List |

lat. relatio non harmonica, French fausse relation, germ. Questand

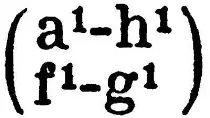

The contradiction between the sound of a natural step and its chromatic-alternative modification in a different voice (or in a different octave). In the diatonic P. harmony system usually gives the impression of a false sound (non harmonica) – as in the direct. neighborhood, and through a passing sound or chord:

Therefore, P. is prohibited by the rules of harmony. A combination of a natural degree with its alteration is not a P., provided that voice leading is smooth, for example:

P. is allowed in harmony D after the second low degree, as well as through a caesura (see examples above, col. 244).

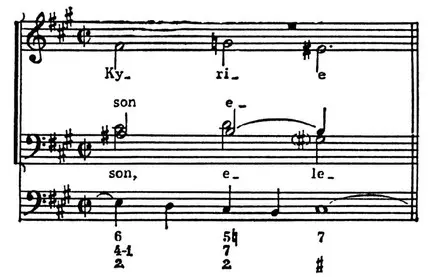

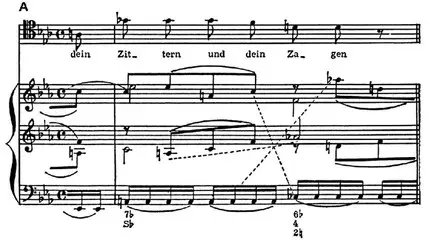

The avoidance of P. is already typical of strict-style counterpoint (15th-16th centuries). In the Baroque era (17th – 1st half of the 18th centuries), singing was occasionally allowed – either as an inconspicuous side effect in conditions of developed voice leading (J. S. Bach, Brandenburg Concerto 1, part 2, bars 9 -10), or as a special. technique for expressing k.-l. special effects, eg. to depict grief or a painful condition (P. a1 – as2 in example A,

J. S. Bach. Mass in h minor, No 3, bar 9.

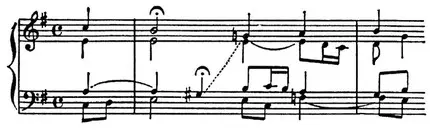

J. S. Bach. Chorale “Singt dem Herrn ein neues Lied”, bars 8-10.

below, is associated with the expression of the word Zagen – longing). In the era of romanticism and in modern. P.’s music is often used as one of the characteristic ladoharmonics. system of means (in particular, under the influence of special modes; for example: P. e – es1 in Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, number 123, bar 5 – based on the everyday mode). P. in example B (embodies the intoxicating charms of Kashcheevna) is explained by the connection with the non-diatonic. low end

J. S. Bach. Matthew Passion, No 26, bar 26.

N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov. “Kashchei the Immortal”, scene II, bars 28-29.

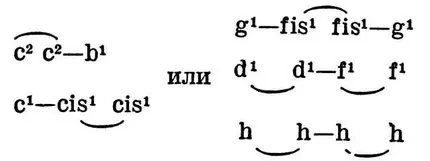

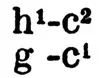

system and its characteristic tone-semitone scale. In the music of the 20th century widely used (by A. N. Cherepnin, B. Bartok, etc.) the two-terts major-minor chord (such as: e1-g1-c2-es2), the specificity of which is P. (e1-es2), as well as related chords to him (see the example at the top of column 245).

I. F. Stravinsky. “Sacred spring”.

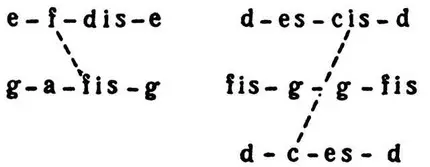

Typical for modern In music, the mixing of modes leads to polyscale and polytonality, where P. (in succession and simultaneity) become a normative feature of the modal structure:

I. F. Stravinsky. Pieces for piano “Five fingers”. Lento, bars 1-4.

In so-called. atonality enharmonic. the values of the steps are equalized, and P. becomes unrealizable (A. Webern, concerto for 9 instruments, op. 24).

The term “P.” – abbreviation of the expression “non-harmonic P.” (German: unharmonischer Querstand). P. is a part of the group of forbidden discordant successions that has retained its significance, which, in addition to alteration P., also included tritone relations. P. and tritone (diabolus in musica) are similar in that both are outside the limits of thinking based on the system of hexachords (see Solmization), and are subject to the same rule – Mi contra Fa (although not the same):

J. Tsarlino (1558) condemned two b. thirds or m. sixths in a row, since they “are not in a harmonious relationship”; inharmonious the relation is demonstrated by him (in one example) both in P. and in newts:

From G. Zarlino’s treatise “Le istitutioni harmonice” (part III, chapter 30).

M. Mersenne (1636-37), referring to Tsarlino, refers P. to “false relations” (fausses relations) and gives similar examples to the triton and P.

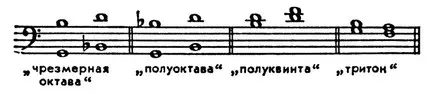

K. Bernhard forbids falsche Relationes: tritones, or “half-quints” (Semidiapente), “excessive” octaves (Octavae Superfluae), “half-octaves” (Semidiapason), “excessive” unison (Unisonus superfluus), giving examples almost literally repeating the above from Carlino.

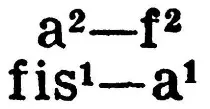

I. Mattheson (1713) characterizes the same intervals in the same terms as “disgusting sounds” (widerwärtige Soni). The entire 9th chapter of the 3rd part of the “Perfect Kapellmeister” dedicated to. “inharmonic P.”. Objecting to certain prohibitions of the old theory as “unjust” (including certain compounds cited by Zarlino), Matteson distinguishes between “unbearable” and “excellent” P. (Dividing “false relations” into “tolerant” and ” intolerant” is also found in S. Brossard’s “Musical Dictionary”, 1703.) X. K. Koch (1802) explains P. as “the succession of two voices, the course of sounds of which belongs to different keys.” Yes, in circulation.

the ear understands the fis-a step in the lower voice as G-dur, the af step in the upper one as C or F-dur. “Relatio non harmonica” and “non-harmonic P.” are explained by Koch as synonyms, and the following

still applies to them.

E. F. Richter (1853) lists “non-harmonic P.” to “non-melodic moves”, but justifies certain “embellishing” (auxiliary) notes or the principle of “reduction” (intermediate link):

Armenian folk love song “Garuna” (“Spring”).

A move that forms an increase. a quart

, Richter relates to P. According to X. Riemann, P. is an allocation of a chromatically changed tone, unpleasant for hearing. Unpleasant in it is insufficient assimilation of harmonics. connections, which can be compared with impure intonation. The most dangerous paradox is when moving towards the triad of the same name; with a tritone step, P. “is downright self-evident” (for example, n II – V); The item at a tertsovy ratio (eg, I — hVI) occupies an intermediate position.

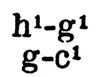

Hess de Calvet (1818) forbids a “non-harmonic move” leading to an open tritone

, however, allows “non-harmonic progressions” if they go “after the intersection” (caesuras). I. K. Gunke (1863) recommends avoiding in a strict style “various relations (Relation) of scales resulting from non-observance of related tones” (an example of P. given by him is a study from b. thirds and from m. sext).

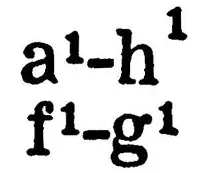

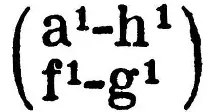

P. I. Tchaikovsky (1872) naz. P. “the contradictory attitude of two voices.” B. L. Yavorsky (1915) interprets P. as a break in the connection between conjugate sounds: P. – “consecutive juxtaposition of conjugate sounds in different octaves and different voices when gravity is performed incorrectly.” Eg. (associated sounds – h1 and c2):

(correct) but not

(P.). According to Yu. N. Tyulin and N. G. Privano (1956), there are two types of P.; in the first, the voices that form the P. are not included in the general modal structure (P. sounds false), in the second, they outline the general modal structure (P. may be acceptable).

References: Hess de Calve, Theory of Music …, part 1, Har., 1818, p. 265-67; Stasov V.V., Letter to Mr. Rostislav about Glinka, “Theatrical and Musical Bulletin”, 1857, October 27, the same in the book: Stasov V.V., Articles on Music, vol. 1, M., 1974, p. 352-57; Gunke I., A complete guide to composing music, St. Petersburg, (1865), p. 41-46, M., 1876, 1909; Tchaikovsky P.I., Guide to the practical study of harmony, M., 1872, the same in the book: Tchaikovsky P.I., Poly. coll. soch., vol. III-a, M., 1957, p. 75-76; Yavorsky B., Exercises in the formation of a modal rhythm, part 1, M., 1915, p. 47; Tyulin Yu. N., Privano N. G., Theoretical Foundations of Harmony, L., 1956, p. 205-10, M., 1965, p. 210-15; Zarlino G., Le institutioni harmonice. A facsimile of the 1558, NY, (1965); Mersenne M., Harmonie universelle. La théorie et la pratique de la musique (P., 1636-37), t. 2, P., 1963, p. 312-14; Brossard S., Dictionaire de musique…, P., 1703; Mattheson J., Das neu-eröffnete Orchestre…, Hamb., 1713, S. 111-12; his, Der vollkommene Capellmeister, Hamb., 1739, S. 288-96, i.e., Kassel – Basel, 1954; Martini G. B., Esemplare o sia saggio fondamentale pratico di contrappunto sopra il canto fermo, pt. 1, Bologna, 1774, p. XIX-XXII; Koch H. Chr., Musikalisches Lexikon, Fr./M., 1802, Hdlb., 1865, S. 712-14; Richter EF, Lehrbuch der Harmonie, Lpz., 1853 Riemann H., Vereinfachte Harmonielehre, L. – NY, (1868) Müller-Blattau J., Die Kompositionslehre Heinrich Schützens in der Passung seines Schülers Christoph Bernhard, Lpz., 154, Kassel ua, 57.

Yu. H. Kholopov