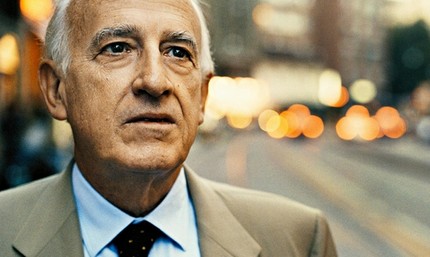

Maurizio Pollini (Maurizio Pollini) |

Maurizio Pollini

In the mid-70s, the press spread around the message about the results of a survey conducted among the world’s leading music critics. They were allegedly asked one single question: who do they consider the best pianist of our time? And by an overwhelming majority (eight votes out of ten), the palm was given to Maurizio Pollini. Then, however, they began to say that it was not about the best, but only about the most successful recording pianist of all (and this significantly changes the matter); but one way or another, the name of the young Italian artist was first on the list, which included only the luminaries of the world pianistic art, and by age and experience far exceeded him. And although the senselessness of such questionnaires and the establishment of a “table of ranks” in art is obvious, this fact speaks volumes. Today it is clear that Mauritsno Pollini has firmly entered the ranks of the elect … And he entered quite a long time ago – around the beginning of the 70s.

- Piano music in the Ozon online store →

However, the scale of Pollini’s artistic and pianistic talent was obvious to many even earlier. It is said that in 1960, when a very young Italian, ahead of almost 80 rivals, became the winner of the Chopin Competition in Warsaw, Arthur Rubinstein (one of those whose names were on the list) exclaimed: “He already plays better than any of us – jury members! Perhaps never before in the history of this competition – neither before nor after – have the audience and the jury been so united in their reaction to the winner’s game.

Only one person, as it turned out, did not share such enthusiasm – it was Pollini himself. In any case, he did not seem to be going to “develop success” and take advantage of the widest opportunities that an undivided victory opened up for him. Having played several concerts in different cities of Europe and recorded one disc (Chopin’s E-minor Concerto), he refused lucrative contracts and big tours, and then stopped performing altogether, bluntly stating that he did not feel ready for a concert career.

This turn of events caused bewilderment and disappointment. After all, the Warsaw rise of the artist was not at all unexpected – it seemed that despite his youth, he already had both sufficient training and certain experience.

The son of an architect from Milan was not a child prodigy, but early showed a rare musicality and from the age of 11 he studied at the conservatory under the guidance of prominent teachers C. Lonati and C. Vidusso, had two second prizes at the International Competition in Geneva (1957 and 1958) and the first – at the competition named after E. Pozzoli in Seregno (1959). Compatriots, who saw in him the successor to Benedetti Michelangeli, were now clearly disappointed. However, in this step, the most important quality of Pollini, the ability for sober introspection, a critical assessment of one’s strengths, also affected. He understood that to become a real musician, he still had a long way to go.

At the beginning of this journey, Pollini went “for training” to Benedetti Michelangeli himself. But the improvement was short-lived: in six months there were only six lessons, after which Pollini, without explaining the reasons, stopped classes. Later, when asked what these lessons gave him, he answered succinctly: “Michelangeli showed me some useful things.” And although outwardly, at first glance, in the creative method (but not in the nature of the creative individuality) both artists seem to be very close, the influence of the elder on the younger was really not significant.

For several years, Pollini did not appear on the stage, did not record; in addition to in-depth work on himself, the reason for this was a serious illness that required many months of treatment. Gradually, piano lovers began to forget about him. But when in the mid-60s the artist again met with the audience, it became clear to everyone that his deliberate (albeit partly forced) absence justified itself. A mature artist appeared before the audience, not only perfectly mastering the craft, but also knowing what and how he should say to the audience.

What is he like – this new Pollini, whose strength and originality are no longer in doubt, whose art today is the subject of not so much criticism as study? It is not so easy to answer this question. Perhaps the first thing that comes to mind when trying to determine the most characteristic features of his appearance are two epithets: universality and perfection; moreover, these qualities are inextricably merged, manifested in everything – in repertoire interests, in the boundlessness of technical possibilities, in an unmistakable stylistic flair that allows one to equally reliably interpret the most polar works in character.

Already speaking about his first recordings (made after a pause), I. Harden noted that they reflect a new stage in the development of the artist’s artistic personality. “The personal, the individual is reflected here not in particulars and extravagances, but in the creation of the whole, the flexible sensitivity of sound, in the continuous manifestation of the spiritual principle that drives each work. Pollini demonstrates a highly intelligent game, untouched by rudeness. Stravinsky’s “Petrushka” could have been played harder, rougher, more metallic; Chopin’s etudes are more romantic, more colorful, deliberately more significant, but it is difficult to imagine these works performed more soulfully. Interpretation in this case appears as an act of spiritual re-creation…”

It is in the ability to penetrate deeply into the world of the composer, to recreate his thoughts and feelings that Pollini’s unique individuality lies. It is no coincidence that many, or rather, almost all of his recordings are unanimously called reference by critics, they are perceived as examples of reading music, as its reliable “sounding editions”. This applies equally to his records and concert interpretations – the difference here is not too noticeable, because the clarity of concepts and the completeness of their implementation are almost equal in a crowded hall and in a deserted studio. This also applies to works of various forms, styles, eras – from Bach to Boulez. It is noteworthy that Pollini does not have favorite authors, any performing “specialization”, even a hint of it, is organically alien to him.

The very sequence of the release of his records speaks volumes. Chopin’s program (1968) is followed by Prokofiev’s Seventh Sonata, fragments from Stravinsky’s Petrushka, Chopin again (all etudes), then the full Schoenberg, Beethoven concertos, then Mozart, Brahms, and then Webern … As for concert programs, then there, Naturally, even more variety. Sonatas by Beethoven and Schubert, most of the compositions by Schumann and Chopin, concertos by Mozart and Brahms, music of the “New Viennese” school, even pieces by K. Stockhausen and L. Nono – such is his range. And the most captious critic has never said that he succeeds in one thing more than another, that this or that sphere is beyond the control of the pianist.

He considers the connection of times in music, in performing arts very important for himself, in many respects determining not only the nature of the repertoire and the construction of programs, but also the style of performance. His credo is as follows: “We, the interpreters, must bring the works of the classics and romantics closer to the consciousness of modern man. We must understand what classical music meant for its time. You can, say, find a dissonant chord in the music of Beethoven or Chopin: today it does not sound particularly dramatic, but at that time it was exactly like that! We just need to find a way to play the music as excitedly as it sounded back then. We have to ‘translate’ it.” Such a formulation of the question in itself completely excludes any kind of museum, abstract interpretation; yes, Pollini sees himself as an intermediary between the composer and the listener, but not as an indifferent intermediary, but as an interested one.

Pollini’s attitude to contemporary music deserves a special discussion. The artist does not simply turn to compositions created today, but fundamentally considers himself obligated to do this, and chooses what is considered difficult, unusual for the listener, sometimes controversial, and tries to reveal the true merits, lively feelings that determine the value of any music. In this regard, his interpretation of Schoenberg’s music, which Soviet listeners met, is indicative. “For me, Schoenberg has nothing to do with how he is usually painted,” says the artist (in a somewhat rough translation, this should mean “the devil is not so terrible as he is painted”). Indeed, Pollini’s “weapon of struggle” against outward dissonance becomes Pollini’s enormous timbre and dynamic diversity of the Pollinian palette, which makes it possible to discover the hidden emotional beauty in this music. The same richness of sound, the absence of mechanical dryness, which is considered almost a necessary attribute of the performance of modern music, the ability to penetrate into a complex structure, to reveal the subtext behind the text, the logic of thought are also characterized by its other interpretations.

Let’s make a reservation: some reader might think that Maurizio Pollini is really the most perfect pianist, since he has no flaws, no weaknesses, and it turns out that the critics were right, putting him in first place in the notorious questionnaire, and this questionnaire itself is only a confirmation of the prevailing the state of things. Of course it isn’t. Pollini is a wonderful pianist, and perhaps indeed the most even among the wonderful pianists, but this does not mean at all that he is the best. After all, sometimes the very absence of visible, purely human weaknesses can also turn into a disadvantage. Take, for example, his recent recordings of Brahms’ First Concerto and Beethoven’s Fourth.

Highly appreciating them, the English musicologist B. Morrison objectively noted: “There are many listeners who lack warmth and individuality in Pollini’s playing; and it’s true, he has a tendency to keep the listener at arm’s length”… Critics, for example, those familiar with his “objective” interpretation of the Schumann Concerto unanimously prefer Emil Gilels’s much hotter, emotionally rich interpretation. It is the personal, the hard-won that is sometimes lacking in his serious, deep, polished and balanced game. “Pollini’s balance, of course, has become a legend,” one of the experts noted in the mid-70s, “but it is becoming increasingly clear that now he is starting to pay a high price for this confidence. His clear mastery of the text has few equals, his silvery sound emanation, melodious legato and elegant phrasing certainly captivate, but, like the river Leta, they can sometimes lull to oblivion … “

In a word, Pollini, like others, is not at all sinless. But like any great artist, he feels his “weak points”, his art changes with time. The direction of this development is also evidenced by the review of the mentioned B. Morrison to one of the artist’s London concerts, where Schubert’s sonatas were played: I am glad to report, therefore, that this evening all reservations disappeared as if by magic, and the listeners were carried away by music that sounded as if it had just been created by the assembly of the gods on Mount Olympus.

There is no doubt that the creative potential of Maurizio Pollini has not been fully exhausted. The key to this is not only his self-criticism, but, perhaps, to an even greater extent, his active life position. Unlike most of his colleagues, he does not hide his political views, participates in public life, seeing in art one of the forms of this life, one of the means for changing society. Pollini regularly performs not only in the major halls of the world, but also in factories and factories in Italy, where ordinary workers listen to him. Together with them, he fights against social injustice and terrorism, fascism and militarism, while using the opportunities that the position of an artist with a worldwide reputation opens up for him. In the early 70s, he caused a real storm of indignation among the reactionaries when, during his concerts, he appealed to the audience with an appeal to fight against American aggression in Vietnam. “This event,” as the critic L. Pestalozza noted, “turned over the long-rooted idea of the role of music and those who make it.” They tried to obstruct him, they banned him from playing in Milan, they poured mud on him in the press. But the truth won out.

Maurizio Pollini seeks inspiration on the way to listeners; he sees the meaning and content of his activity in democracy. And this fertilizes his art with new juices. “For me, great music is always revolutionary,” he says. And his art is democratic in its essence – it is not for nothing that he is not afraid to offer a working audience a program composed of Beethoven’s last sonatas, and plays them in such a way that inexperienced listeners listen to this music with bated breath. “It seems to me very important to expand the audience of concerts, to attract more people to music. And I think that an artist can support this trend… Addressing a new circle of listeners, I would like to play programs in which contemporary music comes first, or at least is presented as fully as; and music of the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries. I know it sounds ridiculous when a pianist who devotes himself mainly to great classical and romantic music says something like that. But I believe that our path lies in this direction.”

Grigoriev L., Platek Ya., 1990