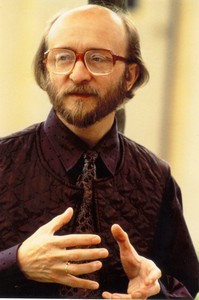

Alexander Alexandrovich Slobodyanik |

Alexander Slobodyanik

Alexander Alexandrovich Slobodyanik from a young age was in the center of attention of specialists and the general public. Today, when he has many years of concert performance under his belt, one can say without fear of making a mistake that he was and remains one of the most popular pianists of his generation. He is spectacular on the stage, he has an imposing appearance, in the game one can feel a large, peculiar talent – one can feel it right away, from the very first notes he takes. And yet, the public’s sympathy for him is due, perhaps, to reasons of a special nature. Talented and, moreover, outwardly spectacular on the concert stage is more than enough; Slobodianik attracts others, but more on that later.

- Piano music in the Ozon online store →

Slobodyanyk began his regular training in Lviv. His father, a famous doctor, was fond of music from a young age, at one time he was even the first violin of a symphony orchestra. The mother was not bad at the piano, and she taught her son the first lessons in playing this instrument. Then the boy was sent to a music school, to Lydia Veniaminovna Galembo. There he quickly drew attention to himself: at the age of fourteen he played in the hall of the Lviv Philharmonic Beethoven’s Third Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, and later performed with a solo clavier band. He was transferred to Moscow, to the Central Ten-Year Music School. For some time he was in the class of Sergei Leonidovich Dizhur, a well-known Moscow musician, one of the pupils of the Neuhaus school. Then he was taken as a student by Heinrich Gustavovich Neuhaus himself.

With Neuhaus, Slobodyanik’s classes, one might say, did not work out, although he stayed near the famous teacher for about six years. “It didn’t work out, of course, solely through my fault,” says the pianist, “which I never cease to regret to this day.” The Slobodyannik (to be honest) never belonged to those who have a reputation for being organized, collected, able to keep themselves within the iron framework of self-discipline. He studied unevenly in his youth, according to his mood; his early successes came much more from a rich natural talent than from systematic and purposeful work. Neuhaus was not surprised by his talent. Capable young people around him were always in abundance. “The greater the talent,” he repeated more than once in his circle, “the more legitimate the demand for early responsibility and independence” (Neigauz G. G. On the art of piano playing. – M., 1958. P. 195.). With all his energy and vehemence, he rebelled against what later, returning in thought to Slobodyanik, he diplomatically called “failure to fulfill various duties” (Neigauz G. G. Reflections, memories, diaries. S. 114.).

Slobodyanik himself honestly admits that, it should be noted, he is generally extremely straightforward and sincere in self-assessments. “I, how to put it more delicately, was not always properly prepared for the lessons with Genrikh Gustavovich. What can I say now in my defense? Moscow after Lvov captivated me with many new and powerful impressions… It turned my head with bright, seemingly extraordinarily tempting attributes of metropolitan life. I was fascinated by many things – often to the detriment of work.

In the end, he had to part with Neuhaus. Nevertheless, the memory of a wonderful musician is still dear to him today: “There are people who simply cannot be forgotten. They are with you always, for the rest of your life. It is rightly said: an artist is alive as long as he is remembered… By the way, I felt the influence of Henry Gustavovich for a very long time, even when I was no longer in his class.”

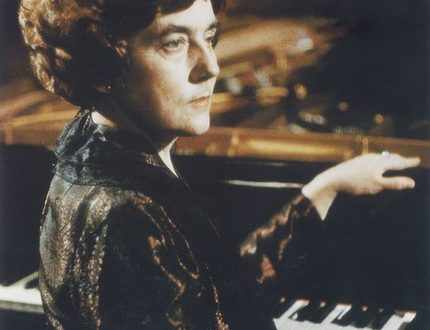

Slobodyanik graduated from the conservatory, and then graduate school, under the guidance of a student of Neuhaus – Vera Vasilievna Gornostaeva. “A magnificent musician,” he says of his last teacher, “subtle, insightful… A man of sophisticated spiritual culture. And what was especially important for me was an excellent organizer: I owe her will and energy no less than her mind. Vera Vasilievna helped me find myself in musical performance.”

With the help of Gornostaeva, Slobodyanik successfully completed the competitive season. Even earlier, during his studies, he was awarded prizes and diplomas at competitions in Warsaw, Brussels, and Prague. In 1966, he made his last appearance at the Third Tchaikovsky Competition. And he was awarded an honorary fourth prize. The period of his apprenticeship ended, the everyday life of a professional concert performer began.

… So, what are the qualities of Slobodianik that attract the public? If you look at “his” press from the beginning of the sixties to the present, the abundance of such characteristics in it as “emotional richness”, “fullness of feelings”, “spontaneity of artistic experience”, etc. is involuntarily striking. , not so rare, found in many reviews and music-critical reviews. At the same time, it is difficult to condemn the authors of the materials about Slobodyanyk. It would be very difficult to choose another, talking about him.

Indeed, Slobodyanik at the piano is the fullness and generosity of artistic experience, spontaneity of will, a sharp and strong turn of passions. And no wonder. Vivid emotionality in the transmission of music is a sure sign of performing talent; Slobodian, as it was said, is an outstanding talent, nature endowed him in full, without stint.

And yet, I think, this is not just about innate musicality. Behind the high emotional intensity of Slobodyanik’s performance, the full-bloodedness and richness of his stage experiences is the ability to perceive the world in all its richness and the boundless multicolor of its colors. The ability to lively and enthusiastically respond to the environment, to make miscellanea: to see widely, to take in everything of any interest, to breathe, as they say, with a full chest … Slobodianik is generally a very spontaneous musician. Not one iota stamped, not faded over the years of his rather long stage activity. That is why listeners are attracted to his art.

It is easy and pleasant in the company of Slobodyanik – whether you meet him in the dressing room after a performance, or you watch him on stage, at the keyboard of an instrument. Some inner nobility is intuitively felt in him; “beautiful creative nature,” they wrote about Slobodyanik in one of the reviews – and with good reason. It would seem: is it possible to catch, recognize, feel these qualities (spiritual beauty, nobility) in a person who, sitting at a concert piano, plays a previously learned musical text? It turns out – it is possible. No matter what Slobodyanik puts in his programs, up to the most spectacular, winning, scenically attractive, in him as a performer one cannot notice even a shadow of narcissism. Even in those moments when you can really admire him: when he is at his best and everything he does, as they say, turns out and comes out. Nothing petty, conceited, vain can be found in his art. “With his happy stage data, there is not a hint of artistic narcissism,” those who are closely acquainted with Slobodyanik admire. That’s right, not the slightest hint. Where, in fact, does this come from: it has already been said more than once that the artist always “continues” a person, whether he wants it or not, knows about it or does not know.

He has a kind of playful style, he seems to have set a rule for himself: no matter what you do at the keyboard, everything is done slowly. Slobodyanik’s repertoire includes a number of brilliant virtuoso pieces (Liszt, Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev…); it is hard to remember that he hurried, “driven” at least one of them – as happens, and often, with piano bravura. It is no coincidence that critics reproached him sometimes for a somewhat slow pace, never for too high. This is probably how an artist should look on the stage, I think at some moments, watching him: not to lose his temper, not to lose his temper, at least in what relates to a purely external manner of behavior. Under all circumstances, be calm, with inner dignity. Even in the hottest performing moments – you never know how many of them are in the romantic music that Slobodyanik has long preferred – do not fall into exaltation, excitement, fuss … Like all extraordinary performers, Slobodyanik has a characteristic, only characteristic style games; the most accurate way, perhaps, would be to designate this style with the term Grave (slowly, majestically, significantly). It is in this manner, a little heavy in sound, outlining textured reliefs in a large and convex way, that Slobodyanik plays Brahms’ F minor sonata, Beethoven’s Fifth Concerto, Tchaikovsky’s First, Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, Myaskovsky’s sonatas. All that has now been called are the best numbers of his repertoire.

Once, in 1966, during the Third Tchaikovsky Press Competition, speaking enthusiastically about his interpretation of Rachmaninov’s concerto in D minor, she wrote: “Slobodianik plays truly in Russian.” The “Slavic intonation” is really clearly visible in him – in his nature, appearance, artistic worldview, game. It is usually not difficult for him to open up, to exhaustively express himself in the works belonging to his compatriots – especially in those inspired by images of boundless breadth and open spaces … Once one of Slobodyanik’s colleagues remarked: “There are bright, stormy, explosive temperaments. Here the temperament, rather, from the scope and breadth. The observation is correct. That is why the works of Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov are so good in the pianist, and much in the late Prokofiev. That is why (a remarkable circumstance!) he is met with such attention abroad. For foreigners, it is interesting as a typically Russian phenomenon in musical performance, as a juicy and colorful national character in art. He was warmly applauded more than once in the countries of the Old World, and many of his overseas tours were also successful.

Once in a conversation, Slobodyanik touched upon the fact that for him, as a performer, works of large forms are preferable. “In the monumental genre, I somehow feel more comfortable. Perhaps calmer than in miniature. Perhaps here the artistic instinct of self-preservation makes itself felt – there is such … If I suddenly “stumble” somewhere, “lose” something in the process of playing, then the work – I mean a large work that is far spread in the sound space – yet it will not be completely ruined. There will still be time to save him, to rehabilitate himself for an accidental error, to do something else well. If you ruin a miniature in one single place, you destroy it entirely.

He knows that at any moment he can “lose” something on the stage – this happened to him more than once, already from a young age. “Before, I had even worse. Now stage practice accumulated over the years, knowledge of one’s business help out … ”And really, which of the concert participants has not had to go astray during the game, forget, get into critical situations? Slobodyaniku, probably more often than many of the musicians of his generation. It also happened to him: as if some kind of cloud unexpectedly found on his performance, it suddenly became inert, static, internally demagnetized … And today, even when a pianist is in the prime of life, fully armed with variety experience, it happens that lively and brightly colorful fragments of music alternate at his evenings with dull, inexpressive ones. As if he loses interest in what is happening for a while, plunging into some unexpected and inexplicable trance. And then suddenly it flares up again, gets carried away, confidently leads the audience.

There was such an episode in the biography of Slobodyanik. He played in Moscow a complex and rarely performed composition by Reger – Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Bach. At first it came out of the pianist is not very interesting. It was evident that he did not succeed. Frustrated by the failure, he ended the evening by repeating Reger’s encore variations. And repeated (without exaggeration) sumptuously – bright, inspiring, hot. Clavirabend seemed to have broken up into two parts that are not much alike – this was the whole of Slobodyanik.

Is there a disadvantage now? Maybe. Who will argue: a modern artist, a professional in the high sense of the word, is obliged to manage his inspiration. Must be able to call it at will, be at least stable in your creativity. Only, speaking with all frankness, has it always been possible for each of the concert-goers, even the most widely known ones, to be able to do this? And weren’t, in spite of everything, some “unstable” artists who were by no means distinguished by their creative constancy, such as V. Sofronitsky or M. Polyakin, were the decoration and pride of the professional scene?

There are masters (in the theater, in the concert hall) who can act with the precision of impeccably adjusted automatic devices – honor and praise to them, a quality worthy of the most respectful attitude. There are others. Fluctuations in creative well-being are natural for them, like the play of chiaroscuro on a summer afternoon, like the ebb and flow of the sea, like breathing for a living organism. The magnificent connoisseur and psychologist of musical performance, G. G. Neuhaus (he already had something to say about the vagaries of stage fortune – both bright successes and failures) did not see, for example, anything reprehensible in the fact that a particular concert performer is unable to ” to produce standard products with factory accuracy – their public appearances ” (Neigauz G. G. Reflections, memories, diaries. S. 177.).

The above lists the authors with whom most of Slobodyanik’s interpretive achievements are associated – Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov, Prokofiev, Beethoven, Brahms … You can supplement this series with the names of such composers as Liszt (in Slobodyanik’s repertoire, the B-minor Sonata, the Sixth Rhapsody, Campanella, Mephisto Waltz and other Liszt pieces), Schubert (B flat major sonata), Schumann (Carnival, Symphonic Etudes), Ravel (Concerto for the left hand), Bartok (Piano Sonata, 1926), Stravinsky (“Parsley”).

Slobodianik is less convincing in Chopin, although he loves this author very much, often refers to his work – the pianist’s posters feature Chopin’s preludes, etudes, scherzos, ballads. As a rule, the 1988th century bypasses them. Scarlatti, Haydn, Mozart – these names are quite rare in the programs of his concerts. (True, in the XNUMX season Slobodyanik publicly played Mozart’s concerto in B-flat major, which he had learned shortly before. But this, in general, did not mark fundamental changes in his repertoire strategy, did not make him a “classic” pianist). Probably, the point here is in some psychological features and properties that were originally inherent in his artistic nature. But in some characteristic features of his “pianistic apparatus” – too.

He has powerful hands that can crush any performance difficulty: confident and strong chord technique, spectacular octaves, and so on. In other words, virtuosity close-up. Slobodyanik’s so-called “small equipment” looks more modest. It is felt that sometimes she lacks openwork subtlety in the drawing, lightness and grace, calligraphic chasing in details. It is possible that nature is partly to blame for this – the very structure of Slobodyanik’s hands, their pianistic “constitution”. It is possible, however, that he himself is to blame. Or rather, what G. G. Neuhaus called in his time the failure to fulfill various kinds of educational “duties”: some shortcomings and omissions from the time of early youth. It has never gone without consequences for anyone.

Slobodyanik has seen a lot in the years that he was on stage. Faced with many problems, thought about them. He is concerned that among the general public, as he believes, there is a certain decline in interest in concert life. “It seems to me that our listeners experience a certain disappointment from philharmonic evenings. Let not all listeners, but, in any case, a considerable part. Or maybe just the concert genre itself is “tired”? I don’t rule it out either.”

He does not stop thinking about what can attract the public to the Philharmonic Hall today. High class performer? Undoubtedly. But there are other circumstances, Slobodyanik believes, which do not interfere with taking into account. For example. In our dynamic time, lengthy, long-term programs are perceived with difficulty. Once upon a time, 50-60 years ago, concert artists gave evenings in three sections; now it would look like an anachronism – most likely, listeners would simply leave from the third part … Slobodyanik is convinced that concert programs these days should be more compact. No lengths! In the second half of the eighties, he had clavirabends without intermissions, in one part. “For today’s audience, listening to music for ten to an hour and fifteen minutes is more than enough. Intermission, in my opinion, is not always required. Sometimes it only dampens, distracts…”

He also thinks about some other aspects of this problem. The fact that the time has come, apparently, to make some changes in the very form, structure, organization of concert performances. It is very fruitful, according to Alexander Alexandrovich, to introduce chamber-ensemble numbers into traditional solo programs – as components. For example, pianists should unite with violinists, cellists, vocalists, etc. In principle, this enlivens philharmonic evenings, makes them more contrasting in form, more diverse in content, and thus attractive to listeners. Perhaps that is why ensemble music-making has attracted him more and more in recent years. (A phenomenon, by the way, generally characteristic of many performers at the time of creative maturity.) In 1984 and 1988, he often performed together with Liana Isakadze; they performed works for violin and piano by Beethoven, Ravel, Stravinsky, Schnittke…

Each artist has performances that are more or less ordinary, as they say, passing, and there are concerts-events, the memory of which is preserved for a long time. If speak about such Slobodyanik’s performances in the second half of the eighties, one cannot fail to mention his joint performance of Mendelssohn’s Concerto for Violin, Piano and String Orchestra (1986, accompanied by the State Chamber Orchestra of the USSR), Chausson’s Concerto for Violin, Piano and String Quartet (1985) with V. Tretyakov year, together with V. Tretyakov and the Borodin Quartet), Schnittke’s piano concerto (1986 and 1988, accompanied by the State Chamber Orchestra).

And I would like to mention one more side of his activity. Over the years, he increasingly and willingly plays in musical educational institutions – music schools, music schools, conservatories. “There, at least you know that they will listen to you really attentively, with interest, with knowledge of the matter. And they will understand what you, as a performer, wanted to say. I think this is the most important thing for an artist: to be understood. Let some critical remarks come later. Even if you don’t like something. But everything that comes out successfully, that you succeed, will also not go unnoticed.

The worst thing for a concert musician is indifference. And in special educational institutions, as a rule, there are no indifferent and indifferent people.

In my opinion, playing in music schools and music schools is something more difficult and responsible than playing in many philharmonic halls. And I personally like it. In addition, the artist is valued here, they treat him with respect, they do not force him to experience those humiliating moments that sometimes fall to his lot in relations with the administration of the philharmonic society.

Like every artist, Slobodyanik gained something over the years, but at the same time lost something else. However, his happy ability to “spontaneously ignite” during performances was still preserved. I remember once we talked with him on various topics; we talked about shadowy moments and the vicissitudes of the life of a guest performer; I asked him: is it possible, in principle, to play well, if everything around the artist pushes him to play, badly: both the hall (if you can call halls those rooms that are absolutely unsuitable for concerts, in which you sometimes have to perform), and the audience (if random and extremely few gatherings of people can be taken for a real philharmonic audience), and a broken instrument, etc., etc. “Do you know,” answered Alexander Alexandrovich, “even in these, so to speak, “unsanitary conditions” play pretty well. Yes, yes, you can, trust me. But – if only be able to enjoy music. Let this passion not come immediately, let 20-30 minutes be spent on adjusting to the situation. But then, when the music really captures you, when get turned on, – everything around becomes indifferent, unimportant. And then you can play very well … “

Well, this is the property of a real artist – to immerse himself in music so much that he stops noticing absolutely everything around him. And Slobodianik, as they said, did not lose this ability.

Surely, in the future, new joys and joys of meeting with the public await him – there will be applause, and other attributes of success that are well known to him. Only it is unlikely that this is the main thing for him today. Marina Tsvetaeva once expressed a very correct idea that when an artist enters the second half of his creative life, it becomes important for him already not success, but time…

G. Tsypin, 1990