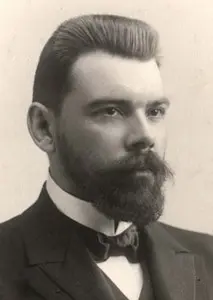

Alexey Fedorovich Lvov (Alexei Lvov) |

Alexei Lvov

Until the middle of the XNUMXth century, the so-called “enlightened amateurism” played an important role in Russian musical life. Home music-making was widely used in the nobility and aristocratic environment. Ever since the era of Peter I, music has become an integral part of noble education, which led to the emergence of a significant number of musically educated people who perfectly played one or another instrument. One of these “amateurs” was the violinist Alexei Fedorovich Lvov.

An extremely reactionary personality, a friend of Nicholas I and Count Benckendorff, the author of the official anthem of Tsarist Russia (“God Save the Tsar”), Lvov was a mediocre composer, but an outstanding violinist. When Schumann heard his play in Leipzig, he dedicated enthusiastic lines to him: “Lvov is such a wonderful and rare performer that he can be put on a par with first-class artists. If there are still such amateurs in the Russian capital, then another artist could rather learn there than teach himself.

Lvov’s playing made a deep impression on young Glinka: “On one of my father’s visits to St. Petersburg,” Glinka recalls, “he took me to the Lvovs, and the gentle sounds of Alexei Fedorovich’s sweet violin were deeply engraved in my memory.”

A. Serov gave a high assessment of Lvov’s playing: “The singing of the bow in Allegro,” he wrote, “the purity of intonation and the dapperness of the“ decoration ”in the passages, the expressiveness, reaching the fiery fascination – all this to the same extent as A.F. Few of the virtuosos in the world possessed lions.

Alexei Fedorovich Lvov was born on May 25 (June 5, according to the new style), 1798, into a wealthy family that belonged to the highest Russian aristocracy. His father, Fedor Petrovich Lvov, was a member of the State Council. A musically educated person, after the death of D.S. Bortnyansky, he took the post of director of the court Singing Chapel. From him this position passed to his son.

The father early recognized the musical talent of his son. He “saw in me a decisive talent for this art,” recalled A. Lvov. “I was constantly with him and from the age of seven, for better or worse, I played with him and my uncle Andrei Samsonovich Kozlyaninov, all the notes of ancient writers that the father wrote out from all European countries.”

On the violin, Lvov studied with the best teachers in St. Petersburg – Kaiser, Witt, Bo, Schmidecke, Lafon and Boehm. It is characteristic that only one of them, Lafont, often called the “French Paganini”, belonged to the virtuoso-romantic trend of violinists. The rest were followers of the classical school of Viotti, Bayo, Rode, Kreutzer. They instilled in their pet a love for Viotti and a dislike for Paganini, whom Lvov contemptuously called “the plasterer.” Of the Romantic violinists, he mostly recognized Spohr.

Violin lessons with teachers continued until the age of 19, and then Lvov improved his playing on his own. When the boy was 10 years old, his mother died. The father soon remarried, but his children established the best relationship with their stepmother. Lvov remembers her with great warmth.

Despite Lvov’s talent, his parents did not at all think about his career as a professional musician. Artistic, musical, literary activities were considered humiliating for the nobles, they were engaged in art only as amateurs. Therefore, in 1814, the young man was assigned to the Institute of Communications.

After 4 years, he brilliantly graduated from the institute with a gold medal and was sent to work in the military settlements of the Novgorod province, which were under the command of Count Arakcheev. Many years later, Lvov recalled this time and the cruelties that he witnessed with horror: “During the work, general silence, suffering, grief on the faces! Thus passed the days, months, without any rest, except for Sundays, on which the guilty were usually punished during the week. I remember that once on Sunday I rode about 15 versts, I did not pass a single village where I did not hear beatings and screams.

However, the camp situation did not prevent Lvov from getting close to Arakcheev: “After several years, I had more chances to see Count Arakcheev, who, despite his cruel temper, finally fell in love with me. None of my comrades was so distinguished by him, none of them received so many awards.

With all the difficulties of the service, the passion for music was so strong that Lvov even in the Arakcheev camps practiced the violin every day for 3 hours. Only 8 years later, in 1825, he returned to St. Petersburg.

During the Decembrist uprising, the “loyal” Lvov family, of course, remained aloof from the events, but they also had to endure the unrest. One of Alexei’s brothers, Ilya Fedorovich, the captain of the Izmailovsky regiment, was under arrest for several days, the husband of Darya Feodorovna’s sister, a close friend of Prince Obolensky and Pushkin, barely escaped hard labor.

When the events ended, Alexey Fedorovich met the chief of the gendarme corps, Benckendorff, who offered him the place of his adjutant. This happened on November 18, 1826.

In 1828, the war with Turkey began. It turned out to be favorable for Lvov’s promotion through the ranks. Adjutant Benkendorf arrived in the army and was soon enlisted in the personal retinue of Nicholas I.

Lvov scrupulously describes in his “Notes” his trips with the king and the events he witnessed. He attended the coronation of Nicholas I, traveled with him to Poland, Austria, Prussia, etc.; he became one of the close associates of the king, as well as his court composer. In 1833, at the request of Nicholas, Lvov composed a hymn that became the official anthem of Tsarist Russia. The words to the anthem were written by the poet Zhukovsky. For intimate royal holidays, Lvov composes musical pieces and they are played out by Nikolai (on the trumpet), the Empress (on the piano) and high-ranking amateurs – Vielgorsky, Volkonsky and others. He also composes other “official” music. The tsar generously showers him with orders and honors, makes him a cavalry guard, and on April 22, 1834, promotes him to the adjutant wing. The tsar becomes his “family” friend: at the wedding of his favorite (Lvov married Praskovya Ageevna Abaza on November 6, 1839), he, together with Countess his home musical evenings.

Lvov’s other friend is Count Benckendorff. Their relationship is not limited to service – they often visit each other.

While traveling around Europe, Lvov met many outstanding musicians: in 1838 he played quartets with Berio in Berlin, in 1840 he gave concerts with Liszt in Ems, performed at the Gewandhaus in Leipzig, in 1844 he played in Berlin with the cellist Kummer. Here Schumann heard him, who later responded with his commendable article.

In Lvov’s Notes, despite their boastful tone, there is much that is curious about these meetings. He describes playing music with Berio as follows: “I had some free time in the evenings and I decided to play quartets with him, and for this I asked him and the two Ganz brothers to play viola and cello; invited the famous Spontini and two or three other real hunters to his audience. Lvov played the second violin part, then asked Berio for permission to play the first violin part in both allegroes of Beethoven’s E-minor Quartet. When the performance ended, an excited Berio said: “I would never have believed that an amateur, busy with so many things like you, could raise his talent to such a degree. You are a real artist, you play the violin amazingly, and your instrument is magnificent.” Lvov played the Magini violin, bought by his father from the famous violinist Jarnovik.

In 1840, Lvov and his wife traveled around Germany. This was the first trip not related to court service. In Berlin, he took composition lessons from Spontini and met Meyerbeer. After Berlin, the Lvov couple went to Leipzig, where Alexei Fedorovich became close to Mendelssohn. The meeting with the outstanding German composer is one of the notable milestones in his life. After the performance of Mendelssohn’s quartets, the composer told Lvov: “I have never heard my music performed like this; it is impossible to convey my thoughts with greater accuracy; you guessed the slightest of my intentions.

From Leipzig, Lvov travels to Ems, then to Heidelberg (here he composes a violin concerto), and after traveling to Paris (where he met Baio and Cherubini), he returns to Leipzig. In Leipzig, Lvov’s public performance took place at the Gewandhaus.

Let’s talk about him in the words of Lvov himself: “On the very next day of our arrival in Leipzig, Mendelssohn came to me and asked me to go to the Gewandhaus with the violin, and he took my notes. Arriving in the hall, I found a whole orchestra that was waiting for us. Mendelssohn took the place of the conductor and asked me to play. There was no one in the hall, I played my concert, Mendelssohn led the orchestra with incredible skill. I thought that it was all over, put down the violin and was about to go, when Mendelssohn stopped me and said: “Dear friend, it was only a rehearsal for the orchestra; wait a little and be so kind as to replay the same pieces.” With this word, the doors opened, and a crowd of people poured into the hall; in a few minutes the hall, the entrance hall, everything was filled with people.

For a Russian aristocrat, public speaking was considered indecent; lovers of this circle were allowed to take part only in charity concerts. Therefore, Lvov’s embarrassment, which Mendelssohn hastened to dispel, is quite understandable: “Do not be afraid, this is a selected society that I myself invited, and after the music you will know the names of all the people in the hall.” And indeed, after the concert, the porter gave Lvov all the tickets with the names of the guests written by Mendelssohn’s hand.

Lvov played a prominent but highly controversial role in Russian musical life. His activity in the field of art is marked not only by positive, but also by negative aspects. By nature, he was a small, envious, selfish person. The conservatism of views was complemented by lust for power and hostility, which clearly affected, for example, relations with Glinka. It is characteristic that in his “Notes” Glinka is hardly mentioned.

In 1836, old Lvov died, and after a while, the young General Lvov was appointed director of the court Singing Chapel in his place. His clashes in this post with Glinka, who served under him, are well known. “The director of the Capella, A.F. Lvov, made Glinka feel in every possible way that “in the service of His Majesty” he is not a brilliant composer, the glory and pride of Russia, but a subordinate person, an official who is strictly obliged to strictly observe the “table of ranks” and obey any order the nearest authorities. The composer’s clashes with the director ended with the fact that Glinka could not stand it and filed a letter of resignation.

However, it would be unfair to cross out Lvov’s activities in the Chapel on this basis alone and recognize them as completely harmful. According to contemporaries, the Chapel under his direction sang with unheard-of perfection. The merit of Lvov was also the organization of instrumental classes at the Chapel, where young singers from the boys’ choir who had fallen asleep could study. Unfortunately, the classes lasted only 6 years and were closed due to lack of funds.

Lvov was the organizer of the Concert Society, founded by him in St. Petersburg in 1850. D. Stasov gives the highest rating to the concerts of the society, however, noting that they were not available to the general public, since Lvov distributed tickets “between his acquaintances – the courtiers and the aristocracy.”

One cannot pass over in silence the musical evenings at Lvov’s home. Salon Lvov was considered one of the most brilliant in St. Petersburg. Musical circles and salons were at that time widespread in Russian life. Their popularity was facilitated by the nature of Russian musical life. Until 1859, public concerts of vocal and instrumental music could only be given during Lent, when all theaters were closed. The concert season lasted only 6 weeks a year, the rest of the time public concerts were not allowed. This gap was filled by home forms of music making.

In the salons and circles, a high musical culture matured, which already in the first half of the XNUMXth century gave rise to a brilliant galaxy of music critics, composers, and performers. Most of the outdoor concerts were superficially entertaining. Among the public, fascination with virtuosity and instrumental effects dominated. True connoisseurs of music gathered in circles and salons, real values of art were performed.

Over time, some of the salons, in terms of organization, seriousness and purposefulness of musical activity, turned into concert institutions of the philharmonic type – a kind of academy of fine arts at home (Vsevolozhsky in Moscow, brothers Vielgorsky, V.F. Odoevsky, Lvov – in St. Petersburg).

The poet M. A. Venevitinov wrote about the salon of the Vielgorskys: “In the 1830s and 1840s, understanding music was still a luxury in St. the works of Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Schumann and other classics were available only to selected visitors of the once famous musical evenings in the Vielgorsky house.

A similar assessment is given by the critic V. Lenz to the salon of Lvov: “Each educated member of St. Petersburg society knew this temple of musical art, visited at one time by members of the imperial family and the St. Petersburg high society; a temple that united for many years (1835-1855) representatives of power, art, wealth, taste and beauty of the capital.

Although the salons were intended mainly for persons of the “high society”, their doors were also opened for those who belonged to the world of art. Lvov’s house was visited by music critics Y. Arnold, V. Lenz, Glinka visited. Famous artists, musicians, artists even sought to attract to the salon. “Lvov and I saw each other often,” recalls Glinka, “during the winter at the beginning of 1837, he sometimes invited Nestor Kukolnik and Bryullov to his place and treated us in a friendly way. I’m not talking about music (he then played excellently Mozart and Haydn; I also heard a trio for three Bach violins from him). But he, wanting to bind artists to himself, did not spare even the cherished bottle of some rare wine.

Concerts in aristocratic salons were distinguished by a high artistic level. “In our musical evenings,” recalls Lvov, “the best artists participated: Thalberg, Ms. Pleyel on the piano, Servais on the cello; but the adornment of these evenings was the incomparable Countess Rossi. With what care I prepared these evenings, how many rehearsals happened! .. “

Lvov’s house, located on Karavannaya Street (now Tolmacheva Street), has not been preserved. You can judge the atmosphere of musical evenings by the colorful description left by a frequent visitor to these evenings, music critic V. Lenz. Symphonic concerts were usually given in a hall intended also for balls, quartet meetings took place in Lvov’s office: “From the rather low entrance hall, an elegant light staircase of gray marble with dark red railings leads so gently and conveniently to the first floor that you yourself don’t notice how they found themselves in front of the door leading directly to the quartet room of the householder. How many elegant dresses, how many lovely women passed through this door or waited behind it when it happened to be late and the quartet had already begun! Aleksey Fyodorovich would not have forgiven even the most beautiful beauty if she had come in during a musical performance. In the middle of the room was a quartet table, this altar of a four-part musical sacrament; in the corner, a piano by Wirth; about a dozen chairs, upholstered in red leather, stood near the walls for the most intimate ones. The rest of the guests, together with the mistresses of the house, the wife of Alexei Fedorovich, his sister and stepmother, listened to music from the nearest living room.

Quartet evenings in Lvov enjoyed exceptional popularity. For 20 years, a quartet was assembled, which, in addition to Lvov, included Vsevolod Maurer (2nd violin), Senator Vilde (viola) and Count Matvei Yuryevich Vielgorsky; he was sometimes replaced by the professional cellist F. Knecht. “It happened to me a lot to hear good ensemble quartets,” writes J. Arnold, “for example, the older and younger Muller brothers, the Leipzig Gewandhaus quartet headed by Ferdinand David, Jean Becker and others, but in fairness and conviction I must admit that in I have never heard a quartet higher than Lvov’s in terms of sincere and refined artistic performance.

However, Lvov’s nature apparently also affected his quartet performance – the desire to rule was manifested here too. “Aleksey Fedorovich always chose quartets in which he could shine, or in which his playing could reach its full effect, unique in the passionate expression of particulars and in understanding the whole.” As a result, Lvov often “performed not the original creation, but a spectacular reworking of it by Lvov.” “Lvov conveyed Beethoven amazingly, fascinatingly, but with no less arbitrariness than Mozart.” However, subjectivism was a frequent phenomenon in the performing arts of the Romantic era, and Lvov was no exception.

Being a mediocre composer, Lvov sometimes achieved success in this field as well. Of course, his colossal connections and high position greatly contributed to the promotion of his work, but this is hardly the only reason for recognition in other countries.

In 1831, Lvov reworked Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater into a full orchestra and choir, for which the St. Petersburg Philharmonic Society presented him with an honorary member’s diploma. Subsequently, for the same work, he was awarded the honorary title of composer of the Bologna Academy of Music. For two psalms composed in 1840 in Berlin, he was awarded the title of honorary member of the Berlin Academy of Singing and the Academy of St. Cecilia in Rome.

Lvov is the author of several operas. He turned to this genre late – in the second half of his life. The first-born was “Bianca and Gualtiero” – a 2-act lyric opera, first successfully staged in Dresden in 1844, then in St. Petersburg with the participation of the famous Italian artists Viardo, Rubini and Tamberlic. Petersburg production did not bring laurels to the author. Arriving at the premiere, Lvov even wanted to leave the theater, fearing failure. However, the opera still had some success.

The next work, the comic opera The Russian Peasant and the French Marauders, on the theme of the Patriotic War of 1812, is a product of chauvinistic bad taste. The best of his operas is Ondine (based on a poem by Zhukovsky). It was performed in Vienna in 1846, where it was well received. Lvov also wrote the operetta “Barbara”.

In 1858 he published the theoretical work “On Free or Asymmetrical Rhythm”. From Lvov’s violin compositions are known: two fantasies (the second for violin with orchestra and choir, both composed in the mid-30s); the concerto “In the form of a dramatic scene” (1841), eclectic in style, clearly inspired by the Viotti and Spohr concertos; 24 caprices for solo violin, provided in the form of a preface with an article called “Advice to a Beginner to Play the Violin”. In “Advice” Lvov defends the “classical” school, the ideal of which he sees in the performance of the famous French violinist Pierre Baio, and attacks Paganini, whose “method”, in his opinion, “does not lead anywhere.”

In 1857 Lvov’s health deteriorated. From this year, he gradually begins to move away from public affairs, in 1861 he resigns as director of the Chapel, closes in at home, finishing composing caprices.

On December 16, 1870, Lvov died in his estate Roman near the city of Kovno (now Kaunas).

L. Raaben