.

- Small (minor) triad denoted by a capital letter M with the addition of the same numbers (M53). A small triad, on the contrary, begins with a small third, to which a large one is added on top.

- Augmented triad obtained by combining two major thirds, abbreviated as – Uv.53.

- Reduced triad is formed by joining two small thirds, its designation is Um.53.

In the following example, you can see all the listed types of triads built from the notes “mi” and “fa”:

There are seven main types of seventh chords. (7 out of 16). Their names are made up of two elements: the first is the type of seventh between the extreme sounds (it can be large, small, reduced or increased); the second is a type of triad, which is located at the base of the seventh chord (that is, a kind of triad, which is formed from the three lower sounds).

For example, the name “small major seventh chord” should be understood as follows: this seventh chord has a small seventh between the bass and the upper sound, and inside it there is a major triad.

So, the 7 main types of seventh chords can be easily remembered like this – three of them will be large, three – small, and one – reduced:

- Grand major seventh chord – major seventh + major triad at the base (B.mazh.7);

- Major minor seventh chord – major seventh at the edges + minor triad at the bottom (B.min.7);

- Grand augmented seventh chord – a major seventh between the extreme sounds + an increased triad form three lower sounds from the bass (B.uv.7);

- Small major seventh chord – small seventh along the edges + major triad in the base (M.mazh.7);

- Small minor seventh chord – a small seventh is formed by extreme sounds + a minor triad is obtained from the three lower tones (M. min. 7);

- Small diminished seventh chord – small seventh + triad inside diminished (M.um.7);

- Reduced seventh chord – the seventh between the bass and the upper sound is reduced + the triad inside is also reduced (Um.7).

The musical example demonstrates the listed types of seventh chords, built from the sounds “re” and “salt”:

As for non-chords, they must be learned to distinguish, mainly by their none. As a rule, non-chords are used only with a small or a large note. Inside a non-chord, of course, it is required to be able to distinguish between the type of seventh and the type of triad.

Among common nonchords include the following (five in total):

- Grand major nonchord – with a big nona, a big seventh and a major triad (B.mazh.9);

- Major minor nonchord – with a big nona, a big seventh and a minor triad (B.min.9);

- Big augmented nonchord – with a large non, a large seventh and an increased triad (B.uv.9);

- Small major nonchord – with a small non, a small seventh and a major triad (M.mazh.9);

- Small minor nonchord – with a small nona, a small seventh and a minor triad (M. min. 9).

In the following musical example, these non-chords are built from the sounds “do” and “re”:

Conversion – a way to get new chords

From the main chords used in music, that is, according to our classification – from triads, seventh chords and nonchords – you can get other chords by inversion. We have already talked about the inversion of intervals, when, as a result of rearranging their sounds, new intervals are obtained. The same principle applies to chords. Chord inversions are performed, mainly, by moving the lower sound (bass) an octave higher.

So, triad can be reversed twice, in the course of appeals, we will receive new consonances – sextant and quartz sextant. Sixth chords are indicated by the number 6, quarter-sext chords – by two numbers (6 and 4).

For example, let’s take a triad from the sounds “d-fa-la” and make its inversion. We transfer the sound “re” an octave higher and get the consonance “fa-la-re” – this is the sixth chord of this triad. Next, let’s now move the sound “fa” up, we get “la-re-fa” – the quadrant-sextakcord of the triad. If we then move the sound “la” an octave higher, then we will again return to what we left – to the original triad “d-fa-la”. Thus, we are convinced that the triad really has only two inversions.

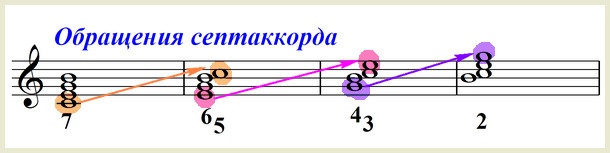

Seventh chords have three appeals – quintsextachord, third quarter chord and second chord, the principle of their implementation is the same. To designate fifth-sext chords, the combination of numbers 6 and 5 is used, for third quarter chords – 4 and 3, second chords are indicated by the number 2.

For example, given the seventh chord “do-mi-sol-si”. Let’s perform all its possible inversions and get the following: quintsextakkord “mi-sol-si-do”, third quarter chord “sol-si-do-mi”, second chord “si-do-mi-sol”.

Inversions of triads and seventh chords are used very often in music. But the inversions of non-chords or chords, in which there are even more sounds, are used extremely rarely (almost never), so we will not consider them here, although it is not difficult to get them and give them a name (all according to the same principle of bass transfer).

Two properties of a chord – structure and function

Any chord can be considered in two ways. First, you can build it from the sound and consider it structurally, that is, according to the interval composition. This structural principle is precisely reflected in the unique name of the chord – major triad, major minor seventh chord, minor fourth chord, etc.

By the name, we understand how we can build this or that chord from a given sound and what will be the “internal content” of this chord. And, mind you, nothing prevents us from building any chord from any sound.

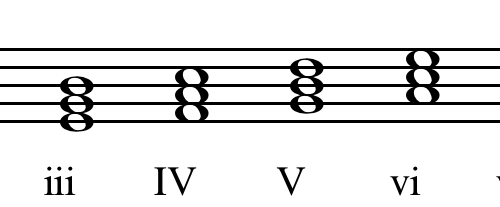

Secondly, chords can be considered on the steps of a major or minor scale. In this case, the formation of chords is greatly influenced by the type of mode, the signs of keys.

So, for example, in a major mode (let it be C major), major triads are obtained only on three steps – the first, fourth and fifth. On the remaining steps, it is possible to build only minor or diminished triads.

Similarly, in a minor (for example, let’s take C minor) – minor triads will also be only on the first, fourth and fifth steps, on the rest it will be possible to get either major or diminished.

The fact that only certain types of chords can be obtained on the degrees of major or minor, and not any (without restrictions) is the first feature of the “life” of chords in terms of fret.

Another feature is that chords acquire a function (that is, a certain role, meaning) and one more additional designation. It all depends on what degree the chord is built on. For example, triads and seventh chords built on the first step will be called triads or seventh chords of the first step or tonic triads (tonic seventh chords), as they will represent “tonic forces”, that is, they will refer to the first step.

Triads and seventh chords built on the fifth step, which is called the dominant, will be called dominant (dominant triad, dominant seventh chord). At the fourth step, subdominant triads and seventh chords are built.

This second property of chords, that is, the ability to perform some function, can be compared with the role of a player in some sports team, for example, in a football team. All athletes in the team are football players, but some are goalkeepers, others are defenders or midfielders, and still others are attackers, and each performs only his own, strictly defined task.

Chord functions should not be confused with structural names. For example, the dominant seventh chord in harmony in its structure is a small major seventh chord, and the seventh chord of the second step is a small minor seventh chord. But this does not mean at all that any small major seventh chord can be equated with a dominant seventh chord. And this also does not mean that some other chord in structure cannot act as a dominant seventh chord – for example, a small minor or a large increased.

So, in today’s issue, we have considered the main types of complex musical consonances – chords and clusters, touched upon the issues of their classification (chords with terts and non-terts structure), described the inversions and identified two main sides of the chord – structural and functional. In the next issues we will continue to study chords, take a closer look at the types of triads and seventh chords, as well as their most basic manifestations in harmony. Stay tuned!

Musical pause! At the piano – Denis Matsuev.

Jean Sibelius – Etude in A minor Op. 76 no. 2.