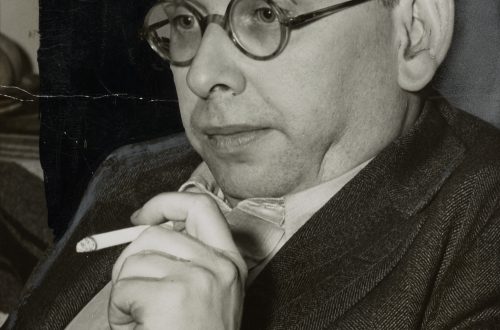

Boris Tischenko |

Boris Tischenko

The highest good … is nothing other than the knowledge of truth from its first causes. R. Descartes

B. Tishchenko is one of the prominent Soviet composers of the post-war generation. He is the author of the famous ballets “Yaroslavna”, “The Twelve”; stage works based on the words of K. Chukovsky: “The Fly-Sokotukha”, “The Stolen Sun”, “Cockroach”. The composer wrote a large number of large orchestral works – 5 non-programmed symphonies (including on the station by M. Tsvetaeva), “Sinfonia robusta”, the symphony “Chronicle of the Siege”; concertos for piano, cello, violin, harp; 5 string quartets; 8 piano sonatas (including the Seventh – with bells); 2 violin sonatas, etc. Tishchenko’s vocal music includes Five songs on st. O. Driz; Requiem for soprano, tenor and orchestra on st. A. Akhmatova; “Testament” for soprano, harp and organ at st. N. Zabolotsky; Cantata “Garden of Music” on st. A. Kushner. He orchestrated “Four Poems of Captain Lebyadkin” by D. Shostakovich. The composer’s Peru also includes music for the films “Suzdal”, “The Death of Pushkin”, “Igor Savvovich”, for the play “Heart of a Dog”.

Tishchenko graduated from the Leningrad Conservatory (1962-63), his teachers in composition were V. Salmanov, V. Voloshin, O. Evlakhov, in graduate school – D. Shostakovich, in piano – A. Logovinsky. Now he himself is a professor at the Leningrad Conservatory.

Tishchenko developed as a composer very early – at the age of 18 he wrote the Violin Concerto, at 20 – the Second Quartet, which were among his best compositions. In his work, the folk-old line and the line of modern emotional expression stood out most prominently. In a new way, illuminating the images of ancient Russian history and Russian folklore, the composer admires the color of the archaic, seeks to convey the popular worldview that has developed over the centuries (ballet Yaroslavna – 1974, Third Symphony – 1966, parts of the Second (1959), Third Quartets (1970), Third Piano Sonata – 1965). The Russian lingering song for Tishchenko is both a spiritual and an aesthetic ideal. Comprehension of the deep layers of national culture allowed the composer in the Third Symphony to create a new type of musical composition – as it were, a “symphony of tunes”; where the orchestral fabric is woven from replicas of instruments. The soulful music of the finale of the symphony is associated with the image of N. Rubtsov’s poem – “my quiet homeland”. It is noteworthy that the ancient worldview attracted Tishchenko also in connection with the culture of the East, in particular due to the study of medieval Japanese music “gagaku”. Comprehending the specific features of the Russian folk and ancient Eastern worldview, the composer developed in his style a special type of musical development – meditative statics, in which changes in the character of music occur very slowly and gradually (long cello solo in the First Cello Concerto – 1963).

In the embodiment of typical for the XX century. images of struggle, overcoming, the tragic grotesque, the highest spiritual tension, Tishchenko acts as a successor to the symphonic dramas of his teacher Shostakovich. Particularly striking in this regard are the Fourth and Fifth Symphonies (1974 and 1976).

The Fourth Symphony is extremely ambitious – it was written for 145 musicians and a reader with a microphone and has a length of more than an hour and a half (that is, a whole symphony concerto). The Fifth Symphony is dedicated to Shostakovich and directly continues the imagery of his music – imperious oratorical proclamations, feverish pressures, tragic climaxes, and along with this – long monologues. It is permeated with the motif-monogram of Shostakovich (D-(e)S-С-Н), includes quotations from his works (from the Eighth and Tenth Symphonies, the Sonata for Viola, etc.), as well as from the works of Tishchenko (from the Third Symphony, the Fifth Piano Sonata, Piano Concerto). This is a kind of dialogue between a younger contemporary and an older one, a “relay race of generations”.

Impressions from Shostakovich’s music were also reflected in two sonatas for violin and piano (1957 and 1975). In the Second Sonata, the main image that begins and ends the work is a pathetic oratorical speech. This sonata is very unusual in composition – it consists of 7 parts, in which the odd ones make up the logical “framework” (Prelude, Sonata, Aria, Postlude), and the even ones are expressive “intervals” (Intermezzo I, II, III in presto tempo). The ballet “Yaroslavna” (“Eclipse”) was written based on the outstanding literary monument of Ancient Russia – “The Tale of Igor’s Campaign” (libre by O. Vinogradov).

The orchestra in the ballet is complemented by a choral part that enhances the Russian intonation flavor. In contrast to the interpretation of the plot in A. Borodin’s opera “Prince Igor”, the composer of the XNUMXth century. the tragedy of the defeat of Igor’s troops is emphasized. The original musical language of the ballet includes harsh chants that sound from the male choir, energetic offensive rhythms of a military campaign, mournful “howls” from the orchestra (“The Steppe of Death”), dreary wind tunes, reminiscent of the sound of pity.

The First Concerto for Cello and Orchestra has a special concept. “Something like a letter to a friend,” the author said of him. A new type of musical development is realized in the composition, similar to the organic growth of a plant from a grain. The concerto begins with a single cello sound, which further expands into “spurs, shoots.” As if by itself, a melody is born, becoming the author’s monologue, “confession of the soul.” And after the narrative beginning, the author sets out a stormy drama, with a sharp climax, followed by a departure into the sphere of enlightened reflection. “I know Tishchenko’s first cello concerto by heart,” said Shostakovich. Like all composing works of the last decades of the XNUMXth century, Tishchenko’s music evolves towards vocality, which goes back to the origins of musical art.

V. Kholopova