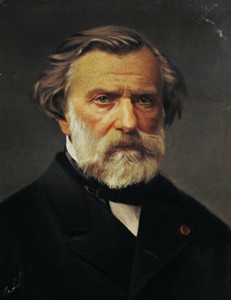

Charles Ives |

Charles Ives

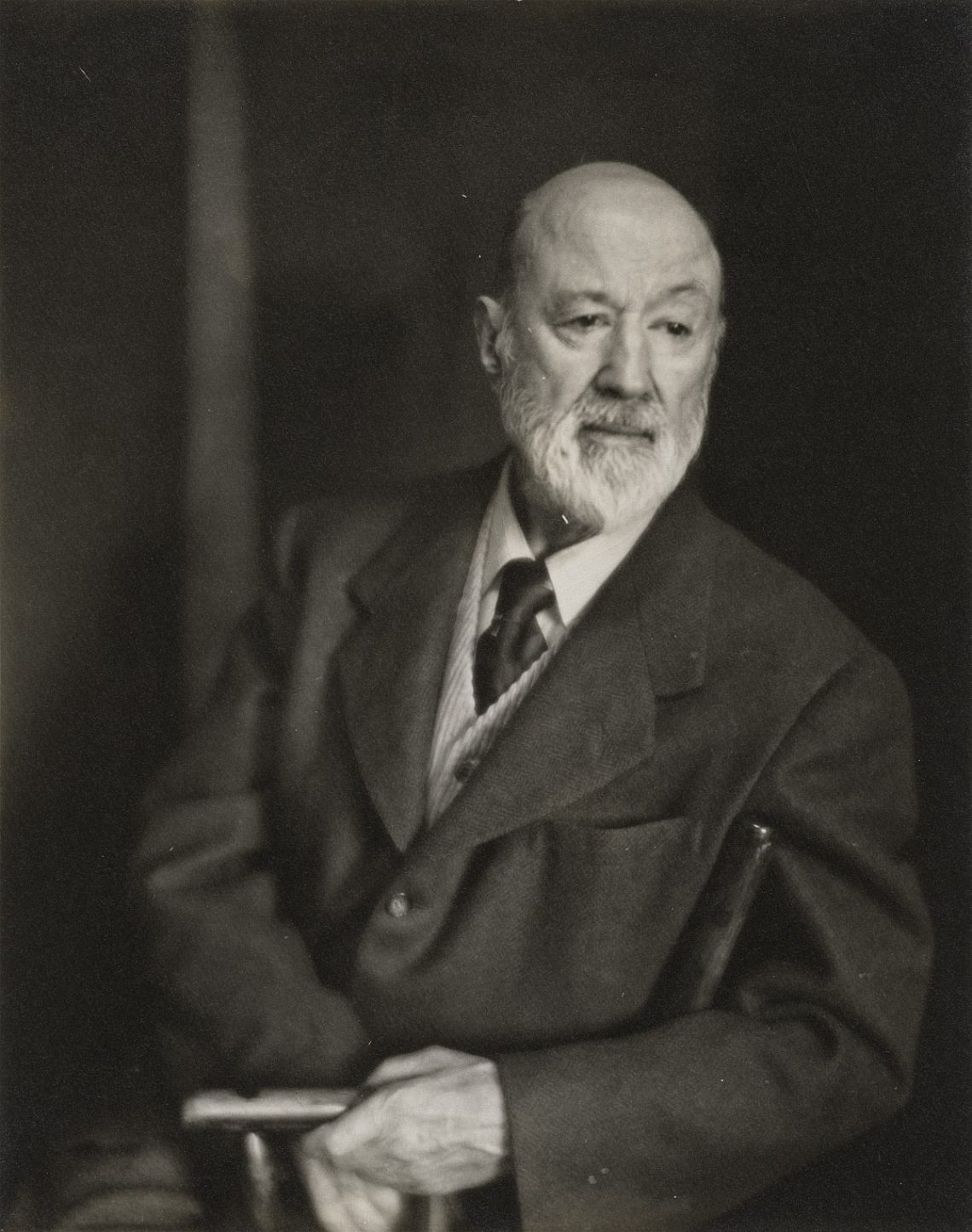

Probably, if the musicians of the early XX century. and on the eve of the First World War, they learned that the composer C. Ives lives in America and heard his works, they would have treated them as a kind of experiment, a curiosity, or they would not have noticed at all: he himself and that soil on which he has grown. But then no one knew Ives – for a very long time he did nothing at all to promote his music. Ives’ “discovery” took place only at the end of the 30s, when it turned out that many (and, moreover, very different) methods of the newest musical writing had already been tested by an original American composer in the era of A. Scriabin, C. Debussy and G. Mahler. By the time Ives became famous, he had not composed music for many years and, seriously ill, cut off contact with the outside world. “An American tragedy” called the fate of Ives one of his contemporaries. Ives was born into the family of a military conductor. His father was a tireless experimenter – this trait passed to his son, (For example, he instructed two orchestras going towards each other to play different works.) the “openness” of his work, which absorbed, probably, everything that sounded around. In many of his compositions, echoes of Puritan religious hymns, jazz, minstrel theater sound. As a child, Charles was brought up on the music of two composers – J. S. Bach and S. Foster (a friend of Ives’s father, an American “bard”, author of popular songs and ballads). Serious, alien to any vanity attitude to music, sublime structure of thoughts and feelings, Ives will later resemble Bach.

Ives wrote his first works for a military band (he played percussion instruments in it), at the age of 14 he became a church organist in his hometown. But he also played the piano in the theater, improvising ragtime and other pieces. After graduating from Yale University (1894-1898), where he studied with X. Parker (composition) and D. Buck (organ), Ives works as a church organist in New York. Then for many years he served as a clerk in an insurance company and did it with great passion. Subsequently, in the 20s, moving away from music, Ives became a successful businessman and a prominent specialist (author of popular works) on insurance. Most of Ives’s works belong to the genres of orchestral and chamber music. He is the author of five symphonies, overtures, program works for orchestra (Three Villages in New England, Central Park in the Dark), two string quartets, five sonatas for violin, two for pianoforte, pieces for organ, choirs and more than 100 songs. Ives wrote most of his major works for a long time, over several years. In the Second Piano Sonata (1911-15), the composer paid tribute to his spiritual predecessors. Each of its parts depicts a portrait of one of the American philosophers: R. Emerson, N. Hawthorne, G. Topo; the entire sonata bears the name of the place where these philosophers lived (Concord, Massachusetts, 1840-1860). Their ideas formed the basis of Ives’ worldview (for example, the idea of merging human life with the life of nature). Ives’ art is characterized by a high ethical attitude, his findings were never purely formal, but were a serious attempt to reveal the hidden possibilities inherent in the very nature of sound.

Before other composers, Ives came to many of the modern means of expression. From his father’s experiments with different orchestras, there is a direct path to polytonality (simultaneous sounding of several keys), surround, “stereoscopic” sound and aleatorics (when the musical text is not rigidly fixed, but arises from a combination of elements every time anew, as if by chance). Ives’ last major project (the unfinished “World” symphony) involved the arrangement of orchestras and the choir in the open air, in the mountains, at different points in space. Two parts of the symphony (Music of the Earth and Music of the Sky) had to sound … simultaneously, but twice, so that the listeners could alternately fix their attention on each. In some works, Ives approached the serial organization of atonal music earlier than A. Schoenberg.

The desire to penetrate into the bowels of sound matter led Ives to a quarter-tone system, completely unknown to classical music. He writes Three Quarter Tone Pieces for Two Pianos (appropriately tuned) and an article “Quarter Tone Impressions”.

Ives devoted more than 30 years to composing music, and only in 1922 published a number of works at his own expense. For the last 20 years of his life, Ives has retired from all business, which is facilitated by increasing blindness, heart disease and nervous system. In 1944, in honor of Ives’ 70th birthday, a jubilee concert was organized in Los Angeles. His music was highly appreciated by the largest musicians of our century. I. Stravinsky once noted: “Ives’ music told me more than novelists describing the American West … I discovered a new understanding of America in it.”

K. Zenkin