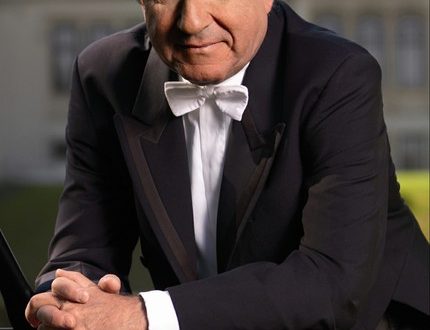

Wilhelm Backhaus |

Wilhelm Backhaus

The artistic career of one of the luminaries of world pianism began at the turn of the century. At the age of 16, he made a brilliant debut in London and in 1900 made his first tour of Europe; in 1905 he became the winner of the IV International Competition named after Anton Rubinstein in Paris; in 1910 he recorded his first records; By the beginning of the First World War, he already enjoyed considerable fame in the USA, South America, and Australia. The name and portrait of Backhaus can be seen in the Golden Book of Music published in Germany at the very beginning of our century. Doesn’t this mean, the reader may ask, that it is possible to classify Backhouse as a “modern” pianist only on formal grounds, bearing in mind the almost unprecedented length of his career, which lasted about seven decades? No, the art of Backhaus really belongs to our time, also because in his declining years the artist did not “finish his own”, but was at the top of his creative achievements. But the main thing is not even in this, but in the fact that the very style of his playing and the attitude of listeners towards him over these decades reflected many processes that are so characteristic of the development of modern pianistic art, they are like a bridge connecting the pianism of the past and our days.

Backhouse never studied at the conservatory, did not receive a systematic education. In 1892, the conductor Arthur Nikisch made this entry in an eight-year-old boy’s album: “He who plays the great Bach so excellently will surely achieve something in life.” By this time, Backhaus had just begun to take lessons from the Leipzig teacher A. Reckendorf, with whom he studied until 1899. But he considered his real spiritual father E. d’Albert, who heard him for the first time as a 13-year-old boy and for a long time helped him with friendly advice.

Backhouse entered his artistic life as a well-established musician. He quickly amassed a huge repertoire and was known as a phenomenal virtuoso capable of overcoming any technical difficulties. It was with such a reputation that he arrived in Russia at the end of 1910 and made a generally favorable impression. “The young pianist,” wrote Yu. Engel, “first of all, has exceptional piano “virtues”: a melodious (within the instrument) juicy tone; where necessary – powerful, full-sounding, without crackling and screaming forte; magnificent brush, flexibility of impact, generally amazing technique. But the most pleasant thing is the ease of this rare technique. Backhouse takes off to its heights not in the sweat of his brow, but easily, like Efimov on an airplane, so that the rise of joyful confidence is involuntarily transmitted to the listener … The second characteristic feature of Backhouse’s performance is thoughtfulness, for such a young artist at times it is simply amazing. She caught the eye from the very first piece of the program – Bach’s excellently played Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue. Everything at Backhouse is not only brilliant, but also in its place, in perfect order. Alas! – sometimes even too good! So I want to repeat Bülow’s words to one of the students: “Ai, ai, ai! So young – and already so much order! This sobriety was especially noticeable, sometimes I would be ready to say – dryness, in Chopin … One old wonderful pianist, when asked about what it takes to be a real virtuoso, answered silently, but figuratively: he pointed to his hands, head, heart. And it seems to me that Backhouse does not have complete harmony in this triad; wonderful hands, a beautiful head and a healthy, but insensitive heart that does not keep pace with them. This impression was fully shared by other reviewers. In the newspaper “Golos” one could read that “his playing lacks charm, the power of emotions: it is almost dry at times, and often this dryness, lack of feeling comes to the fore, obscuring the brilliantly virtuoso side.” “There is enough brilliance in his game, there is also musicality, but the transmission is not warmed by inner fire. A cold shine, at best, can amaze, but not captivate. His artistic conception does not always penetrate to the depths of the author’s,” we read in G. Timofeev’s review.

So, Backhouse entered the pianistic arena as an intelligent, prudent, but cold virtuoso, and this narrow-mindedness – with the richest data – prevented him from reaching true artistic heights for many decades, and at the same time, the heights of fame. Backhouse gave concerts tirelessly, he replayed almost all piano literature from Bach to Reger and Debussy, he was sometimes a resounding success – but no more. He was not even compared with the “great ones of this world” – with interpreters. Paying tribute to accuracy, accuracy, critics reproached the artist for playing everything the same way, indifferently, that he was not able to express his own attitude to the music being performed. The prominent pianist and musicologist W. Niemann noted in 1921: “An instructive example of where neoclassicism leads with its mental and spiritual indifference and increased attention to technology is the Leipzig pianist Wilhelm Backhaus … A spirit that would be able to develop a priceless gift received from nature , the spirit that would make the sound a reflection of the rich and imaginative interior, is missing. Backhouse was and remains an academic technician.” This opinion was shared by Soviet critics during the artist’s tour of the USSR in the 20s.

This went on for decades, until the early 50s. It seemed that the appearance of Backhouse remained unchanged. But implicitly, for a long time imperceptibly, there was a process of evolution of his art, closely connected with the evolution of man. The spiritual, ethical principle came to the fore more and more powerfully, wise simplicity began to prevail over external brilliance, expressiveness – over indifference. At the same time, the artist’s repertoire also changed: virtuoso pieces almost disappeared from his programs (they were now reserved for encores), Beethoven took the main place, followed by Mozart, Brahms, Schubert. And it so happened that in the 50s the public, as it were, rediscovered Backhaus, recognized him as one of the remarkable “Beethovenists” of our time.

Does this mean that the typical path has been passed from a brilliant, but empty virtuoso, of which there are many at all times, to a real artist? Not certainly in that way. The fact is that the performing principles of the artist remained unchanged throughout this path. Backhouse has always emphasized the secondary nature – from his point of view – of the art of interpreting music in relation to its creation. He saw in the artist only a “translator”, an intermediary between the composer and the listener, set as his main, if not the only goal, the exact transmission of the spirit and letter of the author’s text – without any additions from himself, without demonstrating his artistic “I”. In the years of the artist’s youth, when his pianistic and even purely musical growth significantly outpaced the development of his personality, this led to emotional dryness, impersonality, inner emptiness and other already noted shortcomings of Backhouse’s pianism. Then, as the artist matured spiritually, his personality inevitably, in spite of any declarations and calculations, began to leave an imprint on his interpretation. This in no way made his interpretation “more subjective”, did not lead to arbitrariness – here Backhouse remained true to himself; but the amazing sense of proportions, the correlation of details and the whole, the strict and majestic simplicity and spiritual purity of his art undeniably opened up, and their fusion led to democracy, accessibility, which brought him a new, qualitatively different success than before.

The best features of Backhaus come out with particular relief in his interpretation of Beethoven’s late sonatas – an interpretation cleansed of any touch of sentimentality, false pathos, entirely subordinated to the disclosure of the composer’s inner figurative structure, the richness of the composer’s thoughts. As one of the researchers noted, it sometimes seemed to the listeners of Backhouse that he was like a conductor who lowered his hands and gave the orchestra the opportunity to play on its own. “When Backhaus plays Beethoven, Beethoven speaks to us, not Backhaus,” wrote the famous Austrian musicologist K. Blaukopf. Not only late Beethoven, but also Mozart, Haydn, Brahms, Schubert. Schumann found in this artist a truly outstanding interpreter, who at the end of his life combined virtuosity with wisdom.

In fairness, it should be emphasized that even in his later years – and they were the heyday for Backhouse – he did not succeed in everything equally. His manner turned out to be less organic, for example, when applied to Beethoven’s music of the early and even middle period, where more warmth of feeling and fantasy is required from the performer. One reviewer remarked that “where Beethoven says less, Backhouse has almost nothing to say.”

At the same time, time has also allowed us to take a fresh look at the art of Backhaus. It became clear that his “objectivism” was a kind of reaction to the general fascination with romantic and even “super-romantic” performance, characteristic of the period between the two world wars. And, perhaps, it was after this enthusiasm began to wane that we were able to appreciate a lot of things in Backhouse. So one of the German magazines was hardly right in calling Backhaus in an obituary “the last of the great pianists of a bygone era.” Rather, he was one of the first pianists of the present era.

“I would like to play music until the last days of my life,” said Backhouse. His dream came true. The last decade and a half have become a period of unprecedented creative upsurge in the artist’s life. He celebrated his 70th birthday with a big trip to the USA (repeating it two years later); in 1957 he played all of Beethoven’s concertos in Rome in two evenings. Having then interrupted his activity for two years (“to put the technique in order”), the artist again appeared before the public in all his splendor. Not only at concerts, but also during rehearsals, he never played half-heartedly, but, on the contrary, always demanded optimal tempos from conductors. He considered it a matter of honor until his last days to have in reserve, for encores, at the ready such difficult plays as Liszt’s Campanella or Liszt’s transcriptions of Schubert’s songs. In the 60s, more and more recordings of Backhouse were released; the records of this time captured his interpretation of all the sonatas and concertos of Beethoven, the works of Haydn, Mozart and Brahms. On the eve of his 85th birthday, the artist played with great enthusiasm in Vienna the Second Brahms Concerto, which he first performed in 1903 with H. Richter. Finally, 8 days before his death, he gave a concert at the Carinthian Summer festival in Ostia and again played, as always, superbly. But a sudden heart attack prevented him from finishing the program, and a few days later the wonderful artist died.

Wilhelm Backhaus did not leave school. He did not like and did not want to teach. Few attempts – at King’s College in Manchester (1905), the Sonderhausen Conservatory (1907), the Philadelphia Curtis Institute (1925 – 1926) did not leave a trace in his biography. He had no students. “I am too busy for this,” he said. “If I have time, Backhouse himself becomes my favorite student.” He said it without posture, without coquetry. And he strived for perfection until the end of his life, learning from music.

Grigoriev L., Platek Ya.