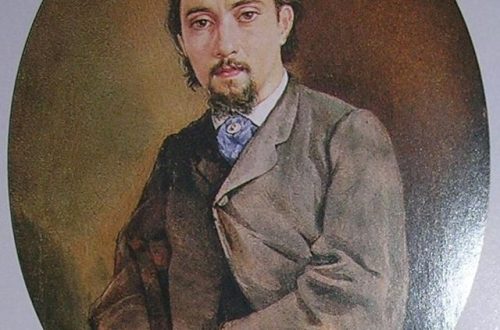

Senezino (Senezino) |

Senesino

At the head of the opera house of the 1650th century were the prima donna (“prima donna”) and the castrato (“primo uomo”). Historically, traces of the use of castrati as singers date back to the last two decades of the XNUMXth century, and they began their incursion into opera around XNUMX. However, Monteverdi and Cavalli in their first operatic works still used the services of four natural singing voices. But the real flowering of the art of castrati reached in the Neapolitan opera.

Castration of young men, in order to make them singers, has probably always existed. But it was only with the birth of polyphony and opera in the 1588th and XNUMXth centuries that castrati became necessary in Europe as well. The immediate reason for this was the XNUMX papal ban on women singing in church choirs, as well as performing on theater stages in the papal states. Boys were used to perform female alto and soprano parts.

But at the age when the voice breaks down, and at that time they are already becoming experienced singers, the timbre of the voice loses its clarity and purity. To prevent this from happening, in Italy, as well as in Spain, boys were castrated. The operation stopped the development of the larynx, preserving for life a real voice – alto or soprano. In the meantime, the ribcage continued to develop, and even more than in ordinary young people, thus, castrati had a much larger volume of exhaled air than even women with a soprano voice. The strength and purity of their voices cannot be compared with the current ones, even if they are high voices.

The operation was performed on boys usually between the ages of eight and thirteen. Since such operations were forbidden, they were always done under the pretext of some illness or accident. The child was dipped in a bath of warm milk, given a dose of opium to ease the pain. The male genitalia were not removed, as practiced in the East, but the testicles were cut and emptied. Young people became infertile, but with a quality operation they were not impotent.

The castrati were mocked to their hearts’ content in literature, and mainly in the buffoon opera, which excelled with might and main. These attacks, however, did not refer to their singing art, but mainly to their outward bearing, effeminacy and an increasingly unbearable swagger. The singing of the castrati, which perfectly combined the timbre of a boyish voice and the strength of the lungs of an adult man, was still praised as the pinnacle of all singing achievements. The main performers at a considerable distance from them were followed by artists of the second rank: one or more tenors and female voices. The prima donna and the castrato made sure that these singers did not get too big and especially too grateful roles. Male basses gradually disappeared from serious opera as early as Venetian times.

A number of Italian opera singers-castrates have reached a high perfection in the vocal and performing arts. Among the great “Muziko” and “Wonder”, as castrato singers were called in Italy, are Caffarelli, Carestini, Guadagni, Pacciarotti, Rogini, Velluti, Cresentini. Among the first it is necessary to note Senesino.

The estimated date of birth of Senesino (real name Fratesco Bernard) is 1680. However, it is highly likely that he is actually younger. Such a conclusion can be drawn from the fact that his name is mentioned in the lists of performers only from 1714. Then in Venice, he sang in “Semiramide” by Pollarolo Sr. He began to study the singing of Senesino in Bologna.

In 1715, the impresario Zambekkari writes about the manner of the singer’s performance:

“Senesino still behaves strangely, he stands motionless like a statue, and if sometimes he makes some kind of gesture, then it is exactly the opposite of what is expected. His recitatives are as terrible as Nicolini’s were beautiful, and as for the arias, he performs them well if he happens to be in the voice. But last night, in the best aria, he went two bars ahead.

Casati is absolutely unbearable, and because of his boring pathetic singing, and because of his exorbitant pride, he has teamed up with Senesino, and they have no respect for anyone. Therefore, no one can see them, and almost all Neapolitans consider them (if they are thought of at all) as a pair of self-righteous eunuchs. They never sang with me, unlike most operatic castrati who performed in Naples; only these two I never invited. And now I can take comfort in the fact that everyone treats them badly.

In 1719, Senesino sings at the court theater in Dresden. A year later, the famous composer Handel came here to recruit performers for the Royal Academy of Music, which he had created in London. Together with Senesino, Berenstadt and Margherita Durastanti also went to the shores of the “foggy Albion”.

Senesino stayed in England for a long time. He sang with great success at the academy, singing leading roles in all operas by Bononcini, Ariosti, and above all by Handel. Although in fairness it must be said that the relationship between the singer and the composer was not the best. Senesino became the first performer of the main parts in a number of Handel’s operas: Otto and Flavius (1723), Julius Caesar (1724), Rodelinda (1725), Scipio (1726), Admetus (1727) ), “Cyrus” and “Ptolemy” (1728).

On May 5, 1726, the premiere of Handel’s opera Alexander took place, which was a great success. Senesino, who played the title role, was at the pinnacle of fame. Success was shared with him by two prima donnas – Cuzzoni and Bordoni. Unfortunately, the British have formed two camps of irreconcilable admirers of prima donnas. Senesino was tired of the strife of the singers, and, having said he was sick, he went to his homeland – to Italy. Already after the collapse of the academy, in 1729, Handel himself came to Senesino to ask him to return.

So, despite all the disagreements, Senesino, starting in 1730, began to perform in a small troupe organized by Handel. He sang in two of the composer’s new works, Aetius (1732) and Orlando (1733). However, the contradictions turned out to be too deep and in 1733 there was a final break.

As subsequent events showed, this quarrel had far-reaching consequences. She became one of the main reasons why, in opposition to Handel’s troupe, the “Opera of the nobility” was created, headed by N. Porpora. Together with Senesino, another outstanding “muziko” – Farinelli sang here. Contrary to expectations, they got along well. Perhaps the reason is that Farinelli is a sopranist, while Senesino has a contralto. Or perhaps Senesino simply sincerely admired the skill of a younger colleague. In favor of the second is the story that happened in 1734 at the premiere of A. Hasse’s opera “Artaxerxes” at the Royal Theater in London.

In this opera, Senesino sang for the first time with Farinelli: he played the role of an angry tyrant, and Farinelli – an unfortunate hero chained. However, with his very first aria, he so touched the hardened heart of the enraged tyrant that Senesino, forgetting his role, ran up to Farinelli and embraced him.

Here is the opinion of the composer I.-I. Quantz who heard the singer in England:

“He had a powerful, clear and pleasant contralto, with excellent intonation and excellent trills. His manner of singing was masterful, his expressiveness knew no equal. Without overloading the adagio with ornaments, he sang the main notes with incredible refinement. His allegroes were full of fire, with clear and fast caesuras, they came from the chest, he performed them with good articulation and pleasant manners. He behaved well on stage, all his gestures were natural and noble.

All these qualities were complemented by a majestic figure; his appearance and demeanor were more suited to the party of a hero than to a lover.”

The rivalry between the two opera houses ended in the collapse of both in 1737. After that Senesino returned to Italy.

The most famous castrati received very large fees. Say, in the 30s in Naples, a famous singer received from 600 to 800 Spanish doubloons per season. The amount could have increased significantly due to deductions from benefit performances. It was 800 doubloons, or 3693 ducats, that Senesino, who sang in 1738/39 at the San Carlo Theater, received here for the season.

Surprisingly, local listeners reacted to the singer’s performances without due reverence. Senesino’s engagement was not renewed the following season. This surprised such a connoisseur of music as de Brosse: “The great Senesino performed the main part, I was fascinated by the taste of his singing and playing. However, I noticed with surprise that his countrymen were not pleased. They complain that he sings in the old style. Here is proof that here musical tastes change every ten years.”

From Naples, the singer returns to his native Tuscany. His last performances, apparently, took place in two operas by Orlandini – “Arsaces” and “Ariadne”.

Senesino died in 1750.