Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky |

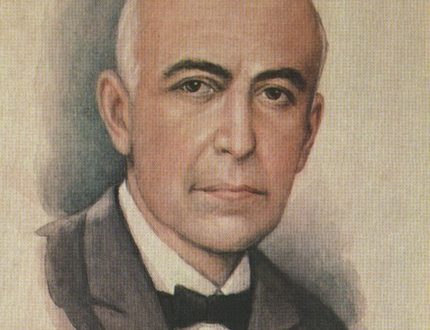

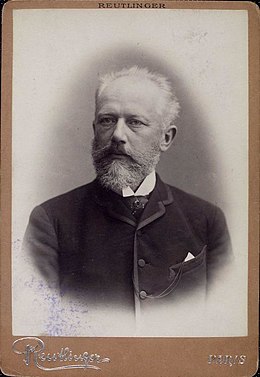

Pyotr Tchaikovsky

From century to century, from generation to generation, our love for Tchaikovsky, for his beautiful music, passes on, and this is its immortality. D. Shostakovich

“I would like with all the strength of my soul that my music spread, that the number of people who love it, find comfort and support in it, will increase.” In these words of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, the task of his art, which he saw in the service of music and people, in “truthfully, sincerely and simply” talking with them about the most important, serious and exciting things, is precisely defined. The solution of such a problem was possible with the development of the richest experience of Russian and world musical culture, with the mastery of the highest professional composing skills. The constant tension of creative forces, everyday and inspired work on the creation of numerous musical works made up the content and meaning of the whole life of the great artist.

Tchaikovsky was born into the family of a mining engineer. From early childhood, he showed an acute susceptibility to music, quite regularly studied the piano, which he was good at by the time he graduated from the School of Law in St. Petersburg (1859). Already serving in the Department of the Ministry of Justice (until 1863), in 1861 he entered the classes of the RMS, transformed into the St. Petersburg Conservatory (1862), where he studied composition with N. Zaremba and A. Rubinshtein. After graduating from the conservatory (1865), Tchaikovsky was invited by N. Rubinstein to teach at the Moscow Conservatory, which opened in 1866. The activity of Tchaikovsky (he taught classes of compulsory and special theoretical disciplines) laid the foundations of the pedagogical tradition of the Moscow Conservatory, this was facilitated by the creation of a textbook of harmony, translations of various teaching aids, etc. In 1868, Tchaikovsky first appeared in print with articles in support of N. Rimsky- Korsakov and M. Balakirev (friendly creative relations arose with him), and in 1871-76. was a musical chronicler for the newspapers Sovremennaya Letopis and Russkiye Vedomosti.

The articles, as well as extensive correspondence, reflected the aesthetic ideals of the composer, who had especially deep sympathy for the art of W. A. Mozart, M. Glinka, R. Schumann. Rapprochement with the Moscow Artistic Circle, which was headed by A. N. Ostrovsky (the first opera by Tchaikovsky “Voevoda” – 1868 was written based on his play; during the years of his studies – the overture “Thunderstorm”, in 1873 – music for the play “The Snow Maiden”), trips to Kamenka to see his sister A. Davydova contributed to the love that arose in childhood for folk tunes – Russian, and then Ukrainian, which Tchaikovsky often quotes in the works of the Moscow period of creativity.

In Moscow, the authority of Tchaikovsky as a composer is rapidly strengthening, his works are being published and performed. Tchaikovsky created the first classical examples of different genres in Russian music – symphonies (1866, 1872, 1875, 1877), string quartet (1871, 1874, 1876), piano concerto (1875, 1880, 1893), ballet (“Swan Lake”, 1875 -76), a concert instrumental piece (“Melancholic Serenade” for violin and orchestra – 1875; “Variations on a Rococo Theme” for cello and orchestra – 1876), writes romances, piano works (“The Seasons”, 1875-76, etc. ).

A significant place in the composer’s work was occupied by program symphonic works – the fantasy overture “Romeo and Juliet” (1869), the fantasy “The Tempest” (1873, both – after W. Shakespeare), the fantasy “Francesca da Rimini” (after Dante, 1876), in which the lyrical-psychological, dramatic orientation of Tchaikovsky’s work, manifested in other genres, is especially noticeable.

In the opera, searches following the same path lead him from everyday drama to a historical plot (“Oprichnik” based on the tragedy by I. Lazhechnikov, 1870-72) through an appeal to N. Gogol’s lyric-comedy and fantasy story (“Vakula the Blacksmith” – 1874, 2nd edition – “Cherevichki” – 1885) to Pushkin’s “Eugene Onegin” – lyrical scenes, as the composer (1877-78) called his opera.

“Eugene Onegin” and the Fourth Symphony, where the deep drama of human feelings is inseparable from the real signs of Russian life, became the result of the Moscow period of Tchaikovsky’s work. Their completion marked the exit from a severe crisis caused by an overstrain of creative forces, as well as an unsuccessful marriage. The financial support provided to Tchaikovsky by N. von Meck (correspondence with her, which lasted from 1876 to 1890, is invaluable material for studying the composer’s artistic views), gave him the opportunity to leave the work at the conservatory that weighed on him by that time and go abroad to improve health.

Works of the late 70’s – early 80’s. marked by greater objectivity of expression, the continuing expansion of the range of genres in instrumental music (Concerto for violin and orchestra – 1878; orchestral suites – 1879, 1883, 1884; Serenade for string orchestra – 1880; “Trio in Memory of the Great Artist” (N. Rubinstein) for piano , violins and cellos – 1882, etc.), the scale of opera ideas (“The Maid of Orleans” by F. Schiller, 1879; “Mazeppa” by A. Pushkin, 1881-83), further improvement in the field of orchestral writing (“Italian Capriccio” – 1880, suites), musical form, etc.

Since 1885, Tchaikovsky settled in the vicinity of Klin near Moscow (since 1891 – in Klin, where in 1895 the House-Museum of the composer was opened). The desire for solitude for creativity did not exclude deep and lasting contacts with Russian musical life, which developed intensively not only in Moscow and St. Petersburg, but also in Kyiv, Kharkov, Odessa, Tiflis, etc. Conducting performances that began in 1887 contributed to the widespread dissemination of music Tchaikovsky. Concert trips to Germany, the Czech Republic, France, England, America brought the composer worldwide fame; creative and friendly ties with European musicians are being strengthened (G. Bulow, A. Brodsky, A. Nikish, A. Dvorak, E. Grieg, C. Saint-Saens, G. Mahler, etc.). In 1893 Tchaikovsky was awarded the degree of Doctor of Music from the University of Cambridge in England.

In the works of the last period, which opens with the program symphony “Manfred” (according to J. Byron, 1885), the opera “The Enchantress” (according to I. Shpazhinsky, 1885-87), the Fifth Symphony (1888), there is a noticeable increase in the tragic beginning, culminating in absolute the peaks of the composer’s work – the opera The Queen of Spades (1890) and the Sixth Symphony (1893), where he rises to the highest philosophical generalization of the images of love, life and death. Next to these works, the ballets The Sleeping Beauty (1889) and The Nutcracker (1892), the opera Iolanthe (after G. Hertz, 1891) appear, culminating in the triumph of light and goodness. A few days after the premiere of the Sixth Symphony in St. Petersburg, Tchaikovsky died suddenly.

Tchaikovsky’s work embraced almost all musical genres, among which the most large-scale opera and symphony occupy the leading place. They reflect the composer’s artistic conception to the fullest extent, in the center of which are the deep processes of a person’s inner world, the complex movements of the soul, revealed in sharp and intense dramatic collisions. However, even in these genres, the main intonation of Tchaikovsky’s music is always heard – melodious, lyrical, born from a direct expression of human feeling and finding an equally direct response from the listener. On the other hand, other genres – from romance or piano miniature to ballet, instrumental concerto or chamber ensemble – can be endowed with the same qualities of symphonic scale, complex dramatic development and deep lyrical penetration.

Tchaikovsky also worked in the field of choral (including sacred) music, wrote vocal ensembles, music for dramatic performances. The traditions of Tchaikovsky in various genres have found their continuation in the work of S. Taneyev, A. Glazunov, S. Rachmaninov, A. Scriabin, and Soviet composers. The music of Tchaikovsky, which gained recognition even during his lifetime, which, according to B. Asafiev, became a “vital necessity” for people, captured a huge era of Russian life and culture of the XNUMXth century, went beyond them and became the property of all mankind. Its content is universal: it covers the images of life and death, love, nature, childhood, the surrounding life, it generalizes and reveals in a new way the images of Russian and world literature – Pushkin and Gogol, Shakespeare and Dante, Russian lyric poetry of the second half of the XNUMXth century.

The music of Tchaikovsky, embodying the precious qualities of Russian culture – love and compassion for man, extraordinary sensitivity to the restless searches of the human soul, intolerance to evil and a passionate thirst for goodness, beauty, moral perfection – reveals deep connections with the work of L. Tolstoy and F. Dostoevsky, I. Turgenev and A. Chekhov.

Today, Tchaikovsky’s dream of increasing the number of people who love his music is coming true. One of the testimonies of the world fame of the great Russian composer was the International Competition named after him, which attracts hundreds of musicians from different countries to Moscow.

E. Tsareva

musical position. Worldview. Milestones of the creative path

1

Unlike the composers of the “new Russian musical school” – Balakirev, Mussorgsky, Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov, who, for all the dissimilarity of their individual creative paths, acted as representatives of a certain direction, united by a commonality of main goals, objectives and aesthetic principles, Tchaikovsky did not belong to any what groups and circles. In the complex interweaving and struggle of various trends that characterized Russian musical life in the second half of the XNUMXth century, he maintained an independent position. Much brought him closer to the “Kuchkists” and caused mutual attraction, but there were disagreements between them, as a result of which a certain distance always remained in their relations.

One of the constant reproaches to Tchaikovsky, heard from the camp of the “Mighty Handful”, was the lack of a clearly expressed national character of his music. “The national element is not always successful for Tchaikovsky,” Stasov cautiously remarks in his long review article “Our Music of the Last 25 Years.” On another occasion, uniting Tchaikovsky with A. Rubinstein, he directly states that both composers “are far from being full representatives of the new Russian musicians and their aspirations: both of them are not independent enough, and they are not strong enough and national enough.”

The opinion that national Russian elements were alien to Tchaikovsky, about the excessively “Europeanized” and even “cosmopolitan” nature of his work was widely spread in his time and was expressed not only by critics who spoke on behalf of the “new Russian school”. In a particularly sharp and straightforward form, it is expressed by M. M. Ivanov. “Of all Russian authors,” the critic wrote almost twenty years after the composer’s death, “he [Tchaikovsky] remained forever the most cosmopolitan, even when he tried to think in Russian, to approach the well-known features of the emerging Russian musical warehouse.” “The Russian way of expressing himself, the Russian style, which we see, for example, in Rimsky-Korsakov, he does not have in sight …”.

For us, who perceive Tchaikovsky’s music as an integral part of Russian culture, of the entire Russian spiritual heritage, such judgments sound wild and absurd. The author of Eugene Onegin himself, constantly emphasizing his inextricable connection with the roots of Russian life and his passionate love for everything Russian, never ceased to consider himself a representative of native and closely related domestic art, whose fate deeply affected and worried him.

Like the “Kuchkists”, Tchaikovsky was a convinced Glinkian and bowed before the greatness of the feat accomplished by the creator of “Life for the Tsar” and “Ruslan and Lyudmila”. “An unprecedented phenomenon in the field of art”, “a real creative genius” – in such terms he spoke of Glinka. “Something overwhelming, gigantic”, similar to which “neither Mozart, nor Gluck, nor any of the masters” had, Tchaikovsky heard in the final chorus of “A Life for the Tsar”, which put its author “alongside (Yes! Alongside!) Mozart , with Beethoven and with anyone.” “No less manifestation of extraordinary genius” found Tchaikovsky in “Kamarinskaya”. His words that the entire Russian symphony school “is in Kamarinskaya, just like the whole oak tree is in the acorn,” became winged. “And for a long time,” he argued, “Russian authors will draw from this rich source, because it takes a lot of time and a lot of effort to exhaust all its wealth.”

But being as much a national artist as any of the “Kuchkists”, Tchaikovsky solved the problem of the folk and the national in his work in a different way and reflected other aspects of national reality. Most of the composers of The Mighty Handful, in search of an answer to the questions put forward by modernity, turned to the origins of Russian life, be it significant events of the historical past, epic, legend or ancient folk customs and ideas about the world. It cannot be said that Tchaikovsky was completely uninterested in all this. “… I have not yet met a person who is more in love with Mother Russia in general than I am,” he once wrote, “and in her Great Russian parts in particular <...> I passionately love a Russian person, Russian speech, a Russian mindset, Russian beauty persons, Russian customs. Lermontov directly says that dark antiquity cherished legends his souls do not move. And I even love it.”

But the main subject of Tchaikovsky’s creative interest was not the broad historical movements or the collective foundations of folk life, but the internal psychological collisions of the spiritual world of the human person. Therefore, the individual prevails in him over the universal, the lyric over the epic. With great power, depth and sincerity, he reflected in his music that rise in personal self-consciousness, that thirst for the liberation of the individual from everything that fetters the possibility of its full, unhindered disclosure and self-affirmation, which were characteristic of Russian society in the post-reform period. The element of the personal, the subjective, is always present in Tchaikovsky, no matter what topics he addresses. Hence the special lyrical warmth and penetration that fanned in his works pictures of folk life or the Russian nature he loves, and, on the other hand, the sharpness and tension of dramatic conflicts that arose from the contradiction between a person’s natural desire for the fullness of enjoying life and the harsh ruthless reality, on which it breaks.

Differences in the general direction of the work of Tchaikovsky and the composers of the “new Russian musical school” also determined some features of their musical language and style, in particular, their approach to the implementation of folk song thematics. For all of them, the folk song served as a rich source of new, nationally unique means of musical expression. But if the “Kuchkists” sought to discover in folk melodies the ancient features inherent in it and to find the methods of harmonic processing corresponding to them, then Tchaikovsky perceived the folk song as a direct element of the living surrounding reality. Therefore, he did not try to separate the true basis in it from the one introduced later, in the process of migration and transition to a different social environment, he did not separate the traditional peasant song from the urban one, which underwent transformation under the influence of romance intonations, dance rhythms, etc. melody, he processed it freely, subordinated it to his personal individual perception.

A certain prejudice on the part of the “Mighty Handful” manifested itself towards Tchaikovsky and as a pupil of the St. Petersburg Conservatory, which they considered a stronghold of conservatism and academic routine in music. Tchaikovsky is the only one of the Russian composers of the “sixties” generation who received a systematic professional education within the walls of a special musical educational institution. Rimsky-Korsakov later had to fill in the gaps in his professional training, when, having started teaching musical and theoretical disciplines at the conservatory, in his own words, “became one of its best students.” And it is quite natural that it was Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov who were the founders of the two largest composer schools in Russia in the second half of the XNUMXth century, conventionally called “Moscow” and “Petersburg”.

The conservatory not only armed Tchaikovsky with the necessary knowledge, but also instilled in him that strict discipline of labor, thanks to which he could create, in a short period of active creative activity, many works of the most diverse genre and character, enriching various areas of Russian musical art. Constant, systematic compositional work Tchaikovsky considered the obligatory duty of every true artist who takes his vocation seriously and responsibly. Only that music, he notes, can touch, shock and hurt, which has poured out from the depths of an artistic soul excited by inspiration <...> Meanwhile, you always need to work, and a real honest artist cannot sit idly by located”.

Conservative upbringing also contributed to the development in Tchaikovsky of a respectful attitude to tradition, to the heritage of the great classical masters, which, however, was in no way associated with a prejudice against the new. Laroche recalled the “silent protest” with which the young Tchaikovsky treated the desire of some teachers to “protect” their pupils from the “dangerous” influences of Berlioz, Liszt, Wagner, keeping them within the framework of classical norms. Later, the same Laroche wrote as about a strange misunderstanding about the attempts of some critics to classify Tchaikovsky as a composer of a conservative traditionalist direction and argued that “Mr. Tchaikovsky is incomparably closer to the extreme left of the musical parliament than to the moderate right.” The difference between him and the “Kuchkists”, in his opinion, is more “quantitative” than “qualitative”.

Laroche’s judgments, despite their polemical sharpness, are largely fair. No matter how sharp the disagreements and disputes between Tchaikovsky and the Mighty Handful sometimes took, they reflected the complexity and diversity of paths within the fundamentally united progressive democratic camp of Russian musicians of the second half of the XNUMXth century.

Close ties connected Tchaikovsky with the entire Russian artistic culture during its high classical heyday. A passionate lover of reading, he knew Russian literature very well and closely followed everything new that appeared in it, often expressing very interesting and thoughtful judgments about individual works. Bowing to the genius of Pushkin, whose poetry played a huge role in his own work, Tchaikovsky loved a lot from Turgenev, subtly felt and understood Fet’s lyrics, which did not prevent him from admiring the richness of descriptions of life and nature from such an objective writer as Aksakov.

But he assigned a very special place to L. N. Tolstoy, whom he called “the greatest of all artistic geniuses” that mankind has ever known. In the works of the great novelist Tchaikovsky was especially attracted by “some the highest love for man, supreme a pity to his helplessness, finiteness and insignificance. “The writer, who for nothing got to anyone before him the power not bestowed from above to compel us, poor in mind, to comprehend the most impenetrable nooks and crannies of the recesses of our moral life,” “the deepest heart-seller,” in such expressions he wrote about what, in his opinion, amounted to , strength and greatness of Tolstoy as an artist. “He alone is enough,” according to Tchaikovsky, “so that the Russian person does not bashfully bow his head when all the great things that Europe has created are calculated before him.”

More complex was his attitude towards Dostoevsky. Recognizing his genius, the composer did not feel such inner closeness to him as to Tolstoy. If, reading Tolstoy, he could shed tears of blessed admiration because “through his mediation touched with the world of the ideal, absolute goodness and humanity”, then the “cruel talent” of the author of “The Brothers Karamazov” suppressed him and even frightened him away.

Of the writers of the younger generation, Tchaikovsky had a special sympathy for Chekhov, in whose stories and novels he was attracted by a combination of merciless realism with lyrical warmth and poetry. This sympathy was, as you know, mutual. Chekhov’s attitude to Tchaikovsky is eloquently evidenced by his letter to the composer’s brother, where he admitted that “he is ready day and night to stand guard of honor at the porch of the house where Pyotr Ilyich lives” – so great was his admiration for the musician, to whom he assigned second place in Russian art, immediately after Leo Tolstoy. This assessment of Tchaikovsky by one of the greatest domestic masters of the word testifies to what the composer’s music was for the best progressive Russian people of his time.

2

Tchaikovsky belonged to the type of artists in whom the personal and the creative, the human and the artistic are so closely linked and intertwined that it is almost impossible to separate one from the other. Everything that worried him in life, caused pain or joy, indignation or sympathy, he sought to express in his compositions in the language of musical sounds close to him. The subjective and the objective, the personal and the impersonal are inseparable in Tchaikovsky’s work. This allows us to speak of lyricism as the main form of his artistic thinking, but in the broad meaning that Belinsky attached to this concept. “All common, everything substantial, every idea, every thought – the main engines of the world and life, – he wrote, – can make up the content of a lyrical work, but on the condition, however, that the general be translated into the subject’s blood property, enter into his sensation, be connected not with any one side of him, but with the whole integrity of his being. Everything that occupies, excites, pleases, saddens, delights, calms, disturbs, in a word, everything that makes up the content of the spiritual life of the subject, everything that enters into it, arises in it – all this is accepted by the lyric as its legitimate property. .

Lyricism as a form of artistic comprehension of the world, Belinsky further explains, is not only a special, independent kind of art, the scope of its manifestation is wider: “lyricism, existing in itself, as a separate kind of poetry, enters into all others, like an element, lives them , as the fire of Prometheans lives all the creations of Zeus … The preponderance of the lyrical element also happens in the epic and in the drama.

A breath of sincere and direct lyrical feeling fanned all of Tchaikovsky’s works, from intimate vocal or piano miniatures to symphonies and operas, which by no means excludes neither depth of thought nor strong and vivid drama. The work of a lyric artist is the broader in content, the richer his personality and the more diverse the range of her interests, the more responsive his nature is to the impressions of the surrounding reality. Tchaikovsky was interested in many things and reacted sharply to everything that happened around him. It can be argued that there was not a single major and significant event in his contemporary life that would leave him indifferent and did not cause one or another response from him.

By nature and way of thinking, he was a typical Russian intellectual of his time – a time of deep transformative processes, great hopes and expectations, and equally bitter disappointments and losses. One of the main features of Tchaikovsky as a person is the insatiable restlessness of the spirit, characteristic of many leading figures of Russian culture in that era. The composer himself defined this feature as “longing for the ideal.” Throughout his life, he intensely, sometimes painfully, sought a solid spiritual support, turning either to philosophy or to religion, but he could not bring his views on the world, on the place and purpose of a person in it into a single integral system. “… I do not find in my soul the strength to develop any strong convictions, because I, like a weather vane, turn between traditional religion and the arguments of a critical mind,” admitted the thirty-seven-year-old Tchaikovsky. The same motive sounds in a diary entry made ten years later: “Life passes, comes to an end, but I haven’t thought of anything, I even disperse it, if fatal questions come up, I leave them.”

Feeding an irresistible antipathy to all kinds of doctrinairism and dry rationalistic abstractions, Tchaikovsky was relatively little interested in various philosophical systems, but he knew the works of some philosophers and expressed his attitude towards them. He categorically condemned the philosophy of Schopenhauer, then fashionable in Russia. “In the final conclusions of Schopenhauer,” he finds, “there is something offensive to human dignity, something dry and selfish, not warmed by love for humanity.” The harshness of this review is understandable. The artist, who described himself as “a person passionately loving life (despite all its hardships) and equally passionately hating death,” could not accept and share the philosophical teaching that asserted that only the transition to non-existence, self-destruction serves as a deliverance from world evil.

On the contrary, Spinoza’s philosophy evoked sympathy from Tchaikovsky and attracted him with its humanity, attention and love for man, which allowed the composer to compare the Dutch thinker with Leo Tolstoy. The atheistic essence of Spinoza’s views did not go unnoticed by him either. “I forgot then,” notes Tchaikovsky, recalling his recent dispute with von Meck, “that there could be people like Spinoza, Goethe, Kant, who managed to do without religion? I forgot then that, not to mention these colossi, there is an abyss of people who have managed to create for themselves a harmonious system of ideas that have replaced religion for them.

These lines were written in 1877, when Tchaikovsky considered himself an atheist. A year later, he declared even more emphatically that the dogmatic side of Orthodoxy “had long been subjected in me to criticism that would kill him.” But in the early 80s, a turning point took place in his attitude to religion. “… The light of faith penetrates into my soul more and more,” he admitted in a letter to von Meck from Paris dated March 16/28, 1881, “… I feel that I am more and more inclined towards this only stronghold of ours against all kinds of disasters . I feel that I am beginning to know how to love God, which I did not know before. True, the remark immediately slips through: “doubts still visit me.” But the composer tries with all the strength of his soul to drown out these doubts and drives them away from himself.

Tchaikovsky’s religious views remained complex and ambiguous, based more on emotional stimuli than on deep and firm conviction. Some of the tenets of the Christian faith were still unacceptable to him. “I am not so imbued with religion,” he notes in one of the letters, “to see with confidence the beginning of a new life in death.” The idea of eternal heavenly bliss seemed to Tchaikovsky something extremely dull, empty and joyless: “Life is then charming when it consists of alternating joys and sorrows, of the struggle between good and evil, of light and shadow, in a word, of diversity in unity. How can we imagine eternal life in the form of endless bliss?

In 1887, Tchaikovsky wrote in his diary:religion I would like to expound mine sometime in detail, if only in order to myself once and for all understand my beliefs and the boundary where they begin after speculation. However, Tchaikovsky apparently failed to bring his religious views into a single system and resolve all their contradictions.

He was attracted to Christianity mainly by the moral humanistic side, the gospel image of Christ was perceived by Tchaikovsky as living and real, endowed with ordinary human qualities. “Although He was God,” we read in one of the diary entries, “but at the same time He was also a man. He suffered, as did we. We regret him, we love in him his ideal human sides.” The idea of the almighty and formidable God of hosts was for Tchaikovsky something distant, difficult to understand and inspires fear rather than trust and hope.

The great humanist Tchaikovsky, for whom the highest value was the human person conscious of his dignity and his duty to others, thought little about the issues of the social structure of life. His political views were quite moderate and did not go beyond thoughts of a constitutional monarchy. “How bright Russia would be,” he remarks one day, “if the sovereign (meaning Alexander II) ended his amazing reign by granting us political rights! Let them not say that we have not matured to constitutional forms.” Sometimes this idea of a constitution and popular representation in Tchaikovsky took the form of the idea of a Zemstvo sobor, widespread in the 70s and 80s, shared by various circles of society from the liberal intelligentsia to the revolutionaries of the People’s Volunteers.

Far from sympathizing with any revolutionary ideals, at the same time, Tchaikovsky was hard pressed by the ever-increasing rampant reaction in Russia and condemned the cruel government terror aimed at suppressing the slightest glimpse of discontent and free thought. In 1878, at the time of the highest rise and growth of the Narodnaya Volya movement, he wrote: “We are going through a terrible time, and when you start to think about what is happening, it becomes terrible. On the one hand, the completely dumbfounded government, so lost that Aksakov is cited for a bold, truthful word; on the other hand, unfortunate crazy youth, exiled by the thousands without trial or investigation to where the raven has not brought bones – and among these two extremes of indifference to everything, the mass, mired in selfish interests, without any protest looking at one or the other.

This kind of critical statements are repeatedly found in Tchaikovsky’s letters and later. In 1882, shortly after the accession of Alexander III, accompanied by a new intensification of reaction, the same motive sounds in them: “For our dear heart, although a sad fatherland, a very gloomy time has come. Everyone feels a vague unease and discontent; everyone feels that the state of affairs is unstable and that changes must take place – but nothing can be foreseen. In 1890, the same motive sounds again in his correspondence: “… something is wrong in Russia now … The spirit of reaction reaches the point that the writings of Count. L. Tolstoy are persecuted as some kind of revolutionary proclamations. The youth is revolting, and the Russian atmosphere is, in fact, very gloomy.” All this, of course, influenced the general state of mind of Tchaikovsky, exacerbated the feeling of discord with reality and gave rise to an internal protest, which was also reflected in his work.

A man of broad versatile intellectual interests, an artist-thinker, Tchaikovsky was constantly weighed down by a deep, intense thought about the meaning of life, his place and purpose in it, about the imperfection of human relations, and about many other things that contemporary reality made him think about. The composer could not but worry about the general fundamental questions concerning the foundations of artistic creativity, the role of art in people’s lives and the ways of its development, on which such sharp and heated disputes were conducted in his time. When Tchaikovsky answered the questions addressed to him that music should be written “as God puts on the soul,” this manifested his irresistible antipathy to any kind of abstract theorizing, and even more so to the approval of any obligatory dogmatic rules and norms in art. . So, reproaching Wagner for forcibly subordinating his work to an artificial and far-fetched theoretical concept, he remarks: “Wagner, in my opinion, killed the enormous creative power in himself with theory. Any preconceived theory cools the immediate creative feeling.

Appreciating in music, first of all, sincerity, truthfulness and immediacy of expression, Tchaikovsky avoided loud declarative statements and proclaiming his tasks and principles for their implementation. But this does not mean that he did not think about them at all: his aesthetic convictions were quite firm and consistent. In the most general form, they can be reduced to two main provisions: 1) democracy, the belief that art should be addressed to a wide range of people, serve as a means of their spiritual development and enrichment, 2) the unconditional truth of life. The well-known and often quoted words of Tchaikovsky: “I would wish with all the strength of my soul that my music spread, that the number of people who love it, find comfort and support in it” would increase, were a manifestation of a non-vain pursuit of popularity at all costs, but the composer’s inherent need to communicate with people through his art, the desire to bring them joy, to strengthen the strength and good spirits.

Tchaikovsky constantly talks about the truth of the expression. At the same time, he sometimes showed a negative attitude towards the word “realism”. This is explained by the fact that he perceived it in a superficial, vulgar Pisarev interpretation, as excluding sublime beauty and poetry. He considered the main thing in art not external naturalistic plausibility, but the depth of comprehension of the inner meaning of things and, above all, those subtle and complex psychological processes hidden from a superficial glance that occur in the human soul. It is music, in his opinion, more than any other of the arts, that has this ability. “In an artist,” Tchaikovsky wrote, “there is absolute truth, not in a banal protocol sense, but in a higher one, opening up some unknown horizons to us, some inaccessible spheres where only music can penetrate, and no one has gone so far between writers. like Tolstoy.”

Tchaikovsky was not alien to the tendency to romantic idealization, to the free play of fantasy and fabulous fiction, to the world of the wonderful, magical and unprecedented. But the focus of the composer’s creative attention has always been a living real person with his simple but strong feelings, joys, sorrows and hardships. That sharp psychological vigilance, spiritual sensitivity and responsiveness with which Tchaikovsky was endowed allowed him to create unusually vivid, vitally truthful and convincing images that we perceive as close, understandable and similar to us. This puts him on a par with such great representatives of Russian classical realism as Pushkin, Turgenev, Tolstoy or Chekhov.

3

It can be rightly said about Tchaikovsky that the era in which he lived, a time of high social upsurge and great fruitful changes in all areas of Russian life, made him a composer. When a young official of the Ministry of Justice and an amateur musician, having entered the St. Petersburg Conservatory, which had just opened in 1862, soon decided to devote himself to music, this caused not only surprise, but also disapproval among many people close to him. Not devoid of a certain risk, Tchaikovsky’s act was not, however, accidental and thoughtless. A few years earlier, Mussorgsky had retired from military service for the same purpose, against the advice and persuasion of his older friends. Both brilliant young people were prompted to take this step by the attitude towards art, which is affirming in society, as a serious and important matter that contributes to the spiritual enrichment of people and the multiplication of national cultural heritage.

Tchaikovsky’s entry into the path of professional music was associated with a profound change in his views and habits, attitude to life and work. The composer’s younger brother and first biographer M. I. Tchaikovsky recalled how even his appearance had changed after entering the conservatory: in other respects.” With the demonstrative carelessness of the toilet, Tchaikovsky wanted to emphasize his decisive break with the former nobility and bureaucratic environment and the transformation from a polished secular man into a worker-raznochintsy.

In a little over three years of study at the conservatory, where A. G. Rubinshtein was one of his main mentors and leaders, Tchaikovsky mastered all the necessary theoretical disciplines and wrote a number of symphonic and chamber works, although not yet completely independent and uneven, but marked by extraordinary talent. The largest of these was the cantata “To Joy” on the words of Schiller’s ode, performed at the solemn graduation act on December 31, 1865. Shortly after that, Tchaikovsky’s friend and classmate Laroche wrote to him: “You are the greatest musical talent of modern Russia… I see in you the greatest, or rather, the only hope of our musical future… However, everything you have done… I consider only the work of a schoolboy.” , preparatory and experimental, so to speak. Your creations will begin, perhaps, only in five years, but they, mature, classical, will surpass everything that we had after Glinka.

Tchaikovsky’s independent creative activity unfolded in the second half of the 60s in Moscow, where he moved in early 1866 at the invitation of N. G. Rubinshtein to teach in the music classes of the RMS, and then at the Moscow Conservatory, which opened in the autumn of the same year. “… For P. I. Tchaikovsky,” as one of his new Moscow friends N. D. Kashkin testifies, “for many years she became that artistic family in whose environment his talent grew and developed.” The young composer met with sympathy and support not only in the musical, but also in the literary and theatrical circles of the then Moscow. Acquaintance with A. N. Ostrovsky and some of the leading actors of the Maly Theater contributed to Tchaikovsky’s growing interest in folk songs and ancient Russian life, which was reflected in his works of these years (the opera The Voyevoda based on Ostrovsky’s play, the First Symphony “Winter Dreams”) .

The period of unusually rapid and intensive growth of his creative talent was the 70s. “There is such a heap of preoccupation,” he wrote, “which embraces you so much during the height of work that you do not have time to take care of yourself and forget everything except what is directly related to work.” In this state of genuine obsession with Tchaikovsky, three symphonies, two piano and violin concertos, three operas, the Swan Lake ballet, three quartets and a number of others, including quite large and significant works, were created before 1878. If we add to this a large, time-consuming pedagogical work at the conservatory and continued cooperation in Moscow newspapers as a music columnist until the mid-70s, then one is involuntarily struck by the enormous energy and inexhaustible flow of his inspiration.

The creative pinnacle of this period were two masterpieces – “Eugene Onegin” and the Fourth Symphony. Their creation coincided with an acute mental crisis that brought Tchaikovsky to the brink of suicide. The immediate impetus for this shock was the marriage to a woman, the impossibility of living together with whom was realized from the very first days by the composer. However, the crisis was prepared by the totality of the conditions of his life and the heap over a number of years. “An unsuccessful marriage accelerated the crisis,” B.V. Asafiev rightly notes, “because Tchaikovsky, having made a mistake in counting on the creation of a new, more creatively more favorable – family – environment in the given living conditions, quickly broke free – to complete creative freedom. That this crisis was not of a morbid nature, but was prepared by the entire impetuous development of the composer’s work and the feeling of the greatest creative upsurge, is shown by the result of this nervous outburst: the opera Eugene Onegin and the famous Fourth Symphony.

When the severity of the crisis abated somewhat, the time came for a critical analysis and revision of the entire path traveled, which dragged on for years. This process was accompanied by bouts of sharp dissatisfaction with himself: more and more often complaints are heard in Tchaikovsky’s letters about the lack of skill, immaturity and imperfection of everything he has written so far; sometimes it seems to him that he is exhausted, exhausted and will no longer be able to create anything of any significance. A more sober and calm self-assessment is contained in a letter to von Meck dated May 25-27, 1882: “… An undoubted change has occurred in me. There is no longer that lightness, that pleasure in work, thanks to which days and hours flew by unnoticed for me. I console myself with the fact that if my subsequent writings are less warmed by true feeling than the previous ones, then they will win in texture, will be more deliberate, more mature.

The period from the end of the 70s to the middle of the 80s in Tchaikovsky’s development can be defined as a period of searching and accumulation of strength to master new great artistic tasks. His creative activity did not decrease during these years. Thanks to the financial support of von Meck, Tchaikovsky was able to free himself from his burdensome work in the theoretical classes of the Moscow Conservatory and devote himself entirely to composing music. A number of works come out from under his pen, perhaps not possessing such a captivating dramatic power and intensity of expression as Romeo and Juliet, Francesca or the Fourth Symphony, such a charm of warm soulful lyricism and poetry as Eugene Onegin, but masterful, impeccable in form and texture, written with great imagination, witty and inventive, and often with genuine brilliance. These are the three magnificent orchestral suites and some other symphonic works of these years. The operas The Maid of Orleans and Mazeppa, created at the same time, are distinguished by their breadth of forms, their desire for sharp, tense dramatic situations, although they suffer from some internal contradictions and a lack of artistic integrity.

These searches and experiences prepared the composer for the transition to a new stage of his work, marked by the highest artistic maturity, a combination of depth and significance of ideas with the perfection of their implementation, richness and variety of forms, genres and means of musical expression. In such works of the middle and second half of the 80s as “Manfred”, “Hamlet”, the Fifth Symphony, in comparison with the earlier works of Tchaikovsky, features of greater psychological depth, concentration of thought appear, tragic motives are intensified. In the same years, his work achieves wide public recognition both at home and in a number of foreign countries. As Laroche once remarked, for Russia in the 80s he becomes the same as Verdi was for Italy in the 50s. The composer, who sought solitude, now willingly appears before the public and performs on the concert stage himself, conducting his works. In 1885, he was elected chairman of the Moscow branch of the RMS and took an active part in organizing the concert life of Moscow, attending exams at the conservatory. Since 1888, his triumphal concert tours began in Western Europe and the United States of America.

Intense musical, public and concert activity does not weaken Tchaikovsky’s creative energy. In order to concentrate on composing music in his spare time, he settled in the vicinity of Klin in 1885, and in the spring of 1892 he rented a house on the outskirts of the city of Klin itself, which remains to this day the place of memory of the great composer and the main repository of his richest manuscript heritage.

The last five years of the composer’s life were marked by a particularly high and bright flowering of his creative activity. In the period 1889 – 1893 he created such wonderful works as the operas “The Queen of Spades” and “Iolanthe”, the ballets “Sleeping Beauty” and “The Nutcracker” and, finally, unparalleled in the power of tragedy, the depth of the formulation of questions of human life and death, courage and at the same time clarity, completeness of the artistic concept of the Sixth (“Pathetic”) Symphony. Having become the result of the entire life and creative path of the composer, these works were at the same time a bold breakthrough into the future and opened up new horizons for the domestic musical art. Much in them is now perceived as an anticipation of what was later achieved by the great Russian musicians of the XNUMXth century – Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Shostakovich.

Tchaikovsky did not have to go through the pores of creative decline and withering – an unexpected catastrophic death overtook him at a moment when he was still full of strength and was at the top of his mighty genius talent.

* * *

The music of Tchaikovsky, already during his lifetime, entered the consciousness of broad sections of Russian society and became an integral part of the national spiritual heritage. His name is on a par with the names of Pushkin, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and other greatest representatives of Russian classical literature and artistic culture in general. The unexpected death of the composer in 1893 was perceived by the entire enlightened Russia as an irreparable national loss. What he was for many thinking educated people is eloquently evidenced by the confession of V. G. Karatygin, all the more valuable because it belongs to a person who subsequently accepted Tchaikovsky’s work far from unconditionally and with a significant degree of criticism. In an article dedicated to the twentieth anniversary of his death, Karatygin wrote: “… When Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky died in St. Petersburg from cholera, when the author of Onegin and The Queen of Spades was no more in the world, for the first time I was able not only to understand the size of the loss , incurred by the Russian societybut also painful to feel heart of all-Russian grief. For the first time, on this basis, I felt my connection with society in general. And because then it happened for the first time, that I owe Tchaikovsky the first awakening in myself of the feeling of a citizen, a member of Russian society, the date of his death still has some special meaning for me.

The power of suggestion that emanated from Tchaikovsky as an artist and a person was enormous: not a single Russian composer who began his creative activity in the last decades of the 900th century escaped his influence to one degree or another. At the same time, in the 910s and early XNUMXs, in connection with the spread of symbolism and other new artistic movements, strong “anti-Chaikovist” tendencies emerged in some musical circles. His music begins to seem too simple and mundane, devoid of impulse to “other worlds”, to the mysterious and unknowable.

In 1912, N. Ya. Myaskovsky resolutely spoke out against the tendentious disdain for Tchaikovsky’s legacy in the well-known article “Tchaikovsky and Beethoven.” He indignantly rejected the attempts of some critics to belittle the importance of the great Russian composer, “whose work not only gave mothers the opportunity to become on a level with all other cultural nations in their own recognition, but thereby prepared free paths for the coming superiority …”. The parallel that has now become familiar to us between the two composers whose names are compared in the title of the article could then seem to many bold and paradoxical. Myaskovsky’s article evoked conflicting responses, including sharply polemical ones. But there were speeches in the press that supported and developed the thoughts expressed in it.

Echoes of that negative attitude towards Tchaikovsky’s work, which stemmed from the aesthetic hobbies of the beginning of the century, were also felt in the 20s, bizarrely intertwining with the vulgar sociological trends of those years. At the same time, it was this decade that was marked by a new rise in interest in the legacy of the great Russian genius and a deeper understanding of its significance and meaning, in which great merit belongs to B. V. Asafiev as a researcher and propagandist. Numerous and varied publications in the following decades revealed the richness and versatility of Tchaikovsky’s creative image as one of the greatest humanist artists and thinkers of the past.

Disputes about the value of Tchaikovsky’s music have long ceased to be relevant for us, its high artistic value not only does not decrease in the light of the latest achievements of Russian and world musical art of our time, but is constantly growing and revealing itself deeper and wider, from new sides, unnoticed or underestimated by contemporaries and representatives of the next generation that followed him.

Yu. Come on

- Opera works by Tchaikovsky →

- Ballet creativity of Tchaikovsky →

- Symphonic works of Tchaikovsky →

- Piano works by Tchaikovsky →

- Romances by Tchaikovsky →

- Choral works by Tchaikovsky →