Pablo de Sarasate |

Paul of Sarasate

Sarasate. Andalusian Romance →

Sarasate is phenomenal. The way his violin sounds is the way it has never been sounded by anyone. L. Auer

The Spanish violinist and composer P. Sarasate was a brilliant representative of the ever-living, virtuoso art. “Paganini of the end of the century, the king of the art of cadence, a sunny bright artist,” was what Sarasate was called by his contemporaries. Even the principal opponents of virtuosity in art, I. Joachim and L. Auer, bowed before his remarkable instrumentalism. Sarasate was born into the family of a military bandmaster. Glory accompanied him truly from the first steps of his artistic career. Already at the age of 8 he gave his first concerts in La Coruña and then in Madrid. The Spanish Queen Isabella, admiring the talent of the little musician, awarded Sarasate with an A. Stradivari violin and provided him with a scholarship to study at the Paris Conservatory.

Only one year of studies in the class of D. Alar was enough for the thirteen-year-old violinist to graduate from one of the best conservatories in the world with a gold medal. However, feeling the need to deepen his musical and theoretical knowledge, he studied composition for another 2 years. After completing his education, Sarasate makes many concert trips to Europe and Asia. Twice (1867-70, 1889-90) he undertook a large concert tour of the countries of North and South America. Sarasate has repeatedly visited Russia. Close creative and friendly ties connected him with Russian musicians: P. Tchaikovsky, L. Auer, K. Davydov, A. Verzhbilovich, A. Rubinshtein. About a joint concert with the latter in 1881, the Russian musical press wrote: “Sarasate is as incomparable in playing the violin as Rubinstein has no rivals in the field of piano playing …”

Contemporaries saw the secret of Sarasate’s creative and personal charm in the almost childish immediacy of his worldview. According to the recollections of friends, Sarasate was a simple-hearted man, passionately fond of collecting canes, snuff boxes, and other antique gizmos. Subsequently, the musician transferred the entire collection he had collected to his hometown of Pamplrne. The clear, cheerful art of the Spanish virtuoso has captivated listeners for almost half a century. His playing attracted with a special melodious-silver sound of the violin, exceptional virtuoso perfection, enchanting lightness and, in addition, romantic elation, poetry, nobility of phrasing. The violinist’s repertoire was exceptionally extensive. But with the greatest success, he performed his own compositions: “Spanish Dances”, “Basque Capriccio”, “Aragonese Hunt”, “Andalusian Serenade”, “Navarra”, “Habanera”, “Zapateado”, “Malagueña”, the famous “Gypsy Melodies” . In these compositions, the national features of Sarasate’s composing and performing style were especially vividly manifested: rhythmic originality, coloristic sound production, subtle implementation of the traditions of folk art. All these works, as well as the two great concert fantasies Faust and Carmen (on the themes of the operas of the same name by Ch. Gounod and G. Bizet), still remain in the violinists’ repertoire. The works of Sarasate left a significant mark on the history of Spanish instrumental music, having a significant impact on the work of I. Albeniz, M. de Falla, E. Granados.

Many major composers of that time dedicated their works to Sarasata. It was with his performance in mind that such masterpieces of violin music were created as the Introduction and Rondo-Capriccioso, “Havanese” and the Third Violin Concerto by C. Saint-Saens, “Spanish Symphony” by E. Lalo, the Second Violin Concerto and “Scottish Fantasy” M Bruch, concert suite by I. Raff. G. Wieniawski (Second Violin Concerto), A. Dvorak (Mazurek), K. Goldmark and A. Mackenzie dedicated their works to the outstanding Spanish musician. “The greatest significance of Sarasate,” Auer noted in this connection, “is based on the wide recognition that he won with his performance of the outstanding violin works of his era.” This is the great merit of Sarasate, one of the most progressive aspects of the performance of the great Spanish virtuoso.

I. Vetlitsyna

Virtuoso art never dies. Even in the era of the highest triumph of artistic trends, there are always musicians who captivate with “pure” virtuosity. Sarasate was one of them. “Paganini of the end of the century”, “the king of the art of cadence”, “sunny-bright artist” – this is how contemporaries called Sarasate. Before his virtuosity, remarkable instrumentalism bowed even those who fundamentally rejected virtuosity in art – Joachim, Auer.

Sarasate conquered everyone. The secret of his charm lay in the almost childish immediacy of his art. They “do not get angry” with such artists, their music is accepted as the singing of birds, as the sounds of nature – the sound of the forest, the murmur of the stream. Unless there can be claims to a nightingale? He sings! So is Sarasate. He sang on the violin – and the audience froze with delight; he “painted” colorful pictures of Spanish folk dances – and they appeared in the imagination of the listeners as alive.

Auer ranked Sarasate (after Viettan and Joachim) above all the violinists of the second half of the XNUMXth century. In Sarasate’s game, he was surprised by the extraordinary lightness, naturalness, ease of his technical apparatus. “One evening,” I. Nalbandian writes in his memoirs, “I asked Auer to tell me about Sarasat. Leopold Semyonovich got up from the sofa, looked at me for a long time and said: Sarasate is a phenomenal phenomenon. The way his violin sounds is the way it has never been sounded by anyone. In Sarasate’s playing, you can’t hear the “kitchen” at all, no hair, no rosin, no bow changes and no work, tension – he plays everything jokingly, and everything sounds perfect with him … ”Sending Nalbandian to Berlin, Auer advised him to take advantage of any opportunity, to listen to Sarasate, and if the opportunity presents itself, to play the violin for him. Nalbandian adds that at the same time, Auer handed him a letter of recommendation, with a very laconic address on the envelope: “Europe – Sarasate.” And that was enough.

“Upon my return to Russia,” Nalbandian continues, “I made a detailed report to Auer, to which he said: “You see what benefit your trip abroad has brought you. You have heard the highest examples of the performance of classical works by the great musicians-artists Joachim and Sarasate – the highest virtuoso perfection, the phenomenal phenomenon of violin playing. What a lucky man Sarasate is, not like we are violin slaves who have to work every day, and he lives for his own pleasure. And he added: “Why should he play when everything is already working out for him?” Having said this, Auer looked sadly at his hands and sighed. Auer had “ungrateful” hands and had to work hard every day to keep the technique.”

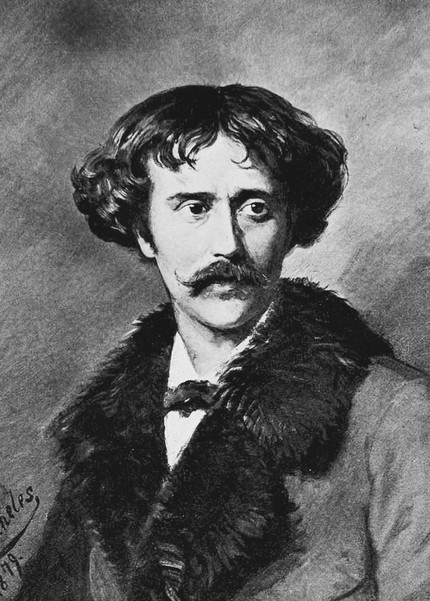

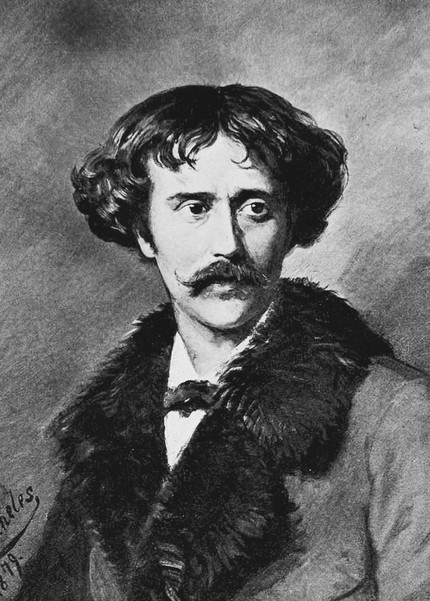

“The name Sarasate was magical for violinists,” writes K. Flesh. – With reverence, as if it were some phenomenon from a wonderland, we boys (this was in 1886) looked at the little black-eyed Spaniard – with carefully trimmed jet-black mustaches and the same curly, curly, carefully combed hair . This little man stepped onto the stage with long strides, with true Spanish grandeur, outwardly calm, even phlegmatic. And then he began to play with unheard-of freedom, with speed brought to the limit, bringing the audience into the greatest delight.

Sarasate’s life turned out to be extremely happy. He was in the full sense of the word a favorite and minion of fate.

“I was born,” he writes, “on March 14, 1844, in Pamplona, the main city of the province of Navarre. My father was a military conductor. I learned to play the violin from an early age. When I was only 5 years old, I already played in the presence of Queen Isabella. The king liked my performance and he gave me a pension, which allowed me to go to Paris to study.

Judging by other biographies of Sarasate, this information is not accurate. He was born not on March 14, but on March 10, 1844. At birth, he was named Martin Meliton, but he took the name Pablo himself later, while living in Paris.

His father, a Basque by nationality, was a good musician. Initially, he himself taught his son the violin. At the age of 8, the child prodigy gave a concert in La Coruna and his talent was so obvious that his father decided to take him to Madrid. Here he gave the boy to study Rodriguez Saez.

When the violinist was 10 years old, he was shown at court. The game of little Sarasate made a stunning impression. He received a beautiful Stradivarius violin from Queen Isabella as a gift, and the court of Madrid took over the costs of his further education.

In 1856, Sarasate was sent to Paris, where he was accepted into his class by one of the outstanding representatives of the French violin school, Delphine Alar. Nine months later (almost unbelievably!) he completed the full course of the conservatory and won the first prize.

Obviously, the young violinist came to Alar already with a sufficiently developed technique, otherwise his lightning-fast graduation from the conservatory cannot be explained. However, after graduating from it in the violin class, he stayed in Paris for another 6 years to study music theory, harmony and other areas of art. Only in the seventeenth year of his life Sarasate left the Paris Conservatory. From this time begins his life as an itinerant concert performer.

Initially, he went on an extended tour of the Americas. It was organized by the wealthy merchant Otto Goldschmidt, who lived in Mexico. An excellent pianist, in addition to the functions of an impresario, he took on the duties of an accompanist. The trip was financially successful, and Goldschmidt became Sarasate’s impresario for life.

After America, Sarasate returned to Europe and quickly gained fantastic popularity here. His concerts in all European countries are held in triumph, and in his homeland he becomes a national hero. In 1880, in Barcelona, Sarasate’s enthusiastic admirers staged a torchlight procession attended by 2000 people. Railway societies in Spain provided entire trains for his use. He came to Pamplona almost every year, the townspeople arranged for him pompous meetings, headed by the municipality. In honor of him, bullfights were always given, Sarasate responded to all these honors with concerts in favor of the poor. True, once (in 1900) the festivities on the occasion of the arrival of Sarasate in Pamplona almost turned out to be disrupted. The newly elected mayor of the city tried to cancel them for political reasons. He was a monarchist, and Sarasate was known as a democrat. The mayor’s intentions caused outrage. “The newspapers intervened. And the defeated municipality, together with its head, was forced to resign. The case is perhaps the only one of its kind.

Sarasate has visited Russia many times. For the first time, in 1869, he visited only Odessa; for the second time – in 1879 he toured in St. Petersburg and Moscow.

Here is what L. Auer wrote: “One of the most interesting among the famous foreigners invited by the Society (meaning the Russian Musical Society. – L. R.) was Pablo de Sarasate, then still a young musician who came to us after his early brilliant success in Germany. I saw and heard him for the first time. He was small, thin, but at the same time very graceful, with a beautiful head, with black hair parted in the middle, according to the fashion of that time. As a deviation from the general rule, he wore on his chest a large ribbon with a star of the Spanish order he had received. This was news to everyone, since usually only princes of the blood and ministers appeared in such decorations at official receptions.

The very first notes he extracted from his Stradivarius – alas, now mute and forever buried in the Madrid Museum! – made a strong impression on me with the beauty and crystalline purity of tone. Possessing remarkable technique, he played without any tension, as if barely touching the strings with his magical bow. It was hard to believe that these wonderful sounds, caressing the ear, like the voice of the young Adeline Patty, could come from such grossly material things as hair and strings. The listeners were in awe and, of course, Sarasate was an extraordinary success.

“In the midst of his St. Petersburg triumphs,” Auer writes further, “Pablo de Sarasate remained a good comrade, preferring the company of his musical friends to performances in rich houses, where he received from two to three thousand francs per evening – an extremely high fee for that time. Free evenings. he spent with Davydov, Leshetsky or with me, always cheerful, smiling and in a good mood, extremely happy when he managed to win a few rubles from us at cards. He was very gallant with the ladies and always carried with him several small Spanish fans, which he used to give them as a keepsake.

Russia conquered Sarasate with its hospitality. After 2 years, he again gives a series of concerts here. After the first concert, which took place on November 28, 1881 in St. Petersburg, in which Sarasate performed together with A. Rubinstein, the musical press noted: Sarasate “is as incomparable in playing the violin as the first (i.e., Rubinstein. – L. R. ) has no rivals in the field of piano playing, with the exception, of course, of Liszt.

The arrival of Sarasate in St. Petersburg in January 1898 was again marked by a triumph. An innumerable crowd of the public filled the hall of the Noble Assembly (the current Philharmonic). Together with Auer, Sarasate gave a quartet evening where he performed Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata.

The last time Petersburg listened to Sarasate was already on the slope of his life, in 1903, and press reviews indicate that he retained his virtuoso skills until old age. “The outstanding qualities of the artist are the juicy, full and strong tone of his violin, the brilliant technique that overcomes all sorts of difficulties; and, conversely, a light, gentle and melodious bow in plays of a more intimate nature – all this is perfectly mastered by the Spaniard. Sarasate is still the same “king of violinists”, in the accepted sense of the word. Despite his old age, he still surprises with his liveliness and ease of everything he performs.

Sarasate was a unique phenomenon. For his contemporaries, he opened up new horizons for violin playing: “Once in Amsterdam,” writes K. Flesh, “Izai, while talking with me, gave the following assessment to Sarasata: “It was he who taught us to play cleanly.” The desire of modern violinists for technical perfection, precision and infallibility of playing comes from Sarasate from the time of his appearance on the concert stage. Before him, freedom, fluidity and brilliance of performance were considered more important.

“… He was a representative of a new type of violinist and played with amazing technical ease, without the slightest tension. His fingertips landed on the fretboard quite naturally and calmly, without hitting the strings. The vibration was much wider than was customary with violinists before Sarasate. He rightly believed that the possession of the bow is the first and most important means of extracting the ideal – in his opinion – tone. The “blow” of his bow on the string hit exactly in the center between the extreme points of the bridge and the fretboard of the violin and hardly ever approached the bridge, where, as we know, one can extract a characteristic sound similar in tension to the sound of an oboe.

The German historian of violin art A. Moser also analyzes Sarasate’s performance skills: “When asked by what means Sarasate achieved such a phenomenal success,” he writes, “we should first of all answer with sound. His tone, without any “impurities”, full of “sweetness”, acted when he began to play, directly stunning. I say “started playing” not without intent, since the sound of Sarasate, despite all its beauty, was monotonous, almost incapable of change, due to which, after a while, what is called “got bored”, like constant sunny weather in nature. The second factor that contributed to Sarasate’s success was the absolutely incredible ease, the freedom with which he used his colossal technique. He intoned unmistakably cleanly and overcame the highest difficulties with exceptional grace.

A number of information about the technical elements of the game Sarasate provides Auer. He writes that Sarasate (and Wieniawski) “possessed a swift and precise, extremely long trill, which was an excellent confirmation of their technical mastery.” Elsewhere in the same book by Auer we read: “Sarasate, who had a dazzling tone, used only staccato volant (that is, flying staccato. – L.R.), not very fast, but infinitely graceful. The last feature, that is, grace, illuminated his entire game and was complemented by an exceptionally melodious sound, but not too strong. Comparing the manner of holding the bow of Joachim, Wieniawski and Sarasate, Auer writes: “Sarasate held the bow with all his fingers, which did not prevent him from developing a free, melodious tone and airy lightness in the passages.”

Most reviews note that the classics were not given to Sarasata, although he often and often turned to the works of Bach, Beethoven, and liked to play in quartets. Moser says that after the first performance of the Beethoven Concerto in Berlin in the 80s, a review by music critic E. Taubert followed, in which Sarasate’s interpretation was rather sharply criticized in comparison with Joachim’s. “The next day, meeting with me, an enraged Sarasate shouted to me: “Of course, in Germany they believe that someone who performs a Beethoven Concerto must sweat like your fat maestro!”

Reassuring him, I noticed that I was indignant when the audience, delighted with his playing, interrupted the orchestral tutti with applause after the first solo. Sarasate lashed out at me, “Dear man, don’t talk such nonsense! Orchestral tutti exist to give the soloist a chance to rest and the audience to applaud.” When I shook my head, taken aback by such childish judgment, he continued: “Leave me alone with your symphonic works. You ask why I don’t play the Brahms Concerto! I don’t want to deny at all that this is pretty good music. But do you really consider me so devoid of taste that I, having stepped onto the stage with a violin in my hands, stood and listened to how in the Adagio the oboe plays the only melody of the whole work to the audience?

Moser and Sarasate’s chamber music-making are vividly described: “During longer stays in Berlin, Sarasate used to invite my Spanish friends and classmates E. F. Arbos (violin) and Augustino Rubio to his hotel Kaiserhof to play a quartet with me. (cello). He himself played the part of the first violin, Arbos and I alternately played the part of the viola and the second violin. His favorite quartets were, along with Op. 59 Beethoven, Schumann and Brahms quartets. These are the ones that were most often performed. Sarasate played extremely diligently, fulfilling all the composer’s instructions. It sounded great, of course, but the “inner” that was “between the lines” remained unrevealed.”

Moser’s words and his assessments of the nature of Sarasate’s interpretation of classical works find confirmation in articles and other reviewers. It is often pointed out the monotony, monotony that distinguished the sound of Sarasate’s violin, and the fact that the works of Beethoven and Bach did not work out well for him. However, Moser’s characterization is still one-sided. In works close to his personality, Sarasate showed himself to be a subtle artist. According to all reviews, for example, he performed Mendelssohn’s concerto incomparably. And how badly were the works of Bach and Beethoven performed, if such a strict connoisseur as Auer spoke positively about Sarasate’s interpretive art!

“Between 1870 and 1880, the tendency to perform highly artistic music in public concerts grew so much, and this principle received such universal recognition and support from the press, that this prompted eminent virtuosos like Wieniawski and Sarasate – the most remarkable representatives of this trend – to widely use in their concertos violin compositions of the highest type. They included Bach’s Chaconne and other works, as well as Beethoven’s Concerto, in their programs, and with the most pronounced individuality of interpretation (I mean individuality in the best sense of the word), their truly artistic interpretation and adequate performance contributed a lot to their fame. “.

Regarding Sarasate’s interpretation of Saint-Saens’s Third Concerto dedicated to him, the author himself wrote: “I wrote a concerto in which the first and last parts are very expressive; they are separated by a part where everything breathes tranquility – like a lake between mountains. The great violinists who did me the honor of playing this work usually did not understand this contrast – they vibrated on the lake, just like in the mountains. Sarasate, for whom the concerto was written, was as calm on the lake as he was excited in the mountains. And then the composer concludes: “There is nothing better when performing music, how to convey its character.”

In addition to the concerto, Saint-Saëns dedicated the Rondo Capriccioso to Sarasata. Other composers expressed their admiration for the violinist’s performance in the same way. He was dedicated to: the First Concerto and the Spanish Symphony by E. Lalo, the Second Concerto and the Scottish Fantasy by M. Bruch, the Second Concerto by G. Wieniawski. “The greatest importance of Sarasate,” Auer argued, “is based on the wide recognition that he won for his performance of the outstanding violin works of his era. It is also his merit that he was the first to popularize the concertos of Bruch, Lalo and Saint-Saens.

Best of all, Sarasate conveyed virtuoso music and his own works. In them he was incomparable. Of his compositions, Spanish dances, Gypsy tunes, Fantasia on motifs from the opera “Carmen” by Bizet, Introduction and tarantella have gained great fame. The most positive and closest to the truth assessment of Sarasate the composer was given by Auer. He wrote: “The original, talented and truly concert pieces of Sarasate himself – “Airs Espagnoles”, so brightly colored by the fiery romance of his native country – are without a doubt the most valuable contribution to the violin repertoire.”

In Spanish dances, Sarasate created colorful instrumental adaptations of tunes native to him, and they are done with a delicate taste, grace. From them – a direct path to the miniatures of Granados, Albeniz, de Falla. Fantasy on motifs from Bizet’s “Carmen” is perhaps the best in world violin literature in the genre of virtuoso fantasies chosen by the composer. It can safely be put on a par with the most vivid fantasies of Paganini, Venyavsky, Ernst.

Sarasate was the first violinist whose playing was recorded on gramophone records; he performed the Prelude from the E-major partita by J.-S. Bach for violin solo, as well as an Introduction and a tarantella of his own composition.

Sarasate had no family and in fact devoted his entire life to the violin. True, he had a passion for collecting. The objects in his collections were quite amusing. Sarasate and in this passion seemed like a big child. He was fond of collecting … walking sticks (!); collected canes, decorated with gold knobs and inlaid with precious stones, valuable antiquities and antique gizmos. He left behind a fortune estimated at 3000000 francs.

Sarasate died in Biarritz on September 20, 1908, at the age of 64. All that he acquired, he bequeathed mainly to artistic and charitable organizations. The Paris and Madrid Conservatories each received 10 francs; in addition, each of them is a Stradivarius violin. A large amount was earmarked for awards to musicians. Sarasate donated his wonderful art collection to his hometown of Pamplona.

L. Raaben